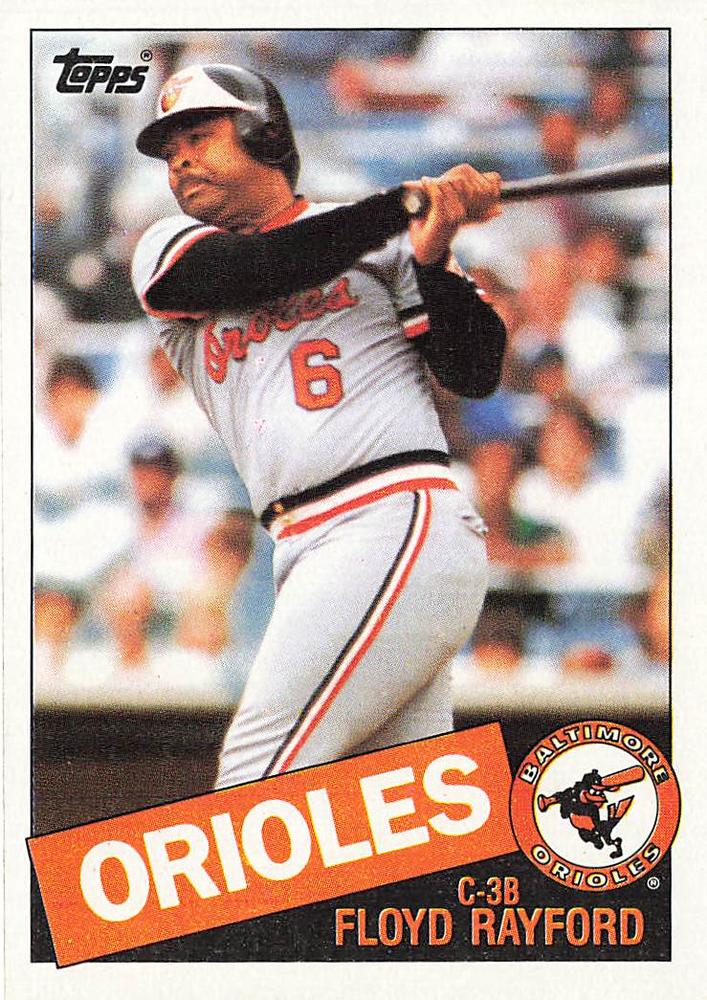

Floyd Rayford

Floyd Rayford’s soft hands and even softer belly, combined with his underrated athleticism and good nature, made him an Orioles’ fan favorite in the 1980s. With the skills to play six positions — primarily third base and catcher — during his professional career, and what one manager called the “perfect temperament for baseball,” Rayford spent nearly four decades in the game as a player, coach or manager.

Floyd Rayford’s soft hands and even softer belly, combined with his underrated athleticism and good nature, made him an Orioles’ fan favorite in the 1980s. With the skills to play six positions — primarily third base and catcher — during his professional career, and what one manager called the “perfect temperament for baseball,” Rayford spent nearly four decades in the game as a player, coach or manager.

Floyd Kinnard Rayford was born in Memphis, Tennessee, on July 27, 1957. His parents, Floyd Rayford and the former Fannie Mae Brown, had met across the Mississippi River in her home state of Arkansas. She was one of nine daughters, and potential suitors had to whistle from the woods outside her fiercely protective father’s home and hope that he wouldn’t hear them and respond with a shotgun blast. Attempting to marry one of the girls was even riskier, but Rayford’s intrepid father succeeded.

When baby Floyd was about eight weeks old, the couple moved him and his half-brother Dwayne 1,800 miles west and settled in South Central Los Angeles. There, his father worked as a carpenter, while the boys were “raised by a mother who cooked mounds of fried chicken, pork chops, pot roasts and barbeque.”1

They grew up seven miles south of Dodger Stadium, Floyd enjoyed the home team’s rivalry with the San Francisco Giants but rooted for Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine and a certain Pittsburgh Pirate. “I idolized Roberto Clemente and liked the way he played,” he recalled.2

Floyd was eight when his old-school dad told him, “I’m going to make a baseball player out of you because you’re too damn lazy to do anything else.” As it happened, the youngster would be over 50 before working his first non-baseball job. His father loved the game, hanging around L.A.’s booming high school baseball scene, and helping coach a Babe Ruth League team that at times included future big leaguers Dan Ford and Chet Lemon.

At 16 young Floyd earned all-Southern League honors as a .444-hitting second baseman at Manual Arts High School, the alma mater of Orioles center fielder Paul Blair. As a junior, he switched to catching and made second-team All-City by batting .465 in 1974. In his 1975 senior season, he captained a squad that came within one game of playing for the city championship at Dodger Stadium. He hit .535, received first-team All-City recognition and was named the Southern League MVP.3 “I had one of the greatest high school careers a human being could have,” he remarked.

That June, the California Angels drafted him in the fourth round, leading to a memorable meeting with the club’s Director of Scouting, Walter Shannon. “It was intimidating. He’s saying, ‘I signed Bob Gibson’ and all these other players,” Rayford recalled. When Shannon underwhelmed him with a $12,500 offer, though, he quickly declined. He planned to attend the University of Southern California instead. When the Angels doubled their offer to $25,000, however, he decided to turn pro. Before making it official on June 24, Shannon ‘treated’ the 17-year-old and his parents to lunch by bringing them something from an Anaheim Stadium concession stand. “He wasn’t going to [actually] pay for lunch,” Rayford explained

Rayford reported to Idaho Falls, where he was the youngest position player on the Angels’ Rookie-level Pioneer League affiliate. He played third base and batted .283 with a team-leading 43 RBIs and 12 doubles in 72 games. He even swiped two dozen bases for an aggressive club that attempted nearly three steals per game.

When he moved up to full-season, Single-A ball in 1976, he hit .273 for the Salinas Angels as they romped to a California League-best 91-49 record. The circuit’s statisticians voted him the best third baseman and his manager, Del Crandall, raved, “Rayford is a tremendous athlete.”4

In 1977, however, Rayford alarmed club officials by reporting to spring training 10 pounds overweight. “Last winter I would go over to my girlfriend’s house a lot and I guess I went to the fridge too often,” he explained.5 When, instead of losing the extra pounds, he proceeded to add 10 more to his listed 5-foot-9, 190-pound frame, the Angels sent him back to Salinas. His average slipped to .259, but six homers and 39 RBIs in 51 games demonstrated that he was developing power. He advanced to the Double-A El Paso Diablos when the Texas League club suffered a rash of injuries but left his car and most of his clothes behind, figuring he wouldn’t stay long.

Shortly after arriving, Rayford homered in a three-hit performance against the Angels in an exhibition.6 Before June was over, he’d enjoyed a 6-RBI outburst7, a four-hit game8 and established himself as a crowd favorite. The El Paso PA announcer enjoyed using nicknames to introduce the players and began calling him “Honey Bear”.9 Others called him “Sugar Bear”, insisting that he resembled the character on the Super Sugar Crisp cereal box.

With “Meat Man” — future batting champion Carney Lansford — a fixture at third, Rayford played all four infield positions, mostly first and second base. “It’s great to have a guy like Floyd on the club,” said manager Buck Rodgers. “I wouldn’t be afraid to play him any place.” Rayford, however, longed for a stable position. “Next year I hope to be just a second baseman. I want to drop 25 pounds and become a power-hitting guy, like Joe Morgan.”10

The Angels added him to their 40-man roster and sent him to play second for the Tomateros de Culiacan, the Mexican Pacific League’s pennant winners that winter. “It was a great experience,” he recalled. “I totally enjoyed it. I benefitted from playing against older players.” For two months, Frank Robinson managed the club, and the 42-year-old clobbered what may have been his final professional homer pinch-hitting for Rayford.11

In 1978, Rayford returned to third base and El Paso and enjoyed a fantastic season. His .313 batting average, 36 doubles and 242 total bases endured as the best marks of his career. After the Diablos notched the league’s best record again, he played for the Tigres del Licey in the Dominican Republic.

He moved up to the Triple-A Salt Lake City Gulls in 1979 but was traded with cash to the Baltimore Orioles for outfielder Larry Harlow in early June. Rayford remained with the Gulls on loan and played in the club’s first 132 games before suffering a leg injury. The local media voted him Gulls’ MVP after a season in which he led Pacific Coast League third basemen in fielding and batted .294 with 13 homers and 80 RBIs.12 He missed the playoffs, and a September call up to the Orioles, but healed in time to play winter ball for the Criollos de Caguas in Puerto Rico.

When Rayford was traded, an unnamed Angels’ official described him as “in a word, fat.”13 Teammates and coaches alike teased him during his first Orioles’ spring training in 1980. “Only one player per uniform!” said Jim Palmer. Frank Robinson hollered, “Rayford, come back!” when the Goodyear Blimp flew over Pompano Beach.14 Spectators could be even less kind. “When I hear fans yelling stuff about my weight, I just think a thousand other people wish they could be out here where I am,” Rayford said.15

Baltimore’s manager was unfazed. “I don’t think he’s big. I think he looks good,” insisted Earl Weaver. “If he was catching every day, everyone would say, ‘He’s built just like Roy] Campanella and (Yogi) Berra’.”16

“Floyd is just naturally big, and there’s nothing you can do about it,” observed Elrod Hendricks, the Orioles’ coach and former catcher tasked with reacquainting Rayford with his former high school position.17

Rayford made Baltimore’s Opening Day roster and debuted on April 17, batting seventh and playing third base at Memorial Stadium. He went 0-for-3 but handled both of his fielding chances. Ten days later in Kansas City, he beat out a bunt single against southpaw Paul Splittorff for his first hit.18 He never caught an inning for the Orioles in 1980, though. After appearing in eight games, he was sent down to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. The emergence of powerful left-handed-hitting Dan Graham to share catching duties with Rick Dempsey caused Weaver to scrap the idea of carrying a third catcher.

At Rochester, Rayford batted only .230 but played five positions, mostly the hot corner. “Rayford is said to be giving the Red Wings their best defensive third base play in five years,” raved one report.19 He rejoined the Orioles in September but appeared only once after they were mathematically eliminated. He married his high school girlfriend, Nancy Hawkins, after the season.

In 1981, Rayford appeared on his first Topps baseball card, an Orioles Future Stars issue alongside Mike Boddicker and Mark Corey. While the other two joined Baltimore in September, he wasn’t recalled after batting .248 with 11 homers at Rochester. That season, he was almost demoted to Double-A, requested a trade and was nearly dealt to the Braves.20 In 1982, Weaver said, “We were hiding Rayford last year so we wouldn’t lose him in the draft.”21

Rayford made history in the wee hours of April 19, 1981. He was catching at 4:09 a.m. when the infamous 33-inning Rochester-Pawtucket marathon was suspended after 32 frames. After entering as a pinch-runner in the 18th, he went hitless as the designated hitter until Red Wings skipper Doc Edwards told him Dave Huppert had had enough after catching the first 29. “Hup had enough 18 innings ago!” Rayford replied.

While Rayford caught more games that year than in his first six seasons combined, he mostly played third base, spelling Cal Ripken, Jr. As the 20-year-old Ripken neared his major league debut that August, Rayford pitched to him for up to two hours each day. “Cal complained that Doc Edwards, who threw batting practice, was too slow,” Rayford explained, quipping, “Cal had a great year, thanks to me.”22

In spring training 1982, Weaver remarked, “Rayford can play. Nobody knows it, but he can play.”23 He made the team and spent all but 10 days of the season in the majors with Ripken as his road roommate. “Every morning, when he woke up, Cal wanted to wrestle and throw you around the room,” he recalled.24 Convinced that Ripken was involved with locking him in the bathroom in Texas, causing Rayford to miss the team bus, he exacted revenge. “During a game in Detroit, I snuck in the clubhouse and cut every button off his shirt,” he confessed.25

Rayford batted only four times in the first 44 games. When he started the second game of a May 29 doubleheader at third base, however, he became the last player to keep Ripken out of Baltimore’s starting lineup until September 20, 1998 –more than 16 years later. When Ripken shifted to shortstop on July 1, Rayford briefly became the starter at third. He hit his first major-league home run two nights later, a two-run, opposite-field shot off Aurelio Lopez at Tiger Stadium. “The Orioles gave him such an effective silent treatment that Rayford bought it,” Tom Boswell described. “Eventually, players started pretending to faint while others tried to revive them with towels. Finally, everybody engulfed Rayford and pummeled him affectionately.”26 His second round-tripper came 48 hours later in Anaheim, but he pulled a hamstring after eight starts and lost the job while he recuperated.

When he was sent back to Rochester in 1983, Rayford wondered if it was time to change careers. “My wife just got into real estate and maybe she could have shown me something,” he said.27 After he pounded Triple-A pitching for a .371 average in 42 games, however, the reigning champion Cardinals acquired him for a player to be named later on June 14. “They were really honest with me,” he said. “I was just there because Lonnie [Smith] had gone on the DL, and they said they didn’t know what to do with me after that.”28

Rayford remained with St. Louis for the rest of the season. On a visit to his hometown in mid-July, he looked out the windows of the team bus as it rolled from the hotel to the ballpark, reminiscing about the streets he’d grown up on. Determined to make his first visit to Dodger Stadium as a major leaguer memorable, he blasted a long, three-run homer off southpaw Jerry Reuss in the first inning that evening. The following night in San Francisco, he whacked a game-winning, pinch-hit home run in the ninth, but he only produced a .212 average in 104 at-bats overall.

That winter, he became an unlikely hero for Licey in the Dominican League playoffs. Manager Manny Mota benched him for the decisive game of the finals for arriving at the ballpark a little tipsy. “I didn’t sober up until the seventh inning,” Rayford admitted. In the ninth, however, he blasted a Cecilio Guante fastball nearly out of the stadium for a pennant-winning homer.

As Rayford exited the ballpark, a man holding a chicken approached him, said something in Spanish and sliced the fowl’s throat. Unsettled and wondering what had happened, it was explained to Rayford that the man had put a hex on him. He was warned “something’s going to happen” should he ever return to the island. Though he didn’t fully believe it, whenever he returned to the country on subsequent cruises, he remained on the ship every time.

Four days before the 1984 season opener, he was sold back to Baltimore. He made his first major league start at catcher on April 20. Within two weeks, Tom Boswell reported that teammates had dubbed him “Rayfanella,” an homage to Roy Campanella.29 Veteran Joe Nolan soon required knee surgery, so Rayford backed up Rick Dempsey for the rest of the year. “I liked catching best,” Rayford reflected. “I was too busy back there to be nervous.”30

At the beginning of the season, Rayford lived with teammate Eddie Murray,31 a fellow L.A. native and former Little League opponent.32 He appeared in 86 games, notched four hits twice in one June week, and cut down 35 percent of opposing base stealers. Though he’d previously played parts of two seasons with Baltimore, the Oriole Advocates named him the Most Outstanding New Oriole.33 “Some guys just have a perfect temperament for the game,” remarked skipper Joe Altobelli. “Rayford’s one of them.”34

At the time Altobelli was fired in June 1985, Rayford had batted only 32 times in Baltimore’s first 55 games. Things changed after Earl Weaver came out of retirement to take over. When American League ERA-leader Dave Stieb of the Blue Jays faced Baltimore on July 30, Weaver started Rayford and told him he’d remain in the lineup all year if he hit safely. “It was a little looper over the second baseman’s head,” he recalled. “If I hadn’t got that hit, he wouldn’t have played me.”35

After the All-Star break, he started all but four games, mostly at third. “Brooks Robinson says Rayford is the O’s best defensive third baseman,” Peter Gammons reported.36 At the plate, Rayford notched a personal best four RBIs in a four-hit performance on June 29, and legged out his only career triple on August 30. He enjoyed a breakout year, batting .306 with 18 homers in 359 at bats after getting divorced at mid-season. “Alimony can be a tremendous motivator,” he joked.37

He soon married again, to the former Susan Sohn and she gave birth to their daughter, Christina, in 1986. Rayford didn’t work out at all that off-season but reported to spring training with a sizeable raise to $310,00038 and a probable starting job. Ten days before Opening Day, however, he chipped a bone in his left thumb and began the season on the disabled list. After only a few games of rehab, he rushed back and tied a league record by committing four errors at third base the night he returned. When his batting average dipped to a sickly .154 in mid-June, the Orioles sent him back to Triple-A.

A few weeks later, Rayford came back up and homered in his second game, but was demoted again after going 2-for-22. He walloped six homers following a September recall but finished the year hitting a disappointing .176. Though the Orioles had updated his weight to 220 pounds in their 1986 media guide, he’d reportedly swelled up to 244.39 The team sent him to a weight loss and nutrition program before deciding whether or not to guarantee his contract for 1987.40

Rayford spent $4,300 of his own money for a two-week program at the Pritikin Center where he learned about healthier eating habits. “No matter what happens to me now, I’m a better person,” he said.41 Baltimore GM Hank Peters told The Sporting News he was encouraged when a slimmed-down Rayford moved within 10 pounds of his 210-pound target weight by January. “With Floyd, losing the weight is just part of it,” Peters said. “Then he has to keep it off and prove that 1985 wasn’t a fluke.”42

The Orioles re-signed him after slashing his salary by the maximum 20-percent, but his opportunities to play were reduced even more.43 Baltimore had acquired three-time All-Star catcher Terry Kennedy in an October trade, and inked third baseman Ray Knight to a free agent deal in February. Rayford made the team but appeared in only five games before returning to Rochester. He hit his way back to the majors by slugging .518 in 48 games there but received only 50 AL at-bats all year and hit .220. The Orioles released him after the season.

In 1988 the White Sox invited Rayford to spring training. Chicago GM Larry Himes had been his first minor league skipper after scouting him in high school. The Sox wanted insurance as they tried to convert outfielder Kenny Williams to third base.44 Williams convinced the Sox he could man the position, however, and Rayford –nursing a shoulder injury– was released again. In 390 games over seven major league seasons, he batted .244 with 38 home runs. The Orioles brought him back as a temporary bullpen coach for a few days in May, but Rayford did not play pro ball for the first time in 14 years. 45

He spent 1989 in a reserve role with the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Red Barons, the Phillies’ Triple-A affiliate, before catching for the Senior Professional Baseball Association’s St. Lucie Legends that fall. In 1990, he became the Red Barons’ hitting coach, and appeared in two dozen contests over the next two seasons to surpass 1,000 minor league games in his career.

For the next two decades, Rayford worked with Single-A prospects. “Baseball is the biggest mind game ever. You have to make people believe that they can do things they don’t believe they can do,” he explained. After the Batavia Clippers’ hitters that he coached led the New York-Pennsylvania League in scoring twice between 1992 and 1995, Rayford managed the club to a 42-33 record in ’96 without a single future big leaguer on the roster. He finished his nine years in the Phillies’ system as a Piedmont Boll Weevils coach in 1997.

After one year in both the Brewers (1998 Beloit Snappers) and Orioles (1999 Frederick Keys) organizations, Rayford commenced a 12-year run with the Minnesota Twins. After four years with the Quad Cities River Bandits, he spent 2004 with the Fort Myers Miracle, then five years with the New Britain Rock Cats. He finished his baseball career in a familiar place in 2010 and 2011, with the Rochester Red Wings, where he’d played parts of seven seasons.

Rayford divorced again in the new millennium. After his daughter earned her master’s degree, he moved from Maryland to Gainesville, Florida, where he married French-Canadian Sue Holland in 2012. She handles the budget for the Tacachale Center, Florida’s oldest community for mentally challenged adults.

After Rayford’s weight soared from 215 to 285 in his first year out of baseball, he told his wife he needed something to do. “I’m a terrible golfer,” he joked. In his late 50s, Rayford started the first non-baseball job of his life, working security at the Tacachale Center. In 2020, he proudly reported, “I weigh 191 now. Only six more than I did in high school.”

Looking back, Rayford says just being around Hall of Famers like Eddie Murray, Cal Ripken and Ozzie Smith was his biggest thrill. “Even when I was going bad, the fans treated me good,” Rayford told the Baltimore Sun in 2009. “They liked me. I didn’t have the greatest body type, but I was out there trying to do it.”46

Last revised: December 18, 2020

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Floyd Rayford (telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, August 30, 2020).

This biography was reviewed by Gregory Wolf and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org and the United States Census from 1940.

Notes

1 Richard Justice, “Momma’s Pork Roasts Now Off Limits as Rayford Works Body into Shape,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), March 19, 1987: 3D.

2 Unless otherwise cited, all Floyd Rayford quotes are from a telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, August 28, 2020.

3 “Manual Arts Catcher Named MVP in Southern League,” Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1975: D10.

4 Dick Miller, “Crandall’s Big Gamble Pays Off,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1976: 43.

5 Tom Lindley, “Hungry Rayford is Real Handyman,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1977: 41

6 “Texas League,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977: 46.

7 “Diablos Have 19-1 Cruise,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1977: 44.

8 “Dodgers Win in 17th,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1977: 41.

9 Glen Chern, “Sports Biz,” Prospector (El Paso, Texas), July 14, 1977: 11.

10 Lindley, “Hungry Rayford is Real Handyman.”

11 Jose Carlos Campos, “Frank Robinson, Su Paso Por Culiacan,” https://www.elrinconbeisbolero.com/index.php/columnas-de-opinion/9-jose-carlos-campos/1-frank-robinson-su-paso-por-culiacan (last accessed November 17, 2020).

12 1980 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 140.

13 Dan Shaughnessy, “All Star Voters Doing Their Best to Prove System’s Inequities,” Washington Star, June 10, 1979: 23.

14 Peter Gammons, “Wide Open Races? AL Should Have Two,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1980: 34.

15 Thomas Boswell, “Rayford: Fill-In is Full-Fledged Oriole Now,” Washington Post, May 4, 1984: E1.

16 Ira Winterdam, “Rayford Gives Orioles Heavy Hitting,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, March 31, 1986: 4D.

17 Ken Nigro, “Orioles Beef Up Opinion of Hefty Rookie Rayford,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1980: 46.

18 Dan Shaughnessy, “Weavers New Twist for Yankees,” Washington Star, April 28, 1980: D3.

19 Merrell Whittlesey, “DeCinces May Need Back Surgery,” Washington Star, August 29, 1980: 15.

20 Ken Nigro, “Birds Give ‘Fats’ Rayford Another Shot,” Baltimore Sun, February 25, 1982: B1

21 Jack Mann, “Rayford Makes Do Playing a Waiting Game,” Washington Times, June 18, 1982.

22 Mike Klingaman, “Catching Up With…Former Oriole Floyd Rayford,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 2009: D2.

23 Ken Nigro, “Orioles Hill Staff is Question Mark,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1982: 20.

24 Klingaman, “Catching Up With…Former Oriole Floyd Rayford.”

25 Klingaman, “Catching Up With…Former Oriole Floyd Rayford.”

26 Boswell, “Rayford: Fill-In is Full-Fledged Oriole Now.”

27 Rick Hummel, “Rayford Supplies Heavy Hitting,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1983: 14.

28 Hummel, “Rayford Supplies Heavy Hitting.”

29 Boswell, “Rayford: Fill-In is Full-Fledged Oriole Now.”

30 Klingaman, “Catching Up With…Former Oriole Floyd Rayford.”

31 Boswell, “Rayford: Fill-In is Full-Fledged Oriole Now.”

32 Dan Shaughnessy, “Orioles Put Baseball in Motion for 1980,” Washington Star, February 26, 1980: 15.

33 1985 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 168.

34 Boswell, “Rayford: Fill-In is Full-Fledged Oriole Now.”

35 “Floyd Rayford Joins Tom Davis and Rick Dempsey on ‘O’s Xtra,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c1QgpLkVeYo (last accessed November 17, 2020).

36 Peter Gammons, “’I’ve Paid My Dues’, Says All Star Carew,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1985: 17.

37 Klingaman, “Catching Up With…Former Oriole Floyd Rayford.”

38 “Notebook A.L. East,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1986: 52.

39 Justice, “Momma’s Pork Roasts Now Off Limits as Rayford Works Body into Shape.”

40 “Orioles,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1986: 52.

41 Justice, “Momma’s Pork Roasts Now Off Limits as Rayford Works Body into Shape.”

42 “A.L. East,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1987:42.

43 Stan Isle, “Rayford Grievance?” The Sporting News, June 1, 1987: 27.

44 Joe Goddard, “Warming to Third Base,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1988: 30.

45 Richard Justice, “Injury Puts Robinson Back in the Hospital,” Washington Post, May 18, 1988: C3.

46 Klingaman, “Catching Up With…Former Oriole Floyd Rayford.”

Full Name

Floyd Kinnard Rayford

Born

July 27, 1957 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.