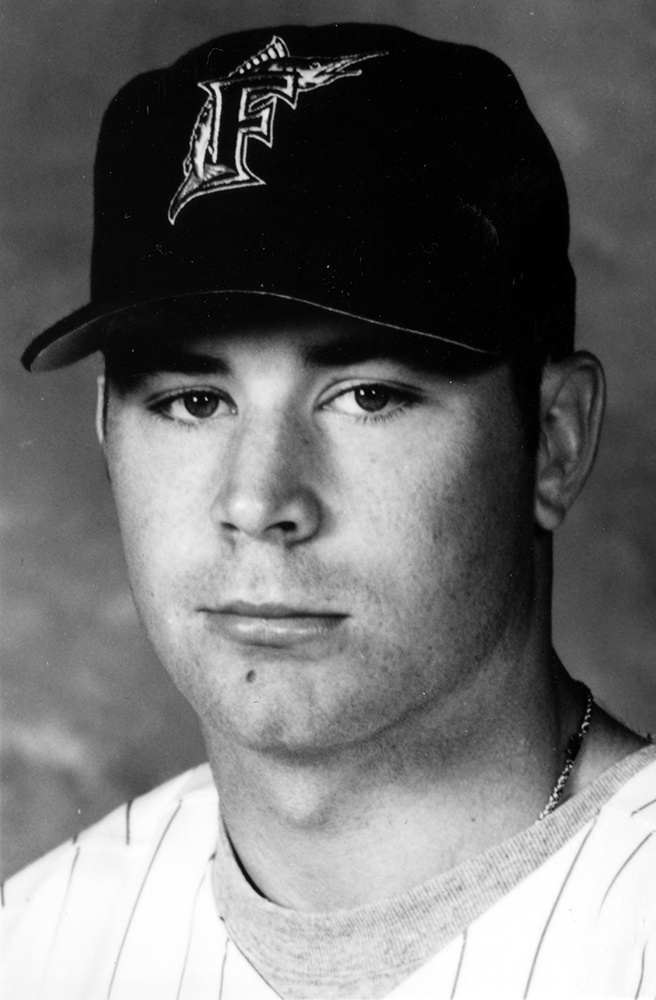

Tony Saunders

On Opening Day 1998 the reigning World Series champion Florida Marlins took the field minus a dozen of their 1997 teammates, many of whom were, as The Sporting News put it, “victims … of a halved payroll,” adding, “The roll call of departed comrades read like a Memorial Day remembrance of war casualties” with the loss of perennial All Stars such as Moises Alou, Kevin Brown, Jeff Conine, and Robb Nen.1 The absent roster also included 23-year-old Tony Saunders who, despite a pedestrian 4-6, 4.61 record in his rookie season, had shown enough promise during the championship run to warrant angst over his loss. “My main concern is pitching,” Marlins skipper Jim Leyland said going into the 1998 campaign. “Losing Brown, Nen, and Saunders, that’s frustrating.”2

Marlins pitching coach Larry Rothschild was no less impressed by the left-handed hurler. The first manager of the expansion Tampa Bay Devil Rays, Rothschild played a key role in the Devil Rays’ selection of Saunders as the first player chosen in the 1997 major-league expansion draft. A seemingly bright future loomed for the youngster before a gruesome injury in 1999 ended his career.

Anthony Scott Saunders was born in Baltimore on April 29, 1974, the younger of two sons of William Frederick Saunders III and Joan (Lewis) Saunders. His paternal grandparents were from New England and William Frederick Jr. appears to have preceded his son in pursuit of a military career. Tony’s father was born in Ohio in 1945 but settled in Maryland in the 1970s. Tony went to school in the Baltimore suburbs, attending Howard High School in Ellicott City before transferring to Glen Burnie High for his senior year. (His parents divorced when he was a child and one report suggests the transfer occurred because Tony moved from his mother’s home into his father’s.) Though he played baseball in the backyard of the Baltimore Orioles, Saunders grew up admiring Atlanta Braves lefty Tom Glavine and patterned his pitching style after the future Hall of Famer, focusing on control and change of speed.3 After graduating from high school in 1992 the All-County hurler spurned an athletic scholarship at George Mason University in Northern Virginia to pursue a professional career. Bypassed in the major-league amateur draft, Saunders attended an open tryout, where he was signed to a $1,000 bonus contract by Marlins scout Ty Brown.4

Saunders was assigned to Florida’s Gulf Coast (Rookie) League team. Used exclusively in relief, the 18-year-old surrendered just 29 hits in 45⅔ innings while placing among the league leaders with 24 appearances in the short 60-game season. In 1993 Saunders was promoted to the Kane County (Illinois) Cougars in the Midwest League (Class A), where he continued his excellence with a record of 6-1, 2.27 in 23 appearances (10 starts). Elbow surgery limited him to just 23 starts (131 innings) over the next two seasons before Saunders rebounded with a record of 13-4, 2.63 in 1996 to pace the Portland (Maine) Sea Dogs to a first-place finish in the Double-A Eastern League. He led the league with 156 strikeouts while placing among the leaders in wins, starts (26), and innings (167⅔). The Marlins selected Saunders among the September call-ups though he did not make an appearance. Tabbed as the franchise’s minor-league pitcher of the year, Saunders was sent to the Arizona Fall League, where his performance earned praise from Marlins GM Dave Dombrowski.

Except for the superb pitching of All-Stars Kevin Brown and Al Leiter, the Marlins’ rotation was at best spotty and Saunders, who was added to the 40-man roster during the offseason, was eyed as a strong candidate to fill the club’s fourth or fifth starter role. In his first spring-training start Saunders cemented his standing by striking out four over three shutout innings without a ball reaching the outfield en route to a strong Grapefruit League campaign. “He showed what he’s shown every time we’ve seen him,” Rothschild said. “He had a very, very good changeup, and he hit spots in and out with his fastball. He has good-enough command to go after people in tough spots.”5

On April 5, 1997, Saunders made his major-league debut in Florida’s Pro Player Stadium against the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds threatened in the first and scored in the second before Saunders settled down to retire the next 16 batters in a row. Lifted in the seventh after yielding a run-scoring double, Saunders did not figure in the decision in a 4-3 extra-inning win. Two weeks later, in San Francisco, he held the Giants to three hits with 10 strikeouts over 7⅓ innings (including striking out the side in the fourth) before a pair of eighth-inning singles led to a 3-2 Marlins loss (the tying and winning runs scored on a two-out double off relief pitcher Rick Helling).

Saunders struggled in two subsequent starts, yielding 12 runs (nine earned) over seven innings though he did not figure in either decision. On May 8 he bounced back against the defending NL champion Braves with six scoreless innings to earn his first major-league win (helping his own cause with a third-inning leadoff homer against Glavine for the game’s first tally). Five days later he beat the Braves again after yielding only five hits and three runs over seven innings. On May 18 Saunders was lifted after carrying a 2-1 lead over the Pittsburgh Pirates through five innings. A double-play groundball from Pirates first baseman Kevin Young would prove to be Saunders last major-league pitch in nearly two months when a sprained right knee landed him on the disabled list.

After a minor-league rehab assignment Saunders returned to the Marlins in July stronger than ever – a 1.85 ERA over four starts. But he was 0-2 over this period as the Marlins managed just one run in three of the four games. On July 31 Saunders faced off against his favorite patsies, the Braves, to earn his third major-league win, all against Atlanta, as he combined with three relievers in a 1-0 nailbiter. Around this time the Marlins optioned Luis Castillo as the future All-Star second baseman struggled through an injury-plagued first half. Immersed in a three-way pennant race with the Braves and New York Mets, the Marlins dangled Saunders before the Philadelphia Phillies in an unsuccessful attempt to acquire second sacker Mickey Morandini.

But far less success awaited Saunders in the closing months of the 1997 season. Excluding a September 17 win against the Philadelphia Phillies – his last victory in the National League, he finished with a record of 0-3, 8.23 over nine appearances (eight starts). Saunders was unable to reach the third inning in two starts and, after watching videotape of one of these dismal appearances, he admitted, “That was the first time I’ve watched myself pitch (on tape), and I just look lethargic, like I was waiting for something [bad] to happen.”6 He finished the season with a record of 4-6, 4.61 in 111⅓ innings. Though Saunders placed among the club leaders with 102 strikeouts, this was countered by 64 walks. Control issues would plague him throughout his short career.

On September 23 the Marlins clinched the NL wild card – the franchise’s first-ever postseason berth – with a 6-3 win over the Montreal Expos. Marlins manager Leyland planned a different rotation for each possible West Division foe and when that turned out to be the Giants, Leyland, who wanted two left-handed starters against a left-handed-leaning San Francisco lineup, announced his choice of Saunders over fellow rookie Livan Hernandez in the series. “This is a … surprise,” Saunders confessed. “I didn’t even think I would be on the roster in the first round [of the playoffs]. I thought they might put me on the roster if we played Atlanta. I haven’t been pitching that well lately, and Livan has been pitching great.”7 As it turned out, the Marlins swept the best-of-five series and Saunders didn’t pitch.

The club did not find it quite as easy against the Braves in the NLCS. On October 10 Saunders took the mound in Game Three with the series locked up at one game apiece. He and future HOF righty John Smoltz dueled to a 1-1 tie through five innings before Saunders was lifted in the sixth. The Marlins scored four runs in their half of the frame for a 5-2 win (Hernandez got the victory) and advanced to the World Series after capturing Games Five and Six.

Leyland reshuffled his rotation for the World Series against the Cleveland Indians by selecting Saunders and Hernandez as starters. (Eighteen years passed before another team – the 2015 Mets – used two rookie starters in the fall classic.) Tabbed as the starter in Game Four in Cleveland, Saunders said, ““I’m very excited. … This is something you never really think about because you don’t believe it’s going to happen your first year. There’s a lot of players who play a long time and never get the opportunity (to play in the World Series), and I’m getting it my first year.” Seemingly needing to defend his selection in the pressure-packed situation, Leyland said, “[Saunders is] on his way to becoming a very fine pitcher. I’m sure he’ll have jitters; I’d worry if he didn’t.”8

The Indians countered with their own rookie starter, Jaret Wright, who had faced off against Saunders less than a year earlier in the Arizona Fall League. The Series “was a juxtaposition with respect to the weather. Four of the games were held in sunny, hot Miami, Florida, while the three others were held in freezing Cleveland, Ohio. Naturally, the games in Cleveland were going to be very cold, but no one expected” Game Four temperatures of 38 degrees. “[A]s the game progressed into the later innings, the media reported wind-chill readings as low as 18°F [to mark] the coldest game in fall classic history.”9 The frigid temperatures affected Saunders as he surrendered three runs in the first inning and another three in the third en route to a 10-3 Marlins loss. It proved to be the last postseason appearance of his career.

In what many considered a surprise move, the Marlins did not protect Saunders in the 1997 expansion draft. Meanwhile, the emphasis the Devil Rays placed on pitching was evident by the selection of nine consecutive hurlers in the middle rounds. But no one was more important to the new club than number-one selection Tony Saunders. Along with free agents Wilson Alvarez, Roberto Hernandez, and Dave Eiland, the left-handed hurler was looked upon to stabilize the staff in the club’s inaugural season. On April 2, 1998, the franchise’s third game, Saunders took the mound against the Detroit Tigers in Tropicana Field. He surrendered a game-opening homer to outfielder Brian Hunter before settling down to hold the Tigers to four hits and no runs through the sixth. Saunders was lifted in the seventh and did not figure in the decision in the 7-1 Devil Rays win.

As once-promising 1962 Mets hurlers Al Jackson and Jay Hook might have advised more than a generation beforehand, pitching for an expansion club was fraught with its own set of challenges. By July 4 the 20 losses Saunders and Devil Rays righty Dennis Springer compiled equaled that of the entire New York Yankees staff. After an April 16 win against the Anaheim Angels, Saunders compiled a major-league-high 16 starts without a win. Except for a particularly dreadful June in which he surrendered 24 runs in 29⅓ innings, many of the losses pinned on Saunders resulted from a lack of run support. In 15 of his 31 appearances he delivered a 2.59 ERA (league average: 4.65) that yielded eight losses and seven no-decisions. Throughout this dismal run, the 24-year-old remained remarkably stoic. “[The coaches have] been telling me … to stay with it, that things will turn around, that your luck will change,” said an optimistic Saunders.10 Control remained a problem as he surrendered a major-league-leading 111 walks while his seven hit batters contributed to the Devil Rays’ 81 HBP (a mark that approached the record 85 by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1895). Three days after the season ended, Saunders had arthroscopic surgery to remove a small bone chip from his left elbow. Throughout the offseason the Devil Rays fielded trade inquiries for the promising lefty but all offers were turned away. “[T]he team expects him to be part of the rotation for many years,” Marc Topkin wrote in The Sporting News.11

But a spotty start in 1999 forced Topkin to admit that “Saunders continues to be equal parts astounding and confounding.”12 On April 22 the lefty’s wildness – seven walks and a HBP – left hitters flat-footed as Saunders held the Orioles hitless through 7⅔ innings in a 1-0 win. But this near-gem – the closest he ever came to a major-league shutout – was sandwiched between four starts in which Saunders yielded 25 earned runs over 14⅓ innings. Briefly optioned to the Durham Bulls, he returned to the Devil Rays on May 15 and surrendered just three hits and one unearned run to beat the Angels in what proved to be his last major-league win.

Eleven days later, on May 26, Saunders appeared equally as strong against the Texas Rangers before a leadoff homer in the third was followed by three singles. Protecting a two-out, 3-2 lead he uncorked a full-count wild pitch to reigning AL MVP Juan Gonzalez that allowed the tying run to score. But little attention was paid to the tally as the focus of players and fans alike turned to the screaming pitcher writhing on the ground. The loud popping sound heard by all present was the breaking of Saunders’ humerus, the long bone in the upper arm located between the elbow joint and shoulder. “You could hear it, plain as day,” said teammate Wade Boggs, who was in the Devil Rays dugout. “That’s about as bad as it gets.” “Obviously, you’re shocked,” said Rothschld, who had rushed onto the field with the club’s trainer and medical personnel after Saunders hit the ground. “[A break like this is] very rare.”13

Rare perhaps, but hardly unheard of, because Saunders joined a list of four pitchers, all lefties, who had sustained similar injuries in the preceding 10 years (from Dave Dravecky in 1989 to Norm Charlton, Tom Browning, and John Smiley in the 1990s). Only Charlton – Saunders’ teammate – was able to sustain a measure of success thereafter. Lying in a bed in St. Petersburg’s Bayfront Medical Center that evening, Saunders vowed to break this trend. Six months later, after surgery to remove scar tissue from his left elbow (a procedure unrelated to the break) he announced his goal of being ready by Opening Day 2000. Though Jamie Reed, the Devil Rays trainer, felt the projected goal unrealistic, he worked closely with Saunders on a strenuous rehab program.

Saunders’ goal was indeed overoptimistic: In July 2000 he threw 73 pitches with good velocity (approximately 85 mph) in the first of two simulated games. A month later he took the mound for the Charleston (South Carolina) River Dogs in the South Atlantic League, where he surrendered one hit and struck out two over two innings (27 pitches). Projected to join the Devil Rays in September, Saunders was moved to the St. Petersburg Devil Rays (Advanced Class A), where the parent team could closely monitor his progress. But all of his hard work went for naught on August 24 when Saunders suffered a second broken humerus in a game against the Clearwater Phillies. The break occurred just above the first, and this time Saunders knew it was the end. In a tearful press conference two days later the 26-year-old announced his retirement.14 “I’d give anything if I could get back out there and play again,” he said later. “You don’t know how bad I want to say, ‘You know what? Maybe I could try again.’ But then reality sets in. And common sense sets in. There ain’t no way I can go through that again.”15

In the fall a panel of representatives from the office of the commissioner, the league offices, and Boston media selected Saunders as one of two recipients of the 2000 Tony Conigliaro Award. Named after the Boston Red Sox outfielder who returned to baseball in 1967 following a severe head injury only to succumb to cancer 23 years later, Saunders was recognized for his valiant attempt to overcome his ghastly injury. Shortly thereafter, the Devil Rays established the Tony Saunders Courage Award to recognize high-school athletes in the Tampa-St. Petersburg region who overcame adversity.

In November 2000 Saunders joined the Devil Rays front office as an assistant for scouting and player development. Seeking to become a GM, he eventually resigned the job after tiring of writing reports on minor-league players whom he had once played alongside. Saunders dabbled in a number of ventures that included memorabilia sales, a partnership in a restaurant-bar near Tropicana Field called Bermuda Jake’s, and a short stint as a broker with Morgan Stanley. Unable to stay away from baseball, in 2004 Saunders began coaching an AAU team in Tampa and discovered he could throw pain-free. The Devil Rays agreed to release him so he could solicit interest from other clubs. The Dodgers were interested, but on January 19, 2005, Saunders was signed by Orioles scout Ty Brown (the scout who originally signed him for the Marlins in 1992). Joining the Orioles in spring training as a nonroster invitee, Saunders was assigned to the Bowie (Maryland) Baysox in the Double-A Eastern League, but he never made an appearance. He briefly surfaced with the Mesa (Arizona) Miners in the independent Golden Baseball League before retiring for good.

In 2005 Saunders’ former Devil Rays teammate José Canseco released his tell-all exposé on Major League players’ steroid use entitled Juiced: Wild times, Rampant ’Roids, Smash Hits and How Baseball Got Big. In the book the slugger-turned-author claimed that Saunders’ broken arm was likely the result of steroid abuse. The allegation sparked a public war of words as Saunders vehemently denied the claim. Emphasizing that he and Canseco were far from friends, he said, “If I don’t have that injury, I’m nowhere near that book. He used my injury as a punch line. … Baseball was my livelihood. … It ain’t right.”16

Saunders moved back to Maryland, where the appeal of baseball remained strong. He was a pitching coach for a baseball school in Glen Burnie and on June 20, 2010, he traveled to Cooperstown, New York, to pitch one inning in the Hall of Fame Classic. Four years later he launched a short-lived business advisory venture called Strike 3 Consulting, LLC. On June 16, 2016, Saunders married Christine Jennings in the Annapolis suburb of Arnold, Maryland. It was his second marriage – 21 years earlier he had married his high-school sweetheart, Joyce Dickerson. That union produced a daughter, Samantha, and a son, Anthony, before dissolving in divorce around 2010.

Saunders’ passion for baseball is represented by the tattoo on his left shoulder that says, “My World,” the words written in script above a hand holding a baseball. His fervor for the sport is represented throughout his career from his valiant attempt to come back from a devastating injury to his vehement denial when he was accused of using steroids. Initially overlooked by major-league scouts in the 1992 amateur draft, Saunders fought his way through the minors to establish himself as one of the most promising pitchers during the last years of the twentieth century.

Last revised: January 5, 2017

This biography appears in “Overcoming Adversity: The Tony Conigliaro Award” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Clayton Trutor.

Sources

The author wishes to thank Dean Giampola and SABR members Bill Mortell and Rod Nelson (chair of the SABR Scouts Committee) for their valuable research.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Breaking Up,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1998: 42.

2 “Diaspora in South Florida,” The Sporting News, January 5, 1998: 63.

3 In 1997 Saunders’ first major-league win came at the expense of his idol.

4 Ty was the son of Pittsburgh Pirates executive Joe L. Brown, grandson of the comedian Joe E. Brown.

5 “Nen, Club Succumb to Giants’ Hitting,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1997: 22.

6 “It’s All in the Family for Talented Alous,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1997: 43.

7 “Playoff Rotation Set to Combat Lefties,” The Sporting News, October 6, 1997: 44.

8 Steve Eby, “Eighteen Crazy Nights – Looking Back at the 1997 Cleveland Indians,” October 22, 2014. Accessed September 3, 2016. (bit.ly/2bLzn1O).

9 Matt Nadel, “The Coldest Game in World Series History,” January 5, 2014. Accessed September 3, 2016. (bit.ly/2bTkDsf ).

10 “Saunders Pitches Past His Early Problems,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1998: 27.

11 “Expansion Picks Provide Solid Footing for Future,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1998: 68.

12 “Saunders Continues to Astound and Confound,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1999: 22.

13 “Saunders Breaks Arm While Pitching,” May 27, 1999. Accessed September 4, 2016. (bit.ly/2cbz0vO).

14 “The Tampa Bay Devil Rays, Then and Now,” April 24, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2016. (bit.ly/2cqlIvB).

15 “Career-ending Injury Puts Devil Rays Lefty in Front Office,” The Sporting News, December 4, 2000: 63.

16 “Tony Saunders Denies Steroid Allegations,” February 21, 2005. Accessed September 4, 2016. (bit.ly/2bOUpg2).

Full Name

Anthony Scott Saunders

Born

April 29, 1974 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.