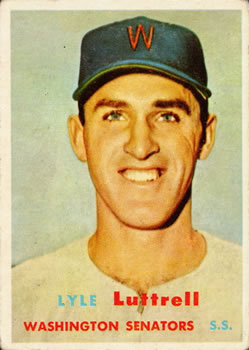

Lyle Luttrell

“We have a prize shortstop coming,” Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith exclaimed in November 1953. “His name is Lyle Luttrell . . . He played a year for us in Orlando and I expect him to be playing for us by opening day next spring.”1 A sportswriter said the 23-year-old was “the talk of scouts who watched him perform at shortstop.”2

“We have a prize shortstop coming,” Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith exclaimed in November 1953. “His name is Lyle Luttrell . . . He played a year for us in Orlando and I expect him to be playing for us by opening day next spring.”1 A sportswriter said the 23-year-old was “the talk of scouts who watched him perform at shortstop.”2

All the bright projections aside, on Opening Day 1954, Luttrell was toiling in Class-A Charlotte following a difficult spring training. The youngster did not make his major-league debut until two years later, and he continued to struggle. Luttrell made just 57 big league appearances over the two-year 1956-57 span and was out of baseball altogether by 1960. Another of the multitude of players who felt the sunshine on his face but briefly, Luttrell, if he’s recalled at all, is best remembered in the law books: the first player to successfully sue an opponent for damages caused from injuries sustained during an on-field fight.

Lyle Kenneth Luttrell was born on February 22, 1930, the second of three sons of James Kenneth and Ada Loretta (Starnes) Luttrell in Bloomington, IL, 130 miles southwest of Chicago. He was the seventh great-grandson of County Meath, Ireland natives James and Susannah (Tullos) Luttrell (possibly Loterill). In the 1680s this pair had arrived in Northumberland County, Virginia, 100 miles southeast of present day Washington, D.C. where the Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay. Around 1800 James’s great-grandson, Joshua Luttrell, moved inland to northern Kentucky, a westward drift that culminated in the family settling in the Midwest shortly after the Civil War. Through the 1920s many of the male descendants made their living underground in the coal mines in Pike County, IN. Lyle’s father was among the first to break this trend. In the mid-1920s, about the time he married Ada, James Luttrell found work as a foreman for a wholesale dry goods distributor. The couple eventually moved to 200 miles northwest to Bloomington, close where Ada had grown up.

In 1948 Lyle, who had shown a propensity toward athletics from an early age, entered Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington where he teamed with future major-league backstop Cal Neeman. Three years later he attended the Jack Rossiter Baseball School in Cocoa, FL. Rossiter, a longtime Senators scout had established the training camp in the 1930s and sent more than 400 ballplayers into Organized Baseball during the school’s extended tenure. One of 19 students who signed with the Senators in February 1951, Lyle Luttrell took up his first assignment just 40 miles west with the Class-D Orlando Senators in the Florida State League. In the light-hitting circuit (league average: .261) the fleet-footed infielder batted .267 in 562 at-bats while placing among the leaders with eight triples. With “agility, a fine arm and steadiness” Luttrell was tabbed for quick advancement.3

Luttrell’s immediate future did not include a rapid promotion. Called to active duty by the US Navy during the Korean War, the youngster spent the next two years in Florida at the Jacksonville Naval Air Station. Garnering flattering reviews for his play on the station’s baseball teams, when Luttrell received his service discharge in December 1953 many observers expected him to jump straight to the majors.

Entering the 1954 season with veteran Pete Runnels, the Senators were not lacking a shortstop. But what the future two-time AL batting champion brought to the team offensively was offset by his spotty defense; in each of the preceding three seasons Runnels placed among the AL leaders in errors. Management hoped the slick-fielding Luttrell would allow them to bump Runnels to second base to replace light-hitting Wayne Terwilliger. These plans went awry when Luttrell, following a difficult spring training, was assigned to the Charlotte Hornets in the South Atlantic League. He rebounded quickly, hitting above .300 in the first weeks of the season. But on May 16, Luttrell injured his wrist sliding, and he played through the pain for several days before going on to the DL. Returning in June, the wrist appears to have affected Luttrell’s hitting as he fell into an extended slump throughout the second half of the season. Despite his offensive difficulties he still made the circuit’s All Star team. When the Senators committed to moving Runnels to second during the offseason, The Sporting News contributor Shirley Povich projected Luttrell, whom he referred to as the club’s future “fielding flash,” as “among the top candidates for the shortstop job.”4

Povich’s use of the plural was significant. In the spring of 1955 no fewer than five players were competing for the Senator’s starting job at shortstop. Days before the start of the season, following another lousy training camp, Luttrell was optioned to the AA Chattanooga Lookouts in the Southern Association (the Senators’ highest minor league affiliate). Then he got injured again on May 14, when a fastball from Little Rock flamethrower Gene Host broke his jaw and sidelined him for four weeks. Once back in the lineup, Luttrell mounted a steady comeback. In the closing weeks, he was the Lookouts hottest hitter, striking at a .418 clip with a 13-game hitting streak in August. But his season abruptly halted on August 20 when, after dodging three brushback pitches from Nashville righthander Jerry Lane, Luttrell took a shot to the midsection. Angrily throwing his bat toward the pitcher, Luttrell “was facing the mound . . . when [Nashville catcher [Earl] Averill swung into action,” The Sporting News reported. “[He] looped [a] punch over the shortstop’s right shoulder and dropped [Luttrell] to the ground unconscious.”5 The impact of the fall refractured the earlier injury, and Luttrell was rushed to Chattanooga’s Physicians and Surgeons Hospital where his jaw was wired back into place. Within days he brought a $50,000 suit for actual and punitive damages against Averill, who had been “jailed on an assault and battery charge following the incident,” and the Nashville Volunteers.6 The suit would not be resolved for more than a year. Meanwhile, despite the considerable time he had lost, Luttrell still finished among the Lookout’s leaders in hits (107), doubles (19), triples (6), and total bases (150).

The lack of lofty projections in the spring of 1956 appears to have benefitted Luttrell. No longer under the glare of constant attention, he produced a strong grapefruit league campaign that put pressure on slick-fielding but light-hitting sophomore shortstop Jose Valdivielso. Among the club’s last cuts, Luttrell lost the competition and was reassigned to Chattanooga. Perhaps especially motivated, he lashed out at a league leading .397 average (39-for-103) through the first month of the season, a brilliant pace that included his hitting safely in 19 of 20 games. Meanwhile Valdivielso struggled at the plate (.150 through May 5), prompting the Senators to quickly recall Luttrell. On May 15, he made his major-league debut in Chicago’s Comiskey Park as the visitor’s starting shortstop. Taking the collar against White Sox righthander Bob Keegan, the normally surehanded fielder’s jitters were apparent when he committed a fifth inning throwing error that contributed to two unearned runs in the Senators 5-1 loss. Following an unsuccessful pinch-hit appearance three days later, Luttrell returned to the lineup on May 29 against the Baltimore Orioles. In the fifth inning, he got his first major-league hit, a leadoff triple to centerfield against Erv Palica, and scored on a single by catcher Lou Berberet. Two innings later Luttrell stroked a leadoff single to center and came around to score a second run in the Senators 6-5 win.

Nats manager Chuck Dressen kept Luttrell in the starting lineup, and the youngster responded with six hits in 15 at-bats over the next four games. On May 31, he got his first major-league home run leading off the seventh inning in Yankee Stadium against New York righty Don Larsen. The Yankees vehemently disputed the call, claiming that the ball had “bounced off the chest of right fielder Joe Collins into the stands and should have been called a ground-rule double instead. [After consulting with Collins] umpire Bill Summers” stood by the original call.7 The next day Luttrell hit a clean fifth inning leadoff double against future Hall of Famer Bob Lemon and helped fuel a 5-3 comeback win over the Indians. Toting a .286 average through June 5, many thought the kid was finally living up to the soaring expectations once ascribed to him.

But then Luttrell plunged into a 2-for-24 slump, and after a June 13 appearance against the Kansas City Athletics he was returned to Chattanooga. His batting stroke returned with hit streaks of 10 and 15 games, and Luttrell finished the season among the league leaders with nine triples and a .324 average in 460 at-bats. Selected among the September call-ups, he was inserted into the starting lineup with the big club over the season’s last 17 games. Though Luttrell struggled with six errors and only seven hits in 53 at-bats, the Senators, with their eyes on his All-Star season in Chattanooga, more or less expected him to capture the starting job at shortstop in 1957. “Luttrell isn’t loose when he gets his major-league trials,” Dressen explained. “He’s nervous and over-eager and that works against him. He’s got everything to be a big leaguer, including range at shortstop.”8

In November 1956, the Hamilton County, Tennessee, Circuit Court heard the case Luttrell brought against Averill and the Nashville Volunteers. Averill interrupted playing winter ball in the Mexican Coast League and returned stateside to testify. A dozen witnesses, including Lookouts manager Cal Ermer and other teammates, sportswriters, and two doctors testified on his behalf. On November 23 a jury awarded Luttrell $5,000 in compensatory damages, but a state appeals court overturned the verdict on the grounds that the Nashville club was not responsible for Averill’s actions since he “had not acted within the scope of his employment when he struck Luttrell.” Though Luttrell collected no money, predictions that the verdict “would have a far-reaching effect on Organized Ball” proved correct when the Chicago Cubs, whose lawyers cited the Luttrell case, and pitcher Jim Brewer brought a $1,040,000 suit against Cincinnati Reds second baseman Billy Martin in 1960 following a similar on-field incident.9

In 1957, Dressen appointed himself Luttrell’s personal batting tutor during spring training. The lessons appeared to take when the shortstop hit .379 with seven extra base hits in spring play. The offensive surge attracted interest from the Philadelphia Phillies, but Dressen would not consider parting with his prized pupil. But when the regular season started, Luttrell’s bat took a vacation and he struggled to maintain an average above the Mendoza line. On May 16, in what proved to be his last major-league appearance, he struck out against White Sox lefty Billy Pierce as a ninth inning pinch-hitter. Four days later the Senators selected veteran Cincinnati shortstop Rocky Bridges off the waiver wire and assigned Luttrell to the Seattle Rainiers in the Pacific Coast League (the Redlegs Triple-A affiliate with whom the Senators had a working relationship). Languishing behind Brooklyn prospect Maury Wills—the Dodgers had the same working relationship with Seattle—Luttrell played just 45 games at shortstop (most of which came in July when Wills was sidelined with a back injury) and made 22 additional appearances at second, third, and as a pinch-hitter. When the season ended, he retired—maybe.

Sometime between 1949-53 Luttrell had moved to southern California with his parents. During the 1957-58 offseason, he went to work with the Los Angeles police department before being lured back into baseball. Added to the Senators 40-man roster, Luttrell was promptly assigned to Chattanooga where he spent most his time in a third base platoon with future Hall of Famer Harmon Killebrew. On May 29, the Lookouts traded Luttrell to the team he had taken to court a year earlier—the Nashville Volunteers—for NL veteran third baseman Tommy Brown. Two weeks later he quit baseball once again and returned to his Los Angeles home. The Vols released Luttrell in May 1959 after he’d spent some time on their inactive list. Coaxed out of retirement once again, this time by the Class-A Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists in the South Atlantic League, he made 42 appearances into July, and then he finally quit Organized Baseball for good.

During his time with the Lookouts Luttrell met and eventually married Tennessee native Margie Margurete Taylor. After his playing career Luttrell settled in Chattanooga. The union produced five children and remained intact until his premature death. On July 11, 1984, five months after his 54th birthday, Luttrell died of a heart attack in Chattanooga. He was buried in the Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Luttrell’s big league career was much shorter than scouts first projected when they saw the youngster perform in the early 1950s. He got 32 hits, two homers, and 14 RBIs over a two-year span with the Senators. As it turned out, Luttrell had better luck in the courtroom than the diamond.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com. The author wishes to thank SABR member Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Notes

1 “Vernon, Yost Untouchables on Nat Roster, Griffith Says,” Ibid., November 18: 17.

2 “Runnels Skid Big Whodunit to Nat Brass,” The Sporting News, November 4, 1953: 7.

3 “Low Man at Start, Luttrell Now Tops Nats’ Line at Short,” Ibid., April 17, 1957: 14.

4 “Dressen’s First Job for Nats—Talk ‘Ol Case Out of Catcher,” Ibid., November 3, 1954: 18.

5 “Averill, Jr., Sued After He Breaks Jaw of Luttrell,” Ibid., August 31, 1955: 31.

6 “Obituaries: Lyle K. Luttrell,” Ibid., July 30, 1984: 48.

7 “Collins Backs Ump vs. Mates,” Ibid., June 13, 1956: 26.

8 “Senators Lineup to Test Skill of Chuck—Shuffleboard Expert,” Ibid., February 27, 1957: 26.

9 “$5,000 Verdict for Luttrell in Suit Based on Field Fight,” Ibid., December 5, 1956: 24. The Billy Martin case ultimately ended in a judgment on January 29, 1969—almost nine years after the incident—of $22,000 for Brewer ($10,000 for the injury plus court costs). Oddly enough, Martin had not inflicted serious injury on Brewer. A teammate had. Peter Golenbock, Wild, High, and Tight: The Life and Death of Billy Martin (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), 137-38.

Full Name

Lyle Kenneth Luttrell

Born

February 22, 1930 at Bloomington, IL (USA)

Died

July 11, 1984 at Chattanooga, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.