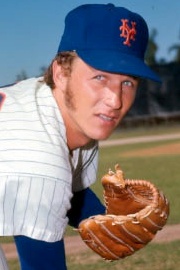

Tommy Moore

Tommy Moore was drafted as an outfielder but made it to the majors as a pitcher. He appeared with four teams in parts of four seasons from 1972 through 1977, posting a won-lost record of 2-4 and an ERA of 5.40 in 42 games, largely in relief. “He would have been a great candidate for a cut fastball instead of that big curveball he had trouble controlling,” said outfielder Mike Floyd, who played against Moore in the minors and in the Mexican winter league.1

Tommy Moore was drafted as an outfielder but made it to the majors as a pitcher. He appeared with four teams in parts of four seasons from 1972 through 1977, posting a won-lost record of 2-4 and an ERA of 5.40 in 42 games, largely in relief. “He would have been a great candidate for a cut fastball instead of that big curveball he had trouble controlling,” said outfielder Mike Floyd, who played against Moore in the minors and in the Mexican winter league.1

Moore also made an impression with his lively, irreverent personality. “We gravitated together because we were both so cocky,” Floyd remembered. Another friend, Lou Cafiero, added, “He had strong opinions and was very candid — not afraid to say ‘F*** ’em’ if it was called for.”2 Cafiero also noted that Moore enjoyed coining ribald nicknames for certain teammates.3

Tommy Joe Moore was born on July 7, 1948, in Lynwood, California (in Los Angeles County, just north of Compton). The Moore family had come to California from various parts of the southern and western United States. Tommy’s father, George Arthur “Doc” Moore, was a welder. The Moores were originally from Cornwall, England, but went to Tennessee and Texas. His mother, Frances (née Luksich), was born to a Croatian father and Austrian mother. Her family grew up in New Mexico and Colorado. She stayed at home with Tommy, his older brothers George and Travis, and his younger brother Jerry.4

Moore grew up in Norwalk, California, about 10 miles east of Lynwood, and went to John Glenn High School in Norwalk. As is true of so many big-leaguers, he was an outstanding all-around athlete. The 1973 yearbook of the New York Mets, his first organization, said that he capped a remarkable scholastic athletic career by captaining the baseball, football, and basketball teams as a senior.

The Minnesota Twins selected Moore in the 28th round of the June 1966 draft. He chose not to sign, going instead to Cerritos College (also in Norwalk). He was there just several months, because the Mets chose him in the 10th round of the secondary phase of the January 1967 draft. The scout who landed Moore was Nelson Burbrink, whose main credit was Tom Seaver.

The US was fighting the Vietnam War then, but Moore was never called into military service. It’s quite likely that his draft status was 3-A, because he was already married and a father in 1967. With his first wife, Tina, he had two children named Joie and Tommy Jr. He was then married to Pam, with whom he had two sons named Brandon and Adam. His third marriage was to a woman named Gayle; they had no children. Finally, he married his first wife’s sister, Sharon, whom he had known since high school.5

Moore signed with Mets in May 1967 after batting .305 for Cerritos as a freshman.6 His pro baseball career began that June with Marion (Virginia) of the Appalachian League (rookie ball). He hit .290 with 3 homers and 28 RBIs in 59 games. He also showed good speed, stealing 11 bases — and in particular, arm strength, with a league-leading 14 assists.7

Moore moved up to Visalia in the California League (Class A) in 1968. After putting up a line of .240-6-41 with 15 steals, he spent a second year at Visalia. Playing right field, he hit much better in 1969 (.285-16-85 in 117 games) and lifted his stolen-base total to 23. In the field, he racked up 28 assists, one short of the league record.8 In a sign of things to come, he also pitched a 1-2-3 inning in relief.9

A beaning that summer heralded Moore’s conversion. Chuck Estrada, who was on deck, described what happened. (So far it has not been possible to pinpoint the date and the opposing pitcher.) The ball came in high and tight, and Moore froze, as Estrada demonstrated with a wide-eyed, open-mouthed expression. It caught Moore smack in the mouth and teeth flew all over the place. Estrada said, “Tommy, understandably, became somewhat gun-shy. It wasn’t the first time he’d been beaned.”10

When that ball knocked his teeth out, Moore had to get dentures. His niece, Niki Moore Hatzenbuehler, remembered, “He would always pull them out and make silly faces — he even did this at my dad’s funeral just to get me to smile.” She also described how when she was an innocent little girl, her uncle pulled her leg. He told her that the cartoon “Tom and Jerry” was written after him and her father because they were so famous and that all of their fights and adventures had to be recorded to make other people laugh. “I truly believed him for several years,” she said.11

To start the 1970 season, Moore was assigned to Memphis in the Texas League (Class AA). He got into just nine games, however, and wasn’t happy about warming the bench. Thus, in June the organization decided to put him on the mound.12 He was a little on the short side for a pitcher at 5-feet-11, but “that arm was too good to waste,” said Mike Floyd.13

The change came from Whitey Herzog, who was then the Mets’ director of player development.14 Moore later said, “I always had a lot of faith in Whitey — he’s a guy who knows talent and has a knack of bringing out the best in young players.” In the wake of Moore’s broken jaw and lost teeth, Herzog also cited concern about bailing out at the plate.15

Stepping back to Pompano Beach in the Florida State League (Class A), Moore pitched in 16 games, starting 13 and going 3-8 with a 3.62 ERA and 63 strikeouts in 82 innings. He also appeared in six games in the outfield, his last there as a pro. At his new position, he showed a great curveball.16 On August 8, he took a no-hitter into the eighth inning against Miami, ultimately losing, 2-1.17 Despite 51 walks, his overall showing merited promotion to Tidewater on August 17.18 He got into four games with the Tides over the rest of the season, striking out 11 and walking 10 in 12 innings.

Moore proved that he was a legitimate pitching prospect that winter in the Florida Instructional League (FIL). He led the circuit with a 1.00 ERA in 54 innings pitched; his record was 6-2.19 “He’s a natural,” said Chuck Estrada, who’d become minor-league pitching coach for the Mets. “All I’ve done with Tommy is taught him to relax.”20

Moore’s FIL performance prompted the Mets to place him on their 40-man roster so he would not be lost to another team. It also won him an invitation to spring training with the big club in 1971. The odds against winning a job were long, however, because the Mets were rich in pitching then. Just two jobs were open on the 10-man staff, and he was competing against eight other hurlers. As Mets beat writer Jack Lang put it, “kids like Charlie Williams, Jesse Hudson, Jim Bibby, Rich Folkers, Tommy Moore and Bill Denehy. . .would have to be awfully, awfully good to make it, and chances of them being given that opportunity is [sic] very slim.”21

Nonetheless, Moore underscored his promise after moving up to Class AA. Back with Memphis, he struck out a league-leading 160 batters in 191 innings, quite a good ratio then. His control also improved (just 64 walks). As a result, he was 11-10 with a 3.20 ERA, helped by four shutouts. The high point was a seven-inning no-hitter in the second game of a doubleheader against Arkansas. He knew he had the no-no going all the way, noting that he had his stuff and that everything was really working. In the crowd was Mets farm director Joe McDonald, who told Moore, “You’re on your way and I’m behind you.”22

A little over a month later, Texas League president Bobby Bragan named Moore to the All-Star team that faced the San Diego Padres at Albuquerque on August 9.23 He was the second of four pitchers, giving up a run in two innings and getting no decision as the Padres won, 4-3.24

Moore pitched for the Culiacán Tomateros in the Mexican Pacific League in the winter of 1971-72. He was named as a strong candidate to make the Mets staff in 1972, since the team had traded away Nolan Ryan.25 He did not do so that spring, as Buzz Capra won a job instead. However, Moore moved up to Tidewater for 1972, and he continued to pitch well: 11-5, 2.80 with three shutouts. Two of them were one-hitters: against Peninsula on July 7 and against Syracuse on August 1. Then, on August 6, versus Rochester, he threw his second no-hitter. All three of these gems were also seven-inning affairs as part of twin bills. Moore called the no-hitter a bigger thrill than the one from 1971 because he was a step closer to the big leagues and it was a lot tougher than Double-A ball.26

When rosters expanded that September, Moore made it to the majors for the first time. He made his debut on September 15 at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. Gary Gentry was shelled for six runs in two-plus innings; after Ron Santo singled to follow a Jim Hickman grand slam, Moore entered. He struck out Rick Monday, and Santo was caught stealing to make it a double play. Glenn Beckert then flied out. Moore pitched a 1-2-3 fourth inning but left after giving up three runs in the fifth.

Moore pitched two scoreless innings at Shea Stadium on September 19. His last outing of the year came in the nightcap of a doubleheader at Montreal’s Jarry Park on October 2. Another twin bill was scheduled for the following day, as the Mets and Expos made up games that had been postponed in April (a frequent occurrence at Jarry). Thus, the bigger rosters came in handy.

Moore and Carl Morton had a mound duel, each pitching seven scoreless innings. Moore helped himself to a 1-0 lead in the eighth, singling with two outs and taking second on an error by shortstop Tim Foli, then scoring on Wayne Garrett’s single. The Expos tied it up in their half of the inning, however, as Moore allowed two singles and fireman Tug McGraw couldn’t get him out of the jam. The Mets then won it in the ninth.

During the offseason, Mets general manager Bob Scheffing said that the team viewed both Moore and Hank Webb as fine prospects, and that they would get good shots at starting in 1973.27 Shortly thereafter, manager Yogi Berra seconded Scheffing, saying, “I like Moore. He’s got a good curve and he’s a bulldog.”28

At the same time, Berra suggested that Jerry Koosman could go to the bullpen, but the veteran lefty remained in the rotation in 1973. Harry Parker also forced his way into the picture with a good spring.29 Moore began the season with Tidewater again, as did Webb and Capra.

Webb was the first of the three to be recalled, in late April, as the Mets optioned outfielder Rich Chiles. On May 10, however, New York sent Webb down and called Moore up.30 After not being used for 12 days, he had two scoreless relief outings of an inning apiece.

Then, on May 28 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, he got another start. It didn’t go well. Bobby Bonds, known for hitting leadoff homers, took Moore deep on the first pitch.31 The Giants then knocked him out of the box in the second inning.

Moore appeared in one other game as a Met, as a pinch-runner on June 3. He then went back to Tidewater, and the Mets recalled Capra. Moore pitched respectably for the Tides (9-11, 3.15 in 22 games, all starts). However, he was not called up amid the exciting pennant race that September.

Again Moore was odd man out in spring training 1974; this time Bob Apodaca got the nod. At Tidewater once again, Moore posted another good ERA: 3.22 in 162 innings across 26 starts, with three shutouts. One of his teammates that year, Benny Ayala (a good friend from prior spring training camps), reiterated, “He had a great overhand curveball.”32 Yet offensive support was lacking, because his record was 7-12. Worsened control (103 walks, or nearly 6 per 9 innings) was also a factor; Moore said a lot of the trouble was mental.33 The Mets did not call him up during the 1974 season.

On October 13, 1974, New York Mets sent pitcher Ray Sadecki along with Moore to the St. Louis Cardinals for Joe Torre, whom they had coveted for several years. Cardinals beat writer Neal Russo remarked that Moore was still regarded as a good prospect but was out of options.34

For the second straight offseason, Moore chopped firewood, joining a brother and their friend in that business in Texas.35 He also pitched briefly that winter in Venezuela. He got into one game for Tiburones de La Guaira, pitching a scoreless inning and getting a save.

Moore looked good for St. Louis in Florida in the spring of 1975. For the first time, he made an Opening Day roster.36 Manager Red Schoendienst pointed out that Moore’s slider was looking better than his curve, and his change-up improved thanks to pitching coach Barney Schultz.37 Moore got into 10 games out of the bullpen for the Cardinals in April and May, giving up eight earned runs in 18 2/3 innings (3.86 ERA) while getting no decisions.

On June 4, 1975, the Cardinals traded Moore with Ed Brinkman to the Texas Rangers for Willie Davis. Texas assigned Moore to Spokane in the Pacific Coast League (PCL) but called him up in early July. Over the remainder of the season, he was a seldom-used reliever, going 0-2, 8.14 in 12 games. Manager Frank Lucchesi did also call on Moore twice as a pinch-runner, which was something Moore had volunteered to do before Billy Martin was fired as skipper. Moore’s speed helped the tying run to score in the 13th inning of a 9-8 Rangers win on July 23.38 On the mound, he allowed only one unearned run in his first five outings, but an ugly showing at Baltimore on August 15 led Lucchesi not to use him for two weeks. That next opportunity also went poorly, and Moore appeared just once more the rest of the way.

Moore languished at Triple-A again throughout 1976. With Sacramento, the Rangers’ new farm club in the PCL, he was 10-7, 4.65 as a swingman (13 starts in 33 appearances). “People these days would refer to him as edgy,” said Mike Floyd (whose own career had ended after 1975). “You get stuck in the minor leagues for a couple of your good physical years and you start to not give a s***.”39

The Seattle Mariners, one of the two new AL expansion teams, purchased Moore’s contract from the Rangers that October. He returned to Venezuela that winter, rejoining La Guaira for the postseason and throwing 4 1/3 scoreless innings in relief appearances. Again showing a good slider, he then made the Mariners staff in spring training.40

Moore got into 14 games for Seattle in April and May, including the last of his three big-league starts. On April 27 at Metropolitan Stadium in Minneapolis, he pitched four scoreless innings and was staked to a 2-0 lead. But the Twins tied it with runs in the fifth and sixth, and he got the loss after allowing two more in the seventh.

Those several weeks also featured Moore’s two wins in the majors. On April 13 at the Kingdome, he went the last 2 2/3 innings and got the W when the M’s scored a run in the bottom of the 13th..On May 12, again at home, he came on in the second inning in relief of Rick Jones and preserved a 3-2 Seattle lead. He pitched three innings that night as the Mariners went on to beat the Yankees, 8-6.

Moore pitched just once more in the majors, on May 15. As he had in 1975, he walked more than 5 batters per 9 innings, which fueled a 4.91 ERA. He was designated for assignment as Mike Kekich came off the disabled list. Mariners executive Lou Gorman had a spot for him with Toledo of the International League, which was then a Cleveland Indians affiliate. Moore didn’t want to go there but said he would if there were no other alternative.41

“I’ve been optioned by the best and the worst,” Moore said. “I’ll tell you, it’s tough. I’ve been a Triple-A player for a long time, maybe too long.” Yet he remained optimistic, citing the example of a Seattle teammate in exhibition season, reliever Dave Johnson, whom the Twins had acquired and promoted. “Maybe it isn’t a grave I’m being put in,” reasoned Moore. “Dave came back, I won’t give up.”42

Moore wound up in the PCL again, on loan to Spokane, which had become a farm club of the Milwaukee Brewers. He was 4-4 with a lofty 6.72 ERA in 14 starts. After pulling some muscles in his side on July 22, he was written off for the rest of the season on August 15.43

That December, Seattle traded Carlos López and Moore to the Baltimore Orioles for Mike Parrott. The Orioles gave Moore a non-roster invitation to spring training, and the odds against him were very long. There were 21 pitchers in camp, and manager Earl Weaver expected to keep just eight of them during the first month of the regular season.44 Baltimore released Moore in March 1978 after he pitched just two innings and gave up four hits and three runs. He did not go to Triple-A Rochester, as had been expected. Red Wings manager Ken Boyer said, “From his background and what I saw of him in camp, I figured he’d have a tough time.”45

Moore thus retired from baseball at age 29. He didn’t have enough service time in the majors to become vested in Major League Baseball’s pension plan; his career predated 1980, when the requirement was reduced to 43 days but was not made retroactive. Thus, he became one of the hundreds of men who received merely the modest annual payments to non-qualified players of $625 per quarter of service, which took effect in 2011. His views on this topic are not known.

Moore did pitch again in 1989 when the Senior Professional Baseball Association (SPBA) formed. By then 41, he was with the Bradenton Explorers when the season started.46 According to SABR’s 2016 article on the SPBA, he wound up pitching for the St. Lucie Legends, posting a 9.82 ERA in 40 1/3 innings pitched. His 1990 SPBA baseball card shows him back with the Explorers for the league’s curtailed second season (the St. Lucie franchise had folded).

Moore’s niece Niki believed that he also had a desire to coach in the minors or majors. Though that did not come to pass, he regularly attended reunions of the Rangers and kept up with friends and former teammates.47 “Going to those reunions and meeting all of the baseball players growing up was one of the fondest memories I have of my childhood,” said Niki.48

Moore lived in the town of Yucca Valley, on the northern edge of Joshua Tree National Park in southern California. He worked at the nearby Morongo Casino, Resort & Spa as a pit boss.49 When he married Sharon Carter, he became stepfather to her daughters Chere, Christina, and Lila. He said of Sharon, “She’s a Godsend. Between us, we have three boys, four girls and I can’t count the number of grandbabies. We have two great-grandbabies with two on the way.”50

Tommy Moore was diagnosed with lymphoma of the brain in September 2017. He was too weak for chemotherapy or radiation owing to the rapid spread of the cancer and was given three to six months to live. He passed away in his sleep on November 16, 2017.51

“He loved people with all his heart,” said Niki Hatzenbuehler. “If you were ever part of his family, you were always his family. From as early as I can remember, my Uncle Tom loved my brothers and me, just like his own. He would joke and make us laugh and always be silly around us to cheer us up. That’s who he was. He brought laughter wherever he went. He had this incredible gift of making you feel like the most important person on the whole planet when he was around you.”52

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Tommy Moore’s niece, Niki Moore Hatzenbuehler, for her input (e-mail, March 16, 2018).

Continued thanks to Mike Floyd and Benny Ayala for their input. Thanks also to Guillermo Gastélum Duarte (for Moore’s statistics in Mexico), Lou Cafiero, and Eric Pomerance.

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

Facebook.com (personal pages of Tommy Moore and relatives)

Pelotabinaria.com.ve (Venezuelan statistics)

Notes

1 Facebook posts, Mike Floyd, March 1, 2018 (hereafter “Floyd Facebook posts”).

2 Facebook posts, Lou Cafiero, March 1, 2018.

3 E-mail from Lou Cafiero to Rory Costello, March 18, 2018. The nicknames shall not be presented here because of their personal nature.

4 E-mail from Niki Moore Hatzenbuehler to Rory Costello, March 16, 2018 (hereafter Hatzenbuehler e-mail #1). Information on the Luksich family comes from ancestry.com.

5 Hatzenbuehler e-mail #1.

6 “Mets Sign Moore, Cerritos,” Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram, May 20, 1967, 18.

7 Dave Lewis, “Onetime Outfielder Moore Logs Tides’ First No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1972.

8 Ibid.

9 “Moore Converts into Mound Gem,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1971, 44.

10 Jack Ellison, “Mets’ Moore: From Hit-By-Pitch To Hit Pitcher,” St. Petersburg Times, November 24, 1970, 2-C. This game must have been before July 12, the date on which Estrada announced his retirement.

11 Niki Moore Hatzenbuehler, Facebook post, November 17, 2017 (quoted with her permission). Hereafter Hatzenbuehler Facebook post.

12 Ibid.

13 Floyd Facebook posts.

14 Jack Lang, “Rookie Moore Could Win Met Starter Job,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1972, 52.

15 Neal Russo, “Fancy-Firing Bob] Forsch Takes Top Perch on Cardinals’ Hill,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1975, 9.

16 Lang, “Rookie Moore Could Win Met Starter Job.”

17 “Class A Leagues,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1970, 39.

18 “International League.”

19 “Pirate Prospect Rennie]Stennett Grabs FIL Bat Crown,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1971, 61.

20 Ellison, “Mets’ Moore: From Hit-By-Pitch To Hit Pitcher.”

21 Jack Lang, “Mets, Long on Quality, Hang Two ‘Vacancy’ Signs on Hill,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1971, 36/

22 “Moore Converts into Mound Gem.”

23 “Travelers’ Jorge] Roque Tops Texas Stars,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1971, 44. Note that the Texas League and Southern League played together as the Dixie Association in 1971.

24 Carlos Salazar, “Al] Severinsen Is Stopper; Padres Top Texas Stars,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971, 41.

25 Lang, “Rookie Moore Could Win Met Starter Job.”

26 Lewis, “Onetime Outfielder Moore Logs Tides’ First No-Hitter.”

27 Jack Lang, “Mets May Have More Fun Than Work in Hawaii,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1972, 51.

28 Jack Lang, “Danny] Frisella Fire Helmet Goes to Koosman,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1972, 38.

29 Jack Lang, “Parker Adds Up Met Wins by Playing Numbers Game,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1973, 29.

30 “Mets Obtain Tommy Moore,” United Press International, May 11, 1973.

31 Wire service accounts of the game noted the count.

32 E-mail from Benny Ayala to Rory Costello, March 17, 2018.

33 Russo, “Fancy-Firing Forsch Takes Top Perch on Cardinals’ Hill.”

34 Neal Russo, “Bing [Devine Fires Early, Shuffles Torre Off to Mets,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1974, 21.

35 Russo, “Fancy-Firing Forsch Takes Top Perch on Cardinals’ Hill.”

36 Neal Russo, “Devine Cuts Deck of Cards, Finds John] Denny at Top,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1975, 10.

37 Russo, “Fancy-Firing Forsch Takes Top Perch on Cardinals’ Hill.”

38 “Tommy Moore Than a Pitcher,” Marshall (Texas) News Messenger, July 24, 1975, 12.

39 Floyd Facebook posts.

40 Hy Zimmerman, “Husky Hurlers Sparkle for Mariners,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1977, 40.

41 Hy Zimmerman, “Once-Despised Seattle Out Front in Gate Race,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1977, 13.

42 “Moore Will Not Abandon Quest to Play in Majors,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1977, 33.

43 “Coast Toasties,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1977, 38.

44 Greg Boeck, “Upstart Orioles a Year Older, but Better?”, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 26, 1978, 1D.

45 “O’s Release Moore, Denver Ready for A’s,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 23, 1978, 5D.

46 “Baseball’s back: SPBA plays first games today,” Detroit Free Press, November 1, 1989, 55.

47 Hatzenbuehler e-mail #1.

48 Hatzenbuehler Facebook post.

49 Hatzenbuehler e-mail #1.

50 Ibid. Tommy Moore’s Facebook page (unknown date).

51 Hatzenbuehler e-mail #1.

52 Hatzenbuehler Facebook post.

Full Name

Tommy Joe Moore

Born

July 7, 1948 at Lynwood, CA (USA)

Died

November 16, 2017 at Pioneertown, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.