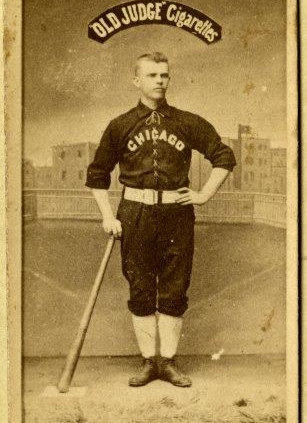

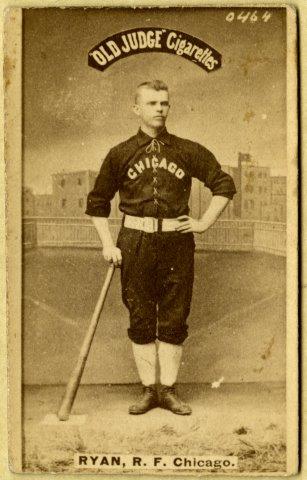

Jimmy Ryan

Jimmy “Pony” Ryan had the batting skill to hit .308 in his 18-year major-league career, the throwing ability to set a National League record for career outfield assists, and a temper that provoked him to punch multiple reporters and a train conductor.

Jimmy “Pony” Ryan had the batting skill to hit .308 in his 18-year major-league career, the throwing ability to set a National League record for career outfield assists, and a temper that provoked him to punch multiple reporters and a train conductor.

James P. Ryan was born on February 11, 1863, in Clinton, Massachusetts, a town in the central part of the state with a population around 3,800 at the time of his birth. Malachi Kittridge, Ryan’s teammate in Chicago from 1890-1897, was also born in Clinton. Additionally, Hall of Famer Billy Hamilton grew up in Clinton at the same time as Ryan.

Ryan’s father Michael was born in 1834 in Ireland and his mother Margaret (McLaughlan) was born in 1840, also in Ireland. Michael worked as a teamster, putting in long hours driving a horse-drawn wagon to make deliveries and loading and unloading the cargo himself. Margaret was a housekeeper. Jimmy was the second-youngest of four children with older twin sisters named Catharine and Margaret, and a younger brother named Francis.1

Ryan attended College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, although it is unclear if he played baseball there.2 He later attended Boston College, where he played baseball and graduated in 1885.3 Ryan’s professional debut came in 1884, when he divided the season between three different minor league clubs – Holyoke of the Massachusetts State Association, and Meriden and New Britain of the Connecticut State League. He stood five-foot-nine, weighed 162 pounds, batted right-handed, and threw left-handed.

In 1885, Ryan was with another minor-league team based in Connecticut, the Bridgeport Giants, when the National League’s Chicago White Stockings signed him and brought him to the majors. His major-league debut was on October 8, 1885, in Chicago’s 5-3 home loss to the Philadelphia Phillies. Ryan played shortstop, batted seventh in the order, and went 1-for-4. The Chicago Tribune said the next day that Ryan “proved himself a strong batter, a quick fielder, and very clever between bases.”4

His major-league debut was not the only time that Ryan lined up as a left-handed shortstop. He played 58 games at short, eight games at second base, and six games at third base in his major-league career. Ryan played outfield in 1,945 of his 2,041 major-league games. He appeared in two more games for the White Stockings before the 1885 season ended and made a great impression, going 6-for-13 at the plate in his first three big league games.

Ryan was one of the first major-league position players that batted right-handed and threw left-handed. A 2009 analysis by The Hardball Times ranked Ryan as the second-best right-hand-hitting/left-hand-throwing position player in MLB history. Only Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson outranked him.5

In 1886, Ryan appeared in 84 White Stockings games and continued hitting well, batting .306 with 27 extra-base hits. The White Stockings returned to the World Series that year and lost to the St. Louis Browns four games to two. Ryan went 5-for-20 in the series and also pitched five innings, allowing five earned runs. His hurling was not limited to the World Series; Ryan pitched in 24 regular season games in his career and posted a 6-1 record with a 3.62 ERA. He led the National League in games finished with five in both 1886 and 1888.

After a solid season in 1887, hitting .285 in 126 games, Ryan had a breakout year in 1888. He led the National League in hits (182), doubles (33), home runs (16), slugging percentage (.515), and total bases (283). On July 28, Ryan hit for the cycle in Chicago’s 21-17 slugfest win at home versus Detroit. He was also the winning pitcher that day, and as of March 2021 he is the only player in major-league history to hit for the cycle and earn a pitching win in the same game.6 After the season, Hall of Fame executive Al Spalding invited Ryan to join a group of other major leaguers on a world tour. The voyage started in St. Paul, Minnesota, and then went west to Los Angeles before moving internationally to Australia, Egypt, England, France, Hawaii (not yet a U.S. state), Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Scotland, and Sri Lanka.7

Ryan led the National League in total bases again in 1889 with 297. He hit a career-high 17 home runs that year, including six homers to lead off games. His six leadoff longballs stayed a single-season record until Bobby Bonds of the San Francisco Giants hit 11 in 1973.8 In 1890, he was one of many star players who left their National League contracts to join the Players League, a major league created by the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players that sought more profits and contractual freedom for players. Ryan signed with the Chicago Pirates, a club that finished fourth and was managed by future Hall of Famer Charles Comiskey. The Players League folded after its only season. While some participating players were inspired by the rebellion against National League owners, Ryan was happy to return to the status quo, saying:

“I’ve had enough of it. There’s more wind than money in it. Let the men who put up the capital manage the game, and let the men who do the playing get paid for it and keep still. This is all any ballplayer should ask. There is one thing certain and that is that I will not play under the same conditions as I did this season.”9

Ryan was back in the National League with the Chicago Colts in 1891, a team that finished in second place and was managed by future Hall of Famer Cap Anson, who was also Ryan’s manager in his rookie season with the White Stockings. On July 1, 1891, Ryan hit for the cycle in Chicago’s 9-3 home win over Cleveland, making him the first player in the history of Chicago’s National League franchise to hit for the cycle twice.

On June 4, 1892, Ryan umpired his first and only major league game. He was hurt and unable to play in Chicago’s 7-3 win in Baltimore that day, and when the scheduled umpire did not show up, Ryan and Orioles manager Ned Hanlon volunteered to officiate the game. Or as the Chicago Tribune described it, “Hanlon and Ryan filled the thankless positions.”10

Ryan had many talents, but media relations was not one of them. On July 1, 1892, after an 11-3 home loss to Baltimore, Ryan “assaulted a reporter of the Evening News named George Bechel. The latter had criticised [sic] Ryan and when he appeared in the club house after the game Ryan picked a quarrel with him. He then attacked him, using him up pretty badly.”11 It was not an isolated incident. Five years earlier, baseball gossip columns across the country printed a brief story that said “Ryan slugged the magnificent Chicago reporter in Pittsburgh the other day.”12

Ryan’s 1893 season was shortened to 83 games because of a serious injury. After finishing a series in Cleveland on August 5, the Colts boarded a train bound for Chicago. The sleeper cars in the back of the train flew off the track in Lindsey, Ohio, and crashed into a freight train that was parked on a nearby sidetrack. His hometown friend Kittridge suffered a severe cut on his head and Ryan sustained significant cuts on his head and legs. Other Colts players were mildly hurt but able to continue their seasons, unlike Kittridge and Ryan. Three passengers were killed in the accident.13

The following season was a strong bounce-back year for Ryan. He had career-highs in batting average (.357) and on-base percentage (.422). Many other hitters also performed well in 1894 because pitchers were adjusting to the 60-foot, six-inch mound distance, which was implemented the year before. Ryan went 5-for-5 in Chicago’s 24-6 home win over Pittsburgh on July 25.

The day after his five-hit game, Ryan’s frequent drinking was brought up in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. In a column sub-headlined “Lushing Ball Players Should Be Punished More Severely,” the newspaper criticized clubs for not disciplining players more firmly for drunkenness. “The lusher has no place in base ball, but the failure of the New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Chicago and other clubs to punish offenders is not calculated to put a stop to a practice hurtful to the players and unfair to their clubs and the public. (Mike) Tiernan and (Shorty) Fuller of New York; (Tom) Kinslow, Con Daily, (George) Treadway and (Tommy) Corcoran of the Brooklyns; (Jimmy) Ryan of Chicago, (Bill) Hussamer [sic] and (Duke) Esper of the Washingtons, (Jack) Taylor of the Philadelphias and (Theodore) Breitenstein are players who have escaped with a reprimand or a slight fine,” the article said.14

In 1895, Ryan hit .317 in 108 games. He had another strong season in 1896, batting .305 in 128 games. On June 3 of that year, Ryan had another off-field incident. He got into an argument with a pullman conductor on an overnight train trip from New York to Boston. The Boston Globe said the altercation culminated when Ryan “got in one upper cut before Anson stopped the fun.”15

Others around the game noticed and applauded Ryan’s consistent on-field success. “Baseball patrons in Chicago should appreciate that man, for there are no better players to be found anywhere. I have admired him for years, not only for his ability on the field but as a man,” New York Giants manager Bill Joyce said in 1896.16 Ryan turned in another valuable season in 1897, hitting .300 in 136 games. On July 29 he hit a grand slam and scored five runs in Chicago’s record-setting 36-7 win over Louisville. As of March 2021, the Colts’ performance that day remains the most runs by a major-league team in a single game.

The 1897 season was Anson’s last managing Chicago. Ryan clashed with Anson through the years. “Ryan and his big captain have had a great many wars of words,” a national baseball gossip column once said, before going on to describe the time Anson told Ryan he was going to “smash you in the face,” to which Ryan replied to Anson that he would “shoot you full of holes.”17 Anson’s departure led to Chicago’s National League entry being nicknamed “Orphans” in 1898.18 Under new manager Tom Burns, Ryan played in 144 games and hit a team-leading .323 that year. Chicago finished eighth in 1899 and sixth in 1900, which proved to be Ryan’s final two seasons there. As of March 2021, Ryan is atop or among the Chicago Cubs’ career leaderboard in various categories. He has the most triples (142), the second-most runs (1,410), the third-most stolen bases (370), the eighth-most hits (2,084), and the eighth-most doubles (362) in franchise history.

After the 1900 season, American League and National League executives discussed shortening the 60-foot, six-inch pitching distance. Ryan had credibility on this topic, since he experienced more than 2,000 plate appearances in the 1880s when the pitcher was only 50 feet from the batter. “When the pitching distance was 50 feet the pitchers worked just as hard as they do now. Then, as now, they threw the ball with all their might, and the short distance was simply murder. If Rusie, Ferguson, Buffington [sic], or Whitney came at you full speed that short distance off you had to duck or die. Good batting was almost impossible,” Ryan said on December 30, 1900.19

In 1901, the Class A Western League formed and its delegates hoped to lure active major leaguers to be player/managers. Ryan signed on to be the player/manager of the St. Paul Saints, who finished 69-54, in second place, 10 games behind the first-place Kansas City Blues. On January 21, 1902, he joined the American League’s Washington Senators, his first stint with an American League team.20 Veterans Ryan (age 39) and Ed Delahanty (age 34) had the two best batting averages and hit totals on the Senators. Ryan had a 21-game hitting streak from May 23 to June 16, the longest hitting streak of his career. In 1903, Ryan turned 40 and played his final major-league season as the oldest player in the American League. He appeared in 114 games for the Senators and hit .249, the lowest batting average of his career.

Ryan spent 18 years in the majors, compiling 2,513 hits, 118 home runs, and 419 stolen bases. Among players who retired before 1911, he had the ninth-most career hits. As of 1920, he was fifth on the all-time home run list.21 He hit .300 or better in 11 different full seasons and walked 804 times, compared to only 491 strikeouts. In different seasons throughout his career, Ryan led the National League in doubles, extra-base hits, hits, home runs, plate appearances, slugging percentage, and total bases. He led off 22 games with a homer, which was the major-league career record until Eddie Yost broke it decades later.22

Ryan was also one of the best defensive outfielders of his era. He had a formidable throwing arm and, as of March 2021, he is still the National League’s career leader in outfield assists with 375. Ryan described his throwing capabilities to the St. Louis Republic in January of 1905, saying “I could throw without stopping to take a forward stride with either foot before letting go the ball. I used to catch runners at the plate right along.”23 At different seasons in his career, Ryan led the National League in double plays as an outfielder, outfield assists, and range factor as an outfielder.

Even though Ryan played his last major league game in 1903, he did not hang up his spikes that year. He was a playing manager in the minor leagues for the Colorado Springs Millionaires in 1904, the Evansville River Rats in 1905 and 1906, and the Montgomery Senators in 1908. Ryan played his final professional game at age 45 with Montgomery. When minor league seasons ended, he returned to his offseason home in Chicago and occasionally watched late-season Cubs games in person at West Side Grounds.24 After baseball, Ryan worked in law enforcement as a bailiff and as a deputy sheriff for Cook County, Illinois.25 In his down time, he dusted off his bat and glove and played for a Chicago community team in Rogers Park until 1915, when he was 52 years old.26

On September 17, 1923, Ryan and numerous other former major leaguers joined Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in paying tribute to Cap Anson at a dedication of Anson’s new grave marker in Chicago.27 Forty two days later, Ryan was sitting on his porch in Chicago when he had a heart attack and died. He was survived by his wife Elizabeth.28 They did not have any children. Ryan was 60 years old. “He was known as the most accurate and clever thrower in the history of the game,” Hugh Fullerton opined in the Chicago Tribune the day after Ryan’s passing.29 Ryan is buried at Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois.

Ryan was elected to the Chicago Cubs Hall of Fame via a fan vote in 1982.30 He has been considered for the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, making it onto initial screening lists or Veterans Committee ballots a dozen times over the years.31

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also used Baseball-Reference.com, FamilySearch.org, Newspapers.com, Retrosheet.org, and The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Peter Morris assisted with the 1870s US Census listings.

Notes

1 US Census Bureau, 1870 US Census.

2 Arthur Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan,” Society for American Baseball Research, http://research.sabr.org/journals/assist-for-jimmy-ryan.

3 “Alumni in the Majors,” 2011 Boston College Baseball Media Guide, 37.

4 “Sporting Affairs,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1885: 2.

5 Steve Treder, “Bats right, throws left: The best players in major league history,” The Hardball Times, February 10, 2009, https://tht.fangraphs.com/bats-right-throws-left-the-best-players-in-major-league-history/.

6 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2: The Hall of Famers and Memorable Personalities Who Shaped the Game (Volume 2) (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Original, 2011), 2011.

7 Brian Aldridge, History of the Chicago Cubs 1876-1900 (Wheaton, Illinois: Brian Aldridge Publisher, 2021): 33.

8 Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan.”

9 Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan.”

10 “Anson Finds a Club to Beat,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1892: 6.

11 “Baseball Items,” The Kansas City Press, September 16, 1892: unknown page number.

12 “Gossip of the Game,” Springfield Daily Herald, October 28, 1887: 5.

13 “Made a Bad Wreck,” Nebraska State Journal, August 7, 1893: 1.

14 “No Draw This Time,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 26, 1894: 2.

15 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, June 5, 1896: 9.

16 Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan.”

17 “Base Ball Gossip,” Dollar Weekly News, June 29, 1889: 3.

18 David Fleitz, Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Forgotten Members of the Hall of Fame (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 212.

19 “Will Change Rules,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), December 31, 1900: 4.

20 “Jimmy Ryan Signs with Washington,” Chicago Tribune, January 22, 1902: 8.

21 Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan.”

22 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2: The Hall of Famers and Memorable Personalities Who Shaped the Game (Volume 2) (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Original, 2011), 2011.

23 “Method of Throwing Balls Has Changed in Two Decades,” St. Louis Republic, January 22, 1905: unknown page number.

24 George R. Matthews, When the Cubs Won It All: The 1908 Championship Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010), 147.

25 Illinois Deaths and Stillbirths Records, 1916-1947.

26 Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan.”

27 “Anson Honored by Big Men of Baseball World at Unveiling,” Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), September 17, 1923: 16.

28 Illinois Deaths and Stillbirths Records, 1916-1947.

29 Hugh Fullerton, “Ryan, One of Anson’s Old Stars, Is Dead,” Chicago Tribune, October 30, 1923: 18.

30 Ahrens, “An Assist for Jimmy Ryan.”

31 Graham Womack, “Known Veterans & Era Committee candidates, 1953-current,” https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1yuFmN8hBv73rxZiaR1OdputmK2_4a09wuuNrJP05Y28/edit#gid=0

Full Name

James P. Ryan

Born

February 11, 1863 at Clinton, MA (USA)

Died

October 29, 1923 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.