Alex Grammas

There was never an Alex Grammas question on Family Feud. However, if Richard Dawson, the late and long-time host of the popular game show, were to have asked a hundred of his contemporaries how they remembered Grammas, the survey would invariably point to three answers: flawless fielding, excellence as a third-base coach, and his Hellenic heritage. As a National League utility infielder for ten years, Grammas drew favorable comparisons to a young Phil Rizzuto. After retiring, he was a third-base coach for a quarter-century, mainly for teams managed by Sparky Anderson. Forever proud of his ancestry, Grammas in 1976 became the first Greek-American ever to manage a major-league team for a full season.

Peter Grammatikakis was a Greek immigrant to the United States who left his home in Agios Dimitrios for Birmingham, Alabama, early in the 20th century. Attracted by the reputation of the Southern metropolis as a “Magic City,” he truncated his name to Grammas and established himself in the wholesale candy trade. Peter married Angeline, the American-born daughter of Greek immigrants from Geraki. Their second son Alexander Peter was born in Birmingham on April 3, 1926. Both Alex and his older brother, Cameron, loved baseball, and seized any opportunity to pursue their national pastime between grammar school and Greek school. Both brothers served in World War II before playing college baseball at Mississippi State University.

Alex maintained that Cameron was the better player: “He has played A-ball at Colorado Springs and hit about .335. … They were going to send him back out to Colorado Springs the following year. [He] just didn’t want to do it, so he quit. I wish he hadn’t because he would have made it — no question about it,” Grammas recalled in a 1998 book on Greeks in the game.

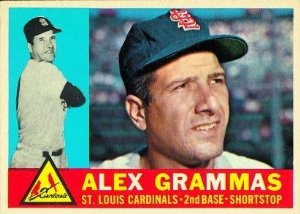

After he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business in 1949, Alex was signed to his first professional contract by Doug Minor of the Chicago White Sox. He batted .327 for Muskegon in the Class A Central League, and was promoted in 1950 to Memphis, where he led Southern Association shortstops in fielding. Before that season, on January 29, 1950, Alex married the former Tula Triantos. Traded to the Cincinnati Reds organization in 1951, he continued to impress with his quick fielding and timely hitting. On loan to Kansas City of the American Association one year, he led the league’s shortstops in putouts and assists. The Pittsburgh Pirates valued Grammas and his defensive abilities enough to look into acquiring him in a proposed six-player trade in 1952 with Ralph Kiner as the headliner in the swap. Although the Pittsburgh deal fell through, the Reds offered Grammas in another trade the following winter. On December 2, 1953, he was dealt to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Jack Crimian and $100,000.

Measuring 6 feet and weighing 175 pounds, Grammas could not have been more excited than to make his major-league debut as a Cardinal: “I was hoping [they] would get me. I can’t think of anything better than playing next to Red Schoendienst. He’s the best there is in the majors,” Grammas said. Finishing tied for third in the National League with a record of 83-71 in 1953, the Cardinals under new owner August A. Busch viewed Grammas as “the missing piece” to transform the team into bona-fide contenders.

Unfortunately, Grammas’s enthusiasm proved costly in his first spring training with St. Louis. On February 21, 1954, he injured his right arm during a sliding drill. Although X-rays proved negative and Grammas made the varsity squad, he spent his rookie year trying to regain confidence after suffering the painful injury. A year after batting .307 in the minor leagues, he hit only .264 with 57 runs and 29 RBIs playing for the Cardinals. Grammas scored three runs (once after reaching on an error and twice after walking) before collecting his first big-league hit, a single off Cincinnati’s Harry Perkowski on April 19, 1954, in a 6-3 Cards win at home. And he did not hit his first home run until September 3, when he parked a Paul Minner pitch in a losing effort to the Chicago Cubs. (Grammas had gone 0-for-4 against Minner in his big-league debut, a 13-4 Opening Day loss to the Cubs at Busch Stadium in St. Louis on April 13.) As for the Cardinals, they finished the season in sixth place out of eight teams with a record of 72-82, 25 games behind the New York Giants.

Although Grammas led the senior circuit in fielding average in 1955, he batted only .240. Early in the 1956 season, on May 16, he was traded back to Cincinnati along with outfielder Joe Frazier for infielder-outfielder Chuck Harmon. After years of obscurity, the Reds found themselves in a pennant race with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Milwaukee Braves. Manager Birdie Tebbetts credited Alex as “a big difference in our ballclub … since we’ve been using him”; The Reds finished third, two games behind Brooklyn and one behind Milwaukee. His confidence improved in 1957, particularly on the heels of a triple play executed against the New York Yankees in a spring training contest. Gil McDougald was in scoring position at second base with Mickey Mantle on first when Yogi Berra hit a line drive to the Cincinnati shortstop. Grammas put McDougald out at second, then caught Mantle in a rundown. During the 1957 season, Grammas, playing behind All Stars Johnny Temple, Roy McMillan, and Don Hoak, had only 99 at-bats. He hit .303, second on the Reds only to Frank Robinson’s .322. The following campaign marked Grammas’ worst pro season to-date.

The 1958 Redlegs finished below .500 and in mid-August Tebbetts was replaced by Jimmy Dykes when Cincinnati dropped toward last place. Despite the team rebounding and eventually finishing fourth, Grammas lost the shortstop position in mid-July and primarily played third base, along with several starts at second. His season batting average ended at .218, over 80 points lower than the previous year.

The Reds traded Grammas back to the Cardinals in a six-player deal on October 3, 1958. During his second tour of duty in St. Louis, he earned the reputation of carrying “a sharper bat, a better arm, surer hands, and can handle three positions well.” Batting .269 in 1959, Grammas, by now 33 years old, spent time teaching younger players the value of maintaining a proper attitude as a team player. Tim McCarver remembered:

“I was 17 years old when I first came up with the Cardinals, just up from high school. My first night on the bench [a September 1959 game], Henry Aaron was up with a couple of guys [on]. I liked Henry Aaron a lot growing up. I let out with one of those ‘Come on, Henry!’ or something to that effect. Everyone naturally looked at me and Alex Grammas came over and said, ‘You know, up here in the big leagues, we tend to cheer for our players, not the opposition.’ ”

Traded again on June 5, 1962, this time to the Cubs, Grammas completed his playing career in Chicago a year later. His lifetime statistics in ten National League seasons included 236 runs, 90 doubles, 10 triples, 12 home runs, 163 RBIs, and a .247 batting average. By now, the Grammas family had expanded to include daughters Lynn and Mary Ann, along with twin sons Peter and Alexis. The patriarch needed to plan for his family’s future.

During the offseasons, Grammas worked in the produce business with his uncles. The experience was valuable preparation for a supermarket venture he entered into with his friend Harry Walker. The business partnership proved to be an important strategic alliance when Walker was hired to manage the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1965. After managing the Cubs’ Texas League affiliate at Fort Worth in 1964, Grammas was hired by Walker and began the first of 25 seasons as a major-league third-base coach. He remained a Pittsburgh coach for five years before resigning at the end of the 1969 season, having managed the last five contests the Bucs played that on an interim basis after Larry Shepard was fired. Pittsburgh General manager Joe L. Brown offered a glowing recommendation of Grammas, both as a coach and as a man. When the obscure 35-year-old George Lee “Sparky” Anderson was hired to manage the Cincinnati Reds in 1970, Grammas was his choice as first lieutenant:

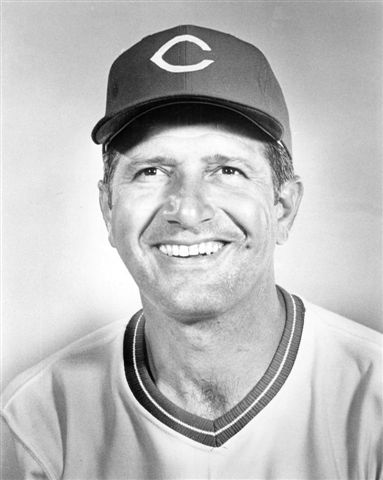

“I coached third base myself for Preston Gomez the year before. On my one season on that job, I watched all the other third-base coaches in the league. I thought Grammas was the best and Eddie Yost of the Mets, next best,” Anderson told Si Burick of the Dayton Daily News. “I told [general manager Bob] Howsam I needed a real professional at third base, and I’d like to offer the job to Grammas. I called Alex and told him I was hoping for a relationship like [Al Lopez] with the White Sox coaches.” For 19 of the next 22 years, Grammas remained a valuable member of Sparky Anderson’s coaching staffs.

As the Reds prepared to open their new Riverfront Stadium, a dynasty was dawning in Cincinnati. Nobody dared to ask “Sparky Who?” after the Reds opened the 1970 season with a torrid .700 winning percentage in their first 100 games before tapering off, as it were, to 102-60 and a National League West Division title. The Reds swept the Pirates in three games during the NLCS before losing in the World Series to Baltimore. After the Reds disappointed in 1971, tumbling to a fourth-place tie with Houston, they pulled off a blockbuster deal with the Houston Astros, bringing, among others, All-Star and eventual Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Morgan to the Queen City. Grammas helped Morgan improve his defensive abilities and later successfully converted outfielder Pete Rose to a third baseman. However, if you ask Alex today, he will reserve his highest praise for his prize pupil, a young shortstop from Venezuela named Dave Concepción:

As the Reds prepared to open their new Riverfront Stadium, a dynasty was dawning in Cincinnati. Nobody dared to ask “Sparky Who?” after the Reds opened the 1970 season with a torrid .700 winning percentage in their first 100 games before tapering off, as it were, to 102-60 and a National League West Division title. The Reds swept the Pirates in three games during the NLCS before losing in the World Series to Baltimore. After the Reds disappointed in 1971, tumbling to a fourth-place tie with Houston, they pulled off a blockbuster deal with the Houston Astros, bringing, among others, All-Star and eventual Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Morgan to the Queen City. Grammas helped Morgan improve his defensive abilities and later successfully converted outfielder Pete Rose to a third baseman. However, if you ask Alex today, he will reserve his highest praise for his prize pupil, a young shortstop from Venezuela named Dave Concepción:

“You’re talking about a guy I love. He’s probably the finest infielder I ever had the pleasure to work with. If not the most talented, he’s near the top. He even named his son after me, David Alejandro,” Grammas said in a 2009 interview. As Sparky Anderson later told sports reporter Dan Ewald, “Concepción had the tools but he needed a lot of polish. Alex Grammas spent hour after hour teaching him the tricks. Grammas and David sweat and bled from all the work they put in together. Grammas hit David more groundballs than Donald Trump has dollar bills … and Grammas taught him to concentrate on situations. It wasn’t good enough to field the ball. He had to learn what to do after he got it.”

The Reds won the NL West easily in 1972 before facing a challenging Pittsburgh Pirates team in the NLCS. The Reds and Pirates split the first four contests, forcing a deciding Game Five before a packed house in Cincinnati. Pittsburgh was leading, 3-2, as the game entered the bottom of the ninth inning. As Pirates reliever Dave Giusti waited to deliver the first pitch to Johnny Bench, a commotion ensued at home plate. Grammas remembered “standing at third base and I didn’t know what was going on.” He was later told that Bench’s mother wandered down to the railing to offer words of encouragement, advising, “Johnny, this is it. Let’s go. Do something.” Bench, the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1972, listened to his mother and tied the game with a leadoff home run to right field. A pair of singles by Tony Perez and Denis Menke brought Bob Moose in from the Pittsburgh bullpen. George Foster, at second base as a pinch-runner for Perez, made it to third on Cesar Geronimo’s fly ball. With two outs after a Darrel Chaney popup, the entire stadium seemed to be on its feet as Moose uncorked a wild pitch to pinch-hitter Hal McRae, sending Foster racing safely home for the 4-3 victory. For the second time in three years, Cincinnati was going to the World Series (which they lost to Oakland in seven games). For Grammas, it was “the most spine-tingling game I was ever connected with.”

The Big Red Machine won their division again in 1973, although losing to the New York Mets in the NLCS, before going all the way in 1975, defeating the Boston Red Sox in a sterling seven-game World Series. Game Seven was Alex’s last in a Cincinnati uniform before he was hired to manage the Milwaukee Brewers. Even as a player, he was deemed the most likely of his teammates to succeed as a manager. Now he would be challenged to manage a struggling franchise that had never in its brief history won more than 76 games per season. Not even the presence of Hank Aaron could prevent a late-season meltdown in 1975, as the Brewers lost 59 of their last 84 games to finish at 68-94. Despite the financial security of a three-year contract, Grammas had his work cut out for him:

“When you take a ballclub that ended up the way the Brewers did last year, you’ve really got to be happy if you can wind up playing .500 ball. That means winning 13 games more. That’s more realistic than to think we can win the pennant,” he said. Leading the Brewers both on the field and by example was, once again, Hank Aaron. Grammas admitted years later to Larry Stone of the Seattle Times that he “was proud to have Hank on [his] team.” describing the home-run king as “the kind of guy everybody liked.” Aaron was the first to admit that by 1976 his skills were deteriorating. Facing California’s Dick Drago at County Stadium on July 20, Aaron hit his 755th career home run without any accompanying media fanfare. Nobody would have known it would be his last in a major-league uniform — and the highlight of an otherwise disappointing season for the Brewers.

An omen of the 1976 campaign presented itself early in the schedule on April 10. The Brewers trailed the visiting New York Yankees 9-6 in the bottom of the ninth inning when third baseman Don Money hit a walk-off grand slam. Or did he? Before delivering the pitch to Money, Yankees reliever Dave Pagan did not notice first base umpire and fellow Canadian Jim McKean call time out as requested by the Yankees’ Chris Chambliss. Never one to shy away from a protest, Yankees manager Billy Martin insisted that the home run should be nullified. McKean upheld Martin’s protest, and Money subsequently flied out. The Brew Crew’s rally was stymied as New York topped Milwaukee, 9-7.

Despite the promise of success with a Sparky Anderson protégé at the helm, the Brewers ended the 1976 season in the American League East cellar; posting a record of 66-95, they finished 32 games behind the Yankees. Grammas took the disappointment in stride, offering that “it’s a little difficult to adjust to … but you have to be realistic. If not, you drive yourself crazy and I have no intention of driving myself crazy.”

Clearly a roster overhaul was in order for the Brewers in 1977. Power hitting George Scott was traded back to the Boston Red Sox for slugging first baseman Cecil Cooper after calling the Brewers “the laughingstock of baseball.” After a weak season at the plate, catcher Darrell Porter was packaged with pitcher Jim Colborn to the Kansas City Royals for a trio of young players, outfielder Jim Wohlford, pitcher Bob McClure, and utilityman Jamie Quirk. Another player acquired via the free-agent route was third baseman Sal Bando. With Don Money moving to second base and Robin Yount emerging as one of the brightest young shortstops in baseball, the Brewers opened the 1977 season with a formidable infield. If only infielders could pitch. Jerry Augustine led the squad with 18 losses (and 12 wins) for a team that went 67-95. Only the haplessness of the expansion Toronto Blue Jays prevented a second consecutive last-place finish for the Brewers.

Despite enjoying popularity among the fans in Milwaukee, Grammas lacked the support of all his players. The alienation began when he imported the dress code from Cincinnati that prohibited players from sporting facial hair. A significant minority of the Milwaukee roster in 1975 sported Fu Manchu mustaches. Along with Colborn, Porter, Scott, and Yount, Brewers players Gorman Thomas, Kurt Bevacqua, and Pete Broberg were all depicted on their 1976 Topps cards wearing their Fu Manchus. Under the stewardship of Grammas, the free-spirited players were required to shave their whiskers against their will by Opening Day 1976. Discontent with the manager continued in 1977 to the point that utility player Mike Hegan told reporter Lou Fitzgerald that “Alex Grammas is a nice guy, but as a manager he makes a good third-base coach.”

Hegan’s immediate release proved to be a pyrrhic victory for Alex. The manager was not given the opportunity to complete his three-year contract as he became one of the casualties in the November 20, 1977 front-office upheaval known as the Saturday Night Massacre. Again sardonic in his outlook, Grammas allowed that “I’m sure the Brewers are going to be a much better team.” He was right; they went 93-69 for George Bamberger in 1978.

When one door closed in Milwaukee, another, in Cincinnati, was reopened as Grammas returned to the Reds in 1978. Sparky Anderson was ecstatic that “Grammas is back with us. … He will coach again at third base. I have said ‘Greek’ is the best at that job, so there is where he will be stationed.” It was a brief homecoming for Alex as the Reds finished in second place. Under new general manager Dick Wagner, second place was no longer good enough, and Anderson was fired. While Sparky began the 1979 season in exile, Alex had accepted the Atlanta Braves’ offer to coach third base. However, when Anderson was hired to manage the Detroit Tigers on June 12, Grammas seemed to be a natural fit to the coaching staff:

“With Grammas, I had such a good rapport from the bench to the third-base coach’s box that, after a while, we didn’t even have a regular sign. In the early days, I found myself giving him the wrong sign at times, but he realized it and would change it to the right thing. Once in a while, he’d even change the right sign, like a quarterback checking off the coach’s play at the line of scrimmage because the defensive alignment wasn’t right for the strategy. Alex would hear a whistle on the other side and realize they anticipated what we intended to do, so he did something else.”

Alex followed Sparky to Detroit in 1980, and had the opportunity to coach two more bright infield pupils, shortstop Alan Trammell and second baseman Lou Whitaker. Although experts scoffed at the manager’s prediction of a world championship within five years, the Tigers produced precisely that. After winning 35 of their first 40 games in 1984, the Tigers spent the entire season in first place before dispatching the Kansas City Royals three games during the ALCS, then defeating the San Diego Padres, four games to one, in the World Series.

With Detroit struggling in its quest to defend its title in 1985, a left-handed starter was on general manager Bill Lajoie’s shopping list. Meanwhile, the Texas Rangers had a southpaw they were eager to trade. Remembering him as “the best pitcher — not only in the American League,” Grammas recommended the pitcher in a trade. On June 20, 1985, the Tigers welcomed native Detroiter Frank Tanana back home. The crafty southpaw lent stability to the Tigers’ rotation for eight years, and was the winning pitcher in the decisive final game of the 1987 season, pitching a 1-0 shutout over the Blue Jays to win the AL East over second-place Toronto.

Although the Tigers contended yet again in 1988, success would be short-lived as Detroit in 1989 posted the worst record in baseball, 59-103. Veterans who had contributed to the 1984 success were ineffective, retired, or playing elsewhere. (Jack Morris would join them as an ex-Tiger in 1991.) They were replaced by a new batch of players, younger and cheaper and uncomfortable with an older coaching staff; these players were not afraid to voice their concerns to the front office. Consequently, despite winning 84 games in 1991, the Tigers released three of their coaches, among them Alex Grammas. At 65 years old, he decided it was time to retire.

His baseball career behind him, Grammas returned to Birmingham to pursue his favorite hobbies, fishing and golf. In 1992, he reaped the dividends of the eight years he spent at Greek school as a child when he traveled to Greece for the first time.

“All my life, my father was telling me good things about Greece,” Grammas recalled. “When he was talking, I was laughing, but when I saw with my own eyes, I realized he hadn’t said enough about Greece. I love Greece very much. … When I walked up to the Acropolis and saw the Parthenon, the hairs on my head were standing straight up. I couldn’t believe it.” He returned to Greece several times, and a later recent trip was the most special for him:

“I decided to take the entire family to Greece — all 21 of them. I thought it was important for my grandchildren to learn about their heritage and see where their ancestors came from,” Grammas said in 2009. “We visited Athens, took a cruise of the [Greek] islands, and stayed overnight at the house where my father was born. I’ll tell you — the day we arrived, they announced Athens was getting the Olympics. The entire city went mad. You’ve never seen anything like it.”

Alex Grammas devoted more than a half-century of his life to baseball as a player, coach, and manager. He played ten years in the major leagues, coached an additional 25, and earned three World Series rings. He gained the respect and admiration of students and peers and delighted in watching his pupils become stars. Dave Concepción became one of the most successful shortstops in Cincinnati before teaching the trade to another budding superstar, Barry Larkin. Grammas continued to live in Birmingham and he enjoyed good health in retirement. His philosophy on life advised that “nothing can be stopped except time, so please enjoy every minute.”

The Family Feud survey says that Alex Grammas listened to his own advice.

He died at the age of 93 on September 13, 2019.

An updated version of this biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Matt Bohn, George Demetriou, Alex Grammas, Tula Grammas, Merle Harmon, Aaron Honoré, Thomas Karn, Randy Messel, Larry Moffi, and Al Yellon.

Sources

Aaron, Hank and Lonnie Wheeler. I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1991.

Jack H. Berger, ed. Pittsburgh Pirates 1969 Media Guide. Pittsburgh: The Pittsburgh Pirates, 1969.

Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella. Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams. Toronto: Sport Media Publishing Inc., 2005.

Eisenath, Mike. The Cardinals Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999.

Fehler, Gene. Tales From Baseball’s Golden Age. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2000.

Finoli, David and Bill Ranier. The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003.

Honoré, Aaron J. Beards: On Men, On Women, On Gods and More — How Facial Hair Serves as Both a Means to An End and An End of Communication. New York: Fordham University, 2005.

Mishler, Todd. Baseball in Beertown. Neenah, Wisconsin: Big Earth Publishing, 2005.

Preston, Joseph G. Major League Baseball in the 1970s: A Modern Game Emerges. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004.

Swirsky, Seth. Every Pitcher Tells a Story: Letters Gathered by a Devoted Baseball Fan. New York: Crown Publishing Group, 1999.

Zervos, Diamantis. Baseball’s Golden Greeks: The First Forty Years, 1934-1974. Canton, Massachusetts: Aegean Books International, 1998.

Halofan, Rev. “The 100 Greatest Angels: Frank Tanana,” on Halos Heaven. February 13, 2006. http://www.halosheaven.com/story/2006/2/14/23549/1427. Accessed February 21, 2009.

Stone, Larry. “Little Fanfare Surrounds Aaron’s HR No. 755,” Seattle Times, July 22, 2007.

Full Name

Alexander Peter Grammas

Born

April 3, 1926 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

September 13, 2019 at Vestavia, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.