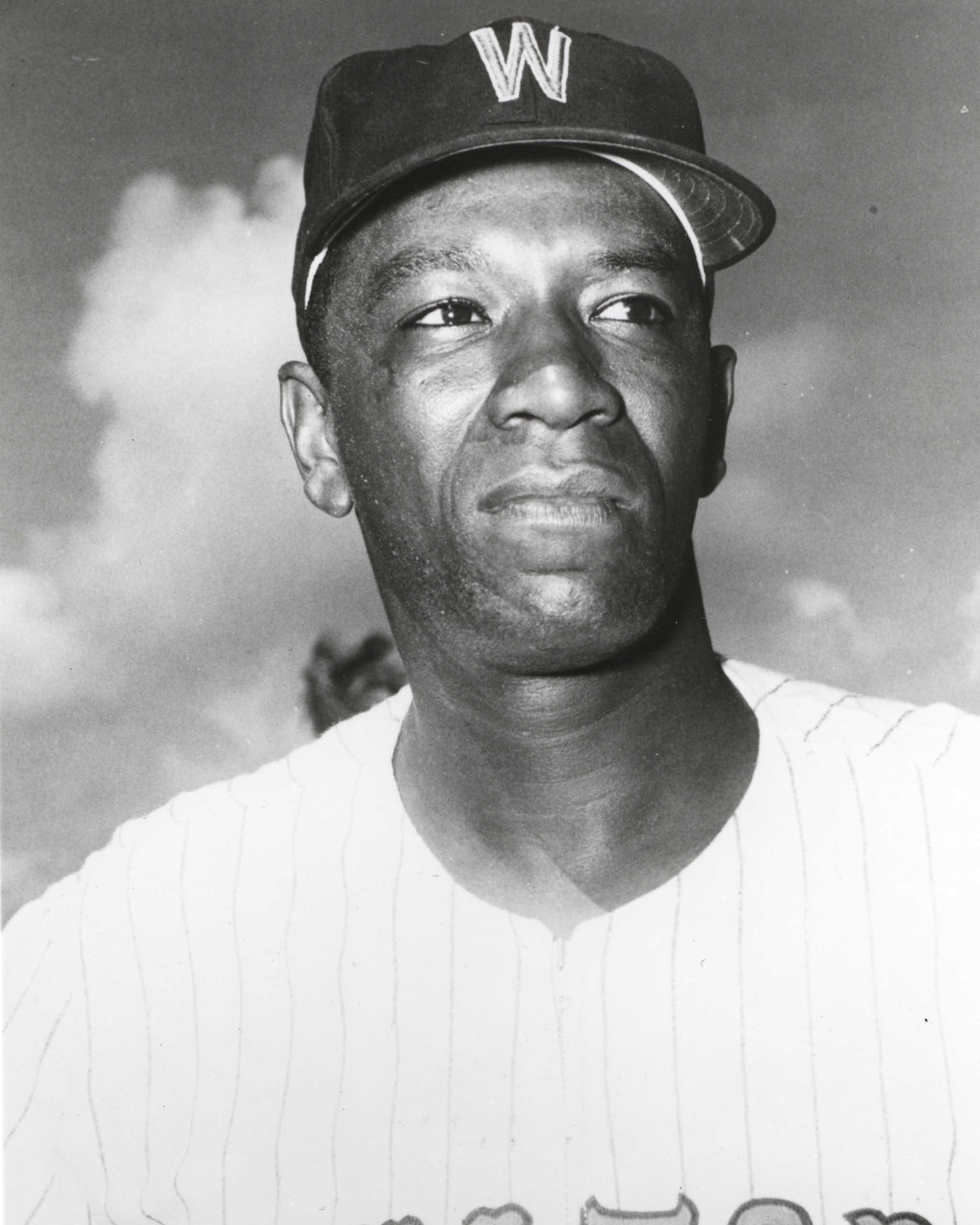

Bennie Daniels

The expansion Washington Senators had little to cheer about at the end of their inaugural season in 1961. They had lost 100 games and finished in the cellar, tied with the Kansas City A’s. Their hitting was dead last in the league. If there were any bright spots to look forward to in 1962, they were centered on a pitching staff that included a tall right-hander named Bennie Daniels who led the staff with a 12-11 record, the only Senator with a winning record. Daniels had started in Organized Baseball 11 years earlier and spent most of his time in the Pittsburgh farm system. After joining the Senators in a trade following the Pirates’ championship 1960 season, Daniels seemed to have arrived as a starting pitcher in the major leagues. As it turned out, he did better with the Senators than he had with the Pirates.

The expansion Washington Senators had little to cheer about at the end of their inaugural season in 1961. They had lost 100 games and finished in the cellar, tied with the Kansas City A’s. Their hitting was dead last in the league. If there were any bright spots to look forward to in 1962, they were centered on a pitching staff that included a tall right-hander named Bennie Daniels who led the staff with a 12-11 record, the only Senator with a winning record. Daniels had started in Organized Baseball 11 years earlier and spent most of his time in the Pittsburgh farm system. After joining the Senators in a trade following the Pirates’ championship 1960 season, Daniels seemed to have arrived as a starting pitcher in the major leagues. As it turned out, he did better with the Senators than he had with the Pirates.

Ben J. Daniels was born on June 17, 1932, to Sallie Daniels and her husband, Ben Daniels, Sr., a farmer in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The 1940 US Census shows the family living in Cherokee, a small town in the northwestern corner of Alabama about 100 miles from Tuscaloosa. Along with Ben’s four young siblings, and his parents, the Daniels household included an older sister and her family as well as his aunt and uncle.1 In 1945 Bennie and his family moved to Compton, California, part of the 1940s migration out of the South. In 1957 Daniels recalled that he had not been expected to survive childhood. “I was sickly all my life until our family moved to California,” he said. “As a matter of fact, my mother told me later that I wasn’t expected to live. I didn’t have any fatal disease; I was just sickly and scrawny. But I began to sprout like a weed after we moved to Compton.”2

In Compton a climate favorable to health and an interest in sports allowed Daniels to outgrow childhood illnesses. He grew to 6-feet-2 and 190 pounds. He excelled in baseball, basketball, and track, and was once clocked at 10.4 in the 100-yard dash. Daniels graduated from Compton High School having made All-Coast in baseball and basketball. His performance in high-school and American Legion ball attracted interest leading to his being signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates by longtime major-league scout Rosie Gilhousen in July 1951.3

Daniels was assigned to the Great Falls (Montana) Electrics in the Class C Pioneer League. His chances of making the major leagues at that time were daunting. In 1951 there were 50 minor leagues. The Pioneer League was in the lower echelons. In those days fewer than one in 15 players made it to the majors, even if just for a cup of coffee.

His first two years in the minors proved inauspicious. At Great Falls he posted a 2-4 record and at Modesto of the California League the next season, hobbled by a case of ptomaine poisoning, he went 9-14.4 Then, as with many young men in the early 1950s during the Korean War era, he was drafted into the US Army. Stationed in Germany for most of his hitch, Daniels maintained his athleticism, playing baseball and football for the 1st Infantry Division Artillery team.5

Discharged in 1955, Daniels was sent back by the Pirates to the Pioneer League, this time with Billings. He fashioned a solid 10-6 start before being promoted to the Lincoln Chiefs in the Class A Western League. Pitching creditably enough, he returned to Lincoln in 1956 and experienced a breakthrough season, winning his first ten games and finishing 15-3, his .833 winning percentage the best in the league. Daniels showed he could hit too, fashioning a .325 batting average with eight home runs and 38 RBIs and logging some time as a position player. While his hitting was outstanding, especially for a pitcher, Daniels was overshadowed by teammate Dick Stuart, who hit 66 home runs. Daniels was selected to the league’s All-Star team. His year ended on a further good note as he married Sue Irving on December 17.6 They had met at spring training at Huntsville, Texas.7 The marriage produced two children, son Michael and daughter Vickie.

Daniels’ performance earned him a promotion to the Hollywood Stars in the Pacific Coast League for the 1957 season. He picked up right where he left off, winning 17 games. Early in the season manager Clyde King described Daniels’ pitching style: “He has one of the best sinking fastballs in the game.” Teammate Ben Wade observed, “No other pitcher has shown me as much stuff in the league this year. Bennie’s not the fastest, but his ball moves more – real good breaking stuff. When he’s in trouble it’s because he is wild.”8

Wade also noted Daniels’ continued ability with the bat (Daniels hit .292 with five home runs that season) and his fielding ability. The observation on Daniels’ fielding was not an isolated comment. Several times during his career Daniels was described as a “fifth infielder” and occasionally was compared to Bobby Shantz, perhaps the best fielding pitcher of the era. His performance in 1957 earned him selection to the Pacific Coast League’s All Star team and promotion to the Pirates in September.

Daniels made his major-league debut on September 24, 1957, against the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was an auspicious occasion, the last major-league game played at Ebbets Field. Starting against the Dodgers, Daniels pitched seven innings before being relieved by Elroy Face. Daniels lost the game to Danny McDevitt but acquitted himself well, giving up just one earned run in his 2-0 loss. Of the game, Daniels later recalled, “It was a dark ballpark. … I was really shocked. I knew I was going to pitch, but I thought I was going to be coming in as a reliever, not as a starter. It was just amazing to be pitching in the big leagues.”9 And it was amazing, particularly because at the end of the previous season, as Daniels recalled years later, “I was going to retire from the game in 1957, but my wife said to hang with it.” 10

The 1957 Pittsburgh Pirates had finished tied for last, a finish the franchise was quite familiar with through the 1950s. The team’s fortunes took a decided turn for the better in 1958. Led by players like Bill Mazeroski and the incomparable Roberto Clemente, and a pitching staff anchored by the likes of Bob Friend, Vernon Law, and Elroy Face, the team shot to second place. The Pirates were on the threshold of becoming a bona-fide contender and were looking to augment their starting rotation.

After three solid seasons in the minors, Daniels had a legitimate shot to make the team. He did well, and at one point in spring training, manager Danny Murtaugh said, “Daniels will be one of my five starters.”11 Daniels, described as “the rave” of Pittsburgh’s training camp, was voted the “kid with the most potential” by sportswriters on the eve of the season’s opening game.12

Murtaugh’s comments notwithstanding, Daniels began the season with a few relief appearances before making three consecutive ineffective starts. By the end of May, with a 0-2 record, a 9.95 ERA, and 11 walks in 12 innings, Daniels was optioned to the Columbus Jets in the International League. He had not demonstrated the control necessary to be effective.

Once with Columbus, Daniels reverted to the form he had shown at Hollywood, finishing the season with a 14-6 record and a 2.31 ERA, among the league’s best. A teammate, catcher Dick Rand, described Daniels’ success – and the challenge he faced in getting back to the majors: “When he lets the fastball go, nobody – including Bennie, the catcher, and the hitter – knows just how it is going to move. The ball just moves and it moves different ways at different times. I suppose you could say it is ‘wildness’ but it’s the kind a lot of pitchers wish they had.”13

Daniels’ take was a bit different: “I can’t be sure myself just what it’s going to do.” But while Rand put a positive light on the movement of Daniels’ pitches, he in essence captured the main challenge Daniels faced, and never entirely overcame – lack of control. Recalled by the Pirates in September, Daniels did well in two starts, giving up just three earned runs in 15 innings.

As the 1959 season approached, Daniels found himself in almost the identical situation he faced the previous season: that of a well-regarded prospect hoping to make the majors. This time he succeeded in staying with the Pirates. As was the case in 1958, he began the season making a few relief appearances. Then, on May 3, he started against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Cardinals player-manager Solly Hemus provoked a near riot when he threw his bat at Daniels. Pittsburgh sportswriter Les Biederman intimated that Hemus did this to “light a fire” under the listless Cardinals, who had been playing poorly.14 Biederman said Daniels was so incensed at remarks Hemus made to him that he waited in the runway after the game to confront the manager. Only the intervention of Daniels’ teammates prevented a potentially ugly altercation between the 6-foot, 200-pound pitcher and the diminutive playing manager. Both Biederman’s article and a subsequent story in The Sporting News treated the incident as a typical baseball confrontation. 15 They missed the mark as to what had occurred.

In his book The Long Season, pitcher Jim Brosnan described Hemus’s effort to put a spark into the Cardinals by provoking Daniels earlier in the game. After purposely leaning into and being hit by a pitch, he yelled out to Daniels, “You black bastard.” Brosnan wrote, “If that was truly his intention he did it as awkwardly as he could. All he proved to me was that little men – or boys – shouldn’t play with sparks, as well as with matches.”16 Brosnan’s description of the incident suggests that his teammates felt the same about Hemus as he did.

The incident and its various perspectives were revealing of the insensitivity of things racial in baseball in 1959. Biederman’s article wryly compliments Hemus for his maneuvering the incident: “Maybe Solly Hemus knew what he was doing when he engineered the near riot at Forbes Field early in May.” In addition, Hemus admitted that he “simply had to do something to light a fire under the Cardinals.” Both Biederman and Hemus missed the real significance of what had occurred.

Brosnan was keenly aware of what was at stake when Hemus insulted Daniels. A dangerous and needless confrontation had been narrowly avoided. Ever increasingly, black players were not going to put up with prejudice. Daniels would not take such insults and essentially neither did the Cardinals players.

Years later, in David Halberstam’s October 1964, the incident is once again described, with repercussions of what took place more deeply understood. Hemus’s comment to Daniels had alienated Cardinals black players.17 Hemus not only misread not only the situation, he misread the temper of the changing times. It was a shortcoming that contributed to the loss of his job two years later. He never managed again.

Daniels’ 1959 season with the Pirates proved a disappointment. He finished 7-9 with a 5.45 ERA. Starting 12 games, he completed none. While his control seemed better (he walked only 39 in 100 innings pitched), he too often found himself pitching with a 3-2 count, a tough situation for any pitcher. Despite less than stellar pitching, he showed he still knew how to wield a bat. For the year, Daniels batted .310; on July 28, he hit his first major-league home run, a two-run shot off Larry Sherry of the Los Angeles Dodgers. The Pirates, after finishing second in 1958, disappointed in 1959, sliding back to fourth. Several players had off-years and the team was still looking for a dependable starter to back up Friend, Law, and Harvey Haddix, who had come over from the Reds after the 1958 season. The opportunity was there for Daniels to take.

Murtaugh still felt Daniels held the promise of better things to come. High on him going into the 1960 season, the manager observed, “I think Ben has as much as anyone in the league. He could be a big winner with us. At times last year, he showed it but there were other times he was just so-so. He’s big and strong and there were a couple of times when he pitched with just two days’ rest.”18

There were a few flashes of Daniels’ potential in 1960. In late May he started against the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax. Koufax was on that day throwing a one-hitter (a single by Daniels) and striking out ten. Daniels gave up only four hits in seven innings, and lost 1-0. Overall, though, he struggled with a 1-3 record and a 7.81 ERA as a combination reliever and starter. Five days after his 1-0 loss, the Pirates traded for Vinegar Bend Mizell from the Cardinals. The Pirates found their fourth starter. A month later Daniels was optioned to Columbus, where he posted an indifferent 4-9 record. Recalled on September 1, Daniels was on hand when the Pirates clinched their first pennant in 33 years. Daniels was voted a $4,208.97 half-share of the World Series receipts.19

Daniels had had three seasons to make a mark with Pittsburgh. Now a 29-year-old, with younger prospects on hand, his days in the Pirates organization were numbered. Shortly after the Pirates’ World Series victory over the Yankees, Mickey Vernon, a Pirates coach and a 20-year major-league player, was named manager of the expansion Washington Senators. In the expansion draft a few weeks later, the Senators took pitcher Bobby Shantz from the Yankees. Two days later they traded Shantz to Pittsburgh for first baseman R.C. Stevens, infielder Harry Bright, and Daniels. The Pirates said that despite Daniels’ “corking fastball, a fine curve and good control,” he had failed to develop as fast as they would have liked.20

Vernon felt that Daniels still had potential, and had lobbied Murtaugh to make the deal. They were both working in the offseason at a clothing store in Chester, Pennsylvania, and, as Vernon years later recalled, “We discussed and haggled back and forth between sales.”21

Daniels was coming to a team rushed into existence. After the 1960 World Series it was determined that the two major leagues would expand, the American League in 1961 and the National League in 1962. The hurried nature by which these two teams came to life was reflected in the talent pool they chose from in the expansion draft. Washington’s picks were a mixture of rookies not deemed worthy of protection from the draft, players who had failed to make a mark elsewhere, and over-the-hill veterans. That first season was indicative of what lay in store for the Senators. Before the franchise moved to Texas in 1972, the team never moved out of the second division.

For Daniels, however, 1961 represented the peak of his career. He started out slowly, losing his first three decisions before beating Detroit. Five days later he pitched a three-hit, complete-game 2-1 win against the Boston Red Sox. A week later he defeated the other expansion team, the Los Angeles Angels, 6-2 and hit his first American League home run. On July 30 he pitched hius first major-league shutout, a 4-0 six-hitter against the Kansas City Athletics. For a 61-100 ninth-place (out of ten) team, Daniels finished 12-11, leading the Senators in victories; his 3.44 ERA was among the league’s top 15 qualifiers. After the season Dick Donovan, considered the Senators’ ace based on the strength of his league-leading ERA, was traded to the Cleveland Indians, and with Donovan’s departure, Daniels became the ace of the staff.

Looking back on Daniels years later, teammate Chuck Hinton recalled, “He was a big gutsy guy, always pitching in pain, getting no support and losing. He was an inspiration to me, a big brother. He made no bones, no excuses when he lost. Just took his lumps. There wasn’t a guy in the league that didn’t like him. A real athlete.” Off the field, Hinton recalled, “He looked real good in clothes … never extravagant, just stylish.” Regarding Daniels’ hitting ability, Hinton noted that on one occasion he played the outfield for Washington.22

Daniels’ well-rounded athletic ability was illustrated during this time, when fans seeing number 21 warming up on the sidelines were confused. Knowing Daniels wore number 21, and was right handed, they could not understand why the pitcher was throwing left-handed. It was indeed Daniels. He was ambidextrous.23

Years later, looking back on his career, Daniels proudly recalled that one of the highlights of his career was pitching a complete-game five-hit win against the Detroit Tigers on Opening Day in 1962. That day was special to him because it was the only time President John F. Kennedy threw out the season’s opening pitch.24 It was also the first time an African American started on Opening Day for a Washington team.25 Daniels had been the Senators’ starting pitcher in the last game played at Griffith Stadium, in September 1961, and was the starting pitcher for the first game played at D.C. Stadium.26 (And his first major-league start was in the last game in Ebbets Field.)

With his Opening Day victory in 1962 Daniels reached the apex of his career. He lost his next ten decisions and was relegated to the bullpen. He never again approached the consistency he showed in 1961. Daniels began to experience nagging injuries, most seriously an irritation in his pitching elbow at the beginning of the 1962 season.27 Chuck Hinton mentioned Daniels pitching with bone chips in his arm, always in pain. His loss of effectiveness worried Daniels to the point that his hair started to fall out. In 1979 he recalled, “I was worried about getting my five years in for the pension.”28 Continuing to alternate between the starting and bullpen roles, Daniels ended the 1962 season 7-16 after his 1-10 start. The Senators finished last. After the season Rollie Hemsley, who had been fired as a coach after the season ended, said, “They pitched (Daniels) 12 times with a sore arm. He never knew whether he was a starter or a reliever. Bennie needed a little help.”29

Over the next three seasons, Daniels turned in mediocre records: 5-10, 8-10, and 5-13. He flashed occasional brilliance: a two-hit shutout of Minnesota in 1963, two shutouts of the Chicago White Sox in 1964 that knocked them out of the pennant race. Bob Addie, writing for the Washington Post, observed, “Daniels baffled his bosses with his often brilliant and then mediocre performances.”30 By the end of the 1965 season, general manager George Selkirk and manager Gil Hodges had given up on Daniels. Selkirk sold Daniels to the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League with the understanding that if Daniels turned his game around he would be brought back.31 It was not to be. After pitching ineffectively, his arm not getting any better, Daniels decided it was time to hang it up and retired from the game. For Hawaii in 1966, he was 8-15 with a 5.51 ERA.

Leaving the game was a shock. Daniels was among those second-generation African Americans who, once their playing days were over, found there was no place for them in the game. Jules Tygiel in Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy illustrated this point. In 1964 just before Daniels left the game, only two blacks were full-time coaches in the majors. Chances for employment in the minors were just as rare. 32

Daniels took on all sorts of jobs to support his family. Over the next few years he worked for the California Department of Motor Vehicles, was an aircraft tool estimator, sold insurance, anything to get along. Then two jobs came up. One was with the state giving clinics for youth baseball coaches. He enjoyed teaching the game to people who were working with youngsters. Then funding for the program ended. Daniels next obtained a job at Martin Luther King Jr. Hospital, first as a traffic hazard inspector, community liaison man and finally CETA (Comprehensive Employee Training Act) coordinator for the hospital.33 He served in that position for nearly ten years when his life took a self-inflicted turn for the worse.

In 1977 Daniels was arrested on charges of misappropriating $107,000 in public funds between 1974 and 1977. He pleaded no contest. According to the prosecution, “ For employees who were no longer employed under CETA, Daniels would continue to receive checks in their names. He was forging time cards that were submitted to the county auditor’s office, which would process the checks back to him. He was endorsing and receiving the face value of the checks. We presented over 500 warrants – or county checks – he had endorsed.”34 He was sentenced to one the three years in prison.

About six months later Daniels spoke with Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post in an interview at the California Institute for Men at Chino, California, where Daniels was serving his sentence. “I did it. I was wrong. But I’m not ashamed,” Daniels said.

While Daniels was a counselor for CETA, his function in part was to work with young men to enable them to get jobs. Once a trainee moved on to a job, Daniels kept his time card active, forging the trainee’s name, cashing checks, and paying another young person with the cash. Daniels could have claimed his actions were driven by the highest of motives – helping others –but he did not take that route. “That isn’t quite right. I did things that were wrong. If you did something that’s wrong, like I did, you pay for it. You don’t fight the system.”35

Explanations of what had taken place given, Daniels focused on the future. His wife, Sue, and children visited him at Chino each weekend. Their visits kept up his spirits. He felt that once he served his time he could rebound with little difficulty. “After what my wife and I have been through, in the minors, then after I quit baseball, we’re used to starting over fresh,” he said. “This time won’t be the worst.”36

Daniels was right: He rebounded, steering straight. After finishing his term at Chino, he soon obtained a job with a veteran’s hospital as a scheduling clerk. He held that position for 15 years before retiring in December 1997.37 After retiring, he made the rounds of sports card collector shows, signing autographs.

As of December 2012 Daniels, 80, and his wife of 56 years, Sue, lived in Compton. He politely declined to be interviewed for this article. Daniels has led a demanding life. Starting from a sickly childhood as the son of a farmer from the Deep South, he progressed through the minor-league system to the majors when it was hard for blacks to succeed. After baseball ended, new challenges ensued: finding a steady job, time spent at Chino and practically starting all over again as he neared 50.

A life of adversity, some of it self-inflicted, of achievement, but mostly one of perseverance.

Last revised: September 3, 2014

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Notes

1 http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=1940usfedcen&indiv=try&h=65867544.

2 “Daniels follows ’56 Script in Fast Start at Hollywood,” The Sporting News, May 29, 1957.

3 http://www.baseball-reference.com /bullpen/Bennie_Daniels.

4 “Daniels follows…” The Sporting News, May 29, 1957, 29.

5 “From Service Front,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1954, 23.

6 Daniels’ file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

7 “Daniels career blossomed with Senators during 1961,” Sports Collectors Digest, May 26, 2000, 28.

8 “Daniels follows…” The Sporting News, May 29, 1957, 29.

9 “Daniels career…” Sports Collectors Digest, May 26, 2000, 28.

10 Ibid.

11 “Bunts and Boots,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1958, 31.

12 “Six Rookies Rated Spring Surprises,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1958, 15.

13 “Daniels’ Fast One Busts Rival Hitters’ Hearts, Catcher’s Finger,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1958, 31

14 Lester J. Biederman, “Cardinals Playing Livelier Ball Since Hemus Affair Here,” Pittsburgh Press, May 21, 1959.

15 “Hemus Plunked, Lets Bat Sail in Fracas With Bucs,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1958, 23.

16 Jim Brosnan, The Long Season: The Classic Chronicle of Life in the Majors (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960; reprinted by Penguin Books, 1983), 115-116.

17 David Halberstam, October 1964 (New York: Villard Books, 1994), 108-109.

18 “Daniels Figures High in Pirates Plans,” Los Angeles Sentinel, April 7, 1960, B9.

19“Who Won Series? Tax Collectors Net Top Take, 346 Gs” The Sporting News, November 2, 1960, 10.

20 “Buccos Beef Up Bull Pen in Deal for Lefty Shantz,” The Sporting News, December 28, 1960, 11.

21 Rich Westcott, Mickey Vernon, The Gentleman First Baseman (Philadelphia: Camino Books Inc., 2005), 172.

22 “Bennie Daniels Doesn’t Regret Going from Rock to Hard Place,” Hartford Courant, January 26, 1979, 59.

23 “Bob Addie’s Atoms…,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1962, 25.

24 “JFK Goes All the Way With Nats – as Laotian Prince Cools Heels,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1962, 15.

25 “Twirler Daniels Earns No. 1 Spot on Senator Staff,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1962, 29-30.

26 “Bennie Daniels Pulled Switch as First Winner in New Park,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1962, 27.

27 “Flyhawks Feeble Flailing Leaves Vernon Whipped,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1962, 19, 24.

28 Thomas Boswell, “Daniels in Prison: Nice Guy Gone Wrong,” Washington Post, January 15, 1979.

29 “Hemsley Tosses Barb at Nats for Mound Strategy,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1962, 25.

30 Larry Moffi, Crossing The Line; Black Major Leaguers: 1947-1949 (Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1994), 164-165.

31 “Old Doc Selkirk To Try Hawaiian Cure on Daniels,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1966, 18.

32 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment, Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 338-339.

33 “Bennie Daniels Doesn’t…” Hartford Courant, January 26, 1979, 59.

34 “From Innings Pitched, To Time Served,” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, July 27, 1978, D-4.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Daniels career …” Sports Collectors Digest, May 26, 2000, 28.

Full Name

Bennie Daniels

Born

June 17, 1932 at Tuscaloosa, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.