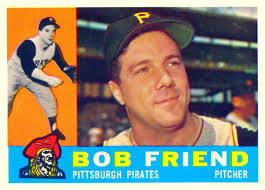

Bob Friend

Bob Friend was one of baseball’s more consistent starting pitchers during his era and a workhorse for the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates. That year the right-hander led the team in games started and innings pitched while posting an 18-12 record and 3.00 earned-run average in a major comeback from a disappointing 1959 campaign.

Bob Friend was one of baseball’s more consistent starting pitchers during his era and a workhorse for the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates. That year the right-hander led the team in games started and innings pitched while posting an 18-12 record and 3.00 earned-run average in a major comeback from a disappointing 1959 campaign.

Durable at 6-feet and 190 pounds, Friend — nicknamed “The Warrior”1 — never spent a single day on a disabled list in his 16-year career, in which he pitched mostly for the Pirates. At the beginning of his career, Friend’s best pitches were a sinking fastball and a hard curveball; later on, he would add a slider to his repertoire. He had unusually good control.

“I had a real good sinker that carried me through most of the prime of my career,” Friend said in an interview. “I also had a hard curve and a fair off-speed pitch, but it was the sinker more than anything else.”2

A winner of 197 major-league games, Friend as of 2018 still held Pirates records for career innings pitched and strikeouts. From 1951 to 1965 he averaged 232 innings pitched and 13 victories for some very lackluster Bucco teams. He pitched more than 200 innings for 11 consecutive seasons (1955 through 1965). As a 24-year-old in 1955, Friend became the first pitcher to lead his league in ERA while pitching for a last-place team. He went on to pace the National League in victories once, innings pitched twice, and games started three times.

Robert Bartmess Friend was born in Lafayette, Indiana, on November 24, 1930. He grew up in nearby West Lafayette, and as a young boy studied piano; his father was an orchestra leader who died when Bob was 16. At West Lafayette High School, Friend was a sports star — an all-state football halfback and an all-state pitcher, and he also played basketball and golf. It was in high school that Friend earned the “Warrior” nickname.

“That came from high-school football,” Friend said. “I was a pretty good tailback, and then later on when I was pitching so many innings, the nickname stuck.”3

Because his father and many other family members had attended Purdue University, a young Friend dreamed of playing college baseball and football there. But a shoulder injury suffered in high school shifted his interests away from football and to baseball.4

He enrolled at Purdue in the fall of 1949, and a year later signed a professional contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates. The scout who inked him to the deal was Stan Feasal, who once worked for Pirates general manager Branch Rickey in Brooklyn. Friend’s bonus was $12,500, a decent amount in those days. The 20-year-old was invited to join the Pirates in spring training in 1950, and afterward was given a minor-league assignment.

During his playing career, Friend kept up his pursuit of a college degree, attending Purdue during baseball offseasons for eight straight years. He eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1957, and was a member of the Sigma Chi fraternity.5

After entering Pittsburgh’s farm system in 1950, Friend posted a 12-9 record for the Waco Pirates in the Class B Big State League. Bumped up to the Indianapolis Indians of the Triple-A American Association, he finished the year with a 2-4 record. Friend told SABR researcher Gregory Wolf in a published interview that he learned about his promotion from Waco manager Al Lopez, the former major-league catcher.

“He was a big influence on me,” said Friend. “In my last game at Waco I pitched a no-hitter and Joe Brown (business manager of the team) called me in and said, ‘You’re going to Indianapolis.’ ”6

Rickey was intent on developing young talent quickly, especially pitching, so he moved Friend onto the major-league roster at the start of 1951. It came as a surprise to Friend. “I really didn’t know that I made the team until Billy Meyer, who was the manager at that time, came up and told me that he liked what he saw and he’d give me a shot,” he told Wolf. 7

Despite the Pirates’ losing ways in the early 1950s, Friend admired Meyer, who had to deal with plenty of Pirate misfortunes on the field. “He was one of the good ones. He was losing his patience with the players they were bringing up. I don’t think he could go through another losing season, especially like the one in 1952 when we lost 112 games,” he said.

Friend’s first season was 1951, and the 20-year-old went 6-10, not getting much run support from a dreadful Pirates team that finished seventh in the eight-team league. He posted a 4.27 ERA and switched off as a starter and a reliever in his rookie year, starting 22 games and relieving in 12.

The next few years were more of the same — a young Friend learned the ropes of pitching on lackluster teams. In 1952 he posted a 7-17 record with a 4.18 ERA; in 1953 he went 8-11 with a 4.90 ERA, and then in 1954 he won seven and lost 12 while putting up a 5.07 ERA. All those Pirate teams finished dead last.

At the end of the 1954 season, some of the Pirate coaches worked with Friend to change his pitching windup so he could be more deceptive with the ball. That way he had a better curveball, and the new windup gave batters a more difficult time, Friend said.8

It helped greatly — his breakout season came in 1955. Friend’s 2.83 ERA was the best in the National League. His 14-9 record was more indicative of the Pirates’ last-place finish and league-worst offense. For the first time — of which there would be many — Friend reached 200 innings pitched. He also struck out 98 batters in 44 games (20 starts), as he continued to alternate between starting and the bullpen.

By now Friend had established himself as Pittsburgh’s best pitcher (there was not much competition). Teammate Vern Law was the second best hurler on the team at that point. In 1955 no Cy Young Award was given out (it began in 1956), but arguably Friend might have won it.

By this time Branch Rickey’s rebuilding effect on the Pirates was well under way. Friend said that Rickey had brought in a lot of his own people — scouts, for example — from the Brooklyn Dodgers, where he had worked before. “His idea was to build an organization like the Brooklyn Dodgers or the St. Louis Cardinals,” Friend said. 9

Friend said the Pirate players both feared and respected Rickey. “They respected him but they were also afraid of him because he was tough on contracts. The way he was sending people in and out of the minors, you didn’t know who would be next.”

When the Pirates traded left-field slugger Ralph Kiner to the Cubs in 1953, however, that did not sit well with Friend or the players and fans. “Ralph was one of the great guys on the team. That was the only person I thought he mistreated. Ralph Kiner kept bringing people into the ballpark. He was a good influence and really missed,” he told Wolf.10

Baseball was changing, and on the labor front, Friend soon got active in what would become the players union. Starting in 1953, he served as the Pirates’ player representative for ten years and as the National League player representative for five years. While a strong advocate of better pensions and benefits for players, he was not in favor of player strikes.11

Friend followed up his 1955 season with another solid one in 1956, where some — not all — of his statistics would improve. Named to the All-Star team for the first time, he went 17-17 with a 3.46 ERA and 166 strikeouts, 68 more than the year before. He pitched an amazing total of 314 innings (league leader) and started 42 games (league leader and the most since Pete Alexander in 1917) in 49 appearances. He had 19 complete games and hurled four shutouts. Meanwhile, the Pirates inched up to a seventh-place finish.

Health problems forced Rickey to retire in 1955, and the Bucs got a new general manager in Joe L. Brown. “Joe was different than Branch Rickey,” Friend said. “He wasn’t going to copy Rickey. Who can? Joe Brown had his own style. He communicated well with the players. They liked Joe and he was fair in contracts.”12

The long-suffering Pirate fans were fair, too. According to Friend, they never gave up on the team despite several rough seasons in a row. “They were pretty good, especially considering how much we lost. How can you be happy with that? The Pirates are an old franchise. They were sophisticated baseball fans and they knew what was going on. They kept coming back and they were loyal,” he said.13

The next season, 1957, Friend, clearly a workhouse on the mound, became a starter exclusively, and he continued to improve. His ERA dipped to 3.38 as he notched a major-league-leading 277 innings. His record was 14-18. The Bucs finished seventh again, tied with the Chicago Cubs.

Finally, in 1958, both Friend and the Pirates put together mutually strong seasons. Pittsburgh slightly ramped up its offense to finish second in the league while Friend won a career-high 22 games (14 losses) with a 3.68 ERA. He won a trip to the All-Star Game, and once again led the league in starts (38) while throwing a hefty 274 innings. His 22 wins were good for a tie for first in the league with Warren Spahn. He made his second All-Star Game and came his closest to winning the Cy Young Award (third place).

Asked what he considered his two biggest career highlights, Friend responded that his 22 wins in 1958 and his durability — perhaps above all — stood out in his mind.

“I was able to pitch every third or fourth day for more than ten years and not miss starts,” he said decades later.14

Looking ahead, both Friend and the Pirates seemed poised for glory.

However, these things sometimes take time. An out-of-shape Friend battled weight problems in 1959, going 8-19 with a 4.03 ERA. He led the league in losses that year. The Pirates fell back to fourth place, though they showed promise with a 78-76 record.15

A determined Friend re-earned his “Warrior” moniker and got into terrific shape that offseason. Though he lost 4-3 on Opening Day (April 12) to the Milwaukee Braves, he rebounded to pitch three complete-game victories in a row. By the end of May, he sported a 2.33 ERA and 5-2 record. In June Friend notched four more victories while keeping his ERA at 2.91. He hurled a complete-game shutout on June 22 against the Cardinals.

Named to the All-Star team for the third time, Friend wobbled a bit in July, going 3-4 en route to a 3.03 ERA and 11-7 record by that point in the season. One big victory came July 25 when he prevailed over St. Louis to put the Pirates in first place for good. He lowered the ERA to 2.95 by the end of August while gaining his 14th victory against 11 losses. He exhibited his best pitching in the all-important September stretch drive, tossing three complete games and winning four of five decisions while the front-running Bucs won his only no-decision start in that span.

Friend elaborated on the 1960 squad in another interview. “The team was a mixture of veterans and young players. We never made too many mistakes and we were a good fielding and pitching team. At the plate, we knew how to spread the ball around.”16

With the Pirates headed to the World Series, Friend finished 1960 with an 18-12 record and a 3.00 ERA. He was named the UPI’s Comeback Player of the Year, and was second in the league in games started (37) and innings pitched (275 2/3), fourth in complete games (16) and fifth in strikeouts with 183, which was a club record. Always an excellent control pitcher, he topped the National League in strikeout-to-walk ratio at 4.07.

In the fall classic the Pirates would be facing a powerful New York Yankee team highlighted by Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Whitey Ford, and Yogi Berra. That season they had won 97 games — only two more, however, than the underdog Pirates.

“We respected the Yankees,” said Friend. “They were a good team, but we beat some good teams in the National League … and came into the World Series in good shape.”17

He said, “We weren’t intimidated going into it. We knew we had a good team, and we had beaten a lot of good teams — the Braves, Cardinals and Dodgers — during the regular season.”18

As has been well chronicled, the insurgent Pirates won one of the most dramatic World Series ever with Bill Mazeroski’s Game Seven home run — plus a whole lot of other help from different players in that 10-9 victory.

But Friend’s performance in the Series was not up to the benchmark he had established during the season. Simply, he got rocked.

He started Game Two and was chased after four innings (though he gave up only two earned runs) as the Yankees pummeled Pittsburgh, 16-3. In his next start, Game Six, Friend caught the brunt of the Yankee attack, surviving only two innings while coughing up five runs in a 12-0 shutout of Pittsburgh. With the Series tied at three apiece, all Bucco hands were on deck for Game Seven; Friend was called in to pitch the ninth inning, but he could not stop the Yankee offense then, either, giving up two runs and not even securing an out.

Overall, Friend went 0-2 with a 13.50 ERA for the World Series — but his team won. Here is how one Associated Press writer summed up manager Danny Murtaugh’s choice of Vern Law — and not Friend — to start three games. “He followed up twice with Bob Friend, who simply didn’t have it but deserved the slot after winning 18 in the pennant race.”19

It sounds as if Murtaugh knew that Friend had been taxed with a heavy pitching load in September in which he had given his total effort — he started six games and threw 38 innings on top of an August when he hurled 56 innings. Arguably, there was probably not much left in his arm come October. And the Yanks were just darn good hitters, of course.

Friend understood what had happened. “I had my best season in 1960, I believe, but did not have a good Series.”20

As he explained to Wolf, “I think I put too much pressure on myself. I expected to have a good Series. I was one of the hottest pitchers coming down the stretch, but didn’t perform well in the World Series. We end up winning, though, and that’s the big thing.”21

To Pittsburgh fans, it did not matter—they were champions! The city went wild after the final game at Forbes Field, which gave the Pirates their first World Series title since 1925.

Years later Friend recalled the pandemonium throughout the Iron City: “We heard that a celebration was going on, so some of us went downtown to see what is was all about. It was pretty wild. I didn’t stay around long. It was really something. … A couple days later they gave us a ticker-tape parade. They were throwing IBM cards from the buildings.”22

The Pirates never did reach those heights again while Friend played for them — the best they would do was third place in 1965, his last season with the organization. In the afterglow of that magical World Series win, he compiled a respectable 3.85 ERA in 1961, but led the league in losses with 19 while winning 14. He hurled 236 innings, the seventh consecutive season he had more than 200. The next season, 1962, he led the league with five shutouts while crafting an 18-14 record and a 3.06 ERA.

Friend tallied one of his best seasons in 1963 when he recorded a career-low ERA of 2.34 en route to winning 17 games (he lost 16). In walking just 44 batters, he topped the league in fewest bases on balls per nine innings (1.5).

His season of 1964 was consistent if not spectacular — 13-18 with a 3.33 ERA — as was the next one, his final season in a Pirates uniform: 8-12 and 3.24 ERA. He made a salary of $37,500 that year, and for 1966 would make $47,000 — the only figures on record for him.23

Some might say Friend’s low ERAs were a result of his home-field environment in spacious Forbes Field. But Friend, like many Pirates, understood that while the park was a hindrance for home-run hitters, it actually proved quite beneficial for singles and doubles and triples — the Pirates enjoyed a high number of batting champions throughout the years. Forbes Field was not unfriendly to run scoring, though it varied like every park year-by-year. In fact, it was about average league-wise during Friend’s tenure, according to Baseball-Reference park factors.24

Friend said, “I was never concerned about the long ball like you would in Chicago or Brooklyn. I got to the point that if I kept the ball down and had good control, I’d do well. I liked Forbes Field. A lot of the guys would try not to hit the long ball at Forbes Field and became better hitters. That was our team, too. We didn’t hit a lot of home runs, but we knew how to hit. We’d spray the ball around and that’d drive opponents nuts.”25

But Forbes Field no longer was Friend’s home come the winter of 1965-66. The Pirates traded him to the Yankees for reliever Pete Mikkelsen. In his last season in professional baseball, Friend went 6-12 with a 4.55 ERA. During the season, the Mets purchased Friend for cash, and he played his final game with New York’s National League team on September 24, 1966. Afterward, the 35-year-old Friend retired from baseball.

“At age 35 and with the Mets rebuilding, Seaver and others were starting to come up. They had a plethora of pitching prospects in their organization. It wasn’t a big surprise,” Friend recalled.26

Bob Friend finished his 16-year career with a 197-230 record, a 3.58 ERA, 1,734 career strikeouts, and 3,611 innings pitched. He pitched 36 shutouts in 163 complete games. In 602 games, he gave up 1,438 earned runs. Friend remains as of 2012 the only pitcher to lose more than 200 while winning fewer than 200, mostly due to playing with five last-place Pirate teams. On the sabermetric front, he had a career Wins-Above-Replacement total of 42.1.

As a batter, Friend hit .121 with two home runs and 60 RBIs, three coming on May 2, 1954, in an 18-10 win over the Chicago Cubs.

Off the field, Friend in 1957 married Patricia Koval, a nurse in the office of the Pirates’ team doctor. They had two children — one of them, Bob Jr., turned out to be a highly successful professional golfer on the PGA Tour.

After retiring from baseball, Friend worked as an insurance broker and served as Allegheny County controller from 1967 to 1975. (He ran at the urging of Pirates co-owner Tim Johnson.) He also played a lot of squash and sang in a barbershop quartet. But perhaps his consuming retirement passion was golf — he sported a 6 handicap, and a Sports Illustrated article in 2004 described Friend as a “golfaholic” who had played most of the great courses in the game. 27

On the political front, when he won his first election — it was a tight race — Friend said it was like coming into the ninth inning, “but there was no Elroy Face in the bullpen.”

He elaborated: “You don’t have as much control over the results of an election as you do a ballgame. Here you go all out and meet the public and they decide the outcome.” He believed that simply being a well-known ballplayer was not a big advantage.28

“It’s one thing to be a ballplayer, but so what?” Friend said, adding that sometimes he spent 20 hours a day campaigning. “I went to 40 mill gates and talked to workers. Politics is a good competitive game now that I’m out of baseball.” 29

He added, “I had a wife who was a good campaigner, and I’m thankful for that.” 30

Re-elected as controller in 1971, Friend went on to serve as a three-time delegate to the Republican National Convention, but did not run for higher office beyond controller. On the philanthropy front, he led a popular annual fundraising drive for Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh in the 1980s.

“Friend wages an annual letter campaign urging friends and business acquaintances to look deep into their hearts and dig deep into their pockets to help patients who otherwise would not have the means to pay for medical care,” a writer for the Pittsburgh Press remarked.31

Friend retired from his post-baseball business and political career in 2005 and lived in O’Hara Township, northeast of downtown Pittsburgh, until his death at the age of 88 on February 3, 2019. Bob Friend, “The Warrior,” is considered one of the Pirates’ most historically significant pitchers of all time.

An earlier version of this biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Rick Cushing, 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates: Day by Day: A Special Season, An Extraordinary World Series (Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing, 2010), 363.

2 Clifton B. Parker interview of Bob Friend, November 17, 2012.

3 Ibid.

4 Bob Friend Wikipedia entry, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Friend

5 Ibid.

6 SABR member Gregory Wolf’s oral interview of Bob Friend found at hardballtimes.com, April 6, 2012, “A Friend of Pirates History.”

7 Ibid.

8 Rick Cushing, 363.

9 Wolf interview.

10 Ibid.

11 Rick Cushing, 364 and Bob Friend Wikipedia entry at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Friend

12 Wolf interview.

13 Ibid.

14 Parker interview.

15 Baseball-reference.com entry at http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Bob_Friend.

16 Parker interview.

17 Wolf interview.

18 Parker interview.

19 Associated Press article in the Miami News, “Pirate Victory Like Pep K.O. Over Rocky,” October 16, 1960.

20 Parker interview.

21 Wolf interview.

22 Rick Cushing, 364.

23 Bob Friend Wikipedia entry.

24 Pittsburgh Pirates Attendance, Stadiums and Park Factors, at http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PIT/attend.shtml

25 Wolf interview.

26 Ibid.

27 Bill Syken, “Bob Friend, Pitcher,” Sports Illustrated, August 9, 2004.

28 Associated Press story in the Daytona Beach (Florida) Morning Journal, “Bob Friend Elected on the First Try,” November 9, 1967.

29 Ibid.

30 Parker interview.

31 “Ex-Pirate Pitcher Proves He’s Hospital’s Best Friend,” Pittsburgh Press, November 17, 1981.

Full Name

Robert Bartmess Friend

Born

November 24, 1930 at Lafayette, IN (USA)

Died

February 3, 2019 at O'Hara Township, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.