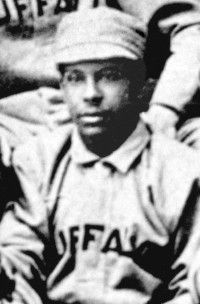

Frank Grant

Frank Grant was one of the best second basemen of the nineteenth century. His name may not sound familiar to most because he was African American. Consequently, he toiled for black clubs and briefly in the white minors before the color line was firmly entrenched. He was dubbed the “Black Dunlap,” a reference to his skills in the field that matched the popular white second baseman Fred Dunlap –both had great range, quick hands and a strong arm – with the word “black” thrown in so no one forgot that he was not white. Others though called him an Indian, a Spaniard, an Italian, a Brunette, Darky, Dusky, Coon or an array of even harsher terms.

Frank Grant was one of the best second basemen of the nineteenth century. His name may not sound familiar to most because he was African American. Consequently, he toiled for black clubs and briefly in the white minors before the color line was firmly entrenched. He was dubbed the “Black Dunlap,” a reference to his skills in the field that matched the popular white second baseman Fred Dunlap –both had great range, quick hands and a strong arm – with the word “black” thrown in so no one forgot that he was not white. Others though called him an Indian, a Spaniard, an Italian, a Brunette, Darky, Dusky, Coon or an array of even harsher terms.

He was the best black player of the century, with the glove and with the bat. In today’s vernacular, he was a power hitter, often leading his team and league in slugging and extra-base hits. He could also fly, stealing numerous bases and covering more ground in the infield than perhaps anyone of his era, white or black. In fact, one big league manager complained that his excessive roving to his left and right and into the outfield would not be allowed in the majors. As one of Grant’s contemporaries, Sol White, put it, “Frank Grant…in those days, was the baseball marvel. His playing was a revelation to his fellow teammates, as well as the spectators. In hitting he ranked with the best and his fielding bordered on the impossible. Grant was a born ballplayer.”

He was the only black player before the 1940s to play three consecutive seasons with one club in Organized Baseball: From 1886-1888, he played for Buffalo, a team that played in a top minor league. Each year he led Buffalo in hitting and slugging. In total he played four years in the top minors. Nevertheless, he was never considered for a major league roster spot, despite the fact that numerous Buffalo teammates with lesser all-around skills found such jobs. Despite his lack of major league experience, Grant was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, in 2006, one of the few pre-Negro League players so honored.

Ulysses Franklin Grant was born on August 1, 1865, in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, in the town of Pittsfield, the first known location in the United States that baseball was played (in 1791), though bat and ball games have been played for centuries. He was called Frank his entire life.

His parents, Franklin Grant and Frances Hoose Grant, were Massachusetts natives. Franklin was about 15 years older than Frances. They met in Pittsfield, Frances’ native town and perhaps Franklin’s as well. The 1850 U.S. Census shows both of them residing in the community. Franklin, 33 years old, was a farm laborer and Frances, 18, lived apart from her family presumably in employment of another. Franklin is listed as mulatto,” Frances as “black,” but her family is denoted as “mulatto.” (At various times the family was listed as mulatto and black. Frank had a light complexion.) The couple was married shortly after the Census, having their first child circa 1853.

The family moved around Berkshire County. The 1860 Census shows them living in Dalton, about five miles from Pittsfield. Franklin passed away four months after Frank’s birth, from an internal infection at age 48. The family moved to Williamstown, a little over 20 miles from Pittsfield and Dalton, at some point, perhaps as a consequence of Franklin’s death. They resided there by 1870 at the latest when Frank was three, as seen in the Census that year, and remained in the area, living on Spring Street not far from Williams College. (The exact location of the home is not known but a marker was placed in the general vicinity, on current college property.) Frances worked for her neighbors the Perrys, whose patriarch was a professor at the college, and also a “restaurant keeper.” Her older daughters were waitresses, presumably at the same establishment or household.

Frank was the ninth child as best can be determined. His siblings included: Catherine Amelia, born circa 1853; Charlotte, circa 1854; Harriet (Nellie), circa 1856; Willis W., circa 1856; Katie, circa 1858; Walter, circa 1859; Clarence, circa 1862; and Lucy, circa 1864. Walter and Lucy may have died young. Also, Walter and Clarence may have been one and the same, as the Censuses are a bit confusing. Clarence, three or four years older than Frank, played professional baseball as well – with a top black team, the Cuban Giants.

Frank grew up playing ball with his older brother Clarence. They played mostly with local white kids. Frank was known among the boys for doing tricks with the ball, such as catching it behind his back and popping it off the ground and into his hands with his feet. One of the Perry children, Bliss, later editor of The Atlantic at the onset of the twentieth century, was a teammate. The following passage is from his autobiography, And Gladly Teach, found in the work of baseball historian John Thorn, “In the woods and fields I was perfectly happy, and also when I was playing ball. I had been chosen captain of a nine, at twelve. Two of the players, Clarence and Frank Grant, were colored boys, sons of our ‘hired girl’…Rob Pettit, our left fielder, afterward played for Chicago and went around the world with Pop Anson’s team. We called ourselves the ‘Rough and Readys’” Perry based a character in one of his works, The Plated City, on Frank Grant. The story, as Thorn noted, is similar to and predates the attempt by John McGraw to pass off another black second baseman, Charlie Grant, as an American Indian in 1901 in hopes of including him on his major league roster.

The Grants and Perry also played football, probably a variation of the “Boston Game” that was popular with area colleges, and hence locals. A measurement in 1888 placed Frank Grant, a righthander, at 5’7.5” and 155 pounds. He had a stocky build, as noted by a quote found by black baseball historian Dr. James Brunson, “The colored second baseman, of the Buffalo’s is immense, when he lays aside the team uniform.” The Baltimore Sun in 1890 declared, “He is of medium height, heavy set, but active as a cat.” Grant played ball in high school, which local researchers believe was Williamstown High School.

According to the Sporting Life, Grant’s first baseball team of consequence was a semi-pro outfit from Pittsfield called the Graylocks in 1884, at age 18 or 19. He was the team’s pitcher. More likely it was the “Greylocks” of Williamstown or nearby Adams or North Adams, a nine named for the highest point in Massachusetts, Mount Greylock, located nearby in the Taconic Mountain range.

In 1885, he joined the Plattsburgh (Clinton County, New York) Nameless, a team that straddled the fine line between semi-pro and professional, as a catcher – and played without a mask. The squad entertained vacationers, among others, in the Adirondacks, a popular summer destination. The Nameless predominantly played local nines in Clinton, Essex and Franklin counties, such as, Plattsburgh Williams, Ogdensburg Stars, Burlington Starlights, Port Henry Witherbees, Fort Edward Stars, Rouses Point Beaverwycks, Chazy Clintons and Ticonderoga Stars and even traveling clubs like the Troy Buffalos. One oral story of his time with Plattsburgh highlights his aggressiveness chasing batted balls. One day, while catching, he climbed a telegraph pole and nabbed a foul ball before it floated out of play. The season culminated with a tournament at the Franklin County Fair in Malone. According to the Plattsburgh Sentinel, “The Nameless of Plattsburgh had a ‘walk over’ at the Malone Fairgrounds yesterday [October 1], winning the purse of $100 in a score of 24 to 1 in a game with the Stars of Ogdensburg.”

In 1886 at the age of 20, Grant joined his first professional club, Meriden (Connecticut) of the Eastern League. It was his first club in Organized Baseball. He would in fact play his entire career on the east coast. The Eastern League contained two other black players that season, George Stovey with Jersey City and Fleet Walker with Waterbury. After Grant’s first game for the club on April 14, an exhibition vs. Trinity College, a 22-0 blowout, the Sporting Life stated, “Grant is our young colored player and his home run hit was the longest ever made on our [Meriden] grounds.” Relating to the April 21 game, the weekly noted, “Grant was again called to the box and proved that he can play any position in good shape.”

He appeared in 44 games for the club at second base and pitcher, hitting .316 and posting a 0-1 record in one start, three games pitched; he proved to be the star of the nine, the only regular batting over .277. At the end of May, the Newark correspondent to the Sporting Life mentioned, “The Meridens seem to contain some really good material, but lack the proper coaching. Grant…received frequent and deserved applause for his neat playing [in a game with Newark].”

A bigger problem for Meriden was that it was the smallest city in the league, and consequently the weakest financially. Team officials complained loudly at the beginning of the season that the schedule committee slighted them. They had no weekend dates during May and only seven home games that month. Both were a financial hardship for the club at the onset of the season when revenues were most needed. Probably not coincidentally, Meriden disbanded on July 13, with a poor 12-34 record. Grant and teammates Steve Dunn and Jack Remsen, both former major leaguers, joined the Buffalo Bisons of the International League, playing their first game for the new club on July 14. Buffalo played at the new Olympic Park at the intersection of Richmond and Summer Streets.

Grant was happy to join a wealthier club, as the Hartford Courant noted, “Grant gets double the pay in Buffalo he received in Meriden.” However, his race became more of an issue: St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “The Spaniard is what Grant, the colored player of the Buffalos, is called.” Also the Syracuse Evening Herald recalled, “Manager [John] Chapman of Buffalo calls Grant, his colored second baseman, an ‘Italian.’”

Grant took over second base for Buffalo and pitched a little as well. After a game on July 29 versus Oswego, a 4-2 victory, the Sporting Life noted, “Grant…went into the box [in relief] and pitched a good game, keeping the hits well scattered.” The weekly had further praise in August: “The second-base play of Buffalo’s colored lad, Grant, is described as wonderful. Some of his stops and catches are said to be phenomenal, and withal he plays a steady game, keeping his good work up day after day.” On September 7, he notched ten assists in nine innings.

Buffalo finished in fifth place with a 50-45 record. Grant hit .344 in 49 games, third highest total in the league, and was reserved at the end of the season. He joined the club for spring training and immediately faced the ire of his teammates. Several of the white players refused to sit for the team portrait if Grant was included. Chapman though was able to sooth egos and got the men before the camera. The incident or others like it prompted the Sporting Life’s inquiry, “How far will this mania for engaging colored players go?”

The exhibition season in 1887 kicked off on April 1. Buffalo played Pittsburgh of the National League, an 11-1 romp by the major league club. Regardless, the New York Times claimed, “The feature of the game was the brilliant work of Grant… He had eleven chances, and accepted them all. His batting was also heavy.” Pittsburgh’s manager, Horace Phillips, saw it another way. In the Rochester Union he claimed that Buffalo coddled their star Grant, allowing him to freely wander about the field encroaching on other fielders. As he declared, “The fact remains that in the actual playing of second base he is decidedly crude, and in four cases out of five the player who starts for second with Grant on the base, no matter how good the throw, will reach it.” This is a reference to Grant shying away from the impeding sliding spikes of white players, a criticism heard more than once. However, at this point, Phillips had probably only seen Grant play a couple of times at most and may have had an axe to grind. In the field that day with Pittsburgh was Tom Brown, who claimed that Grant was one of the best second basemen of the century (quote located at the end of this biography).

After a game with the Baltimore Orioles of the major American Association, St. Louis Globe-Democrat quoted a Baltimore newspaper: “The Baltimore American says that it may be considered as assured that the leading second baseman of the International League this season will be the colored man Grant of the Buffalos. He is one of the most active men ever seen, and his plays are quick and precise.” Later in the month, the Sporting Life noted, “The second base play of the colored lad Grant is winning commendation wherever Buffalo goes.” The weekly later illustrated, “Grant, the India rubber second baseman on the Bisons, is a circus all by himself, and a good one.”

On April 16, Buffalo played the Philadelphia Phillies of the National League. Philly won but Grant homered off Ed Daily, who had registered 42 wins for the Phillies the two previous seasons. According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “The Philadelphia boys gave Daily the laugh when the Negro boy, Grant, hit him over the fence for four bases.” After a subsequent 12-8 loss to the Cuban Giants, the Sporting Life commented, “Grant, as usual, distinguished himself at second base for Buffalo.” On Memorial Day, Grant hit for the cycle. In another contest he stole home twice. On June 26, the Brooklyn Eagle reported, “The Buffalo club recently lost two games through the poor play of [James] Purvis, [John] Galligan and Grant, all three of whom had previously indulged in liquor.” Grant, a first-time offender, was fined $10.

Racism reared its head, most prominently in the International League. The pivotal year in the exclusion of African-Americans from Organized Baseball proved to be 1887. The International League formally banned any additional signings of African-American players on July 14. Specifically, a vote taken by club owners directed the league secretary to “approve of no more contracts with colored men.” Officials were reacting to white players’ grumblings and derogatory comments by the press suggesting that the International League change its classification to “colored league.” After the effective banning, the Newark Daily Journal headlined, “Color Line Drawn in Baseball.” Stovey, Frank Grant, Bob Higgins and Fleet Walker were permitted to play out the season in the International League. Walker actually remained in the league through 1889.

The vote was sparked by a revolt in the Binghamton club against black players Bud Fowler and William Renfro. After the contest on June 27, one of Binghamton’s white players, Buck West, rallied the rest of the team around his cause. A petition was inked by nine players and a telegram was sent to the club directors demanding that Fowler and Renfro be released or the protestors would strike. Fed up with the abuse, Fowler asked for his release on June 30 and it was granted. Renfro was later released. One local newspaper, as noted by researcher Neil Sullivan, gave a curt notice to the fans, “Gone coons – Fowler and Renfroe [sic].”

It wasn’t only teammates that had it in for the black players. An unnamed International League player gave a revealing interview to The Sporting News two years later: “Fowler [and Frank Grant] used to play second base with the lower part of his legs encased in wooden guards. He knew that about every player that came down to second base on a steal had it in for him and would, if possible, throw the spikes into him…[Also] about half the pitchers try their best to hit these colored players when [they’re] at the bat.” (The wooden guards of Fowler and Grant were the first instances on the baseball diamond of shin guards.) Similarly, Ned Williamson later gave an extensive interview claiming that the feet-first slide took hold in the game based on contempt for black players (citation found at the end of this biography).

Furthermore, league umpire Billy Hoover admitted to calling close plays against clubs that fielded black players. Part of the shame in the situation arose from the success black players had in the league. Besides Grant’s impressive statistics and accomplishments, George Stovey led the league in wins, Bud Fowler registered a .350-batting average, and Bob Higgins won 19 games.

On the same day as the vote was taken by the directors of the International League, July 14, the most famous and, perhaps, defining racial incident in baseball history occurred. Cap Anson and his Chicago White Stockings refused to take the field in an exhibition game against Newark if the latter team planned to use their black battery, Stovey and Fleet Walker. Newark backed down and pulled Stovey from the lineup. Anson had tried a similar tactic unsuccessfully against Walker in August 1883, but his Toledo team stood up to the Chicago manager.

Buffalo needed Grant. Not only was he the most complete player on the squad, but as the Buffalo Express acknowledged he was the most popular man on the club with the fans. Personally, Grant was a quiet, modest and unassuming man. He never argued on the diamond, at times participating in friendly, competitive banter. A New York newspaper gave a glimpse of his personality: “He electrified Broadway recently by appearing in a blue corduroy coat, black and white striped trousers, yellow gloves, patent leather shoes with light drab gaiters, a slate colored fedora hat and a gold-headed cane.” The Boston Globe noted his appeal in the black community, acknowledging that Grant attracted “a large attendance of gentlemen of color, and not a few dusky dames.”

Nevertheless, the racial reverberations sparked this St. Louis Globe-Democrat quote: “Buffalo is after a new second baseman to take the place of Grant, the ‘Black Dunlap.’” He stayed with the club though. Even in racially tolerant Toronto Grant faced hostilities. According to the Toronto World in respect to the July 27, 1887 game, the Toronto fans broke out into a chorus of “Kill the Nigger.”

On August 27 at Olympic Park, Grant knocked twelve total bases against Toronto in six at bats: grand slam; two-run homer; two-run triple; single. In total he drove in eight runs against Ed “Cannonball” Crane. Toronto, however, scored ten times in the ninth to claim a 26-19 victory. Buffalo finished in second place with a 63-40 record, three games behind Toronto. Buffalo pitcher Mike Walsh posted a 27-9 record to lead the club. Grant batted .353 in 105 games, stole 40 bases and led the league with 11 homers.

Grant re-signed with the club and was once again placed on the reserve list. However, it was still up in the air if the league would allow him to return. On November 16 in Toronto, International League officials met and formed a new league, now called the International Association. According to the Syracuse Evening Herald, “The wire pulling has been all along engineered by Buffalo and Syracuse directors.” The reason for the reshuffling was given as financial in nature. The second day of the meeting offered perhaps another reason. As the Syracuse Standard put it, “Syracuse and Buffalo succeeded in their scheme of having colored players in the league…As the Toronto people forgot to bring up the matter of colored players, they are now kicking themselves.” Offers were immediately mailed out to the black players and three were signed for 1888.

Bob Higgins and Fleet Walker also returned to the league, with Syracuse. Grant opened a restaurant/saloon in Buffalo in September and spent the winter there. Within two months though, he quit the bar business. One report over the winter claimed that he would soon marry Hattie East of Washington D.C. Grant, however, insisted he had no such intentions.

Eighteen Eighty-Eight started off shaky and never really steadied. Grant held out at the beginning of the season, demanding a $250 a month salary. He faced a tough challenge here as the St. Louis Globe-Democrat surmised, “The Buffalo team is probably the cheapest team in the country. Manager Chapman says the high-salaried clubs have been working all season [1887] for the players, the hotels and the railroads, while the clubs have lost money. Probably no man on the Buffalo team gets over $200. Few of them are paid $150 a month and several only $100.” Buffalo finally agreed to Grant’s terms but when he came down with a sore arm at midseason, they cut his pay. Also, the team portrait issue was revisited. None was taken in fact, according to one teammate, “on account of the nigger.”

Grant played some games in the outfield in 1888 to avoid the sliding spikes of white players. The Louisville Post described his plight in the white minors: “He is a fine ball tosser…and hasn’t many superiors among players either white or black…Grant is very popular in Buffalo, and for that reason the management is forced to hold him, although the players of the club are said to feel keenly having to play with a colored man. In the east Grant goes with the other members of the club, stops at the same hotels, eats at the same table and possibly occupies the same room. While in this city he is registered at the Galt House, but is roomed with the colored help and takes his meals with them.”

Grant ran into a wall in July. First, he injured his arm and missed some games. Second, as the Sporting Life illustrated, “Grant has been fined $25 and laid off by Buffalo [for excessive drinking, along with two other teammates], much to the satisfaction of the club members, who dislike the man, and Dame Rumor says that they swear they won’t play good ball until the colored man is fired.” This is a reference to tanking games if he’s in the lineup. Moreover, the Syracuse Sunday Herald noted, “Grant…is in disgrace, smarting under a suspension and a twenty-five-dollar fine. There is considerable feeling in the club against him, and it is said that a determined effort will be made to freeze him out. Some time ago the men would not have a photo taken if Grant was in the group.” Soon thereafter, the Sporting Life announced, “Buffalo is trying to sell Grant’s release to the colored Keystone club of Pittsburg.”

Grant finished the season with Buffalo, but neither he nor his teammates were happy. He hit .346 in 84 games for the sixth-place club. He was reserved over the winter, and club management made several public statements that seemed to indicate they wanted him back. The players though had other ideas in the spring: Yenowine’s News, “The Buffalo players are kicking over playing with Mascot Grant, the colored second baseman.” Per the Sporting Life, “The Buffalo players threaten to strike if Grant, the colored player, returns to the team.”

Grant was holding out. He wanted to be bumped back to $250 a month, or perhaps more likely he had enough of his Buffalo teammates. By February, he joined the Cuban Giants, his first black club, which spent the winter based at the Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine, Florida. The men also doubled as waiters at the hotel. The Giants spent many winters at the hotel. During these stints in Florida, Grant and the Giants may have sailed to Cuba for games.

According to The Sporting News in mid April 1889, “Grant played with the Cuban Giants in Washington yesterday, and in reply to an inquiry said he would sign [with Buffalo] only for $250 a month. This is considered too high, and the other members of the team threaten to rebel if he plays. Last year they refused to have their picture taken on Grant’s account and objected to traveling with him. The boys acknowledge that he is a good player, but they are in rebellion just the same. Their sentiment is that colored men should not play with white men.” The $250 was apparently too much in 1889 even though that was his starting salary in ’88. The white players won out. Buffalo let their leading hitter go and regretted it. At the end of the season, the Buffalo correspondent to the Sporting Life opined, “The dreary and disastrous season ended for Buffalo,” a city that as of 1885 fielded a major league club. In 1890 the team transferred to Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The New York Age hailed Grant’s arrival with the Cuban Giants: “The new acquisition, Grant of the Buffalos, is an excellent player and though on second base he plays almost the whole infield. He is a sure catcher and a reliable batter.” The Age continued in May, “Grant, the second baseman from Buffalo, is a clever player and worked hard to win. He is a sure batter, a nice slider and a sprinter.” The Syracuse Herald seconded, “Frank Grant, formerly of the Bisons, is playing great second base for the Cuban Giants.”

The Cuban Giants were the first top black team in baseball history. They were formed in 1885 by Frank P. Thompson who melded three teams – Philadelphia Keystone Athletics, Washington Manhattans and Philadelphia Orions – and renamed them the Cuban Giants. At the time Thompson, an African-American, was based in Babylon, Long Island, where he was the headwaiter at the Argyle Hotel. He initially bought the Keystone Athletics and relocated them to Babylon to entertain guests at the hotel. Thompson’s hospitality skills were in demand throughout the east coast. In the winters, he worked in St. Augustine, Florida, at the Ponce de Leon Hotel; in the summers, he toiled at northern vacation or otherwise popular spots.

In 1886, Thompson sold the Giants and the club landed at the Chambersburg Grounds in Trenton, owned by Walter Cook, a wealthy, white local. John M. Bright purchased the club in June 1887. The Sporting News surprisingly posted this bit of praise: “There are players among these colored men that are equal to any white players in the ball field. If you don’t think so, go out and see the Cuban Giants play.” By 1887, the Giants were renting space at the Polo Grounds and in Brooklyn and Hoboken, New Jersey. They were aggressively, and successfully, marketing themselves throughout the area.

In 1889, the Cuban Giants joined the Middle States League representing Trenton. Besides Grant, ace lefty George Stovey also joined the club. Grant was named captain. At the end of July the Philadelphia team left the league and was replaced by the New York Gorhams, another black club, now representing Easton, Pennsylvania (though the club based itself out of Harrisburg). Following the July 7 game, the Trenton Times commented, “Too much praise cannot be bestowed on the work of the Cuban Giants. None of the major league teams play a prettier game than this club. The Giants have in Grant one of the best second basemen in the country. In the ninth inning [a high-liner was sent] towards right which looked good for two-bases, but Grant jumped into the air and pulled it down with one hand. For a few seconds the spectators were spellbound and when they realized what he had done, Grant was cheered to the echo.”

In July and August the Cuban Giants and Gorhams pooled their teams to form another dubbed the Colored All-Americans that barnstormed in upper New York State mainly on weekends. The team was fluid, players moving back and forth between the All-Americans and their regular squad, as both parent clubs still maintained their presence in the Middle States League. Grant played at times for the Colored All-Americans. Trenton finished in second place, behind Harrisburg, with a 55-17 record. Grant, playing second, third and catching, batted .313 in 67 games.

In the spring of 1890 Grant, now 24 years old, was again named captain of the Cuban Giants. The Washington Post declared, “They are stronger this year than ever before, having added Grant, the great second baseman, and [Fleet] Walker, the catcher, to their ranks.” Grant’s brother Clarence also joined the club. The Cuban Giants applied to the Eastern Interstate League (the revamped Middle States League) in March seeking to join the league as a second representative from Harrisburg, as had been done the previous season when Easton was also essentially based in Harrisburg. They were rejected. The Giants then contacted interests in York, Pennsylvania, and secured a berth there in the same league, becoming officially known as the York Monarchs.

Harrisburg’s manager [James] Farrington was irate that the Giants, tough competition, were once again brought into the league. He countered by signing their catcher Clarence Williams and then landed Frank Grant. York filed a protest with the league and sued, as Grant had in truth signed contracts with both clubs. Grant joined Harrisburg while the court case was pending.

He arrived with Harrisburg to a hero’s welcome on May 5 before his first game with the club. He appeared in a carriage pulled by a locally famous trotting horse. As the Harrisburg Morning Patriot highlighted, “Long before it was time for the game to begin, it was whispered around the crowd that Grant would arrive on the 3:20 train and play third base. Everybody was anxious to see him come and there was a general stretch of necks towards the new bridge, all being eager to get a sight at the most famous colored ballplayer in the business…When he appeared on the field a great shout went up from the immense crowd to receive him, in recognition of which he politely raised his cap.”

He did well from the beginning, as the Sporting Life mentioned after the May 7 game against Altoona, “The feature of the game was Grant’s remarkable fielding, he assisting in two lightning double plays.” On June 7, Judge Simonton of Harrisburg refused to grant York’s injunction.

Harrisburg was the financially strongest club in the Eastern Interstate League and, as such, was looking to move into a higher league. The opportunity arose in mid July when Jersey City folded (unable to meet its payroll) in the Atlantic Association (AA), a higher minor league. Harrisburg applied for admission. The AA president attended a local game and liked the strong turnout and potential of the city. One problem existed though. The AA had no black players, and many within the league didn’t want any.

According to the Washington Post, “The Association at its meeting [July 17] passed a resolution to admit Harrisburg, providing it would release the two colored men.” Per the Sporting Life, “The only objection to Harrisburg’s admission was the fact that two colored players were members of the team. It was made a condition of admission that these colored men be released, but this Harrisburg declined to do.” Moreover, from the Baltimore Sun, “While it is not a rule of the Association to forbid the employment of colored players, it was a mutual understanding…Manager [Billy] Barnie, of Baltimore, wires that Grant cannot play in Baltimore with Harrisburg, but his club will play in Harrisburg with Grant in the home team…The Harrisburg management radically objects to losing the services of its best player.”

Harrisburg stood firm and should be commended, in part. They insisted on keeping Grant, and won the battle, but released Clarence Williams as a peace offering. Without Harrisburg the Eastern Interstate League collapsed. York finished with the best record, but Harrisburg was awarded the championship. Grant appeared in 59 games in the league, batting .333.

Some of the AA clubs were in an uproar about Grant’s inclusion, as illustrated by the York Age, “The kicking has commenced in the Atlantic Association. Washington and Baltimore refuse to play with Harrisburg unless Grant is left out, and Harrisburg says they must play with him or not at all.” Nevertheless, Harrisburg joined the league on July 21, accepting and continuing with Jersey City’s rather poor win-loss record.

The Baltimore Sun reported on July 25, “Many of the Baltimore players are strongly opposed to taking part in games with Grant, the colored third baseman of the Harrisburg club. The most decided objections are naturally made by [Pop] Tate and [Mike] O’Rourke, who live in Richmond, and [Reddy] Mack, who is a son of Kentucky. The men say that as Grant is the only colored player in the Association it is hardly fair to persist in keeping him as a regular member of the Harrisburg team in the face of the prejudice which is sure to be shown against him.”

Eventually, the sentiment waned; Grant played in Baltimore on August 15, an 8-3 win by the home team. According to the Washington Post, “Two thousand people saw the game today between the Baltimores and Harrisburgs. The game was marked by the sharp fielding of both sides, especially that of Grant, which was really commendable.” The Baltimore Sun complimentary noted, “Grant, the colored player, attracted to the grounds a considerable number of colored onlookers. He is of medium height, heavy set, but active as a cat, and his quick stops, followed by lightning throws, were cheered frequently. He is a great player, however, and strengthens the Harrisburg team greatly.”

He was not, however, welcomed off the field, reported the Baltimore Sun: “Grant, the colored shortstop, only associates with his fellow players on the field. The headquarters of the Harrisburg team in Baltimore are at Kelly’s Hotel, but Grant lodges and takes his meals at the house of Roy, the headwaiter of the hotel.” He ran into similar trouble in Wilmington, Delaware. The club had previously stayed at the Clayton House, but fellow guests complained about Grant’s presence and he was no longer welcomed. According to the Sporting Life, “Another hotel was sought, where the players were given rooms with the understanding that Grant must eat with the colored help or get his meals elsewhere. He accepted the latter alternative.” In Harrisburg he lived in a segregated rooming house.

On August 18, Grant’s glove played a key role in a 1-0 win over Newark, per the Washington Post, “Grant’s great stop and throw in the seventh inning won the game for Harrisburg.” The Sporting Life expounded (though they differed on the inning): “Grant’s phenomenal stop in the ninth inning, preventing the Newarks from [tying] the score, if not winning the game.” Harrisburg finished with a 58-72 record including Jersey City’s contests. Grant hit a solid .332 in 47 games. He was reserved by the club and spent the winter in Harrisburg.

Grant rejoined the Cuban Giants in early 1891. In May, they soundly beat the Gorhams twice, 18-10 and 17-2. The Gorhams, named after a Manhattan tavern, were formed in 1886 and quickly became one of the top black clubs of the day, rivaling the Cuban Giants for supremacy. Ambrose Davis, owner of the Gorhams, didn’t take the humiliation lightly. He raided the Giants for George Stovey and Clarence Williams. Sol White and Grant soon followed. Naturally, the Cuban Giants were severely wounded. As the Ansonia Sentinel put it, “The Cuban Giants, or what remains of the original club, have gone to pieces and the Gorhams have absorbed the largest portion of the nine.”

Davis then renamed his club the Big Gorhams. In his landmark work on black baseball history, Sol White identified the 1891 Big Gorhams as the best club of the nineteenth century. Manager Cos Govern, the original manager of the Cuban Giants, oversaw an infield that included George Williams at first, White on second, the strong-armed Grant at shortstop and Andy Jackson at third. Oscar Jackson played center field. The team’s catchers, Arthur Thomas and Clarence Williams, and pitchers George Stovey, Bill Selden and William Malone took turns in left and right fields. According to White, the team posted a record that year of 100+ victories against only 4 losses, but that seems a little exaggerated. At one point though, they won 41 straight.

The Big Gorhams briefly joined the Connecticut State League representing Ansonia. They posted an 8-10 record before the league disbanded. With those contests, Grant appeared in his final game in Organized Baseball. In 458 games in total, he batted .337 with an impressive .489 slugging average.

Regardless of their success on the field, the Big Gorhams were a financial failure. Grant joined the Cuban Giants for the 1892 season and was named captain. He remained with the team through 1897, usually serving as captain. Meanwhile, he spent winters in his hometown of Williamstown and played with area clubs, weather permitting, such as the Blackinton team in late 1896. Some sources list him briefly with the Page Fence Giants in 1897 or 1898, but that listing may be confused with Charlie Grant, another second baseman.

Grant played for the Cuban X-Giants in 1898 and ‘99, the top eastern club owned by Edward B. LaMar, a white Brooklynite. Created in 1896, the X-Giants in essence stole the Cuban Giants name and then pilfered their players and fan base. Grant and Sol White alternated between shortstop and second base. The team included familiar names such as Bill Selden, Andy Jackson and Clarence Williams. Grant joined the Genuine Cuban Giants in 1900, serving as captain, until being released in mid July. He rejoined the nine again in 1901. John Bright changed the name of the Cuban Giants in 1896 in response to Lamar’s X-Giants infringement. Bright now used the term “Original” or “Genuine” to refer to his nine.

In 1903, he played second base for the Philadelphia Giants, one of the strongest black clubs in the nation. At the end of the season, they faced the Cuban X-Giants in the first significant black playoff, losing 5 games to 2. At age 38, Grant’s career in professional ball ended. However, he may have played for semi-pro teams in New York City, as he still listed his occupation as “baseball player” in the 1910 U.S. Census.

Grant retired to Manhattan in anonymity in New York City, living in Greenwich Village. He married twice but had no children. Circa 1905, he married a New York native named Celia. The 1920 Census listed a wife named Melvinea, another New York native. He worked at various times as a waiter for a catering service, porter at a woolen house and as a “laborer.”

On May 27, 1937, Frank Grant passed away at age 71 at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan of arteriosclerosis. He received a pauper’s funeral and burial in an unmarked grave at East Ridgelawn Cemetery in Clifton, New Jersey. Black baseball heroes Sol White, Smokey Joe Williams, and Nux James served as pallbearers.

TOM BROWN ON FRANK GRANT

Longtime major league outfielder Tom Brown was quoted in the Washington Post on February 6, 1900, with the following praise for Grant (though Brown confused Grant’s first name as Hugh):

“One of the best second baseman the game has ever seen was the colored diamond athlete, Hughey Grant, who was at his best when he played on the Buffalo team. Grant’s great forte as a fielder was his sure-thing hands. He was as near perfection in gauging swift grounders as [Heinie] Reitz, than whom no finer hand-worker ever lived. Grant, however, had Reitz distinctly beaten as an all-around fielder, as he was faster on foot, covered larger area of ground, and was surer and quicker on double plays. He was a natural batsman, as many a twirler found to his sorrow.

Grant played no favorites at the bat. High curves, low out-shoots, or slow teasers served at a shot-putting gait all looked the same to Grant. The pitchers seemed to take a [fiendish] delight in deliberately firing the ball at his head with the intention of driving him from the plate, but they never succeeded in taking his nerve. In the annals of the game and in the achievements of such second basemen as [Jack] Burdock, Ross Barnes, Fred Pfeffer, and Yankee Robinson the name of Hugh Grant has been overlooked, though if he were a white man he would stand abreast of the others in the red-letter chapters of baseball.”

BUFFALO CORRESPONDENT TO THE SPORTING LIFE

The following is the complete (minus extraneous biographical material at the beginning and end), often-cited quote by the Buffalo correspondent to the Sporting Life (March 14, 1888) that declares Grant as the best ballplayer in Buffalo history:

“He is a great all-around player; he can fill credibly every position on the diamond, but his specialty is second base. Some consider him rather weak in touching base-runners, but I think he is fully as quick in that respect as any other guardian of ‘the key of the diamond.’ He is a very accurate thrower, and withal swift. He is exceedingly hard to fool at the bat, as his average of .366 will testify, and his shots are generally long. He led the league in the matter of extra [base] hits last season, having 27 two-base hits, 10 three-base hits and 11 home runs. He also led the Buffalo club in base-stealing. With all due credit to the ability of Hardie Richardson and Jim O’Rourke, I think I can say that Grant is the best all-around player Buffalo ever had.”

NED WILLIAMSON ON FEET-FIRST SLIDING

In the October 27, 1891 edition of the Sporting Life Ned Williamson, whose career spanned from the late 1870s to the 1890s, was quoted pertaining to the feet-first slide, under the heading, “The ‘Feet-first’ Slide Due to a Desire to Cripple Colored Players”:

“No,” said Ed Williamson, the once great shortstop the other day to a Chicago reporter, “ballplayers do not burn with a desire to have colored men on the team. It is, in fact, the deep seated objection that most of them have for an Afro-American professional player that gave rise to the ‘feet first’ slide. You may have noticed in a close play that the base-runner will launch himself into the air and take chances on landing on the bag. Some go head first, others with the feet in advance. Those who adopt the latter method are principally old-timers and served in the dark days prior to 1880. They learned the trick in the east.

The Buffalos – I think it was the Buffalo team – had a Negro for second base. He was a few lines darker than a raven, but was one of the best players in the old Eastern League. The haughty Caucasians of the association were willing to permit darkies to carry water to them or guard the bat bag, but it made them sore to have the name of one in the batting list.

They made a cabal against this man and incidentally introduced a new feature into the game. The players of the opposing teams made it their special business in life to ‘spike’ this brunette Buffalo. They would tarry at second when they might have easily made third, just to toy with the sensitive shins of the second baseman. The poor man played in two games out of five perhaps; the rest of the time he was on crutches. To give the frequent spiking of the darkey an appearance of accident the ‘feet-first’ slide was practiced.

The Negro got wooden armor for his legs and went into the field with the appearance of a man wearing nail kegs for stockings. The enthusiasm of opposition players would not let them take a bluff. They filed their spikes and the first man at second generally split the wooden half cylinders. The colored man seldom lasted beyond the fifth inning, as the base-runners became more expert. The practice survived long after the second baseman made his last trip to the hospital. And that’s how [King] Kelly learned to slide,” concluded the reminiscent Ned.

Some of Williamson’s facts may be off, but the sentiment and intention of the players is represented well. Also, he could have just as well been speaking of Bud Fowler as Frank Grant.

Notes

One source, Shades of Glory, page 60, states that Grant played ball for one of Frank Thompson’s teams in 1885. (Thompson was organizer of the Cuban Giants.) Supposedly, the nine was based at Hotel Champlain near Plattsburgh, New York, in the Adirondacks. However, the Hotel Champlain did not open until 1890 and wasn’t proposed to the community until August 1888, according to Clintoncountyhistorical.org. Plattsburgh only had two teams of consequence in 1885, Nameless and Williams.

James A. Riley in The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues lists Grant as a member of a club called the “Colored Capital All-Americans,” a team based out of Lansing, Michigan, in 1891. Grant didn’t otherwise play for a western team. In fact, Riley lists several eastern players with that club. Grant did play for the “Colored All-Americans” in 1889, a team composed of men from both the Cuban Giants and Gorhams that played mostly, if not entirely, in New York State. If the team I located – Colored All-Americans – actually contained the word “Capital” in its name, which is entirely possible, than the reference is to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Grant may have married more than twice.

Sources

Sarah Harding of the Williamstown House of Local History was most helpful in answering several questions about the area – particularly Grant’s probable high school – and providing a couple of items from its archives.

Aaron, Lawrence, “Paying Tribute to Forgotten Black Ballplayers,” Newjersey.com, August 2, 2006

Ancestry.com

Ansonia Sentinel, Connecticut, 1890

Baltimore Sun, 1890

Baseball-reference.com

Boston Globe, 1892, 1896

Brooklyn Eagle, 1887, 1890

Brunson, James Edward. The Early Image of Black Baseball: Race and Representation in the Popular Press, 1871-1890. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2009.

Buffalo Express, 1886-1887

Burgos Jr., Adrian. Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Bush, Susan, “Williamstown Honors Baseball Hall of Fame Inductee Frank Grant, Iberkshires.com, August 10, 2006

Chicago Tribune, 1899

Clark, Dick and Larry Lester. The Negro Leagues Book. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994.

Cleveland Gazette, 1889

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago, 1890

Elizabethtown Post, New York, 1885

Harrisburg Morning Patriot, Pennsylvania, 1890

Harrisburg Telegram, Pennsylvania, 1889

Hartford Courant, 1886

Hogan, Lawrence D. Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2006.

Holway, John. The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History. Fern Park, FL: Hastings House Publishers, 2001.

Johnson, Lloyd. The Minor League Register. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1994.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

Kirwin, Bill. Out of the Shadows: African American Baseball from the Cuban Giants to Jackie Robinson. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Kleinkhecht, Merl F., “Blacks in 19th Century Organized Baseball,” Baseball Research Journal, Cleveland: SABR, 1977.

Lebanon Daily News, Pennsylvania, 1890-1891

Lima Times Democrat, Ohio, 1894

Lomax, Michael E. Black Baseball Entrepreneurs, 1860-1901: Operating by Any Means Necessary. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003.

Louisville Post, 1888

Malloy, Jerry, “Out at Home,” The National Pastime #2, Cleveland: SABR, 1983, pp. 14-29.

Malloy, Jerry, “The Cubans’ Last Stand,” The National Pastime #11, Cleveland: SABR, 1992.

_____. Sol White’s History of Colored Base Ball With Other Documents on the Early Black Game 1886-1936. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

McKenna, Brian, “Bud Fowler,” SABR Biography Project

_____, “George Stovey,” SABR Biography Project

Middletown Daily Argus, New York, 1894

Middletown Daily Press, New York, 1892

Middletown Daily Times, 1893

Milwaukee Sentinel, 1888, 1897-1898

Mjagkij, Nina. Organizing Black America: An Encyclopedia of African American Associations. London: Taylor & Francis, 2001.

The Morning Record, Traverse City, Michigan, 1897

Newark Daily Journal, New Jersey, 1887

Newport Daily News, Rhode Island, 1895-1897

Newport Mercury, Rhode Island, 1896

New York Age, 1887-1890

New York Times, 1887-1892, 1901

New York World, 1891-1893

Nlbpa.com

North Adams Transcript, Massachusetts, 1896-1900

The North American, Philadelphia, 1899

Overfield, Joseph M., “When Baseball came to Richmond Avenue,” Niagara Frontier, published by the Buffalo Historical Society, Summer 1955

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams Before Black Men Played in the Major Leagues. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1970.

Pittsburgh Courier, 1937

Plattsburgh Sentinel, New York, 1885

Porter, David L. Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Ribowsky, Mark. A Complete History of the Negro Leagues 1884-1955. New York: Citadel Press Books, 2002.

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York: Carroll and Graf Publishers, 1994.

Rochester Union, 1887

Sporting Life, 1886-1898

The Sporting News, 1889

St. Louis Globe Democrat, 1886-1887

Syracuse Evening Herald, 1887

Syracuse Herald, 1889

Syracuse Standard, 1886-1887

Syracuse Sunday Herald, 1888

Thorn, John, “Wake of Echoes,” Kingston Times, March 9, 2006

Tiemann, Robert L. and Mark Rucker, eds. Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Toronto Daily Mail, 1887

Trenton Evening Times, New Jersey, 1898

Trenton Times, New Jersey, 1889

Washington Post, 1889-1890, 1900

Wikipedia.org

Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin, Pennsylvania, 1895, 1903

Yenowine’s News, Milwaukee, 1889

York Age, Pennsylvania, 1890

Full Name

Ulysses Franklin Grant

Born

August 1, 1865 at Pittsfield, MA (US)

Died

May 27, 1937 at New York, NY (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.