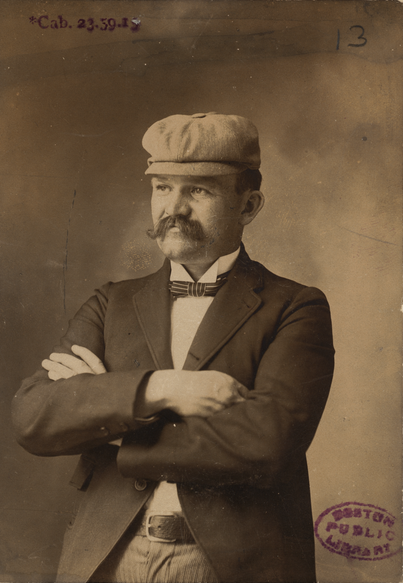

Nuf Ced McGreevy

If you take a close look at some of the iconic Boston baseball photographs created at the turn of the 20th century by Elmer Chickering, you might see him. He’s the mustached chap in the bowler cap holding his Brownie camera with Hi-Hi Dixwell at the groundbreaking for the Huntington Avenue Grounds; he’s the guy in his skivvies being pulled out of icy winter waters after swimming polar-bear style at the L Street Baths; he’s the head peeking over a Pittsburgh Pirate’s shoulder in a first-base-line team portrait taken during the first World Series; and he’s the Royal Rooter posing with a platoon of the Red Sox faithful holding a fistful of dollar bills and a megaphone in front of Boston’s South Station upon his arrival from Pittsburgh after singing “Tessie” at Game Seven of the 1903 World Series. “Nuf-Ced” McGreevy was his name. Base ball was his game.

If you take a close look at some of the iconic Boston baseball photographs created at the turn of the 20th century by Elmer Chickering, you might see him. He’s the mustached chap in the bowler cap holding his Brownie camera with Hi-Hi Dixwell at the groundbreaking for the Huntington Avenue Grounds; he’s the guy in his skivvies being pulled out of icy winter waters after swimming polar-bear style at the L Street Baths; he’s the head peeking over a Pittsburgh Pirate’s shoulder in a first-base-line team portrait taken during the first World Series; and he’s the Royal Rooter posing with a platoon of the Red Sox faithful holding a fistful of dollar bills and a megaphone in front of Boston’s South Station upon his arrival from Pittsburgh after singing “Tessie” at Game Seven of the 1903 World Series. “Nuf-Ced” McGreevy was his name. Base ball was his game.

Michael T. McGreevy was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, on June 16, 1865. He was the first child of Margaret (Glinnon) McGreevy and Michael McGreevy, Irish immigrants living at 11 Vernon Street in Roxbury, then an independent city neighboring Boston. In 1869 his parents gave young Michael a baby brother. His father, Michael McGreevy, worked as a day laborer in the building trade until his death on January 6, 1872, a victim of tuberculosis. Margaret and her two sons moved in with relatives at 7 Smith Street in the same neighborhood.1

Without a father, the young and competitive McGreevy grew up on the streets of Roxbury, played sandlot baseball and developed skills as an expert handball player. From an early age he was a dyed-in-the-wool baseball crank idolizing the Irish ballplayers who played for the hometown Boston baseball clubs at the old Walpole Street, Congress Street, and South End Grounds. His first idols on the diamond were characters like King Kelly, Old Hoss Radbourn, John Morrill, and Billy Nash, and by the time those players had reached their prime, McGreevy had moved out of the family home and taken a room at 29 Station Street in 1887, employed as a clerk at 1153 Tremont St.2

On October 8, 1890, McGreevy married Annie L. Downes. The couple moved into a house at 122 Vernon Street and started their own family when daughter Alice arrived about 11 months later. It’s not clear how he got into the spirits trade, but after being listed in city directories for several years as a clerk, McGreevy found his calling and opened his first saloon, on the corner of Cabot and Linden Park Streets in his Roxbury neighborhood. In the only surviving photograph of the exterior of that first saloon, McGreevy is seen leaning against the doorway entrance near a large hand-painted sign sponsored by a local brewer that read: “M.T. McGreevy & Co. Ales Wines and Liquors – A.J Houghton Co.’s Celebrated Lager.”

As a gregarious and popular barkeep, McGreevy quickly carved a niche for himself as a leader and organizer of many of his patrons who were fellow members of the Boston Elks Lodge and who shared his love for sport, particularly baseball. Boston, along with New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, had significant contingents of dedicated fans with close ties to the game’s early days, including Boston’s Arthur “Hi-Hi” Dixwell and New York’s Frank “Well-Well” Wood, who both gained notoriety as the sport’s most devout and vocal fans. In the 1880s New York City establishments like Nick Engel’s Home Plate steakhouse and saloon incorporated baseball themes and decorations and embraced ballplayers and the characters associated with the game. A rabid fan of the New York Giants, Engel organized a group of fans known as the High and Mighty Order of Baseball Cranks of Gotham, and also led a contingent of 160 New York fans by train to Baltimore for Opening Day in 1894.

When McGreevy opened his saloon the same year, he was following in the footsteps of Engel who was already exhibiting assorted cabinet photographs of players on the walls of the “Home Plate” and incorporating personal souvenirs from players like a telegram he’d once received from King Kelly, who also owned a New York City saloon with ex-umpire Honest John Kelly called the Two Kell’s. Famous for his tenderloin dinners, Engel regularly entertained the greats of the game including John Ward and Buck Ewing and when he died in 1897 at the age of 52, the members of Boston Elks Lodge No. 10, likely including McGreevy, traveled to his funeral service in New York City to pay their respects to one of the game’s greatest fans.

Perhaps influenced by Engel’s Home Plate, McGreevy took the concept of a baseball-themed saloon to a new level and gradually transformed his establishment into a gallery of baseball photographs and lithographs that immortalized his customers’ favorite players. Operating in a politically charged era when Irish politicians, including Mayor Pat Collins and Congressman John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, were consolidating their ethnic base in Roxbury and the neighborhoods beyond, McGreevy emerged as an organizer and leader in a community that was consumed by baseball. McGreevy and his customers mimicked the pubs from the old country that served both as watering holes and clubhouses for soccer teams and other athletic organizations. In Roxbury McGreevy and his fellow cranks were devoted to the hometown Beaneater baseball clubs managed by Frank Selee that featured native New England stars like Hugh Duffy, Fred Tenney, Marty Bergen, and a third baseman from Buffalo named Jimmy Collins.

The affinity McGreevy and his followers had for the Boston club culminated in a frenzy of fanatic devotion in September of 1897, when McGreevy organized an army of Boston fans to travel via rail to Baltimore and root for the Beaneaters in what would be the deciding games for the National League pennant. Wearing badges incorporating beanpot themes created by the Boston Globe and Boston Herald identifying themselves as the “Boston Rooters,” the group of nearly 200 fans toured the streets of Baltimore with a hired marching band. Led by Congressman Fitzgerald, the group ended at the Baltimore grounds behind the Boston dugout where McGreevy and the entire Boston contingent rooted on their boys “with horns, rattles and a specially arranged battle-cry.”3 Sporting Life also reported that after the Rooters posed for a photograph with the Boston team on the steps of Baltimore’s Eutaw Hotel, a superstitious Sliding Billy Hamilton blamed a loss in that series on posing with the Rooters. However, before the road trip was over Boston clinched the pennant and McGreevy and his Roxbury Rooters had returned home victorious, “enthusiastic beyond measure with their reception and treatment, and (would) never forget the trip.”4 As one cohesive cheering unit, McGreevy and his cohorts had successfully transformed themselves into baseball’s original “tenth man.”

The trip of 1897 laid the groundwork for McGreevy’s more formalized contingent that would later become known famously as the Royal Rooters, a group dedicated to traveling and rooting for Ban Johnson’s newly organized American League club in Boston that snatched Jimmy Collins and other stars away from the longstanding fan favorite Beaneaters. As noted by Boston Globe scribe Tim Murnane, a Royal Rooter sat atop the world of fandom, distinguishing himself as a cut above the lower classes of baseball fans for his willingness to travel on his own dime to root for his club in enemy territory. McGreevy and his men revolutionized the concept.

The trip of 1897 laid the groundwork for McGreevy’s more formalized contingent that would later become known famously as the Royal Rooters, a group dedicated to traveling and rooting for Ban Johnson’s newly organized American League club in Boston that snatched Jimmy Collins and other stars away from the longstanding fan favorite Beaneaters. As noted by Boston Globe scribe Tim Murnane, a Royal Rooter sat atop the world of fandom, distinguishing himself as a cut above the lower classes of baseball fans for his willingness to travel on his own dime to root for his club in enemy territory. McGreevy and his men revolutionized the concept.

By 1900 McGreevy had moved his Linden Park saloon to a larger space in a standalone structure at 940 Columbus Avenue in Roxbury, located equidistant from the South End Grounds and the site of the Huntington Avenue Grounds, which was built the following year. In 1901 McGreevy, Tim Murnane, and 19th-century fan extraordinaire Hi-Hi Dixwell appeared with a large contingent of Boston Rooters to break ground for the new ballpark on Huntington. McGreevy placed a photograph of the groundbreaking ceremony in a display window at his new location, the first of many in his collection that would embrace the new American League franchise that swayed Roxbury loyalties from the National League. By the time the new American League club played its first game in Boston, in 1901, McGreevy’s bar was known as the 3rd Base Saloon, nicknamed as such because it was said to be any fan’s “last stop before home.”5 However, the name appears to have also been in part a tribute to local hero and third baseman Jimmy Collins, upon whose shoulders the success of the fledgling American League franchise rested. With Collins already in the American League camp, it only took cheaper ticket prices to secure the full devotion of McGreevy’s Rooters for Boston’s entry in Ban Johnson’s competing big league.

By 1901 McGreevy was already being identified by the nickname Nuf-Ced, a term he was said to have coined after he pounded his fist down on his oak bar. One of his bartenders, Tom Kenny, experienced Nuf-Ced in action and said his boss:

“got his tag from a short terse statement he’d make whenever a customer from the Midwest might become a little over-enthusiastic over Bill Bradley’s third-basing talents, as compared to Jimmy Collins, the idol of the Boston fans. … When the argument started to heat up, Mr. McGreevy would say ‘Nuf Ced,’ which meant the agifiers would have to pipe down or be ejected. And he always had a big strong bouncer on the payroll to see that the peace prevailed.”6

As the Boston Americans drew crowds to the new Huntington Avenue ballpark, McGreevy’s saloon kept its own bouncers busy and became a drawing card itself, before, during, and after games. Taking advantage of the business opportunity, McGreevy enhanced his own developing celebrity in town by placing ads on the covers of the Boston scorecards and programs that read: “McGreevy on the Avenue … Nuf Ced.” In the coming seasons he would even buy ad space on the ballpark’s left-field wall so fans could read: “What’s the last stop before home? Third Base – Nuf Ced.”

McGreevy’s saloon became the headquarters for the baseball community during the season and extended well into the Hot Stove League during the winter. Season after season, the establishment gradually was transformed into what would become baseball’s first true museum, with nearly every square inch of wall space dedicated to small and large mounted pictures of former Boston teams and massive individual portraits of stars dating back to King Kelly and the heroes of McGreevy’s youth. Game-used equipment, including gloves and balls, was hung behind the bar and McGreevy went so far as to fashion the game-used war clubs of star players like Cy Young, Nap Lajoie, and Freddie Parent into lighting fixtures that hung from the high ceilings of the saloon. At the end of the bat barrels were affixed frosted glass domes transformed into baseballs with hand painted laces.7 Players and fans commiserated and drank among McGreevy’s collected relics of the game with characters who were also notorious odds-makers and gamblers like Joseph “Sport” Sullivan, who would later be implicated in the scheme to fix the 1919 World Series. It was likely at McGreevy’s that Sullivan first became friendly with Eddie Cicotte a decade before the scheme was hatched at the nearby Buckminster Hotel. At McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon, baseball and betting went hand-in-hand and McGreevy was the arbiter of all baseball arguments and skirmishes. With so many visiting baseball writers, players, and executives frequenting his establishment, Nuf-Ced began to cultivate a national reputation as baseball’s most devoted fan, one who also had the inside dope on the diamond at his disposal.

Without question it was at the World Series in 1903 that McGreevy and his Royal Rooters solidified and expanded upon their legend as living good-luck charms who could invariably root their beloved Boston teams to victory. Traveling back and forth between Pittsburgh and Boston, McGreevy and his henchmen Charlie Lavis and Louis Watson adopted the popular song “Tessie” as the Boston fight cry and taunted the opposition with slurs and chants to distract them from the task at hand. In Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times, Pirates third baseman Tommy Leach recalled McGreevy’s antics in Games Four and Five and how he and the Rooters sang, “Honus, you hit so badly” in place of “Tessie, you make me feel so badly” from their reserved seats in Section J whenever the great Wagner came to the plate. Leach’s first-hand account is perhaps the greatest testament to McGreevy’s legacy as the ultimate fan as he recalled:

“I think those Boston fans actually won that series for the Red Sox. We beat them three out of the first four games, and then they started singing that damn ‘Tessie’ song, the Red Sox fans did. They called themselves the Royal Rooters and their leader was some Boston character named Mike McGreevey. He was known as “Nuf-Sed” McGreevey, because any time there was an argument about anything to do with baseball he was the ultimate authority. Once McGreevey gave his opinion that ended the argument: nuf sed!”8

When McGreevy returned to Boston on the same train as Cy Young and the team after the “Tessie”-fueled victory, he was unaware that some fellow Rooters had dressed up the exterior of his saloon with patriotic bunting and a painted sign hailing the Boston club as soon-to-be World champs. The Boston Globe reported how upon his return McGreevy, “one of the prime movers of the Pittsburg trip,” would be surprised to see 3rd Base decked-out in his honor.9 Atop the entrance of the 3rd Base Saloon the life-size mannequin known as McGreevy’s “Baseball Man” was dressed in a flannel Boston uniform doing his best impersonation of King Kelly and looking down upon the horse-drawn buggies and carriages that made their way down Columbus Avenue towards the ballpark. Riding the momentum of the notoriety he received during that first World Series, McGreevy was further embraced by the baseball press and transformed into a local celebrity with his exploits (just like those of the players) rendered in cartoons drawn by Wallace Goldsmith and Sid Green for the Boston daily newspapers.

When McGreevy returned to Boston on the same train as Cy Young and the team after the “Tessie”-fueled victory, he was unaware that some fellow Rooters had dressed up the exterior of his saloon with patriotic bunting and a painted sign hailing the Boston club as soon-to-be World champs. The Boston Globe reported how upon his return McGreevy, “one of the prime movers of the Pittsburg trip,” would be surprised to see 3rd Base decked-out in his honor.9 Atop the entrance of the 3rd Base Saloon the life-size mannequin known as McGreevy’s “Baseball Man” was dressed in a flannel Boston uniform doing his best impersonation of King Kelly and looking down upon the horse-drawn buggies and carriages that made their way down Columbus Avenue towards the ballpark. Riding the momentum of the notoriety he received during that first World Series, McGreevy was further embraced by the baseball press and transformed into a local celebrity with his exploits (just like those of the players) rendered in cartoons drawn by Wallace Goldsmith and Sid Green for the Boston daily newspapers.

When the Giants refused to play Boston after the 1904 season, McGreevy and the Rooters settled on an American League pennant and channeled some hero-worship towards the team manager, Jimmy Collins. The third baseman was honored by McGreevy and Charlie Lavis with a massive silver loving cup paid for by contributions made by the rooters and Boston fans to the Boston Journal newspaper. McGreevy sent in his own $6 contribution towards the cup he hoped would bring good luck and the pennant to Boston. In a note to the Journal he referred to the honor they were bestowing upon Captain Collins as a “Crack-a-Jack.”10

Collins and his men faced Jack Chesbro and the New York Highlanders at season’s end in a dead heat. McGreevy and Louis Watson paraded on top of the visitors’ dugout at Hilltop Park in Upper Manhattan with megaphones leading organized chants and renditions of “Tessie” that were said to have rattled the New York nine. Chesbro, who won 41 games that season, threw a wild pitch to blow the pennant in the ninth inning and McGreevy and his boys went wild. They marched victoriously down 165th Street with a 20-foot banner identifying the posse as the “Boston Rooters” and they posed for a group portrait that was destined for the walls of the 3rd Base Saloon picturing McGreevy and the Rooters savoring their victory over New York. By the time the 1904 season had ended, McGreevy had revolutionized the culture of the fan as the first rooter documented in a photograph who displayed his own signs at the ballpark. At Hilltop Park McGreevy had held a sign that read, “Boston Wants These Games – Nuf-Ced” and another directed at the New York Giants owner who declined to play in a World Series, which read: “Mr. Brush We’re on Plush, where are you? Don’t be Vain, Give us a Game. One or Two. Do. Do. My Huckleberry Do!”11

As much as Michael T. McGreevy was devoted to the Boston baseball teams, he was just as much in love with the game itself. When his beloved team failed to make it into the postseason in 1906, he still traveled to Chicago for the first intracity World Series, between the White Sox and the Cubs, and was recognized in the national baseball press for his acquisitions of several large photographs of the 1906 Series.”12 In January 1906, the New Year’s resolutions of baseball notables were published in the sporting papers, including Cy Young’s desire to “pitch a few more no-hitters” and Ban Johnson’s vow to call Charles Comiskey a “good fellow.” After the Series of 1906, Nuf-Ced made good on his published resolution: “To get a few more souvenirs for his champion collection.”13 It was in 1907, however, that Nuf-Ced made his greatest acquisition to date after learning that a gold medal presented to King Kelly as the Champion Base Runner of the Boston team in 1887 had been deposited in a New York City pawnshop window looking “tarnished, dusty and forgotten.”14 Knowing how much he wanted it, his fellow Rooters purchased the medal for $200 and presented it to McGreevy at the 3rd Base Saloon, where the 33rd-degree rooter polished it and placed it in a display case for all fans to see.

By 1906 McGreevy’s baseball museum was a well-known destination for fans and players alike, a spectacle for any baseball enthusiast of that era. As historian John Thorn has said, “McGreevy’s saloon looked like Cheers after a Victorian interior decorator had got a hold of it.”15 The saloon resembled the salons of Europe where Rembrandts and Vermeers were assembled to cover entire walls, except that McGreevy’s masterpieces were the works of Hy Sandham, Prang, Hastings, Horner, and Chickering. The importance of having your picture up on the walls of McGreevy’s baseball shrine was described by Nuf-Ced himself in a broken-English poem he published on the cover of the Boston Americans scorecard sold at the ballpark in 1906:

“Kum, Kum, pla bal & get your piktur up at 3rd Base. The bst koleksion in the Kuntry,

A histry uv the game in pikturs, The tok uv the base bal world.

Have u seen them?

& 2 qot Kaptain Fred Clark (Pitts)

“Kum, Kum b alyv, b alyv, Get in the game.” Nuf Ced M.T. McGreevy 940 Columbus Av.

While McGreevy was a rabid collector, he was also a ballplayer at heart, and known as a skilled amateur from accounts of the day that reported both his play and financial support for his own semiprofessional teams. He ate, drank, and slept baseball and extended his devotion to the local sandlots in Roxbury, sponsoring some of the earliest youth and junior baseball clubs dressed in uniforms with “Nuf-Ced’s” emblazoned on their chest. It was reported that McGreevy had “organized the youngest uniformed team in Massachusetts” and that the youth team readily challenged “any nine or ten year old players in the state.”16

McGreevy and his clan also liked to play against the old pros and after each season would gather at O’Brien’s Sunset Farm in rural Holliston, Massachusetts, to play a pickup game followed by a lively smoker that usually honored one of the greats of the game. In McGreevy’s presence were old-time greats like the Heavenly Twins Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy, Rooters Jack Dooley and Charlie Lavis, sportswriters including Paul Shannon and Tim Murnane, and current stars of the game like Hughie Jennings, who was honored with his own Winter League event in 1913.17

But baseball didn’t end in Holliston for McGreevy and the Rooters, who also saw fit to make annual trips at their own expense to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to follow the club. Each season the Boston contingent including McGreevy and fellow Rooters like Mike Regan, “Uncle Bill” Cahill and C. F. Madden, “The Roxbury Kid,” would flee the frigid temperatures of Boston and travel by rail with the players to spring training, where they were treated like celebrities. Upon his arrival at the Eastman Hotel in 1908, McGreevy was described in a Hot Springs newspaper as “a fan known all over the country.”18

According to the Boston Post, as early as the spring of 1905, McGreevy was proving himself as a “bit of a player” against the big leaguers. The Post quoted Cy Young as saying that he could get McGreevy signed by a team in the South if he ever agreed to cut off his mustache.19 McGreevy regularly suited up in his own Boston uniform and played so well in exhibition games in 1908 that the manager of the Natchez club of the Cotton States League saw him playing in Hot Springs and actually inquired if he was available for purchase. Playing the manager for a fool, Red Sox owner John I. Taylor fielded a first offer of $200 and promptly upped the price to $300, which was accepted. Upon learning that he was sold, McGreevy said to the Natchez manager, “I guess you’ve been handed a good sized lemon.” Realizing he’d been had, the Natchez man first drew for his gun, but realizing the prank was good-natured and the joke was on him, calmed down when the Boston men bought a few rounds for his men.20 Thus grew the legend of McGreevy, who was described in the Arkansas Gazette as a “wonder” discovered by President Taylor and “in all probability a member of the Boston team for the upcoming season.”21 It was also reported that Hugh Duffy had attempted to buy him for the Providence club and Barney Dreyfuss for the Pittsburgh Pirates. One spring Nuf-Ced even jokingly signed an official contract with the Boston club.

McGreevy was also famous for showering the real players with gifts and awards and at spring training in 1908 he offered a diamond ring to the Boston player who could steal the most bases during the coming season. It was said that his offer would “increase the number of those who try to steal ‘Third Base’ on the way home.”22 Making good on his word at Hot Springs in 1909, McGreevy proffered a “nice speech” and presented winner Amby McConnell with an impressive $250 diamond ring.

For McGreevy and the Rooters who accompanied him, the spring ritual was all fun and games, as evidenced at a “cakewalk” given by the “colored waiters” in the Arlington Hotel’s skating rink. The local press reported that McGreevy and New York Giant mascot Charles “Victory” Faust had agreed to referee the event and that they even sought out hotel guest and multimillionaire Andrew Carnegie to join them.23 In his day McGreevy rubbed elbows with the rich, the notorious, and the poor with relative ease and by 1911 he was accompanying the Red Sox owners on the “Red Sox Special” train headed to spring training in California, where the Los Angeles Express described him as the “Oldest Baseball Rooter” and the game’s greatest fan, coast to coast.24

Aside from baseball, Michael T. McGreevy was also known locally in Boston as “one of the best all-around athletes of his age” and was similarly accomplished as a champion handball player known to enter local and regional competitions as well as promoting matches that were wagered upon heavily.25 He once arranged a $100 match at the L Street Baths between New Yorker Parkie Donegan and Boston’s Dick Fitzpatrick in which “considerable money changed hands on the result.”26 Similar challenges were presided over by McGreevy at the candlepin bowling alley in the basement of his 3rd Base Saloon. In 1910 McGreevy was famously challenged to a bowling match by Boston Doves manager Fred Lake and succumbed to Lake by ten pins at the neutral site of Joyce’s Lanes in Boston. Losing the challenge, McGreevy took Lake and his friends out to dinner to make good on the wager.27

But McGreevy garnered even more notoriety for his athletic activities in the dead of winter at the L Street Baths. It was on the frozen waters of Boston Harbor that McGreevy exhibited his ice-skating skills dressed in nothing but bathing trunks for a motion-picture camera in the winter of 1906. Afterwards, with the film reels in hand, McGreevy took the Boston Americans to a “local picture house” where his antics on skates made a “big hit with the players as well as with the rest of the audience.”28 In February of 1910, McGreevy was also profiled in a feature article in Baseball Magazine inspired by his other winter skill, “Swimming in Ice Water,” which was also captured on the 1906 motion picture. McGreevy and several of his rooter pals had for decades swum polar-bear style in the icy waters after playing some vigorous games of handball. When asked by Baseball why he and his fellow L Street Brownies ventured into the treacherously icy waters, McGreevy said that he and his pals enjoyed their swims so much during the summer and through October that “someone suggested that we stick it out all Winter.” McGreevy added, “The idea made a hit and it was carried by a unanimous vote. It was easy. We grew used to the gradual change in the weather and never minded it a bit.”29 Each winter, McGreevy appeared on the pages of virtually every Boston newspaper in underwear and his ice skates. He told the Boston Post, “I have gone out swimming every day this winter, and look at me. I never felt better in my life.” The Post added, “His eyes sparkled. He is patiently waiting for the baseball season to begin and is pining for another World’s Series next fall.”30

It was in the year of 1912, in the newly constructed Fenway Park, that Nuf-Ced McGreevy and his Royal Rooters reached the apex of their careers in baseball fandom. They rooted Jake Stahl’s Red Sox all the way to the American League pennant in the newly christened ballpark, and the rooting alliance between McGreevy and John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald reached new heights. McGreevy attended every World Series and in 1911 sat in a section reserved for official scorers and the press at the Polo Grounds in New York and at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. In 1912 the Royal Rooters returned to October form, led by McGreevy and Fitzgerald, who by then was the well-established and powerful mayor of Boston. Challenged by the Giants of John J. McGraw and Christy Mathewson, McGreevy and Fitzgerald organized the largest-ever contingent of Royal Rooters to travel to New York City; the mayor secured 300 tickets from the Giants, although there was an army of 1,000 Rooters who wanted to make the trip.

Upon their arrival in New York, the Rooters “caused quite a stir” as they paraded down Broadway in automobiles raucously taunting Gothamites with megaphones and noisemakers singing “Tessie” and a new number called “Knock Wood,” penned by McGreevy in tribute to Red Sox pitching ace Smoky Joe Wood.31 The words to the songs were printed on cards McGreevy produced for the trip depicting a cartoon of him and the “Roxbury Rooters” that read: “At Baltimore in ’97, Pittsburg in ’03, New York ’04, with the odds against us in the enemy’s battlefield we cheered them on to victory and brought home the flag. Now for New York 1912 –“NUF CED.”

McGreevy and Fitzgerald led the Rooters in organized songs and chants at the Polo Grounds and marched with the Boston Elks band around the perimeter of Fenway Park when the Series returned to Boston. But McGreevy and the Royal Rooters would experience some unexpected drama at Fenway for Game Seven after they realized Red Sox management had sold off their left-field reserved seats to other fans, causing a ruckus by Duffy’s Cliff as the Rooters had to be restrained by mounted police. Irate at Red Sox executive Robert McRoy for selling their seats, McGreevy and the Rooters announced that they would be boycotting Game Eight (Game Two ended in a tie), also at Fenway, despite the fact that Red Sox management found space for them in standing room among the other 32,000 fans at Fenway that day.32

McGreevy’s fellow Rooter, the bandleader Johnny Keenan, said, “We are through with the Red Sox, so far as the rooting goes, and we will not attend the final game tomorrow as a body.”33 Lots of fans followed suit and only 17,034 showed up at Fenway for the deciding game of the World Series. However, the Rooters’ stand may have had more to do with McGreevy and the boys having inside dope that the Series wasn’t on the level and, perhaps, may have known that the Red Sox would win the deciding game as rumors swirled that players were disgruntled with management. Notwithstanding, McGreevy and the Rooters jumped back on the bandwagon quickly as the Red Sox took Game Eight from the Giants and the world championship returned to Boston.

McGreevy and Fitzgerald joined automobiles transporting the players and led a victory parade from Kenmore Square to Faneuil Hall, where the champions were tendered a grand reception compliments of the mayor and the Royal Rooters. Honey Fitz called it the greatest reception he had ever witnessed in Faneuil Hall and McGreevy led his platoon of marching Rooters through the streets like a conductor at Symphony Hall. The outpouring of support McGreevy and the Rooters showered on the players cemented the feeling that they had no axe to grind with the players and with an apology in hand from Sox president and owner Jimmy McAleer, the local press reported that the entire ticket debacle would “probably be largely forgotten before the winter was over.”34

With Boston’s return to baseball prominence and another world championship under McGreevy’s belt, the Rooters continued their support of both the Red Sox and Boston Braves franchises. In 1914 McGreevy organized another road trip to the World Series in Philadelphia to support George Stallings’ Miracle Braves against Connie Mack’s Athletics. Nuf-Ced produced specially printed song cards and badges for the Royal Rooter, contingent, which included Mayor Fitzgerald, his newlywed daughter, Rose, and her husband, Joe Kennedy. Both newlyweds sported “Royal Rooter” badges made especially for the Series by McGreevy and Fitzgerald. However, Nuf-Ced would miss the Braves’ victory after receiving the tragic news of his brother’s death in Maine via telegram at the Series.

Under McGreevy’s continued leadership the fraternity of fans made road trips to Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Chicago and experienced additional World Series triumphs for the Red Sox in 1915, 1916, and 1918. In 1915, with Fenway Park less than strategically positioned near McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon on Columbus Avenue, the barkeep decided to move his business and baseball museum to a corner property at Tremont and Ruggles Streets. McGreevy’s saloon continued to flourish at its third location until the Volstead Act and Prohibition closed its doors in 1920, just six days before Babe Ruth was sold to the New York Yankees. While Prohibition was a death blow for McGreevy and the Rooters, it was the sale of Ruth that signified the nails in the coffin for golden age of the Royal Rooters. Upon learning of the Babe’s sale to Jacob Ruppert, Nuf-Ced told reporters prophetically, “Every real Boston fan will regret his departing.”35

As for Prohibition, McGreevy chalked it up as the result of “bad conditions brought about by intoxicating liquors” but he also predicted in a Boston Post “Prohibition Forum” that the old days would soon return in a modified form when the powers that be realized “the bad conditions under Prohibition.” Nuf-Ced was quoted as saying, “Light beer and wine will solve the problem,” and added this parting shot: “With cheap whiskey on the increase and no beer, surely there are trying times ahead.”36 With his beer taps dry and his back bar devoid of the Ky. Taylor’s Whiskey that had occupied the shelves for decades, McGreevy’s baseball museum stood frozen in time until 1923, when Nuf-Ced leased the space to the Boston Public Library to create an annex for the Roxbury neighborhood that had at once been home (along with Jamaica Plain) to at least 24 breweries.37 Upon its closing, the Boston Traveler published a nostalgic farewell to the former Boston landmark and what the writer called the “ghost of McGreevy’s cellar,” the stuffed and mummified “Baseball Man” dummy that used to sit atop the entrance of the once famous watering hole that was also known as “The Baseball Place.” The Traveler reported, “The room that once resounded with wholehearted laughter, where stories of Boston’s baseball victories were the all-absorbing theme of history and fiction, where the ringing strains of ‘Tessie,’ the old Boston baseball war song made the rafters tremble, that room is now strangely silent – almost deathlike.”38

McGreevy himself reminisced about his old bar and his baseball souvenir collection, which included not only a comprehensive lineup of pictures of the diamond stars but game-used bats, balls, and gloves used by legends like Kelly, Anson, Duffy, Speaker, and Ruth. McGreevy decided that the best fate for his collection was to donate it to the Print Department at the Boston Public Library so that future generations could experience Boston baseball’s glory days through his pictures. The library’s director, Charles Belden, recognized the significance of McGreevy’s collection and welcomed the donation that constituted what he viewed as an “accumulation of photographs showing the evolution of our great national game over a period of fifty years.”39

The vast collection included everything from an 1872 image of Harry Wright’s Boston club in front of a primitive wooden grandstand featuring a “Refreshments” sign to a 1904 shot of heavyweight champ John L. Sullivan in the Boston dugout with Jimmy Collins. The library staff at the main branch in Copley Square took roughly 200 rare photographs out of the original frames that once hung on the walls of the 3rd Base Saloon and stamped them with the identification mark, “M.T. McGreevey Collection.” Books replaced the bottles at the former bar location and the show window that used to exhibit daily baseball scores and statistics was reconfigured with suggestions of literature available at the annex for Roxbury residents. The Red Sox were replaced by Shakespeare with a transition from the “dispensation of lager” to the “distribution of letters.” No longer would Nuf-Ced’s old grandfather clock, which incorporated a bat for a pendulum and a ball for a weight, “impatiently count off the seconds from game to game.” It was the end of an era.40

After his collection was deposited at the library, Nuf-Ced and the Royal Rooters vanished further from the baseball scene with each passing season. In 1926 the Red Sox named old Rooter favorite Bill Carrigan as manager and McGreevy called for a short-lived resurrection of the original Royal Rooters. Nuf-Ced told reporters, “Carrigan’s return is just what the Boston fans have been waiting for.” Although the over-the-hill McGreevy thought that Carrigan was “a born fighter who command(ed) the respect of the players,” the return of the rooters never took flight and the Sox remained in the American League cellar.41

In 1930 McGreevy and some former fellow Rooters made it out to Braves Field to honor and support retired Red Sox catcher Lou Criger in an old timer’s game to benefit the disabled veteran. McGreevy couldn’t control his glee as he told the Boston Post, “What a kick, what a thrill. I felt 25 years younger when I saw the old-time stars coming to bat and showing their old-time stuff.” McGreevy got to commiserate once again with Red Sox legends Jimmy Collins, Candy LaChance, and Freddy Parent and contributed $25 to the cause for Criger. McGreevy made a point to tell the organizers of the event, “Distribute tickets among some poor kids or disabled veterans that they may enjoy the same thrills that I am going to get.”42

In 1939, to celebrate baseball’s mythical centennial, the Boston Public Library exhibited choice selections from the McGreevey Collection in a store-front window at Filene’s department store in downtown Boston, including one of the oval portraits of Nuf-Ced that once hung above the back bar in his Roxbury watering hole. In that store window the portraits of Fred Tenney, Hughie Duffy, and King Kelly joined large team portraits of almost every prominent Boston nine of the 19th and early 20th centuries. McGreevy was so far removed from the modern baseball scene that a writer from the Boston Transcript commented on the Filene’s display and referred to Nuf-Ced in the past tense.43 But McGreevy was still alive and kicking and after the Filene’s display returned to the library he was able to witness the naming of a Boston street after him, a portion of Longwood Avenue in Roxbury renamed McGreevy Way.44

At the age of 74, Michael McGreevy expressed his hope that the baseball trinkets and souvenirs he’d retained would make a nice exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, but aside from an article in the Globe in 1938 picturing him showing off his prized possession, the King Kelly gold medal, his plans never came to fruition.45

On February 2, 1943, Michael T. “Nuf-Ced” McGreevy, the acclaimed “King of the Rooters,” died at the age of 77, a victim of heart failure. A few weeks after his burial at Mount Calvary Cemetery in Roslindale, his 13-year-old granddaughter, Alice Ann Thompson, strolled into the offices of the Boston Globe and handed over his King Kelly medal to sportswriter Melville Webb. McGreevy’s last wish was that his most prized artifact be returned to the Globe and then donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Webb ran a story with a headline: “ ‘Nuf-Ced’ Wills Medal to Globe: Asks That Baseball Prize Be Sent to Hall of Fame.” Even in death, Nuf-Ced figured out a way to get his mug in the Boston papers.46 Even The Sporting News covered his passing and noted that the Royal Rooters originator “hit the front pages as far back as 1897.”47

After his death McGreevy’s legend was kept alive by fellow rooters like Jack Dooley, who recounted the stories of the old days for a new generation of fans, and by his old employees like Fenway Park attaché Tom Kenney, who recalled bartending at 3rd Base in the good old days when the likes of Jimmy Collins and Babe Ruth would drop by the bar “to do a little fanning with Nuf-Ced.”48 McGreevy gave Kenney a job shortly after he came to Boston from Galway, Ireland, and he never forgot the generosity of the man who always “had a nice free lunch at the end of the bar and a fellow to wait on the trade.” Kenney recalled, “You might say a lot of fellows got as far as third base, but sometimes it took them a long time to get home.”49

A testament to McGreevy’s legacy as baseball’s greatest fan was also offered up by his baseball fan wife, Annie, in 1955 at a time when Ted Williams wasn’t sure if he’d re-sign with the Red Sox. Blind and on her deathbed, the 87-year-old widow was receiving Holy Communion from a visiting priest when she said, “Tell me, Father, has Ted Williams signed up yet? I’m saying prayers that he does.” Considering her own condition, the priest was surprised she wasn’t saying prayers for herself as she was clearly in her last days. Boston American reporter Alan Frazer wrote, “Mrs. McGreevy had just time enough to get to Heaven” and “rejoined ‘Nuf-Ced,’ the most loyal fan the Red Sox ever had, when Ted announced he was coming back.” Frazer added, “Good night, Mrs. McGreevy, I know where you are.” Annie McGreevy passed away on May 8, 1955, a few days after a Boston American headline read: “Ted’s Return Answered Dying Woman’s Prayers.” Nuf-Ced.50

While Nuf-Ced McGreevy was mentioned every now and then in the Boston newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s, baseball’s greatest fan and Boston’s Royal Rooters faded away into relative obscurity. In 1970 historian Harold Seymour and his wife, Dorothy, utilized Nuf-Ced’s collection for Baseball: The Golden Age, but it wasn’t until 1979, when authors Daniel Okrent and Harris Lewine published The Ultimate Baseball Book, a coffee-table tome that featured numerous selections credited specifically to the Boston Public Library’s “M.T. McGreevey Baseball Picture Collection.” It was the first time in years that the general public got a peek at a large portion of the images that once graced the walls of the nation’s first and foremost sports bar, and it sparked the interest of other baseball authors who sought out rare and captivating baseball photography from the turn of the century.

In 1986 author Glenn Stout was employed at the Boston Public Library and essentially rediscovered Nuf-Ced and his remarkable collection in the library’s Print Department, along with McGreevy’s personal scrapbooks and papers. Stout was the first to research and write about the man and his career and reintroduced McGreevy to Boston fans in several articles, including one which was published in Sox Fan News in August 1986 under the title, “The Grand Exalted Ruler of Rooters Row.” With Stout’s promotion of the man and his collection, McGreevy’s photographic treasures became even more popular with authors including Sports Illustrated’s Frank Deford, who used the McGreevey Collection to write a 1988 article, “Huge Commotion in Mudville,” that included a profile of Nuf-Ced.51

In the early 1990s filmmaker Ken Burns worked with the McGreevey Collection and in 1994 Nuf-Ced was reintroduced to a national audience in the award-winning documentary film series Baseball, which featured a full segment under the title “Nuf-Ced” and utilized the library’s images of the 3rd Base Saloon, McGreevy, and the Rooters.

In 2000 Stout and co-author Richard Johnson began their definitive Red Sox history, Red Sox Century, with a scene from McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon and incorporated many of Nuf-Ced’s images throughout the book, as did the 2005 book Boston’s Royal Rooters and the 2007 documentary film Rooters: Birth of Red Sox Nation, both written by this writer. When Rooters aired on the cable channel NESN, Red Sox fans witnessed for the first time the original 1906 motion pictures of Nuf-Ced frolicking in the flesh with the rooters and “brownies” at the L Street Baths.

In 2004 Nuf-Ced was immortalized in song by the Boston punk rock band the Dropkick Murphys, who reworked the turn-of-the-century Red Sox fight song “Tessie” with the help of Boston Herald baseball writer Jeff Horrigan and backup vocals by Red Sox players Johnny Damon, Bronson Arroyo, and Lenny DiNardo. The Dropkicks evoked the spirit of McGreevy as they sang:

Tessie, Nuf Ced McGreevey shouted

We’re not here to mess around

Boston, you know we love you madly

Hear the crowd roar to your sound

Don’t blame us if we ever doubt you

You know we couldn’t live without you

Tessie, you are the only only onlyThe Rooters gave the other team a dreadful fright

Boston’s tenth man could not be wrong

Up from “Third Base” to Huntington

They’d sing another victory song 52

Whether it was sheer luck or the ghost of Nuf-Ced McGreevy assisting the band, each time the Dropkicks played “Tessie” live at Fenway Park during the 2004 playoff run, the Red Sox won as they brought home the first World Series championship to Boston since Nuf-Ced and the Rooters traveled to Chicago singing “Tessie” in 1918. They repeated the feat for the postseason of 2007.

In 2008 Dropkick Murphys frontman Ken Casey and this writer reopened McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon at 911 Boylston Street in Boston in a faithful replica of the original bar with reproduction and original pictures from McGreevy’s original location, including the original painted glass portrait of Nuf-Ced that hung behind the original back bar in Roxbury.

Sadly, in the decade before Glenn Stout’s rediscovery and promotion of the McGreevey Collection, close to one-third of the photographic images that were originally donated to the library in 1923 were wrongfully removed from the Copley Square branch, the victims of a large-scale heist that was perpetrated sometime in the mid- to late 1970s. Amazingly, nearly half of the photographs that were documented as part of the 1939 Filene’s store window display were absent from the Print Department’s holdings. Luckily, library staff had photographed many of images before they were stolen and over the years several of those McGreevy treasures have been recovered. After several items from the collection appeared for sale at local baseball-card conventions and in advertisements published in Sports Collectors Digest in 1983, SABR member Bob Richardson and the Boston Public Library’s keeper of prints, Sinclair Hitchings, conducted an independent investigation and recovery effort that yielded several returns of Nuf-Ced’s stolen treasures.53

In the past few years, other McGreevy gems have appeared for sale on sites ranging from eBay to Sotheby’s, and thanks to additional recovery efforts spearheaded by McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon, some of those rare and historic images have been returned to the institution Nuf-Ced originally donated them to. The most notable recovery was that of the 1904 photograph of John L. Sullivan and Jimmy Collins in the Red Sox dugout. The Boston Public Library stamp on the photograph had been defaced and obscured to conceal its McGreevy provenance but was still visible when it was sold as part of New York Yankees partner Barry Halper’s collection at Sotheby’s in 1999. In 2008 the Boston Globe reported the recovery of the iconic photograph after it was offered for sale online by a dealer in Maine and purchased by the reconstituted McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon. In the article headlined “A Home Run for the BPL,” library official Aaron Schmidt, who had been instrumental in assisting the recovery effort, said, “Every time we get one of these back it’s like a homecoming. Of all the ones that we’re missing this is No. 1 in terms of importance.”54 The photograph was put on display in the museum showcase at the revived McGreevy’s 3rd Base Saloon on Boylston Street.

Author’s note

Over the years there have been several spellings used for both Nuf-Ced’s last name and his nickname (Nuff-Said, Nuf Sed, etc.). Authors Glenn Stout and Don Hubbard have commented on the spelling issue in their books Fenway 1912 and The Red Sox Before the Babe, respectively. Stout chose “McGreevey” based upon several bits of evidence including the 1903 photograph of the 3rd Base Saloon which read: “M.T. McGreevey & Co.” and several listings in the Boston directories and U.S. census records that identified Nuf-Ced as “McGreevey.” Stout was also influenced by the well-established use of “McGreevey” in relation to the Boston Public Library’s collection, which now designates the official name of the collection as the “M.T. McGreevey Collection of Baseball Pictures” in bibliographic records. While Stout also noted that it was common for Irish surnames to have alternate spellings or misspellings, he said, “Irish spellings are often so fluid anyway going from Gaelic to English, but the best part is the whole notion just opens up a little window to another time.”55

When I had to decide what spelling to use for the reconstituted 3rd Base Saloon at 911 Boylston Street, I considered all of Stout’s information as well as additional information available at the Boston Public Library, the Suffolk County Courthouse, and in the U.S. census and Boston directory records. I found that although Nuf-Ced’s birth was recorded with the surname “McGreevey” in the official Roxbury ledgers in 1865, he signed his last will and testament, in 1938, as well as other documents including the lease of his bar property to the library in 1920, as “M.T. McGreevy.” The only surviving photograph of Nuf-Ced in front of his first bar location at 17 Linden Park (circa 1894) shows the name “McGreevy” hand-painted on the business sign. In addition, the vast majority of Nuf-Ced’s baseball advertisements printed on scorecards and programs sold at the Huntington Avenue Grounds bear the “McGreevy” name, including the advertisement for the bar on the cover of the program sold at the first World Series in 1903.

Nuf-Ced may have come into this world in 1865 as a “McGreevey,” but by the time he checked out the flourish from his own pen read: “McGreevy.” As Glenn Stout has said, “Others are free to disagree (after all, in regard to Nuf-Ced, some kind of argument seems wholly appropriate).”56

So, with that being said, both camps have now pounded their fists upon the bar and shouted, “Nuf-Ced.”

This biography can be found in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin. To order the book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also utilized the following sources:

M.T. McGreevey Collection of Baseball Pictures, Print Department, Boston Public Library

The McGreevey Scrapbooks, M.T. McGreevey Collection of Baseball Pictures, Print Department, Boston Public Library

McGreevey Timeline, Glenn Stout, compiler, Print Department, Boston Public Library

Don Hubbard, The Red Sox Before the Babe (Jefferson North Carolina: McFarland, 2009)

Peter J. Nash, Boston’s Royal Rooters (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2005)

Bill Nowlin, Day by Day With the Boston Red Sox (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2006)

Glenn Stout and Richard Johnson, Red Sox Century (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000)

Probate Records of Michael T. McGreevy, Suffolk County Courthouse, Boston.

Glenn Stout, “The Grand Exalted Ruler of Rooter’s Row,” Sox Fan News, August 1986

Don Jensen, “They All Went to Nick’s: High and Low Life in Manhattan’s First Sports Bar,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Spring 2009

Author interview with Alice Thompson, 2006

Author interview with Fran Canario, 2006

Author interview with Glenn Stout for Rooters: The Birth of Red Sox Nation (Cooperstown Monument Co./Killswitch Productions, 2007)

Author interview with John Thorn for Rooters: The Birth of Red Sox Nation (Cooperstown Monument Co./Killswitch Productions, 2007)

Notes

1 McGreevey Timeline by Glenn Stout, M.T. McGreevey Collection, Boston Public Library.

2 Boston Directory, 1887.

3 Boston Globe, clipping undated.

4 Sporting Life, October 2, 1897.

5 “Nuf Ced’s Bar Fond Memory To Sox Attache,” Boston Traveler, undated clipping. Author’s collection.

6 John Drohan, “Nuf Ced’s Bar Fond Memory To Sox Attache,” Boston Traveler, undated clipping. Author’s collection.

7 Boston Traveler, April 23, 1923.

8 Lawrence Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: Macmillan, 1966).

9 Boston Globe, October 12, 1903.

10 Boston Journal, October, 1904. Clipping otherwise undated. McGreevey scrapbook.

11 Boston Herald, October, 1904. Clipping otherwise undated. McGreevey scrapbook.

12 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

13 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

14 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

15 Rooters: Birth of Red Sox Nation (Cooperstown Monument Co./Killswitch Productions, 2007).

16 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

17 Boston Sunday Post, January 19, 1913.

18 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

19 Boston Post, February 1906. Clipping otherwise undated. McGreevey scrapbook.

20 Arkansas Gazette 1906. Clipping otherwise undated. McGreevey scrapbook.

21 Ibid.

22 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

23 Arkansas Gazette, 1906. Clipping otherwise undated. McGreevey scrapbook.

24 Los Angeles Express, February 28, 1911.

25 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

26 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

27 Boston Globe, January 28, 1910.

28 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

29 Baseball Magazine, February 1910.

30 Boston Post, undated clipping in McGreevey scrapbook.

31 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

32 Peter J. Nash, Boston’s Royal Rooters (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2005).

33 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

34 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

35 McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

36 Boston Post (undated clipping) McGreevey Scrapbooks, Boston Public Library.

37 Michael Reiskind and Peter O’Brien, “Boston’s Lost Breweries,” Jamaica Plain Historical Society. March 25, 2006. Transcription posted on the Society’s website.

38 Boston Traveler, April 28, 1923.

39 Letter from Charles Belden to Michael T. McGreevy, May 3, 1923, McGreevey Papers, Boston Public Library.

40 Boston Evening Transcript, April 24, 1923.

41 Boston Post, December 3, 1926.

42 Boston Post, August 21, 1930.

43 Boston Evening Transcript, 1939. Clipping otherwise undated, author’s collection.

44 Glenn Stout, McGreevey Timeline, Boston Public Library.

45 Boston Globe, June 3, 1938.

46 Boston Globe, February 18, 1943.

47 The Sporting News, February 11, 1943.

48 “Nuf Ced’s Bar Fond Memory To Sox Attache,” Boston Traveler, undated clipping. Author’s collection.

49 Ibid.

50 Boston American, May, 1955. Clipping otherwise undated.

51 Author interview with Glenn Stout via e-mail January 2013.

52 “Tessie,” Dropkick Murphys, 2004.

53 Author Interview with Sinclair Hitchings, 2009.

54 Boston Globe, December 31, 2008.

55 Glenn Stout, Fenway 1912 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2012).

56 Ibid.

Full Name

Michael T. McGreevy

Born

June 16, 1865 at Roxbury, MA (US)

Died

February 2, 1943 at Boston, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.