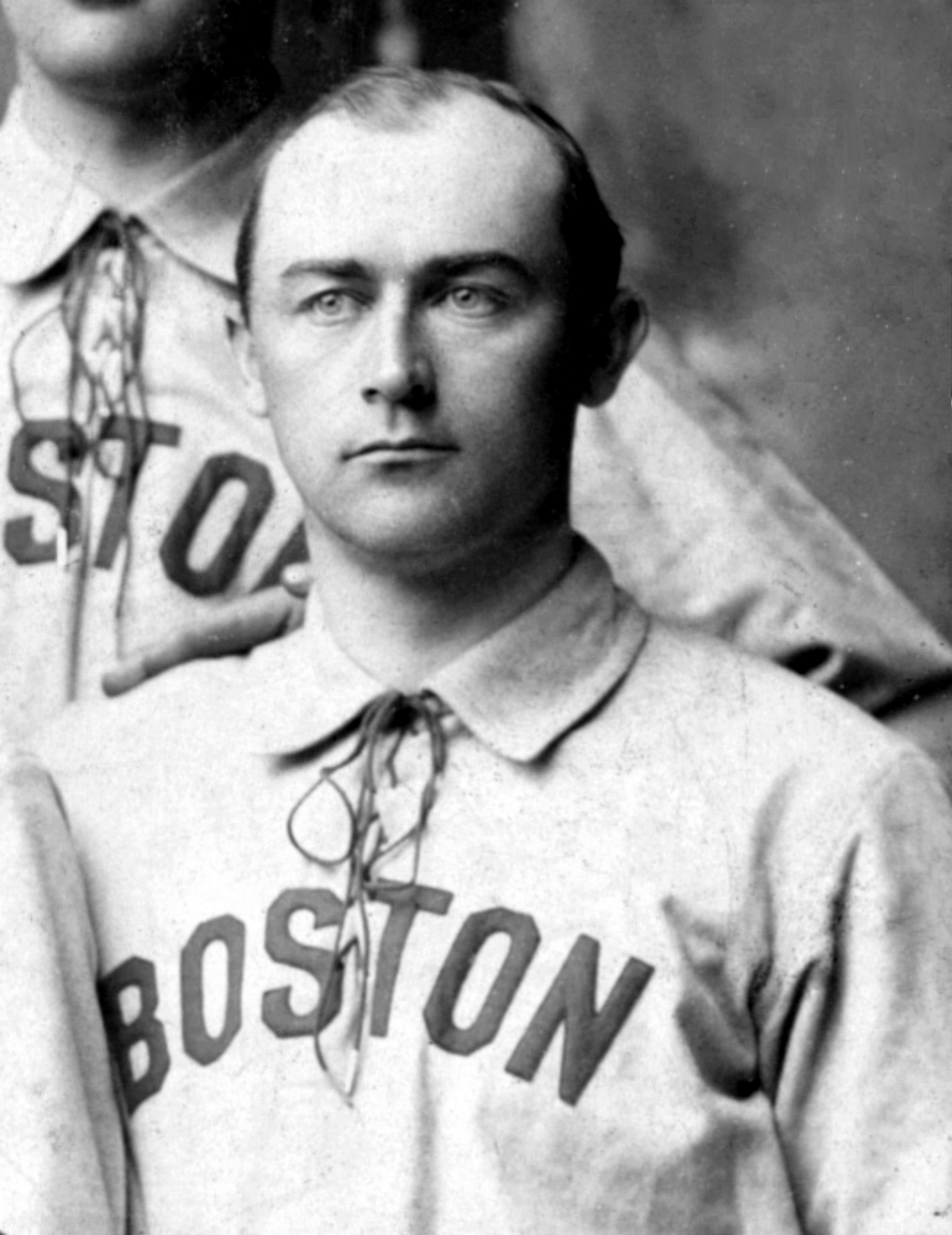

Tommy Dowd

After nine years in the major leagues, Tommy Dowd’s tenth and last season of big-league baseball was with the Boston Americans in the very first year of the new franchise, 1901. This was the team that became the Red Sox. Dowd was, in fact, the first player to ever play for the team, the leadoff batter in the top of the first inning of the Americans’ first game. The game was played at Baltimore on April 26, 1901. Dowd had turned 32 six days earlier. This was Thomas Jefferson “Buttermilk” Dowd, born on April 20, 1869, in Holyoke, Massachusetts. He was the first ballplayer for the franchise who was born in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the only player for the Red Sox clearly named for a United States president. And he played every single game of the 1901 season.

After nine years in the major leagues, Tommy Dowd’s tenth and last season of big-league baseball was with the Boston Americans in the very first year of the new franchise, 1901. This was the team that became the Red Sox. Dowd was, in fact, the first player to ever play for the team, the leadoff batter in the top of the first inning of the Americans’ first game. The game was played at Baltimore on April 26, 1901. Dowd had turned 32 six days earlier. This was Thomas Jefferson “Buttermilk” Dowd, born on April 20, 1869, in Holyoke, Massachusetts. He was the first ballplayer for the franchise who was born in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the only player for the Red Sox clearly named for a United States president. And he played every single game of the 1901 season.

Dowd, the left fielder, led off that first game by grounding right back to the Baltimore Orioles’ pitcher, Joe McGinnity, and was thrown out at first base. He was 1-for-5 that first day, singling in the top of the eighth and driving in Lou Criger. Boston lost the game, 10-6. Dowd also had the first stolen base for the new team. There were no thefts in the first two games, but Dowd walked and stole second in the first inning of game No. 3, on April 29, 1901, then stole third and scored on a bad throw to third – all before the second batter completed his at-bat.

In Boston’s first home game, played on May 8 at the Huntington Avenue Grounds, Dowd earned a number of firsts. He was the first batter to play before the home crowd, and he got the first hit in Boston, a first-inning leadoff single to left field. He was sacrificed to second, and scored the first run when Jimmy Collins drove him in with a single. The final score of the game was 12-4 over the Philadelphia Athletics.

Dowd played Brown University baseball from 1888 to 1891. A brief article in the March 6, 1891, Boston Globe said that “T. J. Dowd, second baseman of the Brown University team, has been signed by the Boston Athletic Club team.” This was the American Association team known as the Boston Reds, not to be confused with the National League’s Boston Beaneaters. The American Association approved the contract the next day. Dowd played his first game for the Reds in Baltimore on April 8, in front of 5,000 fans. The Reds played under manager Arthur Irwin. Dowd “made a beautiful running catch in the ninth inning, for which he got a round of cheers.”1 He played right field and batted ninth, after the pitcher. He was 1-for-4 and scored a run, but Baltimore won, 11-7. The Brown Alumni Magazine wrote that the Globe’s Tim Murnane had called him “the best center fielder he’d ever seen, especially for his skill at sprinting back on a ball over his head and then turning left or right for the catch. For years Dowd held the unofficial record time for circling the bases.” He was fast; he stole 366 bases during his years in the majors.

Dowd also attended other colleges as well, and studied law at Georgetown. In that 1891 debut season, he appeared in four games for Boston with just the one hit and the one run, in 11 at-bats. He was then sold (or loaned) to the Washington Nationals. Dowd was a hit in Washington. The April 27 Boston Globe quoted the Washington Post: “Tommy Dowd owns the town, and can have all the earth but Italy for the asking.” He’d gone from the team that finished first – the Reds – to the team that wound up finishing last. He was the Senators’ regular second baseman, appearing in 112 games. His .259 was a few points above the team average. Dowd played in 1892 for Washington as well, getting into 144 games and hitting .243. This time, his average was four points above the team’s. He was released in November and was signed on December 1 by the St. Louis Browns, for whom he played the next four-plus seasons. The release and sign appears to have been part of a prearranged deal; the August 6, 1989, issue of Sporting Life wrote that St. Louis executive Chris Von der Ahe had seen Dowd in action and after “becoming stuck on his playing, bought his release from Washington.” But by mid-1898 he was seen to have “retrograded rather than advanced.”

Beginning in 1893, the National League was a 12-team league. Dowd was never on teams finishing in the top six. His batting average fluctuated from .282 in 1893 (when he mostly played left field) to .271 (1894, when he was the right fielder) to .323 (right field) to .265 (back to his original position at second base). His best year without a doubt was 1895 (the .323 season), when he drove in a career-high 74 runs.

The Browns were a team that had managerial instability, to say the least. Bill Watkins was the skipper in 1893 and Doggie Miller was in 1894. There were four managers in 1895: Al Buckenberger, Chris Von Der Ahe (for one game), Joe Quinn, and Lou Phelan. The 1896 team topped even that, with five managers: Harry Diddlebock, Arlie Latham (three games), Von Der Ahe (two games), Roger Conner (under whom the team was 8-37), and Tommy Dowd, who oversaw 25 wins against 38 defeats. Dowd’s work was regarded highly, at least at first, in Sporting Life. The August 15, 1896, issue saw a “great improvement” in the team during his first couple of weeks on the job. “Roger Conner as manager lacked firmness,” the publication opined. “There is none of that nonsense now. Dowd, in addition to being a tip-top ball player, has a good head. He has taken advantage of his opportunity and possesses an education above the average. It was Dowd’s original intention to become a lawyer. His studiousness now stands him well in hand.”

Dowd was the first of four managers in 1897. “He Will Hustle Hard to Keep the Browns out of Last Place” was the subhead in a March 20 Sporting News article titled “Tommie’s Task.” It was, the paper added, “a task that would dismay many men.” In fact, it did. The Browns posted a record of 6-22 before Dowd was relieved of his duties, surrendering them to Hugh Nicol. After appearing in 35 games, Tommy was traded on June 1 to the Philadelphia Phillies for Bill Hallman, Dick Harvey, and the princely sum of $300. He finished the season, batting .292 to the .262 he’d hit for St. Louis, reverting back to right field. On November 10, the Phillies traded him back to St. Louis, but as part of a much larger trade, one involving two played named Cross going in opposite directions: Lave Cross, Dowd, Jack Clements, Jack Taylor, and $1,000 was the package for the Browns, who swapped Monte Cross, Red Donahue, and Klondike Douglass.

Dowd played second base in 1898, hitting .244 – just three points below the team average. The Browns finished last in the league standings. He stayed with St. Louis until March 29, 1899, when he was part of a group of 15 players assigned to the Cleveland Spiders. (The St. Louis club had gone into receivership and the assets were sold at a sheriff’s auction for a sum in excess of $70,000. The sale included all the stands of Sportsman’s Park and the lease held on the ground, and a number of ballplayers.)2

The team in St. Louis changed its name to the Perfectos. On March 29, the following ballplayers were all assigned to the Cleveland Spiders: Kid Carsey, Jack Clements, Lave Cross, Dick Harley, Bill Hill, Jim Hughey, Harry Lochhead, Harry Maupin, Joe Quinn, Jack Stivetts, Willie Sudhoff, Joe Sugden, Suter Sullivan, Tommy Tucker, and Tommy Dowd.

The Perfectos did improve as a team, reaching fifth place. The Spiders finished last, with the unbelievably bad record of 20-134, finishing 84 games out of first place. Their center fielder, Dowd, scored a team-leading 81 runs, batting .278, but drove in only 35 runs. He led the team in stolen bases with 28.

Dowd was out of the majors in 1900, working for more lucrative pay at a laundry business in Holyoke, then playing for Chicago and Milwaukee of the American Association, which by then had reverted to minor-league status. On March 29, 1901, Dowd signed with the Boston Americans and returned for the one final year.

Holyoke was his home. He was born there and he died there. He is buried there at Calvary Cemetery. Both parents had come to the United States from Ireland. Jeremiah Dowd was a brick mason or bricklayer (he used both terms) and did some farming. His wife, Mary (Lynch) Dowd, was listed in the 1870 Census as “keeping house.” It would have been a full-time job. At the time of that year’s census, when Tommy was 1 year old, he had older brothers Michael, John, Jeremiah, and Eddie, and an older sister, Mary. But the Dowd parents weren’t finished yet. After Tommy was born, they added Kate, Lawrence, and Theresa to the Dowd brood. Michael and John became bricklayers, too. Mary became a dressmaker and Theresa a schoolteacher. Thomas became a professional ballplayer.

He was right there at the beginning of franchise play, on April 1, 1901 when Jimmy Collins and 11 members of Boston’s brand-new American League club began their first workout of their first spring training, at Charlottesville, Virginia, with two hours of light practice on the grounds of the local YMCA. Collins, Stahl, Freeman, Dowd, Hemphill, Schrecongost, Jones, McLean, Mitchell, Kane, McCarthy, and Connor joined in the session. Cuppy, Criger, Parent, Ferris, Kellum, and McKenna reported the following day. Perhaps the first sign of exceptions for Red Sox superstars was set – Cy Young was training in Hot Springs and due to report on Opening Day in Baltimore.

Dowd had a standout game in the second spring training game, a 23-0 win over the University of Virginia nine on April 11. It was only the second game the team ever played. Tim Murnane covered spring training for the Globe and it’s likely he who wrote the account: “Everyone but Hemphill hit the ball. Ferris led with a home run and two singles. Close behind came Parent, with two screeching doubles and a single, and Dowd with four singles. Collins lifted the leather over the palings, besides singling.”

Dowd’s last major-league games were both on September 28, 1901, in the final day’s doubleheader. He was 1-for-5 and 2-for-3. For the season he batted .268 – close to his .271 career mark – with three home runs and 52 RBIs. Boston wrapped up the first year of the franchise with two high-scoring wins over Milwaukee, 8-3 and 10-9. (Jack Slattery, the only Boston native playing for the Americans that year, made his major-league debut as Boston’s catcher in the first game. He went 1-for-3, and then was injured in the eighth.) Dowd homered for Boston in the first game. The second game perhaps didn’t offer the best competition. “Both pitchers worked wretchedly,” wrote the Washington Post. Manager Jimmy Collins hit two homers for Boston, but it was Hobe Ferris who won it in the bottom of the seventh with a two-run triple. Then the umpire (games in this era often had just one), Tommy Connolly, called the game due to darkness. Boston wound up the year with a six-game winning streak but finished four games behind the first-place White Sox. They drew three times as many fans as the Boston Nationals. The team that would become the Red Sox was here to stay.

Tommy Dowd had aspirations for 1902 and applied to the National Association for a franchise in Milwaukee but his request was referred to committee.3 He went to the minor leagues in 1902, playing for the snappily-named Amsterdam-Gloversville-Johnstown Jags (in the Class B New York State League). There was a method to his seeming madness, though: He owned the club, and also managed it. And batted .287 in 404 at-bats, and 94 games. Alas, the team finished last, 29-72.

The next year Dowd played for two clubs – 55 games with the Baltimore Orioles in the Eastern League and 33 games as player and sometime manager in Nashua, New Hampshire – a team without a name. One of his fellow outfielders was Moonlight Graham. With the Orioles he played under two future Hall of Famers, Wilbert Robinson and Hugh Jennings, and hit .228. In Nashua, B-level ball in the New England League, he hit .276. He was busy in 1904, too, but without any extra duties, playing Class B ball for both the New Orleans Pelicans (Southern Association, 30 games, .256) and then, right in his own hometown, the Holyoke Paperweights (Connecticut State League, 82 games, .241).

In the spring of 1905, Dowd coached the Williams College baseball team in Western Massachusetts during the school year, then managed in Burlington, Vermont, the rest of the year.

In 1906 and 1907 he returned to the Paperweights, as player-manager, running the team for part of 1906 (and hitting .270) but hitting only .216 in his final year as an active player. Though not successful at the plate, he led the 1907 team to the Connecticut State League pennant.

The next three seasons, Dowd managed exclusively. He raised hopes in Hartford in 1908, assuming the reins there. George E. Cox wrote before the season got under way, “The players, upon reporting, will be given a ‘treatment’ in the Dowd method which has been so successful in other cities where applied in the past. No laggards, says Dowd, will be tolerated on the team. He adds that he will demand that every player give his best efforts, but will not ask anything more than he is willing to do himself. The fans in this city like this sort of talk.”4 He didn’t last the year as manager.

In 1909 and 1910, Dowd managed the New Bedford Whalers of the New England League, placing sixth the first year (after coaching at Williams again) and winning the League pennant the second. In March 1911, he was involved in a controversy regarding a case of farming player George Walsh between Boston’s National League team and the Whalers, which the National Commission found objectionable, adding in its report, “This is but one of many violations of the laws of organized base ball by the New Bedford Club within the past year. The same unlawful and irregular tactics were employed by its offices in the Temple and Ulrich cases.”5

Dowd and Organized Baseball parted company, but Tommy kept busy, coaching independent baseball teams, Williams College, and Amherst College, too. Among the players he is credited with discovering were Chick Evans and Rabbit Maranville.

On July 2, 1933, the body of a man was found in the Connecticut River near Holyoke. Two days later, Dowd’s brother Jeremiah identified the body as that of Thomas Dowd. The death certificate ruled his death as due to accidental drowning.

He was single and had been retired since December 1914. He is said to have “fallen upon unfortunate days” for some unspecified period of time prior to his death.6

This biography can be found in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin. To order the book, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Boston Globe, April 9, 1891.

2 Boston Globe, March 18, 1899.

3 Sporting Life, January 25, 1902.

4 Sporting Life, April 25, 1908.

5 Sporting Life, March 25, 1911.

6 Hartford Courant, July 6, 1933.

Full Name

Thomas Jefferson Dowd

Born

April 20, 1869 at Holyoke, MA (USA)

Died

July 2, 1933 at Holyoke, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.