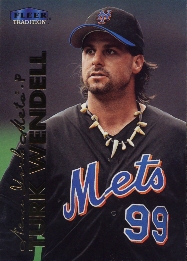

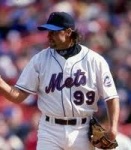

Turk Wendell

The heir to Moe Drabowsky, Tug McGraw, and Roger McDowell, Turk Wendell kept the tradition of lovable zany relievers alive. Wendell had a unique litany of on-field antics, plus a trademark necklace of animal teeth and claws – from beasts he’d hunted himself. “Turkey spurs too,” said the avid outdoorsman, “but no shark teeth.” Yet Wendell was also an effective and busy fireman, with a hard slider and a rubber arm. The righty appeared in 552 big-league games from 1993 through 2004, and he was always willing to challenge hitters.

The heir to Moe Drabowsky, Tug McGraw, and Roger McDowell, Turk Wendell kept the tradition of lovable zany relievers alive. Wendell had a unique litany of on-field antics, plus a trademark necklace of animal teeth and claws – from beasts he’d hunted himself. “Turkey spurs too,” said the avid outdoorsman, “but no shark teeth.” Yet Wendell was also an effective and busy fireman, with a hard slider and a rubber arm. The righty appeared in 552 big-league games from 1993 through 2004, and he was always willing to challenge hitters.

Steven John Wendell was born on May 19, 1967, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. This small city is the seat of Berkshire County, which forms the western part of the state. Wendell was the third of six children. He had a brother named Charles and four sisters, Audrey, Tricia, Terri, and Debra. His father, Charles D. Wendell, was an auto-body technician by trade. At other times, though, he worked as a foreman for General Electric (long the biggest employer in Pittsfield) and owned and operated a variety store. Turk’s mother, Beatrice, was a homemaker.1

The Wendells lived in the town of Dalton, which borders Pittsfield to the east. Another righty reliever, Jeff Reardon, had grown up there about a dozen years before. Reardon, who reached the majors with the New York Mets in 1979, was one of young Turk’s heroes. It’s little surprise, though, that Wendell was a huge fan of the Boston Red Sox. His favorite player was Carl Yastrzemski.2

Turk got his nickname at the age of 3. By one account, the little boy repeatedly jumped face first from a window into a mound of snow made by his grandfather. The man said, “That was something only a Turk would do.”3 In 1991 Wendell himself clarified: “My grandfather nicknamed me after one of his buddies because I was always doing stupid, rebellious things.”4 “He wrecked everything in no time at all,” said his father. “He always thought he was indestructible. He always has been a daredevil.”5

Whenever the subject of baseball superstition comes up, Wendell is inevitably singled out as an extreme example. For him, though, the preferred label is “routine” – something that puts human beings, who are habitual by nature, in a comfort zone.6 Even when he was in Little League, this was evident. He wore the same Dallas Cowboys shorts under his uniform until “2,000 or so washings kind of wore them out.”7

“I’ve wanted to be a baseball player ever since I could remember,” Wendell said in 1992. “I used to tell my friends that I would play in the big leagues, and they used to tell me to grow up.”8 He continued to pursue his goal at Wahconah Regional High School in Dalton, where Jeff Reardon had also gone.9 Though he also played some third base and shortstop as a schoolboy, pitching was where Wendell stood out. In his senior year, 1985, he was a member of the All-Western Massachusetts baseball team. He threw three no-hitters that season.

Wendell then went to Quinnipiac College in Hamden, Connecticut (near New Haven). The longtime coach at Quinnipiac, Dan Gooley, recruited him. When asked if he had any offers from bigger schools, Wendell responded, “Nope, nothin’ else.”

Looking back in 2012, Gooley viewed Wendell as one of the most talented players in the program’s history (there had been more than 20 other pros, but no other Bobcat had made it to the majors as of 2014). Even then, Turk was known for his behavior – he quoted his father, “If he [Charles] was the other team, he’d ask for a drug test or a mental exam.” Coach Gooley said, however, “None of it was an act. … Everything about him was legitimate. He was the most loyal, honest person I’ve ever met. He wasn’t showing people up. That’s just who he was.”10

Wendell also played summer ball while he was in college, for the Falmouth Commodores in the Cape Cod League (1987). Previously, while on vacation from Wahconah, he had been with the Dalton Collegians, a strong semipro team.

As a college junior in 1988, Wendell was 5-3 with 66 strikeouts in 62 innings.11 He was a second-team All-New England selection. Quinnipiac won the Northeast-10 Tournament and earned a berth in the NCAA Division II tournament. During that tourney, Wendell pitched 15 innings against Mansfield University in one game.12

The Atlanta Braves chose Wendell in the fifth round of the amateur draft that June (he eventually graduated in 1999 with two associate degrees, in science and liberal arts). When he signed, it was in his contract that he be given the uniform number 13.13 Throughout his pro career, until he joined the Mets in 1997, he wore it unless it had already been issued to someone else. In his early years, he had a different necklace featuring a glove with a cross and the number 13 inside.

During most of Wendell’s time in the minors, he was a starting pitcher. His first pro season wasn’t impressive on the surface: 3 wins against 8 losses, with a 3.83 ERA for Pulaski of the Appalachian League (rookie ball). He did strike out 87 batters in 101 innings, though, while walking only 30. He had six complete games in 14 starts.

In the minors, Turk quickly gained attention for the many elements of his routine. Among the most notable:

- Bounding over the foul line as he approached and left the mound. “In high school, I stepped on the foul line when taking the field, I gave up some runs that inning,” Wendell said in 2009. “From that point on I never wanted to step on the foul line again.”14

- Squatting on the mound until his catcher squatted. Turk would then rise and begin to warm up. He and the catcher could never be standing or squatting at the same time.15

- Drawing three crosses in the dirt on the mound. “The crosses are for the three prayers I pray,” said Wendell, who read the Bible nightly. “I pray out there to do the best of my ability. … I pray to be injury free, and I pray to win.”16 He followed by licking the dirt off his finger.

- Waving to the center fielder before his first pitch. The center fielder had to wave back. This little custom also dated back to Wahconah, where the player behind him was future big-league executive Jim Duquette.

- Chewing black licorice and brushing his teeth between innings. The clean-living Wendell didn’t want to chew tobacco – in fact, he noted in 2010 that he had never tried tobacco in any form or had even a sip of alcohol.17 “Or any drug,” he also emphasized. The tooth-brushing was a direct consequence of the licorice and his desire for dental hygiene. “I don’t like the way licorice makes my teeth feel. It just sits there. I don’t want my teeth to get stained.”18

- Not wearing socks. “Socks don’t serve a purpose. They’re useless.” He wouldn’t put on a pair even for his sister’s wedding.19 The lack of socks was a factor in his later switch to high-top shoes.20

- Insisting that the umpire roll the ball back to him. If an umpire did throw him the ball, Wendell watched it go by or took it off the chest. Then he picked it up.21

“If I find something that works for me I stay with it no matter how crazy it may seem,” Wendell said in 1991. “Sometimes I would rather not be [driven by routine], but that’s the way I am.”22 The following year, he observed, “People used to compare me all the time to Mark Fidrych, with the way he’d talk to the ball and everything. I used to resent it, because I thought he did it for a show. This spring, someone who knew Mark told me that he was really that way, that it was not an act. That made me respect him a lot, with the way he was and the success he had.”23

Another parallel in this regard was Kevin Rhomberg, the infielder-outfielder who played briefly with the Cleveland Indians in the early ’80s. Rhomberg’s rituals were possibly even more involved and intricate than Wendell’s. But while the players were perceived as eccentric, they were at root happy family men.

Though it wasn’t his choice, Wendell discarded much of his routine over the years. To the end, though, he kept on leaping over the foul line. He also added a new wrinkle in 1997, slamming the rosin bag down on the mound with gusto after finishing his warm-ups. “I started it … out of frustration and motivation,” he said in 1999. “It’s drama. Animation.”24 He later noted, “It had nothing to do with the fans. It was not for them but self-motivation.” Nonetheless, the Shea Stadium crowd ate it up.

Turk split most of 1989 between two Class A teams, Durham of the Carolina League and Burlington of the Midwest League. He also got into one Double-A game with Greenville of the Southern League. Overall, he was 11-11 with a 2.22 ERA, thanks to five shutouts. He struck out 183 in 186⅔ innings.

During his third year in the minors, Wendell had to adjust. He spent most of the 1990 season with Greenville, but had a tough time, going 4-9, 5.74 in 36 games. He relieved in 23 of those outings, marking the first time he had shifted to the bullpen. “I got out of sync with knowing my body,” he said, also noting that he had elbow tendinitis. “Being competitive, I was very stupid. I was going out there when I was hurting, and it was taking its toll on me. But after Instructional League, I rested my arm, monitored it. My arm got stronger, and I carried that from the offseason right up through spring training. Plus, I was in spring training with the big-league team. It made me real hungry.”25

Wendell’s work ethic was always strong – he ran 10 miles to the park on days when he was not pitching. But with his mental energies refocused, he rebounded sharply in 1991. He posted marks of 11-3, 2.56 for Greenville – where thousands of fans lined up at the ballpark well before the gates opened on days that he pitched.26 He was mainly a starter again, relieving just five times in 25 appearances. He started for the National League team in the Double-A All-Star game that year.27 Later he moved up to Triple-A Richmond for the first time, making three starts.

Near the end of the 1991 big-league season, Atlanta traded Wendell and Yorkis Pérez to the Chicago Cubs for Damon Berryhill and Mike Bielecki. Turk then went to play winter ball in Puerto Rico for the Santurce Cangrejeros. In his book about the Crabbers, author Thomas Van Hyning wrote that Wendell’s mound antics “had Santurce fans calling the team’s office to find out when his next start would come.”28 Wendell himself remembered, “They would not allow me to pitch road games – only at home!”

Wendell pitched very well for the Crabbers. He started the 1991-92 season with a 1-0 shutout against San Juan, and he finished with a sparkling record of 7-1, 0.94 in 67 innings. Though Gino Minutelli edged him out for the best ERA at 0.90, Turk won the Juan Pizarro Award as the Puerto Rican league’s outstanding pitcher – it so happened that Pizarro himself was Santurce’s pitching coach. Van Hyning wrote, “Wendell got hitters out with a change-up and his 85-89-mile-per-hour fastball. [Manager] Mako Oliveras felt that Wendell’s high leg kick and rapid delivery were his strong points.”29 Van Hyning’s estimate of Turk’s fastball was low; he could reach the low 90s.

Turk remained a starter in the Cubs chain from 1992 through 1994 with their Triple-A team, Iowa. He pitched just four games in 1992, owing to a stress fracture in his elbow, which required a cast.30 The Sporting News noted that February that Wendell had come back from Puerto Rico with arm problems, viewed as minor at that point.31 Upon his return, Wendell was a candidate to join the Chicago rotation in 1993, but he returned to Iowa. That June, though, despite not pitching especially well (5-4, 4.47), Wendell was called up to the majors for the first time amid a rash of injuries to the Cubs’ starters.32

Turk made his debut on June 17 at Wrigley Field. Although the Chicago fans enjoyed his routine, the St. Louis Cardinals knocked the rookie out of the box in the fourth inning. “Only a couple of doubles,” he recalled. “No home runs.” Five days later, he got the hook in the second inning against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Three Rivers Stadium. He took the loss in both games. Wendell got one more start, at San Diego on June 28, and pitched much better, giving up just two earned runs on six hits in 7⅓ innings (the Cubs won in 11). He was then optioned to Iowa, but returned for four more games in September and October, getting his first big-league win – again at San Diego – on the last day of the season. He took a no-hitter into the sixth inning and gave up just one run in seven innings.

Wendell had a much better year at Iowa in 1994, going 11-6, 2.95 in 23 starts. He made six scattered – and largely ineffective – appearances with the big club from late April through mid-June. These included his last two starts in the majors. One of his 1997 baseball cards carried a quote from Turk on his change in role: “If you pitch bad as a starter, you go to the bullpen. If you pitch bad as a reliever, you go home.” Though he was well suited to the job – he always wanted to take the ball – he said, “I was a relief pitcher by default.”

The big-league strike of 1994 carried over into early 1995. Spring training was abbreviated, and Wendell reportedly had a little shoulder soreness – “a made-up injury to buy time to make roster moves.” So that May, he was assigned to extended spring training, doing a ten-day stint with Daytona (a high Class A team), followed by a short stretch with Orlando (Double-A). Chicago recalled him in late May and he went 3-1, 4.92 in 43 games. At the end of August, however, he passed through waivers – and went unclaimed – as the Cubs did some roster maneuvering.

In 1995 Cubs manager Jim Riggleman also asked Turk to “knock off his superstitious idiosyncrasies. ‘I asked him not to let it be an issue,’ Riggleman said, ‘that he should be recognized … by what he does from 60 feet, 6 inches. If he needs to do those things, do them out of sight of the camera.’ Said Wendell: ‘I did them to make the game fun, [that was] all. I’ll just have to think of other ways to have fun.’”33 The word also came down from new club president Andy MacPhail and general manager Ed Lynch. Wendell questioned the need for what he called “a major adjustment,” but went with it philosophically.

Riggleman, a self-described “staunch, conservative old-timer,” also cracked down on an earlier version of Turk’s wildlife necklace, saying, “It puts the wrong picture on the game.”34 Daytona sportswriter Sean Kernan had noted that baseball was already in short supply of colorful characters.35 Yet even the watered-down Wendell was still a more distinctive personality than just about anyone else in the game.

Riggleman, a self-described “staunch, conservative old-timer,” also cracked down on an earlier version of Turk’s wildlife necklace, saying, “It puts the wrong picture on the game.”34 Daytona sportswriter Sean Kernan had noted that baseball was already in short supply of colorful characters.35 Yet even the watered-down Wendell was still a more distinctive personality than just about anyone else in the game.

After 1995, Chicago’s closer for three seasons, Randy Myers, signed with the Baltimore Orioles as a free agent. Doug Jones didn’t work out as the replacement for Myers, and the Cubs gave Wendell a chance to earn saves. He responded with a career-high 18 in 70 appearances in 1996. His ERA was 2.84 and he struck out 75 men in 79⅓ innings. First baseman Mark Grace said, “The best thing that ever happened was ‘Rigs’ telling him to tone it down. That way he could concentrate on getting hitters out.”36

In December 1996, however, Chicago signed Mel Rojas to be the closer. Rojas had posted 36 saves for the Montreal Expos that season and 30 the year before. After some experiments in camp with a return to the rotation, Wendell went back to being a setup man. As it developed, the Cubs traded both him and Rojas, along with center fielder Brian McRae, to the New York Mets, who had hopes of earning a wild-card spot and wanted to strengthen their bullpen. Rojas had not pitched well for Chicago – but he was dreadful in his season and a half with the Mets. McRae had a pretty good year in 1998, but New York dealt him away in July 1999. Wendell turned out to be the most valuable asset they acquired.

When Wendell joined the Mets, number 13 was not available – Edgardo Alfonzo was wearing it. Instead, he asked for number 99. It’s often thought that this was an homage to the Charlie Sheen “Wild Thing” character in the movie Major League, but in 2000 Turk said that was not the case – he simply thought it was cool.37

The number became a running theme. In both 1999 and 2000, when Turk signed contracts with the Mets, he insisted that the amount end in 99 cents. “I love 99, so why not?” he said the first time. “I want to have as many 99s in my contract as possible. It has to give me good luck.”38 In December 2000, he signed a deal that had total value (if all incentives were reached) of $9,999,999.99. “It was all my agents’ doing for publicity,” Wendell later recalled.39

Wendell had wanted to play one year of that deal for free, but baseball’s collective-bargaining agreement prevented him from doing so. “That’s still definitely in my hopes and dreams,” he said. “A lot of players, we’d be playing this game if we got paid or not. I have the most fun when I’m playing the game of baseball. A lot of the monkey business and other things going on, I don’t care for.”40

From 1998 through 2000, Wendell averaged 74 appearances per season with the Mets. He set a club record by appearing in nine straight games from September 14 through September 23, 1998. In support of closer John Franco, he formed a strong middle-relief combo with lefty Dennis Cook; here and there both got the occasional save. Turk got into 80 games in 1999, breaking the club record of 76 held by Jeff Innis.41 He appeared for the first time in the postseason that year, working in seven games. He got a win in the National League Division Series against Arizona and another in the Championship Series against Atlanta.

During that offseason, Wendell had quite an adventure while hunting (he got his great love of hunting, fishing, and archery from his father). While pursuing a mountain lion in the Rocky Mountains, he and his guide got too far from their car and wound up staying out overnight in Pike’s Peak National Forest in severe cold. The New York Post wrote that it was 10 degrees below zero, but Wendell said it was really 17 below. In best Jack London style, the men built a fire and walked out the next morning. Mets spokesman Jay Horwitz said, “Turk is, in his words, ‘a master camper.’” Wendell added, “I’m as at home in the woods as I am on the baseball diamond.” His only concern was for his wife, Barbara, who was eight months pregnant with their second child.42

The Mets won the NL pennant in 2000, and Wendell appeared in 77 games (8-6, 3.59). He worked in two games in each round of the playoffs, with a win against St. Louis in the NLCS. He then pitched twice more in the World Series, losing Game One to the Yankees in the bottom of the 12th – “after warming up six times prior to getting in the game.”

Going into the Series, Wendell had said, “Yankee Stadium? I don’t give a hoot about it. We’ve played there before. It won’t be a surprise.” Speaking as a Red Sox fan, he added, “The Yankees have tortured us for years and years, and beating them would be sweet for me.”43 He put it even more strongly in another interview: “It’s almost like a personal vendetta of mine that I can do my part as a Red Sox fan and for all the other Red Sox fans, to knock them off.”44

After the Bronx Bombers won in five games, strength trainer Brian McNamee – who became best known for his role in the Roger Clemens doping scandal – said, “They [the Mets] might have had a chance if he [Wendell] didn’t open his mouth. Oh, he pissed everybody off.” In their locker-room celebration, the Yankees issued multiple toasts, “To Turk Wendell!”45

That winter Wendell turned down offers from the Cubs and Orioles to stay with the Mets. Even though he could have made upwards of $4 million more, he wanted to show his loyalty to the club and the fans of New York.46 During the World Series he had expressed disappointment in Clemens because the former Red Sox ace had signed with the Toronto Blue Jays in 1996. Wendell said, “A guy of that stature should think of loyalty first, not money.”47

Wendell remained busy in 2001. He appeared 49 times for the Mets and 21 times more for the Philadelphia Phillies after he was traded, along with Dennis Cook, for two pitchers, Bruce Chen and minor leaguer Adam Walker. Manager Bobby Valentine said of Turk and Cook, “You know they’re going to be missed. … They took the ball every day and they’re terrific people.”48 In particular, Wendell was well known for his work on behalf of charities (though he preferred to go about it quietly) and willingness to do meet-and-greet appearances with fans (notably, readings for children).

After having won the pennant the year before, the Mets were struggling, 10 games below .500. General manager Steve Phillips said that New York was “looking for guys close to the big leagues who could step in and help this year and next year.” Years later, Chen became a serviceable big-league starter, but his brief stay with the Mets was unmemorable. Walker made it only to Triple-A, and that for just one game.

Wendell’s elbow had bothered him greatly after he was traded to Philly, and he wound up missing all of the 2002 season. He tried a bullpen session in May, but there was still too much pain, and he underwent surgery. His flexor tendon was torn from the bone; in 2009, he observed, “The injury came about over time. Overuse was the main factor.” After rehabbing – “biblically,” as he put it49 – Turk started the 2003 season on the disabled list. He threw six scoreless innings in a minor-league rehab stint and felt pain-free, so the Phillies activated the veteran in mid-April. He declared, “If I wasn’t ready, I wouldn’t be here. I’m anxious to go after sitting out my red-shirt season.”50

Wendell went on to pitch in 56 games in 2003 with pretty good results (3-3, 3.38). He did not return to Philadelphia, though. In January 2004 he signed a minor-league deal with the Colorado Rockies, for a much-reduced salary of $700,000. He had a seven-figure offer from the Chiba Lotte Marines in Japan, managed by Bobby Valentine. The Japanese fans would probably have loved him, as they did another old Mets teammate, Benny Agbayani. For Turk, however, the Rockies were an attractive option because he had made his home in Colorado for several years and had promised his family he’d be with them. “I turned down a guaranteed $900,000 from the Marlins to go home to Colorado,” he said.

Wendell made the Rockies roster but got into just 12 games during April and May, posting a 7.02 ERA. He went on the disabled list, this time with a sore shoulder – “another made-up injury. I just sucked or was sucking at that point.” In June, he went on a rehab assignment to Triple-A Colorado Springs, but he was ineffective in 12 games there. Colorado released him near the end of July.

At the age of 37, Wendell gave it one more try, signing a minor-league deal with the Houston Astros in January 2005. His shoulder was reportedly troubling him, though, and he gave up eight runs in 6⅓ innings during spring training. After the Astros reassigned him to minor-league camp, he retired. “It was never stated or announced.”

Wendell finished with a career record of 36 wins, 33 losses, 33 saves, and a 3.93 ERA in 645⅔ innings pitched. His career WHIP (walks plus hits per inning pitched) was 1.4, he allowed just 30 percent of inherited baserunners to score, and he allowed 73 home runs. Because Turk was never afraid to challenge hitters, sometimes that meant he’d give up the long ball. When asked whom he respected most among enemy batters, he replied “The no-name players, call-ups.”

Perhaps the most interesting sign of Wendell’s approach on the mound was his success against Mark McGwire. When McGwire came to the National League in July 1997, he was at the peak of his home run prowess. Big Mac faced Wendell 11 times – and didn’t get a single hit, while striking out six times. Turk also intentionally walked him just once. “I was lucky, he missed some good pitches,” said Wendell. “He must not have been able to see the ball off me very well.”

Turk also made it a point to say, “Look up my stats against Andruw Jones.” Indeed, Atlanta’s star center fielder was 0-for-22 against Wendell, with just two walks.

Another intriguing little note from Wendell’s career regards his skill in the old fake-to-third, throw-to-first pickoff. He perfected it in the late 1990s, in response to a challenge from his pitching coach, Bob Apodaca, who told him that his third-to-first move was horrible.51 He made the play successfully quite a few times over the years – “two in the same inning once!”52 A rule change in 2013 outlawed this maneuver, however; it is now called a balk. Turk’s response: “Bulls**t! Why change the game?”

After retiring, Wendell – “baseball’s Jeremiah Johnson,” as Kevin Kernan of the New York Post described him – ran a 200-acre hunting and fishing property called Wykota Ranch in Larkspur, Colorado. He enjoyed his favorite pursuits – bow hunting, fishing, and trapping – while raising crops and farm animals. Various kinds of gamefowl roam the land.53 He and Barbara (maiden name McLoone) got married on February 1, 1997. They had a daughter named Dakota and a son named Wyatt, but got divorced in 2009.

Wendell continued to hold forth on the business of baseball. He had two central topics. First and foremost, he remained vehemently opposed to steroids. One example came shortly after signing with the Rockies, when he told the Denver Post that it was “clear just seeing his body” that Barry Bonds had been taking them. In talking with Kernan, he called out McGwire and Alex Rodriguez for what he felt were disingenuous statements. He also reiterated his belief that the major leagues should have a worldwide draft.54

Kernan concluded, “Wendell doesn’t offer lip service. He speaks directly from his heart.”55 Looking back, Turk remarked, “Ambush – never an interview! We were just shooting the breeze, he had a tape recorder in his pocket without consent!” Nonetheless, Wendell always stood behind his words and backed them with deeds. Among other things, he showed his proud support of the American military.56 “I went on three tours to visit troops in Afghanistan (twice) and Iraq once, spanning almost two months total – in combat zones!”

Wendell’s heartfelt approach also showed when asked how he would like to be remembered as a player. He said, “I was a player that gave 100 percent each and every time [I] stepped foot between the lines. I never went through the motions. I wanted to win for my team every time I pitched, and I was a team player. I was selfless when it came to the team. I never turned down the ball when asked to pitch.”57

Last revised January 26, 2014

Sources

Grateful acknowledgment to Turk Wendell for his input. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes from him are from his handwritten responses on a draft of this biography, received in the mail on January 15, 2014.

Internet resources

http://baseball-reference.com

http://retrosheet.org

http://rotoworld.com

http://comc.com

http://imdb.com

Books

Crescioni Benítez, José A., El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997).

Notes

1 “Charles D. Wendell,” funeral notice, Dery Funeral Home, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, November 2006 (http://funeralplan2.com/dery/archive?id=80761). Beatrice Wendell’s maiden name was Barnes.

2 Rick Cooper, “A different cat,” Spartanburg (South Carolina) Herald-Journal, August 5, 1991, D1, D3.

3 Thomas Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1999), 164.

4 Cooper, “A different cat.”

5 Filip Bondy, “Folks Needed Relief from Turk,” New York Daily News, March 9, 1999.

6 Matthew Vasey, M.D., “Interview with Turk Wendell,” New York Journal of Style and Medicine, January 25, 2009 (http://nyjsm.com/athlete/Turk_Wendell_Interview.cfm)

7 Cooper, “A different cat.”

8 “Turk Wendell Is Throwback to Fidrych,” Associated Press, March 29, 1992.

9 Matt White, a lefty who pitched seven games in the majors in 2003 and 2005, is the other big-league alumnus of Wahconah.

10 “New Haven 200: Wacky Turk Wendell was as real as it gets,” New Haven Register, July 5, 2012.

11 “New Haven 200: Wacky Turk Wendell was as real as it gets.”

12 “Steven ‘Turk’ Wendell ’89, Baseball, Inducted 1996,” Quinnipiac College Athletics Media website (http://athleticsmedia.quinnipiac.edu/athletics/Hall-of-Fame/Plaques/Wendell.pdf)

13 Cooper, “A different cat.”

14 Vasey, “Interview with Turk Wendell.”

15 Cooper, “A different cat.”

16 Cooper, “A different cat.”

17 Kevin Kernan, “Former Met loves ranch life, hates ’roids,” New York Post, May 8, 2010.

18 Bob Nightengale, “Get the net,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1992, 4.

19 Nightengale, “Get the net.”

20 “Turk Wendell Is Throwback to Fidrych.”

21 Mark Lukens, “Wendell makes a pitch for eccentrics in brave new world,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, August 25, 1991.

22 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 164. Drawn from a preseason feature on Wendell by Eric Edwards of the San Juan Star (unknown date, 1991)

23 “Turk Wendell Is Throwback to Fidrych.”

24 Bondy, “Folks Needed Relief from Turk.”

25 Cooper, “A different cat.”

26 Cooper, “A different cat.”

27 Tim Kurkjian, “A Method to His Madness,” Sports Illustrated, July 22, 1991.

28 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 164.

29 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 164.

30 Steve Buckley, “The Class of ’92,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1992, 16.

31 Dave Van Dyck, “Chicago Cubs,” The Sporting News, February 3, 1992, 29.

32 “New arms arrive for Cubs,” Associated Press, June 16, 1993.

33 Bob Nightengale, “Around the bases,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1995, 14.

34 Joe Goddard, “Riggleman Demanding Uniformity,” Chicago Sun-Times, July 16, 1995. This version had just a deer tooth flanked by wild turkey spurs.

35 Sean Kernan, “Cubs’ brass may be taming Turk,” Daytona Beach News-Journal, May 7, 1995, 5D.

36 Paul Sullivan, “Forget the Act,” Chicago Tribune, March 9, 1997.

37 Ronald Blum, “Wendell heads back to bullpen for Mets,” Associated Press, December 2, 2000.

38 “Quirky contract for Mets’ Wendell,” wire service reports, February 11, 1999.

39 Just the previous month, Octagon had acquired the baseball practice of Woolf Associates, the Boston-based sports agency that had represented Wendell. Jack Toffey and Gregg Clifton were his agents. Liz Mullen, “Octagon buys Woolf’s share of baseball,” Sports Business Daily, November 20, 2000.

40 Blum, “Wendell heads back to bullpen for Mets.”

41 That mark lasted until 2007, when Aaron Heilman made 81 appearances.

42 Tom Keegan, “Turk Beats Rockies on Icy Mound,” New York Post, January 30, 2000.

43 Joe Torre and Tom Verducci, The Yankee Years, New York 9New York: Anchor Books, 20090, 125-126, 140.

44 Roberto Gonzalez, “Turk to the Rescue,” Hartford Courant, October 19, 2000.

45 Torre and Verducci, The Yankee Years, 140.

46 Blum, “Wendell heads back to bullpen for Mets.”

47 “Angry Turk,” Associated Press, October 27, 2000.

48 “New York ships Wendell, Cook to Phillies for pair,” Associated Press, July 28, 2001.

49 Vasey, “Interview with Turk Wendell.”

50 Don Bostrom, “Thome uses legs, bat, leather to lead Phils,” The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), April 15, 2003.

51 Tyler Kepner, “Pitching Saves Mets from Themselves,” New York Times, July 29, 2000.

52 This was in the 11th inning at Shea Stadium on May 16, 2000. Unfortunately, Wendell had given up a homer to Colorado’s Bubba Carpenter earlier in the inning, and the Mets could not tie the game.

53 Kernan, “Former Met loves ranch life, hates ’roids.”

54 Kernan, “Former Met loves ranch life, hates ’roids.” Wendell said almost exactly the same things in his interview with Dr. Michael Vasey.

55 Kernan, “Former Met loves ranch life, hates ’roids.”

56 Nicole Sequino, “Major-league morale,” Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), December 4, 2006. Wendell was accompanied on his 2006 trip by former Twins outfielder Marty Cordova. When he went to Iraq to boost morale in 2007, Mike Remlinger and Adam Bernero were with him.

57 Vasey, “Interview with Turk Wendell.”

Full Name

Steven John Wendell

Born

May 19, 1967 at Pittsfield, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.