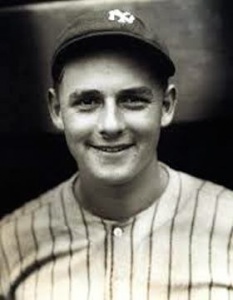

Waite Hoyt

Right-hander “Schoolboy” Waite Hoyt signed an option contract with the New York Giants as a 15-year-old in 1915. The following season he began a 23-year-career in Organized Baseball, including parts of 21 seasons in the big leagues, where he posted a 237-182 record and logged 3,762⅓ innings. Most remembered as a member of the New York Yankees in the Roaring Twenties, Hoyt averaged 18 wins and 253 innings per season over an eight-year stretch (1921-1928) as the Bronx Bombers won six pennants and three World Series titles for manager Miller Huggins. Dubbed the “Aristocrat of Baseball” by sportswriter Will Wedge, Hoyt excelled in the fall classic, holding the record for most appearances (12) and sharing the record for most wins (6) upon retiring. One of the first players-turned-broadcasters, Hoyt was the radio voice for the Cincinnati Reds for 24 years, from 1942 to 1965. In 1969 he was elected by the Veterans Committee to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Right-hander “Schoolboy” Waite Hoyt signed an option contract with the New York Giants as a 15-year-old in 1915. The following season he began a 23-year-career in Organized Baseball, including parts of 21 seasons in the big leagues, where he posted a 237-182 record and logged 3,762⅓ innings. Most remembered as a member of the New York Yankees in the Roaring Twenties, Hoyt averaged 18 wins and 253 innings per season over an eight-year stretch (1921-1928) as the Bronx Bombers won six pennants and three World Series titles for manager Miller Huggins. Dubbed the “Aristocrat of Baseball” by sportswriter Will Wedge, Hoyt excelled in the fall classic, holding the record for most appearances (12) and sharing the record for most wins (6) upon retiring. One of the first players-turned-broadcasters, Hoyt was the radio voice for the Cincinnati Reds for 24 years, from 1942 to 1965. In 1969 he was elected by the Veterans Committee to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Waite Charles Hoyt was born on September 9, 1899, in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. He was the first of two children (followed by Marguerite five years later) of Addison and Louise Josephine (Benedum) Hoyt. Of English and German stock, the Hoyts traced their ancestry to 17th-century Colonial America.1 Add, as Waite’s father was called, was a well-known minstrel and vaudevillian, and show-business manager. Waite’s introduction to baseball was on the streets of Flatbush and in alleys of theaters where groups of children hit rocks and balls with sticks and poles. By the time he began high school at Erasmus Hall, Waite had a reputation as a hard-throwing, precocious youngster whose poor grades prohibited him from playing on the school baseball team in 1914, but not from competing in local newspaper leagues as a member of the Wyandotts.2

Waite’s life took a dramatic turn in 1915. He got his grades in order, made the school nine, coached by Dick Allen, and soon developed into what the Brooklyn Eagle called the “sensation of the scholastic ranks.”3 Standing about 5-feet-10 and weighing approximately 165 pounds, the 15-year-old Waite overpowered the opposition, and attracted the attention of big-league scouts. He worked out with Grover Land, catcher of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the Federal League, and was offered a contract with its minor-league club, the New Haven White Wings of the Colonial League. The elder Hoyt, a former semipro third baseman who took immense interest in his son’s baseball proclivities, refused to co-sign the contract. By July, while still hurling for the Wynadotts, “Schoolboy,” as the local papers called Waite, began tossing batting practice for the National League’s Brooklyn Robins at the invitation of pitchers Nap Rucker and Jack Coombs. The following month, New York Giants catcher and scout Charles “Red” Dooin, whom the elder Hoyt had met, agreed to take a look at Waite during a Giants-Robins series at Ebbets Field in August. Dooin subsequently encouraged Giants skipper John McGraw to invite the teenager to the Polo Grounds to throw batting practice. Making the two-hour one-way trek to the Polo Grounds, Waite shadowed Christy Mathewson, in his last full season with Giants, and right-hander Jeff Tesreau. An impressed “Little Napoleon” wasted little time in securing Hoyt’s service. “I was the youngest boy ever to sign a (major-league) contract,” said Hoyt in an interview with historian Eugene Murdock, “and that brought a lot of publicity.”4 While making national news with his option contract, co-signed by his father, Waite led three different amateur and semipro teams to championships by the end of the summer. According to the Brooklyn Eagle, the teenager had a combined record of 34-2 and tossed four no-hitters for his various teams in 1915.5 Hoyt returned to Erasmus Hall in the fall, but his future was sealed. He never liked school, yet was articulate and well read, and supposedly excelled in English and journalism. After victories in his first three starts for Erasmus Hall in April 1916 (including two no-hitters four days apart), Hoyt left school.

Hoyt’s professional career commenced when the Giants sent him to Lebanon in the Penn State League in May 1916; however, his odyssey to the big leagues was anything but smooth as the next four years tested his commitment to the sport. Lauded as a “boy wonder” by Sporting Life, Hoyt won five games before the league disbanded;6 his only blemish was a 19-inning complete-game loss, 2-1.7 He subsequently played for Hartford and Lynn (both in the Class B Eastern League) in 1916, but spent two months sidelined by blood poisoning in his hands. Continuing his high-school education in the offseason, Hoyt was with the Giants during spring training in Marlin, Texas, in 1917. Described as “perhaps the most remarkable young athlete today,”8 Hoyt struggled, going a combined 10-26 with Memphis (Class A Southern Association) and Montreal (Double-A International League). Back in the Southern Association with Nashville in 1918 after participating in spring training with the world champion Giants, Hoyt was called to the big show in July. In his debut, on July 24, Hoyt tossed a 1-2-3 ninth, whiffing two in a 10-2 loss to St. Louis in the Polo Grounds. Soon thereafter, McGraw sent the 19-year-old to Newark in the IL.

If anything, Hoyt was stubborn, opinionated, and strong-willed, and butted heads with the equally obstinate McGraw. Disappointed by his demotion, he quit professional baseball and played for the Baltimore Dry Docks in a semipro league in late 1918. After spending the fall semester at Middlebury College in Vermont (even though he had not officially graduated from high school), Hoyt was traded to Rochester (International League) in January 1919; however, he refused to report and continued playing in Baltimore. “I didn’t want to go [to Rochester],” said Hoyt. “I never won in the minor leagues and I had had enough.”9 An exasperated McGraw finally traded Hoyt to New Orleans (Southern Association); and once again Hoyt refused to report.

Hoyt caught a break with the Dry Docks team in 1919. “Norman McNeal, our catcher, went to the Red Sox, and told their manager, Ed Barrow, about me,” recalled Hoyt. “When the Red Sox came to Washington, Barrow asked me, through McNeal, to come and pitch batting practice.”10 Ultimately, Barrow offered Hoyt a contract, but the 19-year-old had a stipulation. “I said I would sign if they put a clause in the contract that I’d start a game within four days after I arrived. I wasn’t going to sit around on any more benches or be farmed out. It was that or I’d quit.”11 Boston acquiesced, and purchased Hoyt from the Giants, yet encountered a stumbling block. Claiming ownership of the hurler, New Orleans filed a formal complaint with the National Commission, which ultimately rejected it.12

Hoyt’s debut on July 31, 1919, for the reigning World Series champions, who were mired in the second division, was the stuff of legends. “Schoolboy” hurled a 12-inning complete game to defeat Detroit, 2-1, at Fenway Park. “Cobb called me every name in the book,” recalled Hoyt, who won his next two decisions, including an 11-inning six-hitter against St. Louis. He lost six of his next seven decisions, interrupted by his first of 26 career shutouts, a three-hitter against the Yankees in their home park, the Polo Grounds, which they shared with the Giants. Hoyt recalled that pitchers were on their own and didn’t get help from veterans. “The only fellow who helped me was Herb Pennock, and that was a matter of personal friendship,” said Hoyt.13

Hoyt blanked New York on five hits in his first start of 1920 and won his first three decisions, but suffered a double hernia in early May while clowning around with teammates in the clubhouse. He underwent an operation and missed about 10 weeks. He pitched erratically upon his return in mid-July, finishing with a 6-6 record and 4.38 ERA in 121⅓ innings. Boston sportswriter James O’Leary noted that Hoyt was “hard to handle” and “had oceans of confidence,” but was not convinced that he would ever develop into a bona-fide big-league starter.14

Since the end of the 1918 season, Boston’s cash-strapped owner, Harry Frazee, had been systematically dismantling the club, trading pitcher Carl Mays in July 1919 and selling Babe Ruth five months later to the Yankees. On December 15, 1920, Hoyt joined those former teammates when he was sent along with starting catcher Wally Schang, pitcher Harry Harper, and infielder Mike McNally to the Yankees for second baseman Del Pratt, catcher Muddy Ruel, pitcher Hank Thormalen, and outfielder Sammy Vick. Hoyt claimed that he was not surprised by the trade which he consider fair. “I wasn’t proven yet,” he said.15

Hoyt’s playing career is defined by his decade with the Yankees. “The secret,” the quick-witted Hoyt once quipped about his success, “was to get a job with the Yankees and joyride along on their home runs.”16 Notwithstanding his consistency, Hoyt led the club in victories just once (in 1927) and was rarely considered the best pitcher on those Yankees staffs; that honor might have gone to hurlers like Mays, Bob Shawkey, Bullet Joe Bush, Sad Sam Jones, Herb Pennock (whom the Yankees acquired in 1923 from the Red Sox), or George Pipgras, each of whom enjoyed a season as good as, if not better than, Hoyt’s best season. Hoyt’s performances in the World Series established his reputation as, in the words of J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News, a “money pitcher.”17

Little was expected of Hoyt in his first year with the Yankees, who had finished in third place in 1920, just three games behind pennant-winning Cleveland. Hoyt earned manager Huggins’s trust in May by tossing four consecutive complete-game victories on the road, each on three days’ rest, to secure his spot as a dependable starter. Battling the Indians for most of the 1921 season, the Yankees won 30 of their final 41 games to capture their first pennant behind Ruth whose slugging captivated the nation and put fans in the seats. Hoyt finished with a 19-13 record, completed 21 of 32 starts among his 43 appearances, and logged a career-best 282⅓ innings with a 3.09 ERA.

The World Series featured the Giants and Yankees, and a clash of philosophies to be played out entirely in the Polo Grounds. McGraw refused to discard his Deadball Era tactics while Huggins embraced the new offensive, home-run-hitting style of his club. Though the Yankees lost five games to three in the third of three best-of-nine fall classics, Hoyt was lauded by the New York Times as the “individual star”18 and by The Sporting News as the “most sensational of all the hurlers” in the series.19 In Game Two, Hoyt tossed a sparkling two-hitter, striking out five and walking five. Hoyt “had at his disposal almost every variety of pitching known to the profession,” gushed the New York Times. “He exhibited to the startled Giants a complete line of fast shoots of varying height, but almost unvarying accuracy, as well as floaters of aggravating slowness, drops, and speedy and languid curves.”20 With the Series tied at two games apiece, Hoyt played “under terrific physical and mental pressure” and tossed a 10-hit complete game to win, 3-1 (the Giants’ run was unearned).21 Taking the mound in Game Eight on three days’ rest to battle Art Nehf for the third time, Hoyt completed his third straight game, yielding just six hits, but lost 1-0. The only run resulted on an error by shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh, who misplayed High Pockets Kelly’s grounder, allowing Dave Bancroft to score. Years after that game, Hoyt was still angry at home-plate umpire Ollie Chill. “He missed the third strike that cost me the final game of the 1921 World Series,” said the hurler.22 Had Chill called a third strike instead of ball four on Ross Youngs in the first inning, it would have been the third out and Kelly would not have batted. Hoyt did not allow an earned run in 27 innings and “stepped in Matty’s [Christy Mathewson] class,” opined the New York Times. (The Schoolboy’s one-time tutor tossed three consecutive shutouts in the 1905 World Series.)23

Widely expected to capture the AL pennant in 1922, the Yankees played the first five weeks of the season without Ruth, whom Commissioner Kenesaw Landis had suspended for breaking rules limiting offseason barnstorming. Hoyt kicked off the campaign by striking out a career-high 10 batters in his debut en route to three straight complete-game victories before losing to the Red Sox despite tossing a career-long 14-inning complete game. Led by a core of five pitchers who tossed 1,320 of 1,393⅔ innings and completed 100 of 152 starts [Bush (26-7), Shawkey (20-12), Hoyt (19-12), Jones (13-13), and Mays (13-14)], the Yankees won 41 of their final 59 games to overtake the surprising St. Louis Browns for the pennant. In a rematch with the Giants in the World Series, the Bronx Bombers were humiliated, losing four games to none. (Game Two was a tie.) After tossing a scoreless inning of relief in Game One, Hoyt was collared with the loss in Game Three, surrendering 11 hits and three runs (but only one earned) while Jack Scott, whom McGraw had snatched off waivers just two months earlier, pitched the game of his life, a four-hit shutout. In the offseason, Hoyt was a member of Herb Hunter’s All Stars, who toured the Far East in November. In the All-Stars’ only defeat, Hoyt lost to the Mita Club of Japan, surrendering nine runs and drawing the ire of Commissioner Landis, who claimed the Americans intentionally lost.

Hoyt was considered a “roisterer” and man-about-town during his playing days with the Yankees.24 In February 1922 Hoyt married Brooklyn native Dorothy Pyle, with whom he had two children, Harry and Doris. Married life hardly slowed Hoyt down. Standing about 6-feet and weighing 180 pounds, with dark hair and dark eyes, Hoyt also had a reputation as a lady’s man who enjoyed his drink and was “never lonely during the evening hours.”25 While Ruth’s epicurean tastes were the stuff of tabloids, Hoyt claimed that the Yankees’ reputation as carousers was overblown. “They were no better or worse than anybody else,” he said. “They played during Prohibition and the Roaring Twenties. They lived according to their times.”26 While a youthful Hoyt bounced back after an all-nighter, that would not be the case by the end of the decade.

Hoyt’s offseasons added texture to his captivating personality. Blessed with a pleasing baritone voice, he performed in vaudeville throughout the 1920s, sharing headlines with top acts such as Jimmy Durante. He also got involved in the mortuary and funeral business through his father-in-law. Sports reporter John Kieran aptly coined the moniker “The Merry Mortician.”

New York sportswriter Joe Vila suggested in 1923 that Hoyt “can be developed into the next Christy Mathewson,” but needed to “control his temper.”27 Hoyt was hot-headed, and was loath to take advice from Huggins or anyone else. While Yankee Stadium, the “House that Ruth Built,” opened to national fanfare, the 23-year-old hurler struggled, sporting just a 3-4 record and an ERA approaching 4.00 on June 26 as the Yankees gradually pulled away from all challengers. Vila claimed Hoyt suffered from “overconfidence” and “swollen pride.”28 But Hoyt turned his season around by going 13-4 from July 6 to September 26 with a 2.58 ERA to finish 17-9. Huggins once again relied on the big five pitchers [Jones (21-8), Bush (19-15), Shawkey (16-11), while newly acquired Pennock (19-6) replaced Mays], who logged 1,254 innings. Given the start in Game One of the third consecutive meeting between the Giants and Yankees in the World Series, Hoyt lasted only 2⅓ innings, yielding four hits and four runs in a 5-4 loss. He did not pitch again as the Yankees captured their first title, in six games, behind the pitching of Pennock and Ruth’s three homers.

After going 18-13 for the second-place Yankees in 1924, Hoyt dropped to a dismal 11-14 the following season as the Yankees fell to seventh place (69-85) in the wake of Ruth’s stomach illness that limited him to just 98 games. Described by Joe Vila as a “bust, like most of the other New York sharpshooters,” Hoyt was the subject of intensive trade rumors after the ’25 season.29

Just 26 years old, but in his 11th season of Organized Baseball in 1926, Hoyt had thus far failed to live up to the hype surrounding his initial signing by the Giants in 1915 and the greatness suggested by his performance in the 1921 World Series. The Yankees, with a healthy Ruth, and three infielders in their first full season as starters, Lou Gehrig, rookie Tony Lazzeri, and Mark Koenig, got off to a fast start, winning 30 of their first 39 games, and then survived a September swoon to stave off Cleveland and capture the AL pennant. While Pennock (23-11) and Urban Shocker (19-11) were seen as the aces of the staff, Hoyt rebounded to go 16-12 and log 217⅔ innings despite not making a start during a three-week stretch in July. According to Hoyt, he never suffered an arm injury on the mound, but was sidelined after he wrenched his elbow while throwing balls at a carnival.30

With the Yankees trailing the St. Louis Cardinals two games to one in the 1926 World Series, Hoyt “stagger[ed]” through nine innings, 14 hits and five runs (just two earned) as the Bronx Bombers, behind Ruth’s three round-trippers, bashed their way to a 10-5 win.31 Hoyt got the call in the deciding Game Seven at Yankee Stadium, and pitched “masterfully,” according to Richards Vidmer of the New York Times, but “luck was against him.”32 The Redbirds scored three unearned runs in the fourth inning on two errors. With the Yankees threatening in the bottom of the sixth, Hoyt was lifted for pinch-hitter Ben Paschal, whom Jesse “Pop” Haines retired. St. Louis held on to win, 3-2, behind 2⅓ innings of relief by 39-year-old Grover Cleveland Alexander. “It was heartbreaking for Waite Hoyt,” opined The Sporting News. “[He] had twirled brilliantly, even when his support sagged.”33

Hoyt has been described as appearing “almost casual on the mound, never creating the impression that he was bearing down with any great amount of sweat or strain.”34 Hoyt was a deceptively hard thrower, especially during his years with New York, even though he averaged only about three strikeouts per nine innings; he also had good control, walking 2.4 batters per nine innings in his career. “I was fast myself. As fast as [Tom] Seaver and I never struck anybody out,” said Hoyt. “I threw a palm ball, three-quarter speed ball, fastball and curveball, but it wasn’t too good, I must admit, and a slider at the end of my career.”35

“The Yankees were the best disciplined ballclub on the field that I have ever known,” Hoyt once said in an attempt to explain New York’s success in the 1920s.36 He considered the Yankees a family who bought into a philosophy of winning which manager Huggins embodied. “When we sat on the bench,” said Hoyt, “we weren’t allowed to talk about anything but baseball. When I got away from [New York], I realized why we beat those other clubs.”37

During spring training in 1927, Hoyt claimed to have had an epiphany while taking a solitary walk one evening. In what he described as a “personal inventory” of his actions and behavior on the field, he decided to rededicate himself to the sport and accept advice from Huggins and others.38 The result was his best season in one of the most storied campaigns in baseball history.

A seemingly relaxed Hoyt tossed a complete game to defeat the Philadelphia on Opening Day. While Murderers’ Row slugged its way through the opposition, enabling the Yankees to occupy first place for the entire season and finish in first place, 19 games in front of Philadelphia with a then major-league-record 110 victories (and only 44 defeats), Hoyt enjoyed the best season in his career. He won an AL-leading 22 games (lost just seven times) and set personal bests in complete games (23) and ERA (2.63), and also logged a team-high 256⅓ innings. At 27 years of age, Hoyt had emerged from the shadows of Mays, Pennock, et al. to become New York’s unequivocal ace. Hoyt developed an unflappable presence on the mound and finally learned to trust his teammates. He coined the phrase “Five O’Clock Lightning” to refer to New York’s explosive offense.39 An opposing team might be able to silence the Yankees for several innings, but by 5:00 P.M. (games typically started at 3:00) the Bronx Bombers, who led the AL in every major offensive category, would have their due. The overwhelmingly favored Yankees swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in a surprisingly competitive World Series. Hoyt pitched just well enough in the opening game (eight hits and four runs in 7⅓ innings), described by a New York correspondent as a “dull and unimpressive contest,” to squeak out the victory, 5-4.40

In 1928 the Yankees withstood a late-season challenge from Connie Mack’s Athletics to capture their sixth pennant in eight seasons by 2½ games. Hoyt finished with a career-high 23 victories (and just seven losses) and posted a 3.36 ERA in 273 innings, and was named the right-hander on The Sporting News All-Star team. Hoyt, and not 24-game winner George Pipgras, got the call in Game One of the World Series against St. Louis. Described as “unmistakably the hero” of the game by the New York Times, Hoyt tossed a three-hitter to win 4-1.41 Hoyt tossed another complete game in Game Four to complete the Yankees’ second straight sweep in the fall classic. Overshadowed by Ruth’s three home runs, Hoyt surrendered 11 hits and three runs (two earned) and drew praise from beat reporter James R. Harrison, who gushed, “[Hoyt] justified the claim that he is in the front rank of right-handed pitchers.”42

Hoyt slipped to 10-9 with an inflated 4.24 ERA in 201⅔ innings in ’29 as the Yankees’ dynasty was eclipsed by the A’s. After Hoyt got pummeled in a start on September 15, an exasperated Huggins, suffering from erysipelas, admonished the hurler to take better care of himself and sent him home for the rest of the campaign. It was the last time Hoyt ever saw Huggins, who checked into a hospital five days later and died on September 25. “Huggins was a father to me,” Hoyt often said. “[He] was the finest manager that ever lived.”43

A holdout in 1930, Hoyt clashed with new skipper and former teammate Bob Shawkey. With the Yankees struggling to remain at .500 in mid-May, Hoyt diagnosed the problem by claiming that “the trouble with the Yankees is that there are too many guys on it who are not Yankees.”44 Two weeks later Hoyt’s tenure with New York ended when he was traded along with Mark Koenig to the Detroit Tigers for Ownie Carroll, Harry Rice, and Yats Wuestling. “I think if Huggins had remained and didn’t die,” said Hoyt, “I wouldn’t have been traded from the Yankees. It hurt me was I was traded. It wasn’t the same with other teams. They were run more like corner lot teams.”45

After posting a 157-98 record with the Yankees, Hoyt bounced around with five different teams, Detroit, the Philadelphia A’s, the Brooklyn Dodgers (twice), the New York Giants, and the Pittsburgh Pirates, posting a pedestrian 70-72 record and logging 1,263⅔ innings working primarily as a part-time starter and reliever in the remaining nine years of his career (1930-1938). He battled his weight, ballooning to a reported 240 pounds, continued to abuse alcohol, and endured domestic problems resulting in his wife, Dorothy, filing for divorce in 1932. “I was fat and out of shape,” said Hoyt honestly. “I kind of loused up my career at this time.”46

Given his outright release by four teams in three years, Hoyt signed with Pittsburgh for the 1933 season and experienced a mini-rejuvenation, posting a stellar 2.92 ERA in 117 innings, starting eight of 36 appearances, though he won just five of 12 decisions for the runner-up Bucs. That same year, he married Ellen von Fliedner Burbank, from a wealthy Baltimore family; they had one child, Chris. Lauded by Pirates great and coach Honus Wagner as one of the smartest pitchers in the league, Hoyt relied on an array of breaking balls, such as a recently developed slider, and slowballs for his success. In 1934, the “old timer” won 15 games, completed eight of 17 starts among a career-high 48 appearances, and logged 190⅔ innings. Still capable of moments of brilliance, Hoyt tossed two of the best games in his career that season: his first and only one-hitter and the third of the three two-hitters; both were shutouts.

Hoyt ended his playing career where it began, in New York City, as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who purchased him from the Pirates in June 1937 and released him in May 1938. In parts of 21 seasons, he went 237-182, carved out a 3.59 ERA in 3,762 innings, and completed 226 of 425 starts among his 674 appearances. In seven World Series, including one with the A’s in 1931, Hoyt won six of 10 decisions and fashioned a stellar 1.83 ERA in 83⅔ innings.

With his background in vaudeville, Hoyt embarked on a career in radio in 1939. He hosted a pregame show for the Yankees, “According to Hoyt,” but had difficulty breaking in as a play-by-play announcer until the Cincinnati Reds hired him for the 1942 season. Over the next 24 years, Hoyt established himself as one of the most recognizable and most beloved broadcasters in America. He was a treasure trove of never-ending stories about the Yankees dynasty of the 1920s and Babe Ruth, whose reputation he defended. Hoyt argued that it was “a little bit stupid” to compare eras and players, and encouraged fans to learn more about baseball history.47 “The audiences would pray for rain,” said broadcaster Red Barber, “so that Hoyt could tell baseball stories. He had a priceless ability to tell a story interestingly and to tell it with dramatic emphasis and punch.”48 A sought-after dinner speaker, Hoyt also released two albums of his baseball stories.49

As an announcer Hoyt battled some of the same demons he did as a player. On June 21, 1945, he disappeared and was reported missing by his wife, who subsequently concocted a story that Hoyt was suffering from amnesia. It was later revealed that he had gone on a several-day drinking binge and had checked himself into a New York hospital for alcoholism. He returned to his job later that season and publicly apologized on the air for his drinking and actions. His honest admission made him even more popular with fans, who overwhelmingly supported him. For the remainder of his life, Hoyt was a vocal member of Alcoholics Anonymous. He often admitted that alcohol had robbed him of winning 300 games.50

Hoyt remained in Cincinnati after retiring as a broadcaster in 1964. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1969. Historians have since then questioned the credentials and Hall-worthiness of Hoyt, as well as others selected by the Veterans Committee at that time (such as Dave Bancroft, George Kelly, Jesse Haines, Chick Hafey, and Ross Youngs). One year after the death of Ellen in 1982, Hoyt married Betty Derie, who had worked in the offices of the National League from 1959 to 1970.51

At the age of 85, Hoyt died on August 24, 1984, from a heart attack. He is buried at Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted Waite Hoyt’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 According to many sources, Waite was once a member of the National Society, Sons of the American Revolution. His membership was revoked when he let his dues lapse.

2 As a youth Hoyt played in the Brooklyn Eagle League.

3 “Young Brooklyn Pitcher, After Many Tryouts, Seems to Have Struck His Big League Stride,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 10, 1919: 35.

4 Eugene Murdock, interview with baseball player Waite Hoyt, 1976. Cleveland Public Library (Hereafter Murdock interview).

5 “Junior Pitcher Goes To Giants,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 5, 1915: 2.

6 Sporting Life, July 28, 1916: 4.

7 “Waite Hoyt Loses 19-inning Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 19, 1916: 20.

8 Sporting Life April 14, 1917: 4.

9 Murdock interview.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 “Frazee Saves $1,500 on Pitcher Waite Hoyt,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 25, 1919:14.

13 Murdock interview.

14 The Sporting News, December 23, 1920: 1.

15 Murdock interview.

16 Tom Meany, “The Merry Mortician of the Mound,” Baseball Digest, March 1952: 89.

17 The Sporting News, April 2, 1942: 1, 4.

18 “Giants Win Series; Nehf Beats Hoyt, 1-0 in Thrilling Finish,” New York Times, October 14, 1921: 1.

19 The Sporting News, February 16, 1922: 7.

20 “Yanks Win 2d, 3-0; Hoyt Allows 2 Hits; Error Beats Giants,” New York Times, October 7, 1921: 7.

21 “Ruth Near Collapse After His Bunt Wins for Yankees, 3-1,” New York Times, October 11, 1921: 1.

22 Murdock interview.

23 “Giants Win Series; Nehf Beats Hoyt, 1-0 in Thrilling Finish,” New York Times, October 14, 1921: 1.

24 Meany: 90.

25 The Sporting News, September 20, 1934: 3.

26 Murdock interview.

27 The Sporting News. February 15, 1923: 1.

28 The Sporting News, June 28, 1923: 1.

29 The Sporting News, June 11, 1925: 1.

30 Murdock interview.

31 James R. Harrison, “Ruth Hits 3 Homers And Yanks Win, 10-5; Series Even Again,” New York Times, October 7, 1926: 1.

32 Richards Vidmer, “Valiant Alexander Turns Back Threat,” New York Times, October 11, 1926: 24.

33 The Sporting News, October 14, 1926: 5.

34 Meany: 92.

35 Murdock interview.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 James R. Harrison, “Ruth Blasts Road to Yankee Victory Over Pirates, 5-4,” New York Times, October 7, 1927: 1.

41 “Hoyt Is the Hero to Yankee Mates,” New York Times, October 5, 1928: 19.

42James R. Harrison, “Yankees Win Series, Taking Final, 7 to 3; Ruth Hits 3 Homers,” New York Times, October 10, 1928: 1.

43 Murdock interview.

44 William A. Cook, Waite Hoyt. A Biography of the Yankees’ Schoolboy Wonder (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004), 113.

45 Murdock interview.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 John Fay, “Hoyt Towered in Showers,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 26, 1984: B-19.

49 The albums were entitled The Best of Waite Hoyt in the Rain, volumes 1 and 2, released in 1963 and 1964. The latter volume is dedicated to stories about Babe Ruth.

50 Keith Kappes, “Fake sounds or not, ole Waite was the best,” Bdtonline.com, April 22, 2013.

51 Mike Dyer, “Waite Hoyt remembered as pitching, broadcasting great, doting husband,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 12, 2012.

Full Name

Waite Charles Hoyt

Born

September 9, 1899 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

August 25, 1984 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.