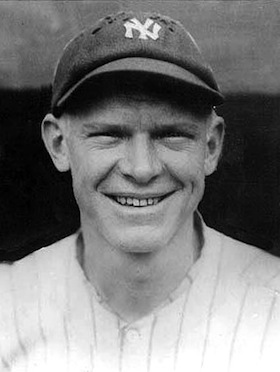

Whitey Witt

In a region noted for its rich baseball history, one of the Philadelphia area’s most precious treasures was surely a man named Whitey Witt, a big leaguer whose career began with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1916.

In a region noted for its rich baseball history, one of the Philadelphia area’s most precious treasures was surely a man named Whitey Witt, a big leaguer whose career began with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1916.

The quiet country street that bears his name provides the only conspicuous testimony to Witt’s his former presence there. He lived peacefully and without celebration deep in the farmlands of South Jersey. His was not a household name in baseball circles, but if you looked it up, you would find that Whitey Witt had an excellent career that was as fascinating as it was remarkable.

Regarded as one of the finest leadoff batters and fastest men of his era, the 5-foot-7-inch, 155-pound center fielder was an outstanding hitter and bunter, and the owner of one of the game’s best batting eyes. He was also an excellent fielder, one of the best of his era.

In ten years in the major leagues, Witt had a lifetime batting average of .287 with 1,195 hits in 1,139 games. Never a power hitter, Whitey hit a career total of 18 home runs with 302 RBI. He had 144 doubles, 62 triples, 489 walks, and 78 stolen bases. In a five-year stretch between 1920 and 1924, the left-handed-hitting Witt piled up successive batting averages of .321, .315, .297, .314, and .297.

The numbers, however, tell only part of the story. Witt, who played for the Athletics in the lean period between the club’s championship eras, was the first New York Yankee to bat in Yankee Stadium. He was one of Babe Ruth’s best friends, and was one of the few players who could hit the offerings of Walter Johnson.

In fact, Witt had a career built around Hall of Famers. He played for Connie Mack and Miller Huggins, roomed with Nap Lajoie and Zack Wheat, was there when Lou Gehrig broke in, and was good friends with Ty Cobb, Mickey Cochrane, and Goose Goslin.

When Witt talked about this group, he did so with relish, lacing his recollections with anecdotes that made it seem as though they just happened. Despite his years, when I interviewed him in 1984 the then-88-year-old codger was remarkably spry, as evidenced by his fondness for golf, a sport he played as often as three times a week with local friends and ex-players.

At that point, it was nearly 60 years since Whitey had pulled on a big-league uniform. But the charm and color of his era were still evident in his conversation. While playing with the A’s, Yankees, and Brooklyn Robins from 1916 until 1926, Witt appeared in what is often considered to be the golden era of sports.

Whitey was born on September 28, 1895, in Orange, a small town in central Massachusetts. His name was Ladislaw Waldemar Wittkowski. In his late teen years, he attended what was then called Goddard School, where he was not only noted for his baseball exploits, but was also a track star. Witt came to Philadelphia as a shy, 19-year-old shortstop with no minor-league experience.

“I went right from high school to the A’s,” he said proudly. “I was going to boarding school in Barre, Vermont, and playing in the White Mountain League. That was a summer league with teams sponsored by the big resort hotels in New Hampshire and Vermont. Most of the teams were made up of college boys from schools like Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth. They had summer jobs at the hotels.

“I was hitting over .400 while playing for St. Johnsbury,” Witt continued. “A scout was following me. One day I got a telegram from Connie Mack asking me to meet him in Boston.

“All I had on my mind was to play ball, so I went down to see him. When I got there, he said, ‘We’ve been following you. I’m going to give you a two-year contract, and you’ll get paid, whether you make it or not.’ He gave me a $500 bonus and I got a $1,800 salary. I came from a poor family with no money, and I was right out of high school, so I thought I had it made.”

Witt reported to the A’s the following season, and soon found himself the team’s regular shortstop. His second-base partner was Lajoie. “He was the most graceful infielder I ever saw,” Witt said. “His career was pretty much done by the time I got there, but he helped me an awful lot. He took me under his wing. None of the others helped me, but he sure did.

“Connie Mack had just broken up his club (which had won four pennants and three World Series since 1910),” Witt recalled. “After he won the pennant in 1914, he sold off all his great players. Then he stocked the club using a lot of college boys. We trained that year in Jacksonville, Florida. I’ll never forget it. Here I was, just a teenager, and I had made the grade.”

Witt also got a name change. “Mack didn’t want to write Wittkowski on the batting card every day, so he changed my name to Witt. Then, because I had blond hair, he called me Whitey.”

In his rookie season, Witt led the American League shortstops in errors with the unfathomable total of 78. The A’s finished last, a feat they duplicated every season from 1915 through 1921.

“We had some pretty good players back then,” Witt said. “Guys like Stuffy McInnis and Joe Dugan, my roommate later on. We had Rube Oldring in left, Wally Schang was the catcher, and we had Joe Bush pitching. But it was hard playing on those teams. You’re losing all the time. It was no fun. When I got to the Yankees, it was so much different. We were always up in the race, and it was easy to play ball.

“I wasn’t a very good shortstop,” Witt declared. “But I could hit, so Mack kept me in the lineup.”

Playing mostly at shortstop but occasionally at third base and in the outfield, Witt hit .245 his first year and .252 in his second season. Before he got to play his third year, though, he was drafted for World War I.

“When I came back (in 1919), Connie Mack put me in the outfield,” Witt said. “That’s where I played the rest of my career.”

Although he played briefly at second base in 1919, Witt wound up in left, then moved to right one year later. He lifted his average to .267 the first year back from the Army, then put together two strong seasons of .321 and .315. He had career highs in hits (198) and at-bats (629) in 1921.

During the winter of 1921-22, Witt petitioned Mack for a raise. “I had played five years for Connie Mack, and I hit awful good for him.” Witt recalled. “The last year, I played in all 154 games. By then, I was living right here where I do now (near Woodstown in South Jersey). I had bought the place in 1921 – Mack let me borrow $2,000 for the mortgage. I went up to his office five different times to ask for a raise, Finally, he said, ‘I’m either going to give you a $500 raise, or I’m going to keep you out of baseball.’

“Now, that was after I’d played all those years for him. That really got under my skin. I took the raise, but I wasn’t too happy.

“That spring, we trained in Eagle Pass, Texas. We played all our exhibition games against the St. Louis Cardinals because they trained in Texas, too. One day, I’m playing right field. It’s only a week before the season is to open, and it’s pouring rain. I’m standing in water up to my ankles, I’m soaked to the skin, and I’m mad as hell for not getting any more money. The winning run’s on base, and the ball comes to me. Instead of throwing to third, I just threw it over the catcher’s head into the grandstand. The run scored, and we lost the game. Afterward, Mack calls me over, and he says, ‘I’m going to get rid of you. Where would you like to go?’ I didn’t care.”

Mack sold Witt to the Yankees for a reported $15,000, a huge sum in those days. “I didn’t want to leave the A’s,” Whitey said. “I had hit good for them, and I had the farm in South Jersey. I had three or four thousand dollars in the bank. But it turned out pretty good, going from a tail-ender right into the World Series with Babe Ruth and that bunch.

“I didn’t report to the Yankees right away,” Witt added. “I got there three or four days after the season had opened. They said, “Where the hell have you been?’ I told them I had taken a little vacation. I had gone to Atlantic City.

“Miller Huggins was the manager. He was a nice guy. He had been a player, so he understood. He said, ‘Look, it’s going to cost you more to live in New York than it did in Philadelphia.’’ And he gave me a $1,500 raise, bringing my salary to $9,000. Right away, I started to hit like hell. The Yankees put me right into the lineup because that was the year that Commissioner Landis had suspended Ruth and Bob Meusel for playing in postseason exhibition games the year before. The Yankees needed outfielders.”

Witt was installed as the Yankees’ center fielder and leadoff batter. After Ruth and Meusel returned from their six-week suspension, Whitey became the anchorman, playing between the two lumbering sluggers. Later, he would say that racing back and forth between those two in every game wore him out and shortened his career.

“I had to cover a lot of ground between those two guys,” Witt said. “But I was fast. I could run the 100 in 10.2 seconds in high school, and I could do the 220 in 23 seconds. They were pretty good times for those days.”

Witt ended his first season with the Yankees with bandages on his head but a smile on his face. He had led the American League in walks with 89 while hitting .297 and scoring 98 runs.

“Right at the end of the season, we went into St. Louis for a three-game series with the Browns. We were both fighting for the pennant, so there was a big crowd, and they had the field roped off. In the first game, I was going after a fly ball and somebody threw a Coca-Cola bottle that hit me in the head. Knocked me out, and they had to carry me off the field bleeding on a stretcher. It was a really nasty crowd, and after I got hit, a riot almost broke out.

“I didn’t play the next game, which we lost, but I came back in the third game with my head all bandaged, and I got a hit in the eighth inning that won the game, 3-2, and the pennant.” (Witt’s eighth-inning hit actually made the score 2-1 St. Louis, and the Yankees won the game with two runs in the ninth, one driven in by Witt.)

After winning the pennant by one game, the Yankees lost in the World Series for the second straight year to the New York Giants, this time getting swept in a five-game Series (one was a tie). Witt hit just .222 for the Series.

The following year, though, the club’s luck changed. It all began in the season opener when on April 18, 1923, the gates were opened to a brand-new Yankee Stadium. Some 74,000 fans, well above the seating capacity of 58,000, jammed into the ballpark. Thousands of others stood outside in the surrounding streets. World-famous conductor John Philip Sousa and his Seventh Regiment Band were featured in the pregame festivities, and Governor Al Smith threw out the first ball.

The game started at 3:30 P.M. with shortstop Chick Fewster of the visiting Boston Red Sox grounding out. After New York pitcher Bob Shawkey went on to retire the side in order, it was the Yankees’ turn at the plate. The first Yankee hitter to bat in the new ballpark was leadoff man Witt. He sent a hard grounder to Fewster, who threw to George Burns at first for the out.”

Witt was not through making history. In the third inning, he was walked by Boston pitcher Howard Ehmke with two outs. After an RBI single by Dugan, Ruth stepped to the plate.

Before the game Ruth had told a writer, “I’d give a year of my life if I can hit a home run in the first game in this new park. Ruth got his wish when he ripped an Ehmke pitch into the stands in deep right field. Witt came home, thus becoming the first Yankee to score on a Ruth home run at the new ballpark. The Yankees went on to win the game, 4-1, with Whitey ending with a single and a walk in three official trips to the plate. Shawkey got the win with a three-hitter.

”It was an amazing day,” Witt recalled. “The new ballpark, the crowd, all the excitement. It was an experience that you could never repeat in a hundred years. We were in awe when we first saw the park. It seemed so big. Huge. At the time, there was nothing like it in baseball. Looking around, it was enough to make your eyes pop out.”

From there, with Whitey hitting .314, scoring 113 runs, and hitting a career-high six home runs, the Yankees went on to win the pennant and capture their first world championship. In the World Series, they beat the Giants in six games. Witt’s two doubles, a single, and a sacrifice fly accounted for two RBIs in the fourth game, won by the Yankees, 8-4. Whitey finished the Series with a .240 batting average.

“Each Yankee player got $3,132.50 for the winner’s share,” said Witt. “I’ll never forget that. They didn’t give rings to us, either. They gave us solid gold watches. It’s a great thrill to play in a World Series. But it was a bigger thrill for me to play with my dear, beloved Babe Ruth.”

Ruth was the same age as Witt. The two became inseparable friends on and off the field, and even roomed together for a while – or at least they stayed in separate rooms in the same suite, an experience about which Witt had countless stories. Teammates sometimes called Witt “Babe’s errand boy.” Ruth called Whitey “Laddie Boy.” “Get on your bike, Laddie Boy,” Ruth would yell when a ball was hit toward him in right field. Once Whitey and the Babe were even fined by Yankees owner Jake Ruppert after the two were found drinking heavily in an illegal brewery in Chicago during Prohibition. Ruth was fined $5,000 and Witt was hit with a $500 fine. When the Bambino died in 1948, Witt stood by his casket at the viewing at Yankee Stadium for five hours.

“Babe Ruth always considered me one of his best friends,” Witt said. “I loved the guy. There was a lot of jealously on our club. Some guys were always knocking Ruth, calling him a big bum and so forth. Wally Pipp was one of them. Once, they had a hell of a fight. I always said to those guys, ‘Why do you knock him? He’s our meal ticket.’ We would have been nowhere without him.

“Ruth hit the ball better than anybody. And he was a hell of a nice guy. He loved kids, he loved to visit hospitals, he loved the women. He always had a big bankroll with him. He never drank as much as people said he did. But he ate a lot. In my book. there were two great ballplayers in my day – Ruth and Ty Cobb. They were two of the greatest of all time. Ruth had color. Cobb was spectacular. Everything he did was spectacular.

“I’ll never forget, when I played shortstop for the A’s and Cobb would be on second. After every pitch, he’d run about halfway to third, and dare the catcher to throw the ball. If he threw it back to second, Cobb would be on third.

“Connie Mack always had pregame meetings. He would get up and say, ‘Today, we’re playing Ty Cobb.’ He would never say, ‘The Detroit Tigers.’ It was always, ‘Ty Cobb.’ He’d say, ‘Always throw the ball two bases ahead of Cobb.’

“One day, I’m playing left field and the ball comes out to me on one hop. Cobb leaves second, but he gives me the impression that he’s going to stop at third. He’s just going along nice and easy. I took the ball, and threw it to the plate. I caught Cobb by about 20 feet. He never even slid.”

In Witt’s last year with the Yankees, the club had a rookie first baseman named Lou Gehrig. Whitey had vivid memories of the young slugger. “To me,” Witt said in a moment of slight exaggeration, “Gehrig was more valuable to the ballclub than Ruth because he was very consistent. He seldom struck out, and he could drive in runs. He always had the bat on the ball.

“The most consistent hitter I ever saw, though, was Joe Jackson. He was the best pure hitter. And he was a real graceful player. He and Lajoie were both very graceful and both were great hitters.”

Witt said that the best pitcher he ever came up against was Hubert “Dutch” Leonard, the Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers left-hander. “I always figured he was going to hit me right in the ribs,” Whitey said. “He was a sarcastic guy, too. I never liked batting against him.

“Now, Walter Johnson, if you look back, you’ll find I hit very good against him. He had a speedball that would knock the bat right out of your hands. But I was a punch hitter. I could get the bat around on him. I bet I hit .400 against him. (Actually, Witt went 28-for-90 against the Big Train, a .311 batting average.) In fact, Connie Mack used to say, ‘Today, we’re playing Walter Johnson. I want you boys to watch how Whitey hits against him.’ Johnson didn’t have a good curve. It wouldn’t break much. But he had one of the greatest arms God ever put on a man. His speedball came up, and it looked like a golf ball coming at you. If he hit you, he’d have killed you.

“One time we were down in Washington, and both clubs – the Senators and Yankees – were leaving town at the same time. I went down to the railroad station, and I’m walking along the platform. Both clubs were in the dining car getting ready to eat dinner. A window was open, and who’s sitting there, but Johnson. He hollered out, ‘Hey, Whitey, Come here. I want to talk to you.’ So, I go in and have dinner with him.

“He says, ‘There are three guys in the American League that I cannot get out. Eddie Collins, Eddie Murphy, and you.’ I thought that was a great honor, coming from the best pitcher in the American League.”

“Some other pitchers were easy to hit, some were tough,” Witt continued. “But I always figured I could hit any of them. Hitting was my main asset. I could field and I could run. At first, I had a good arm, too, until something hit me in the shoulder. But usually in the big leagues, if you can hit, they want you in the lineup. And since I could hit, I was in the lineup every day.”

One pitcher whom Witt hit with spectacular results was Ehmke. In 1923 Ehmke pitched a no-hitter against the Athletics. In his next outing, he had another no-hitter going in the last innings against the Yankees. Witt ended Ehmke’s bid for a double no-hitter when he bounced a single off the third baseman’s chest. The ball then hit the Yankee third-base coach, and Witt beat it out for a hit.

Whitey, whose highest salary was $9,000 for one season, wrapped up his career with the Yankees after the 1925 season when he hit just .200 as a reserve outfielder after being replaced by a promising youngster named Earle Combs, who hit .342 in his first full season. That winter the Yanks sold Witt to the Brooklyn Robins, where he roomed with Zack Wheat. Witt said that Wheat was part native American. “Zack was good friends with Jim Thorpe,” he said. “The two of them could sure drink. Thorpe would come to the hotel room, and they would polish off a fifth of whiskey in one evening.”

Witt hit .259 in one year as a reserve outfielder in Brooklyn. After playing in his last game on August 18, 1926, and getting released at the end of the season, he dropped down to the minor leagues, a level at which he had never played before. Witt spent three years in the minors, playing one season each with the (San Francisco) Mission Reds, the Kansas City Blues, and the Reading (Pennsylvania) Keystones. At the end of the 1929 season he retired from professional baseball and returned for good to his home in South Jersey.

After his retirement from baseball and until 1971, Witt owned and operated a tavern called Whitey’s Irish Bar on Main Street in Woodstown, New Jersey. Ex-players and fans flocked to the bar nightly to hear the friendly and gracious Witt tell stories about his playing days. For a while he also managed and played for a semipro team in the area while palling around with his neighbor, former Washington and Detroit great and future Hall of Famer Leon “Goose” Goslin.

Eventually Witt, whose wife, Mary McClain, died in 1962 – the couple had no children – sold the bar. For many years thereafter, he spent his winters in Florida and his summers in South Jersey, where into his early 90s he played golf three times a week and drove himself twice a week to a race track across the bridge in Delaware. Whitey was also a regular participant in old timer’s games at Yankee Stadium, and was a featured guest at the ballpark’s 25th-anniversary celebration in 1948.

In his later years, while toasted by the local townspeople, Witt lived alone with his memories and mementos in the 160-year-old farmhouse that he had bought in 1921 and restored in later years. The house was eventually surrounded by farms that raised harness racing horses. Witt loved golf almost as much as he did baseball. “I can’t hit the ball far,” he said as he approached 90 years of age. “I only hit it about 150 yards off the tee. But I can chip and putt with anybody around.” And so he could. Sometimes, he even shot his age. Whitey, the only surviving member of the 1923 Yankees team, played golf the day before he died at home in 1988, just short of his 93d birthday

Sources

This biography is based on the chapter “A Rich Career Among the Greats” from the author’s book Diamond Greats – Profiles and Interviews with 65 of Baseball’s History Makers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988). Statistics were verified by baseball-almanac.com.

Full Name

Lawton Walter Witt

Born

September 28, 1895 at Orange, MA (USA)

Died

July 14, 1988 at Salem County, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.