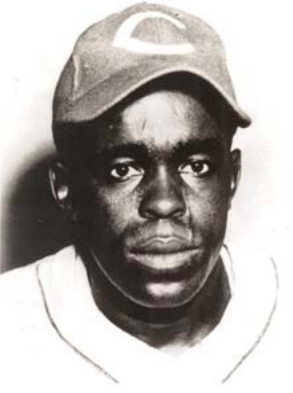

Cecil Kaiser

Cecil Kaiser earned the respect of his Negro League peers during a career that included seasons with the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, all-star appearances, a stint with a well-known barnstorming team, and one especially strong Winter League performance. The southpaw had two different nicknames that spoke of his prowess on the mound: “Minute Man,” a reference to the short length of time it took Kaiser to strike a batter out, and “Aspirin Tablet Man,” for his deceptive pitches that made the ball look like an aspirin pill.

Cecil Kaiser earned the respect of his Negro League peers during a career that included seasons with the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, all-star appearances, a stint with a well-known barnstorming team, and one especially strong Winter League performance. The southpaw had two different nicknames that spoke of his prowess on the mound: “Minute Man,” a reference to the short length of time it took Kaiser to strike a batter out, and “Aspirin Tablet Man,” for his deceptive pitches that made the ball look like an aspirin pill.

During Kaiser’s heyday, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was not quite a household name, but his stature grew in succeeding years. His longevity certainly played a role: He lived to the ripe age of 94 and, during those final decades of his life, he attained the status of “Living Legend,” enjoying visibility at various Negro League commemorative events. Tributes came not just from the few players still alive to share personal reflections, but also from students of the game who were eager to publicly appreciate the veterans of the Negro Leagues’ twilight era. When Kaiser died in 2011, many obituaries dubbed him “the oldest living Negro leaguer” at the moment of his passing, a claim that was not easy to corroborate but that nonetheless conveyed the significance of his place in baseball history.1

Kaiser enjoyed a career of remarkable breadth. His talent and passion for the game won him stints with more than two dozen teams in eight countries in North and Central America. Even after retiring from organized ball in 1952, he managed to keep returning to the mound, first by playing in industrial leagues and later for old-timer teams.2

Cecil Kaiser was born on June 27, 1916, in New York City.3 He was denied a relationship with his parents: His mother, a washwoman, died in childbirth, and he never knew his father.4 He was raised instead by his grandmother Cornelia and grandfather Henry “Bud” Kaiser, a railroad worker. At some point, Bud’s job required the family to resettle in Wythefield, Virginia, but before he left New York, Cecil received a serious dose of inspiration by watching Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig play baseball at Yankee Stadium.5

Kaiser, a left-handed hitter, was not a pitcher originally. During the early 1930s he first played in the outfield, getting chances to compete in various sandlot leagues. His first stop was Welch, West Virginia, playing for the Welch’s All-Stars, and for the next three years he remained in the state while playing on the Bishop Street Liners, the Gary Grays, and the Kimball West Sox.6 By 1938 Kaiser had graduated to a higher level of play, having moved to Pontiac, Michigan, where he landed a spot with the Pontiac Big Six, a world-champion softball team. That same year he started playing with the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Manager Candy Jim Taylor was beset by an injury-plagued rotation and figured he might as well give Kaiser a shot as a starting pitcher. Comfortable in the outfield, the young player took the ball with trepidation but then proceeded to throw a complete-game victory. That fateful game sealed his place on the mound for good.7

Though Kaiser had now been converted into a pitcher, that stellar start with the Crawfords curiously did not lead to a permanent spot in Pittsburgh’s starting rotation. From 1939 to 1945 he played on multiple Detroit-based teams, including the Detroit Stars and the Motor City Giants. During this time, he also married Margaret Bernice Cole. Little information is available about the marriage save for a 1940 census record revealing that the husband and wife lived with her family in Pontiac, Michigan. Their daughter, Beatrice Mae, was born in December 1940, and two years later their son, Robert Cecil, entered the world. Michigan records of a divorce between Kaiser and Cole indicate that the marriage lasted 10 years.

The year 1942 marked Kaiser’s first trip south to play winter-league ball in Latin America. It became an annual ritual for the pitcher. After that first season in Tampico, Mexico, he played four consecutive seasons in Cuba. Meanwhile, during this stretch, he compiled a few highlight performances for various teams in the United States. Although career summaries of Kaiser do not list him as ever having played for the Toledo Cubs, a July 1943 story in the Cincinnati Enquirer identified him as one of the team’s star players. By that point in the season he had “a no-hitter and several one- and two-hit performances” already under his belt.8 The following season he struck out 17 batters in his first start of the season for the Motor City Giants.9

That successful start and others set the stage for Kaiser’s first call-up to the Negro National League with the Homestead Grays, where he joined a squad that featured some of the league’s greats, including Sam Bankhead, Cool Papa Bell, and Josh Gibson, though he did not get to enjoy their company for long. By year’s end he was back with the Crawfords, which meant he missed the opportunity to play in that year’s Negro League World Series between the Grays and the Birmingham Black Barons. Nonetheless, his memories of his time with the Crawfords, and particularly of owner Gus Greenlee, were positive. “The best guy in major-league baseball was Gus Greenlee,” he recalled years later. “You didn’t have to want for nothing. If you needed something, call him, and he would be there.”10

By this point Kaiser, having reached the highest level available at the time to black ballplayers, began to “play the circle,” as he called it, finding work whenever and wherever he could. “As soon as the scene was over [in the summer], I’d play in South America,” he said. The Winter Leagues offered significant incentives, starting with compensation. While Kaiser made a pittance of $700 per month as a member of the Homestead Grays, he recalled making as much as $3,000 per week plus expenses in Latin America. Of course, the fact that the Latin American leagues were not segregated was another clear advantage to him and other Negro Leaguers. “It was better playing in the Latin countries. Wasn’t no segregation,” he remembered. “Over here, you could run into a lot of trouble.”11

In 1947 Kaiser returned to the Homestead Grays. One of his teammates was first baseman Luke Easter, on whom Kaiser must have made a strong impression, because he later would be selected for the barnstorming Luke Easter’s All Stars. In 1948 Kaiser started but did not finish the season with the Grays, instead moving to the Detroit Wolves. Once again he missed a chance to play in the World Series at season’s end, and this time grab a title to boot. It also meant missing the final World Series the Negro League ever held.

Although the season concluded with that particular disappointment, the following year Kaiser was rewarded for his perseverance. First, he scored an invitation to play for the South team in the 11th Annual North-South All-Star Game, held in New Orleans.12 There, a run-in with the law before the game nearly kept Kaiser from playing, as he revealed in an interview nearly 60 years later. En route to his hotel, a taxi driver had tried to overcharge him to the tune of $60. Kaiser flatly refused to pay the fee, only offering the cabbie a dollar before proceeding to his hotel.

Soon after, he was taken to jail, as the arresting officers were unsympathetic to his account of the cab ride. Kaiser used the phone call permitted him to reach out to Allen Page, the “promoter extraordinaire” behind the North-South game.13 “Mr. Page, I won’t be able to play tomorrow because I’m in jail,” the pitcher lamented. It was a strategic play on Kaiser’s part: He knew that Page had a vested interest in having all his players available and that he was a known commodity with significant pull. The policemen immediately sensed the trouble they could be in if they proceeded. “No, you don’t have to do that,” they told Kaiser, promptly ending the phone call. “Take this guy back uptown,” the commanding officer ordered.14

After the North-South game, Kaiser concluded his “all-star” year that fall by joining his Grays teammate, Luke Easter, and other Negro League elites for a barnstorming tour. Luke Easter’s All Stars played all over the country, with several games scheduled against Bob Feller’s All Stars, including one at Wrigley Field.15

For Kaiser the tour represented the chance for him and his teammates to prove they could hold their own against the white players. “Our best teams could play with anyone, anytime, anyplace, and you know what? The white players knew it. They respected us,” he said. He valued that respect during the tour, even as he and other black players suffered daily discrimination, including having to wait outside a restaurant that refused them entry while the white players dined inside. “The white guys didn’t like it,” Kaiser recalled. “They didn’t think it was fair, but the higher-ups said it had to be that way. We just lived with it. We knew up front what was happening.”16

When winter came, Kaiser was playing in Latin America once again. The 1949-50 season was the apex of the southpaw’s career. Signed with the Caguas/Guayama Criollos in Puerto Rico, he ended the season with an ERA of 1.68, the best among the league’s pitchers.17 He also compiled a 13-2 record, and it was with that 13th win that the Criollos clinched the pennant.18 In the final tie-breaking game of the Caribbean World Series, the Criollos lost to Carta Vieja from Panama.19

It was convenient that Kaiser was excelling in the Winter Leagues because back in the States the decline of the Negro Leagues spelled job insecurity. He was enrolled in a draft that was set up after the dismantling of the National Negro League, with the remaining teams given a shot at the players still eligible to play. The Indianapolis Clowns drew Kaiser’s name, but he declined their offer to play, instead deciding to return to the Winter Leagues.20 In 1951 he added Canada to the circuits he covered as a professional player by playing for the Farnham Pirates of the Quebec Provincial League. He rounded out the pitching rotation but also occasionally filled in as an outfielder, thus picking up where he had started his career. The following year he played in the much warmer environs of Tampa in the Florida International League. It was there that he officially ended his US professional career.21

After Kaiser moved back to Detroit, the Industrial League beckoned. Starting in 1953, he found work at the Ford Motor Company and a roster spot on its baseball team, the Ford All Stars. At the time this was a common career move for ex-Negro Leaguers, especially the older players, like Kaiser, who were still in demand. “If you were a ballplayer, all you had to do was carry a wrench in your back pocket, walk around the plant a few hours a day and play games a few times a week,” he remembered to the Detroit Free Press.22 He stayed with the Ford All Stars until 1961, which marked his longest tenure with any team dating back to his sandlot beginnings.

For the next two decades, Kaiser largely remained out of the public eye. He married again, to Barbara Jean Treasvant, on November 6, 1971, and they went on to have four children together.23 He eventually left Ford and found a position as a deliveryman and maintenance worker for the Goodwill Printing Company, in the Detroit suburb of Ferndale.24 The most loyal of workers, he would keep that same job until 2009, the year the company closed down.

Kaiser was nowhere close to hanging up his spikes for good, however. He continued to find playing opportunities, including games for charity. A photograph in a 1982 issue of the Detroit Free Press captured the pitcher during one such game, looking spry on the mound for a player in his mid-60s.25 He even was documented playing as late as 1990, the year he turned 74 and filled a spot on the Miller High Life Old-Timers’ team.

That same year, Michigan Governor James Blanchard presented Kaiser with a commendation, recognizing him as a Living Legend of Negro Baseball.26 It was the first of many honors bestowed on Kaiser. In 2003, MLB’s Detroit Tigers invited him to their first Negro League celebration weekend. It became an annual tradition, and Kaiser played a regular role in the festivities.

A few years later, Kaiser became one of 30 retired Negro League players drafted by Major League Baseball for honorary purposes. In the draft, which was the brainchild of Hall of Famer Dave Winfield, each team selected one player. Kaiser, as the hometown favorite of Detroit, went to the Tigers. A post-draft summary of the 30 selections dubbed Kaiser the “quintessential barnstormer.”27

Kaiser died on February 14, 2011. After suffering a fall in his home in Southfield, Michigan, he was taken to the hospital, where his heart stopped.

Less than a month before he passed, he had once again been the special guest at a Negro League event, likely the final one he attended. On the importance of Kaiser’s presence that day, Louis Manley, cofounder of the Michigan Chapter of Negro League Players, voiced a sentiment held by many fans: “[Kaiser] is living history. Just meeting him is part of keeping alive the legacy of what the Negro League accomplished.”28

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Rob Neyer, “Cecil Kaiser, Oldest Living Negro Leaguer, Dies,” SB Nation, February 15, 2011, sbnation.com/mlb/2011/2/15/1995313/cecil-kaiser-oldest-living-negro-leaguer-dies, accessed December 31, 2016. Neyer shared some skepticism about the claim because “there were a lot of guys who played in the Negro Leagues for just a moment, and have been largely forgotten. Not to mention the many different definitions of ‘Negro Leagues.’”

2 James A. Riley, “Cecil Kaiser,” The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 455.

3 It should be noted that according to a few sources, including the player himself, Kaiser was born in 1918. Most sources, however, including his obituary, suggest he was born in 1916. Cecil Kaiser, video interview by Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Inc., February 22, 2007; Associated Press, “Negro Leagues Hurler Cecil Kaiser Dies,” ESPN.com, February 14, 2011, espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=6121692, accessed December 31, 2016.4 Kaiser, NLBM interview, February 22, 2007.

5 Ibid.

6 “Players Register: I-L,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research website, cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Players%20Register/I-L%202016-08.pdf, p. 214, accessed December 31, 2016.7 Riley, 455.

8 “Toledo Club to Oppose Homestead, Cincinnati Enquirer, July 20, 1943: 14.

9 “Giants’ Star Faces Crawfords,” Detroit Free Press, May 21, 1944: 14.

10 Kaiser, NLBM interview, February 22, 2007.

11 Ibid. For the sake of complete accuracy, the following points should be noted in regard to the $3,000-per-week salary figure given by Kaiser: 1) In order to accurately quote the interview, Kaiser’s exact words have been included in the text of this article; 2) In spite of Kaiser’s assertion, the figure must have been $3,000 per month as no player earned $3,000 per week; it is highly probable that Kaiser simply misspoke when he said “week” rather than “month.”

12 “Players Register: I-L,” CNLBR website, 215.

13 Ryan Whirty, “Negro Leagues All-Stars Were a Big Hit in the Big Easy in 1939,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 30, 2009.

14 Kaiser, NLBM interview, February 22, 2007.

15 “Easter Team Plays Feller Squad Tonight,” Los Angeles Times, October 25, 1949: Part 4, 4.

16 Michelle Kaufman, “Negro Leaguers Found Respect on Rough Road,” Detroit Free Press, February 1, 1994: 6D.

17 Associated Press, “Negro Leagues Hurler Cecil Kaiser Dies.”

18 Lou Hernández, The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues, 1947–1961: Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Puerto Rico and Venezuela (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 244.

19 “1950 Caribbean Series,” Baseball-Reference.com, baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1950_Caribbean_Series, accessed November 30, 2016.

20 Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, s.v. “Cecil Kaiser,” coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/kaiser.html, accessed November 30, 2016.

21 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 99.

22 Kaufman, “Negro Leaguers Found Respect,”6D.

23 Cecil Kaiser Funeral Pamphlet, ancestry.com, accessed November 30, 2016.

24 Associated Press, “Negro Leagues Hurler Cecil Kaiser Dies.”

25 “That Old Time Delivery,” Detroit Free Press, August 29, 1982: 1E.

26 “Congrats,” Detroit Free Press, July 11, 1990: 4B.

27 Justice B. Hill, “Special Negro Leagues Draft,” MLB.com, May 30, 2008, m.mlb.com/news/article/2795840/, accessed December 31, 2016.

28 Susan Harrison Wolffis, “Negro League Player Cecil Kaiser Surrounded by Images from the Past,” Muskegon Chronicle, January 14, 2011.

Full Name

Cecil Green Kaiser

Born

June 27, 1916 at New York, NY (US)

Died

February 14, 2011 at Southfield, MI (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.