Bill Steele

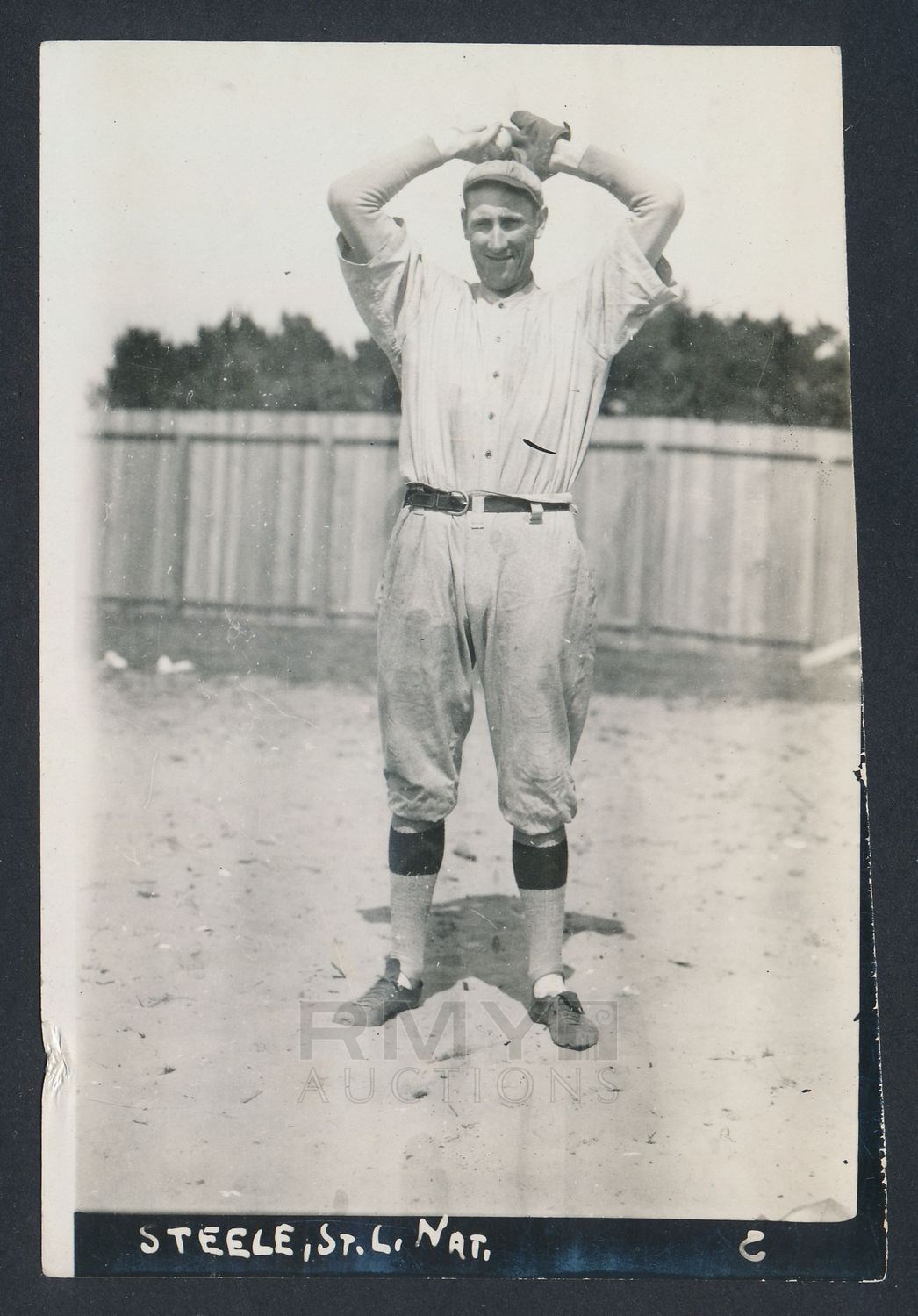

“His rise from the ‘bushes’ to the big show has been phenomenal,” gushed one report about Big Bill Steele.1 Two years removed from the sandlots, Steele jumped from a Class B league to the majors, debuting with the St. Louis Cardinals as a September call-up in 1910. That fall the spitballer won his first three starts en route to completing all eight of his starts, portending a bright future. The following season he won 18 games, but also tied for the NL lead with 19 defeats. Plagued by chronic hip arthritis, Steele was out of baseball after five seasons with a 37-43 record.

“His rise from the ‘bushes’ to the big show has been phenomenal,” gushed one report about Big Bill Steele.1 Two years removed from the sandlots, Steele jumped from a Class B league to the majors, debuting with the St. Louis Cardinals as a September call-up in 1910. That fall the spitballer won his first three starts en route to completing all eight of his starts, portending a bright future. The following season he won 18 games, but also tied for the NL lead with 19 defeats. Plagued by chronic hip arthritis, Steele was out of baseball after five seasons with a 37-43 record.

William Mitchell Steele was born on October 5, 1886, in Milford, a town of 800 residents in northeastern Pennsylvania. The seat of Pike County, Milford is situated on the upper Delaware River, which divides the Poconos in the Keystone State and Catskills of New York. His parents were the locally born Maurice Steele (1850-1909) and Caroline “Carrie” (Plaffel) Steele (1855-1925), born in New York City to immigrants from Germany.2 The two married in November 1873 and welcomed five children into the world, four of whom survived childbirth: Carolyn (1877-1951), Harry (1880-1946), William (1886-1949), and Emmett (1889-1953).3 The Steeles resided in a single-family house at 404 West Hartford Street, just outside of downtown Milford, which is now considered part of the New York City metropolitan area.

The elder Steele had a number of jobs, including working at Milford’s watch-case factory, a sawmill, and an ice business. He also occasionally served as a constable. The Steeles also owned a farm, where all six family members regularly toiled.4

Bill’s introduction to baseball was in the pastures and sandlots of rural Milford. By 1906 he starred as a hard-throwing right-hander and outfielder on Milford’s town baseball team. They traveled throughout the area, playing other semipro and local teams as far away as Trenton, New Jersey, as well as barnstorming Negro teams, such as the Cuban Giants. In June 1907 the Pike County Dispatch raved that 20-year-old Steele’s dazzling pitching was “more of a puzzle than ever with his shoots, drops and the ‘spit ball’ which he has thoroughly mastered.”5

Steele commenced his career in Organized Baseball in 1909 with the Altoona Mountaineers, in the eight-team Class B Tri-State League. Just as the season was starting, Steele was almost killed in a freak incident in a trolley car. According to a newspaper report, Steele “narrowly escaped being electrocuted” when he grasped a poorly insulated and highly charged sand lever on the platform and was “shocked almost to insensibility.”6 Despite that accident, which served as an omen to another one 40 years later, Steele pitched that day in relief. He won his first eight starts and proved to be a tireless workhorse.7 Among his 37 complete games in 39 starts were shutouts in both games of doubleheader against the Trenton Tigers in July, yielding just 10 total hits and knocking in the winning run in the 10th inning of the second game.8 In the 114-game season, Steele (19-21) finished sixth in victories, four fewer than the league leader, 19-year-old phenomenon Stan Coveleski; he also tied for the most losses in the circuit, and logged 359⅓ innings.9

Back with Altoona, which had changed its name to the Rams in 1910, Steele emerged as the Tri-State League’s best pitcher. By midsummer big-league scouts were tracking his successes. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, skipper Harry Ramsay “had been deluged with offers for his pet twirler,” including a special visit from a cohort from the Gateway City.10 Cardinals player-manager Roger Bresnahan, accompanied by club owner Stanley Robison, scouted the hurler and subsequently purchased him for $3,000 in early August.11 Steele went on to win a league-most 25 games (7 losses), while completing 29 of his 30 starts, and led the Rams to the title, prompting Philadelphia sportswriter Jim Nasium to opine that the “big ranky side-armer … looks like a finished product.”12

On September 10 Steele debuted at the Palace of the Fans in Cincinnati. Described by local sportswriter Jack Ryder as a “large and ferocious gentleman, with baleful ire in his amps and a curveball in his capacious mitt,” Steele overcame a rough first inning, in which he yielded five runs, to toss a complete game and win, 14-7.13 He also rapped three hits, including a triple, and knocked in the go-ahead run in the seventh. St. Louis sportswriters might be forgiven for initially misidentifying the recruit hurler for the Cardinals, who played 32 of their final 34 games on the road. Under the impression that he was former Boston Red Sox hurler Elmer Steele, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch praised his “excellent command” in beating the Boston Doves in his next start.14 With four victories in his first five starts and eight consecutive complete-game starts, Steele emerged as a bright spot in a forgettable season for the seventh-place Cardinals (63-90).

A moribund club that had recorded only two winning seasons since it joined the NL in 1892, the Cardinals seemed destined for another second-division finish for player-manager Bresnahan in 1911. Tragedy struck in late March when team owner Robison died, bequeathing the team and ballpark to his niece Helene Britton. The first female owner of a big-league team, Britton eventually transferred 10 percent of the team to Bresnahan, which led to rumors that she would sell the team to him or others.15

The Post-Dispatch opined, “[I]f Bresnahan’s team is to climb this year, it will be because the pitching is improved over the 1910 brand,” and mentioned Steele specifically.16 While the Cardinals lost 12 of their first 16 games, Steele was pounded in his first two appearances, then missed two weeks after getting hit in his right arm by a batted ball during batting practice.17 St. Louis sportswriters began referring to him as a tough-luck pitcher who suffered bad innings, late-game collapses, or from lack of run support. With a dismal 3-9 record, Steele seemed destined for yet another loss on June 11 when he yielded four first-inning tallies against the Philadelphia Phillies at Robison Field. But he settled down, went the distance, and won, 5-4, to give the Cardinals their 22nd win in their last 32 games and move them into fourth place. More importantly, he turned his season around, reeling off nine victories in 10 decisions over an exciting five-week period ending July 19. Teammate Miller Huggins, whom the Post-Dispatch called “the brains of the club on the field,” praised Steele for his “excellent work.”18

St. Louis was suddenly baseball-mad for the Cardinals, who were playing their best baseball since the halcyon days of the American Association of the 1880s when they were known as the Browns. The Post-Dispatch captured the euphoria, gushing, “This [team] is dazzling to a city which hadn’t had anything to speak of in the way of athletic leadership since the mid-Victoria period.”19 While sportswriter Ring Lardner praised the players for their “spirit” and “fine unassuming bearing on the field,”20 Sporting Life described Bresnahan as the “most popular” person in the city.21 The surprise team of baseball, dubbed the “Wreckers” by St. Louis papers, the Cardinals were engaged in a heated four-team pennant race in July, propelled by their “Big Three” pitchers: Bob Harmon, Slim Sallee, and Steele.

Steele’s rugged complete-game, 8-6 victory over the Boston Rustlers at the Hub’s South End Grounds on July 13 moved the Cardinals to within to a season-best two games of first place. They cooled down in the second half of the month, and gradually drifted toward .500, but finished in fifth place (75-74). Steele pitched inconsistently after his hot stretch, winning only two of his next nine decisions, one of which (a five-hitter on August 17 against the Phillies) proved to be the only shutout in his big-league career. He finished with 18 victories, completed 23 of 34 starts among his 43 games, and logged 287⅓ innings, all of which ranked second on the staff to Hickory Bob Harmon.22 Steele’s 19 losses tied the Phillies’ Earl Moore for the league’s most.

Considered a big player for the era, Steele was 5-feet-11 with blue eyes, black hair, and a long, elongated face marked by high cheekbones and a pronounced square jaw. He tipped the scales at about 200 pounds. According to the Post-Dispatch, he lost almost 30 pounds during the 1911 season acclimating himself to the scorching sun and humidity in the Gateway City. “[T]he hot weather during the middle of the season,” reported the paper, “sets him back a great deal and peels off too much flesh making him go stale and weakening him.”23

Steele was essentially a spitballer. One report gushed that he could “make the spitter break any old way he pleases. Some times it goes over with a slide shoot; other times it drops a foot.”24 He also occasionally tossed a fastball and slow ball.

With practically the same roster from the previous season, the Cardinals were expected to be a first-division club again in 1912. However, they lost 15 of their first 20 games, dooming the season by mid-May. Steele injured his arm in spring training in Jackson, Mississippi, and missed most of camp. Like his team, he struggled, and lacked the durability he showed the previous season. His record dropped to 3-7 and his ERA approached 6.00 by late June. After a disastrous 10-day banishment to the bullpen, Steele “rose heroic, like some grand old monolith by the River Nile,” quipped the St. Louis Star and Times sarcastically, tossing a seven-hitter and smashing a bases-loaded triple to beat the Reds in Cincinnati on June 29.25 Starting about once a week and relieving regularly, Steele commenced the best stretch in his career, going 6-1 with 1.95 ERA in 60 innings (June 29-August 3), helping the Cardinals to a winning month in July.

The Cardinals’ success in July briefly covered simmering tensions. Bresnahan clashed with Britton as it became clear that she would not sell the club to him. The demanding catcher also sparred with his hurlers, who were unable to repeat their success from the previous campaign. “The Cardinals failed dismally,” declared sportswriter Clarence F. Lloyd as the club lost 30 of its final 43 games to finish in sixth place (63-90).26

Just weeks after the season ended, Bresnahan was forced out as player-manager and replaced by Huggins. Huggins’s great difficulty was the “pitching department,” noted the Post-Dispatch.27 Save for Harmon and Sallee, the rest of the thin staff had regressed and finished last in team ERA in the NL in 1912. Steele’s case was especially troubling. He posted the highest ERA (4.69) and yielded the most hits per nine innings (11.4) among qualifiers in the majors. His two victories over the Browns in the October city series nonetheless pointed to his potential, continued the paper.

Steele dropped a bombshell in an interview with the Post-Dispatch in late February. He accused Bresnahan of not treating the players, and especially him, fairly. Furthermore, he admitted that he “laid down” and only tried to pitch well in a handful of games.28 The backlash against Steele was quick and fierce. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat jumped to Bresnahan’s defense, opining that he kept Steele “in the league when he was hardly deserving of the honor.”29 Furthermore, the paper suggested, “Steele is not deserving of the least bit of sympathy from anyone.”

Steele’s tenure with the Cardinals seemed to be over just as spring training in Columbus, Georgia, commenced. Considered a rabble-rouser by the Cardinals’ front office, Steele came down with a severe case of rheumatism in his right hip. He left camp in early March and returned home to Milford. It was widely believed that he would be released to the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association, but given the team’s lack of pitching, Huggins kept his hurler. However, he had no idea where the 26-year-old spitballer was.

According to the Globe-Democrat, Steele had no contact with the team after he left spring training until he mysteriously showed up a week into the season.30 He made his season debut on April 23 and “prolonged his big-league career,” opined the Post-Dispatch, by hurling a three-hitter to beat the Pirates, 3-1.31 Victory aside, Steele limped noticeably and had difficult running and covering first base. After failing to make it through three innings in three of his six starts in May, Steele was used sporadically. He was shelved for the season after his third consecutive disastrous relief outing, on July 9. According to one report, he had dislocated his right hip, though he probably still suffered from chronic rheumatoid arthritis.32 Steele (4-4, 5.00 ERA in 54 innings) was labeled a “complete failure.”33

Notwithstanding the brouhaha Steele caused, St. Louis papers genuinely believed that Huggins would turn things around in 1913. “Had anyone predicted a tail-end berth,” observed the Post-Dispatch, “a lunacy commission would probably have been appointed to look into the prophet’s head.”34 But the Cardinals were an atrocious team with what the newspaper called the “worst-looking assortment of twirlers imaginable.”35 The league’s lowest-scoring team with the highest team ERA, the Cardinals (51-99) finished in the cellar.

Steele was given permission to leave the team in July and return to home to Milford. In September he married Ann Farr Doyle, a local St. Louisan, though born in Ontario, Canada. They had met about 18 months earlier.

Back with the Cardinals at spring training in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1914, Steele boasted, “I feel as though I can win at least 25 games.”36 With a surfeit of starters, including Sallee and two youngsters, Pol Perritt and Bill Doak, who would emerge as stars, Steele was relegated to the bullpen, where he pitched primarily in low-leverage situations. As tensions grew between him and Huggins (whose staff ultimately led the NL with a 2.38 ERA and finished in third place), Steele was sold to the Brooklyn Robins on August 7. He made only eight appearances with the Robins, all but one in relief, and was optioned to Newark in the International League in the offseason.37

Given his unconditional release by Newark without having played a game with them, Steele signed as a free agent with Syracuse in the Class B New York State League. He lasted just over two weeks with the club before he was released in June for “failing to round into proper condition, thus ending his professional baseball career.”38 He resumed playing town ball and semipro ball in Milford and the region in 1915 and continued sporadically for the next few years.

In parts of five major-league seasons, Steele went 37-43, completed 40 of 79 starts among his 129 appearances, and posted a 4.02 ERA in 676⅔ innings. Lauded as one of the better hitting pitchers, he batted .203 on 47 hits.

After retiring from Organized Baseball, Steele lived Milford for several years before relocating to St. Louis with his wife. Their only child, Bernard, was born in 1919 in St. Louis. He eventually followed his father’s footsteps and was signed by the St. Louis Browns. In his first professional season, he batted .383 on 158 hits for the Pueblo (Colorado) Rollers in the Class D Western League in 1941. After serving in the military for four years, he returned as a 27-year-old in 1946, batting .299 in Class B and C ball before retiring.

Steele worked as a mechanic for the Swift meat packing company and later for the A&P grocery chain. He was described as a “modest and unassuming” man, who in his later years enjoyed raising New Zealand rabbits, which he supplied to St. Louis hospitals for medical experiments.39 His wife owned a confectionery store. She died in 1945.

Tragedy struck just weeks after Steele had made his first trip back to Milford in 24 years to visit with family, hunt down former teammates and friends, and celebrate his 63rd birthday. On the night of October 19, 1949, Steele was struck by a trolley car at the intersection of Midland Boulevard and Bristow Avenue in Overland, in northwest St. Louis, just two blocks from his home on 8275 Albin Street.40 He was removed from the rear wheels of the streetcar and taken by ambulance to St. Louis County Hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival. He was buried next to his wife in Memorial Park Cemetery in St. Louis.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Special thanks to SABR member Brian Morrison for his great assistance in determining Steele’s statistics for the 1909 and 1910 seasons with Altoona.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, newspapers via Newspaper.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 “Bill Steele Sold to St. Louis Team,” Altoona Times, August 4, 1910: 2.

2 “Death Claims Maurice Steele,” Pike County (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, January 31, 1924: 1.

3 “Obituary,” Pike County (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, November 12, 1925: 1.

4 “Death Claims Maurice Steele.”

5 “Base Ball News,” Pike County (Pennsylvania) Dispatch,” June 27, 1907: 1.

6 “Nearly Electrocuted,” Pike County (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, May 13, 1909: 1.

7 “Diamond Dust,” Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, May 29, 1909: 5

8 “Bill Steele Pitched Both,” Altoona Tribune, July 26, 1909: 3.

9 Statistics from “The Tri-State League 1909 Record,” 1910 Reach Guide (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach, 1910), 283.

10 Jim Nasium, “Hank Ramsay’s Collection of Long-Distance Clubbers Are Giving Altoona Big Lead for Tri-State Bunting,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 9, 1910: 10.

11 “Bill Steele Sold to St. Louis Team,” Altoona Times, August 4, 1910: 2.

12 Jim Nasium.

13 Jack Ryder, “Losing,” Cincinnati Enquirer,” September 11, 1910: 16.

14“Steele Scores Against Boston,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 16, 1910: 15.

15 Joan M. Thomas, “Helene Britton,” SABR BioProject. sabr.org/bioproj/person/helene-britton/.

16 “First Division is Not Too Far Away for Roger,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 8, 1911: 8.

17 “Steele Out for a Week,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1911: 12.

18 “Good Pitching and Confidence Boost Cardinals,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 13, 1911: 7.

19 “The Burning Question,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 20, 1911: 6.

20 Ring Lardner, Boston American, reprinted as “Police Escort Johnson from Boston Grounds,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 14, 1911: 7.

21 “The Cardinal Chief,” Sporting Life, July 1, 1911: 1.

22 Bob Harmon was a workhorse in 1911 for the Cardinals. The 23-year-old went 23-16, completed 28 of 41 starts among his NL-most 51 appearances, and logged 348 innings, which trailed only the Phillies’ Pete Alexander.

23 “Rogers Pitches Get Fast Work of 1912 Season,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Match 7, 1912: 17.

24 “Big Bill Steele Has Made Good,” Altoona Tribune, September 27, 1910: 10.

25 “Cardinals Best Red-Legs, 7-2,” St. Louis Star and Times, June 30, 1912: 17.

26 Clarence F. Lloyd, “Steele’s Double Victory Shocks Baseball Form,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 17, 1912: 21.

27 “Huggins Chosen to Manage Cards for 1913 Season,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 4, 1912: 14.

28 “Clarence F. Lloyd,” Ed Koney Going to Cards’ Camp at Own Expense,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 27, 1913: 17.

29 “Konetchy Leaves for Columbus This Evening to Begin Training Stint,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 27, 1913: 11.

30 “Cardinals and Konetchy Beat Pirates, 3-1,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 24, 1913: 10.

31 “Pitcher Steele Prolongs His Big League Life by Beating Pirates,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1913: 18.

32 “‘Bill’ Steele, Cardinals Pitcher, Weds in East,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 21, 1913: 24.

33 “Weak Battery Is Cardinal Alibi for 1913,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 2, 1913: 6.

34 “Weak Battery Is Cardinal Alibi for 1913.”

35 “Cards Have Won Three Games of 10 from Braves,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 10, 1913: 1.

36 “Big Bill Steele, Weighing 196, Is Ready to Twirl,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 16, 1914: 10.

37 “Steele and Enzmann Released to Newark,” Brooklyn Standard Union, January 12, 1915: 8.

38 “Diamond Briefs,” Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania), June 12, 1915: 18.

39 “Tragic Death of Big Bill Steele,” Pike County (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, October 27, 1949: 1.

40 Details about Steele’s death are from three separate obituaries: “Tragic Death of Big Bill Steele,” Pike County (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, October 27, 1949: 1; “Former Cardinal Pitcher Among 3 Traffic Fatalities,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 20, 1949: 20; and “Former Cardinal Pitcher Killed By Streetcar,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 20, 1949: 10.

Full Name

William Mitchell Steele

Born

October 5, 1886 at Milford, PA (USA)

Died

October 19, 1949 at Clayton, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.