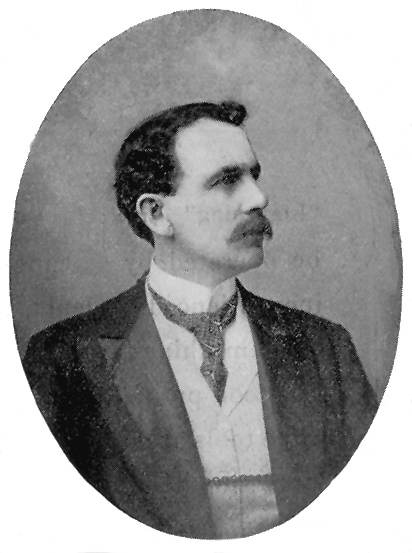

Reuben Stephenson

Reuben Stephenson was nicknamed “Dummy” by the fans and scribes because of his deafness. In baseball, friends, teammates, and opponents usually just called him “Steve” or “Stevey.” He grew up catching at the New Jersey School for the Deaf but landed with the Camden semi-pro club in 1892 as a center fielder, much to his dismay; he was quite vocal about his displeasure, still wanting to catch. Ironically, disgruntled as Stephenson was about manning center field, center field was his ticket to the big leagues. When Ed Delahanty went down to an injury in September, Phillies manager Harry Wright brought in the slugger from Camden.

Reuben Stephenson was nicknamed “Dummy” by the fans and scribes because of his deafness. In baseball, friends, teammates, and opponents usually just called him “Steve” or “Stevey.” He grew up catching at the New Jersey School for the Deaf but landed with the Camden semi-pro club in 1892 as a center fielder, much to his dismay; he was quite vocal about his displeasure, still wanting to catch. Ironically, disgruntled as Stephenson was about manning center field, center field was his ticket to the big leagues. When Ed Delahanty went down to an injury in September, Phillies manager Harry Wright brought in the slugger from Camden.

The job was only open for eight games, though. Delahanty soon returned, and there was little hope for a return call. No outfielder was going to crack that lineup. Philadelphia, with Delahanty, Sam Sam Thompson and Billy Hamilton, already had a Hall of Fame trio roaming the pasture. Stephenson bounced around from one minor league or semi-pro club for another decade and a half.

Reuben Crandol Stephenson was born on September 22, 1869, in Upper Township, a large town in Cape May County, New Jersey. During the first half of the nineteenth century the towns of Dennis and Ocean, now known as Ocean City, were separated from Upper because it was so vast. Stephenson is often cited as hailing from Petersburg, but that is merely a post office designation, not typically used as a biographical reference in baseball encyclopedias.

He was born to Leaming and Harriet L. (Crandol) Stephenson. Leaming, born in 1837, was from Upper; Harriet, from Dennis, was born in 1842. The couple met while working for the Thomas Van Gilder family in Upper during the late 1850s and early 1860s. Harriet was a household servant, and Leaming was a farmhand who supported his growing family as a miller. Leaming and Harriet had five children: Thomas, born circa 1864; Adaline, circa 1865; Charles, circa 1867; Martha, circa 1868; Reuben. Harriet passed away on May 17, 1871, when Reuben was but a year old.

Harriet’s sister Hannah, four years younger, moved in with the family to help raise the children. In 1873 she had Leaming’s son, also named Leaming, who died young. Leaming Sr. and Hannah were married on July 3, 1873. They had four more children: Aaron, 1874; Harriet, 1875; Rufus, 1878; Jesse, 1883.

Reuben was the only member of the family who was deaf, suggesting that the problem was not genetic. The deafness probably developed as a result of a childhood illness. The 1880 U.S. Census lists him as the only Stephenson child residing with his grandparents, the Crandols. The Census was taken during the summer, outside the school year. They may have taken him in because the Stephenson home was too cluttered with young children to give him the needed attention. Also, the Crandols were used to dealing with challenges, as one of their daughters in that Census is listed as “Idiotic.”

It is entirely likely that Stephenson attended and lived during the school year at a deaf school in a neighboring state until he was fourteen years old. New Jersey did not have such accommodations until September 1883, when the New Jersey School for the Deaf opened to student in Trenton. At that time, he enrolled at the new Trenton school. The campus consisted of the main school building plus dormitories, a chapel, a hospital and an industrial building used to teach and ply trades. Stephenson, now of high school age, resided at his new school as well from September through May.

Stephenson enjoyed his time at the Trenton school. He was particularly fond of his art teacher and of her instruction, particularly drawing and painting. He would later earn a living painting pottery and used his drawing skills to pursue mechanical jobs. The school newspaper, The Silent Worker, later bragged that after obtaining a mechanical job Stephenson was promoted within two weeks because of the advanced skills he learned at the institution. He also studied a trade, printing, but later admitted that the school’s equipment and instruction were too primitive for him to obtain employment as a printer. Stephenson often contributed articles for the school newspaper and even added a piece or two long after graduation, trying to motive others with hearing loss to aggressively seek employment and sharpen their motivation for life’s challenges. His future wife, Josephine Hattersley, a talented art student as well, was a classmate.

He also played baseball at the school. The Silent Worker started publishing in 1888 when Stephenson was eighteen years old. At that time, he was a member of the school’s top nine and probably had been for a year or two. The club, known as the Deaf-Mutes, played other school teams throughout the area and various amateur squads as well. A favorite playing field was the grounds owned by the black team the Cuban Giants. Stephenson officially graduated from the school in 1890 at age twenty but continued to play for the baseball team into 1892. He also played for the football squad even later than that.

The Silent Worker acknowledged in May 1888 that “Stephenson is undoubtedly the heaviest batter we have on our club.” In addition, “He enjoys the distinction of being the only one to knock the ball over the row of houses outside the right field fence of the school diamond,” particularly impressive because he was right-handed. He was a big guy, six feet and 180 pounds, and the nine’s starting catcher. It’s interesting that quite a few of the deaf professional ballplayers of the era were huge by comparison to the average athlete, including Stephenson, Luther Taylor, Ed Dundon, John Ryn, and George Kihm. Like Kihm, Stephenson also boxed and played football for extra cash. Most of the other deaf players mentioned came out of a much stronger baseball program at the Ohio Institute. Several other professional ballplayers came out of the Ohio school including William Hoy.

During the summers when school wasn’t in session, Stephenson played for various amateur and semi-pro clubs. The amateur teams included the Cape Mays, Libertys of New Jersey, Stars of Philadelphia, and Silentias of New York. Graduation in May 1890 freed Stephenson to commit to playing ball for money in the fall as well as the summer. He played for the Trenton semi-pro club during the summer, also traveling to New York on Sundays to play for the Silentias. He took a job that summer with the B.F. Walton brickyard in Trenton and played for the company team for $10 a game. Moreover, Stephenson played some games for the Stoll and Peter Fell team, a club sponsored by another Trenton brickyard. Over the winter, he was employed at the Morrisville (Pennsylvania) Rubber Works, where he would work off and on for over a decade.

When the baseball season began in 1891, Stephenson was found playing for the deaf school, the Trenton club again, and the Morrisville semi-pro club. He stuck with the Morrisville team, playing with them from June through October. In early September he worked out before a game between the major American Association clubs from St. Louis and Philadelphia in the latter city, catching Gus Weyhing. He impressed Charles Comiskey, George Wood and Weyhing; each commented favorably on the catcher’s future in the sport. In the fall Stephenson returned to the rubber mill but soon took a job at a woolen mill in Trenton because of the unhealthy nature of the environment at the rubber plant.

At the end of 1891, the Trenton Sunday Advertiser had a nice write-up: “Stephenson stands six feet in his stockings, weighs 170 pounds when trained down fine, is as straight as a dart and shows in his motions an agility rarely found in a man of his formidable proportions. His favorite position is behind the bat, although he plays first or second base with brilliant success. As a catcher he has shown great endurance and the ability to hold the swiftest and most erratic pitching, while his throwing is like a shot from a rifle cannon…With his strength and agility, he is of course a heavy hitter, as shown by the number of home runs and three-base hits which he has placed to his credit…Although profoundly deaf, Stephenson speaks very distinctly, and has learned to understand what is said to him by watching the speaker’s lips…His genial manners and good-heartedness make him popular even with those who think him a little too straight-laced in his rigid anti-beer, anti-tobacco and anti-cuss-word notions.”

Stephenson had his breakout year in 1892. In April he was catching for the Morrisville club and the Trentons, even performing against the New York Giants on the 13th with the latter nine: “Stephenson’s nimble antics [were] a rare treat for the Giants.” He also played for his old school in May and June. He soon joined the tougher Camden club. In 84 games he punched 39 home runs and batted .380. He initially had a little trouble with some teammates because he continually expressed his displeasure with playing the outfield; he wanted to catch. His manager disliked him for another reason. Despite leading the club in slugging, Stephenson was released during the summer for his supposed inability to hit. It was later learned that his manager was irate with him because Stephenson, a nondrinker, refused to attend gatherings at a local watering hole after each game. The manager had a financial stake in the saloon. A local newspaper noted, “If the Camden Base Ball Club ever made a mistake in their lives, they made a big one when they released the crack all-round player Stephenson. Few players in such short time made more friends than this popular mute, and many people went to the grounds more to see him play than anything else.” An upheaval by the fans quickly had Stephenson back in the lineup.

Stephenson’s 39 home runs were 25 more than any other member of the club. He was supposed to have received a gold watch from club president Samuel Easton as the leading slugger on the team. Easton reneged, though, ridiculously claiming that Stephenson needed forty to claim the prize. In September, Ed Delahanty of the nearby National League Philadelphia Phillies was felled by an injury. Manager Harry Wright had heard of the Camden centerfielder who was crushing the ball and brought him in for a week, eight games, until Delahanty was fit to return to the lineup. On the 9th he made his debut, as the North American noted, “The Phillies had a patched-up team in the field, Stephenson of the Camden club being in center, Charlie Reilly at third and Lave Cross at second.” In eight games between September 9 and 16, he placed ten hits in 37 at-bats for a .270 average. Delahanty returned to the field on the 17th, and Stephenson was released. In the late fall he played football for the semi-pro Volunteer Athletic Club of Morrisville as a kicker.

In January 1893 Stephenson signed with the Trenton club again, for $90 a month with the promise of an increase to $125 by the middle of the summer. He didn’t join the club, though, finding a slot in professional ball with Harrisburg of the Pennsylvania State League. He played with the club at least through July and then joined Reading of the same league. In 85 games in the league, Stephenson batted .331 with forty extra-base hits, including 15 triples. He also appeared on the mound for four shutout innings for Harrisburg in one game without a record. In July his grandfather passed away and left him “a large tract of land.” Over the winter, Stephenson worked at a Trenton watch factory.

In January 1894 a rumor hit the Trenton newspapers that Stephenson had died while on the operating table during ear surgery. It proved false. In March and April he coached the baseball team at the National Deaf-Mute College in Washington, D.C., now known as Gallaudet University. He played the entire season in the Pennsylvania State Association for five different teams: Reading, May 2 to July 11; Philadelphia, July 12 to August 22; Harrisburg, August 27 to September 13. He also played for the Allentown club managed by King Kelly in early July, but it’s not clear if they were league games. In mid-September he joined the Ashland club, the relocated Easton club which previously took Allentown’s place. These were probably non-league games as well. With Ashland, he collided with an opposing catcher and injured his left leg, finishing his season. In 81 games he hit .309. Stephenson spent the winter in Philadelphia driving a bakery wagon.

In early 1895 Stephenson joined Pawtucket of the New England League. In one game with Pawtucket he went 7-for-7, but Harry Davis was the club’s big stick. By the end of May Stephenson was with Fall River of the same league, appearing in a total of 19 games for both clubs. He hit a solid .367 in 90 at-bats and even posted a 2-0 record in three games on the mound. Stephenson returned home to Trenton to work as a pottery decorator. In 1896 he led the Virginia League with sixteen home runs, tying two others. He did so with three clubs: Norfolk, April 16 to June 18; Portsmouth, July 1 to 10; Petersburg, July 13 to August 1; Portsmouth, August 3 to September 17. In a total of 82 games, Stephenson hit .342

Stephenson landed with Newport in the New England League in 1897. He was beaned on the side of the head, ending his season. At the time he was batting .325 in 47 games. While at home he was involved in a serious bicycle accident which nearly killed him. In September he played for the Morrisville and Trenton YMCA semi-pro clubs. In November he played football for his old school. The winter found him working for a pottery firm in Trenton.

In 1898 Stephenson joined Auburn in the New York State League, playing with the club from May through July 31. Auburn “released pitcher Tommy Gallagher and first baseman Stephenson because of dissention between the two.” A week later, Stephenson caught on with Palmyra of the same league, playing with the club from August 6 to 15. He batted .279 in 71 games. In September he was at home playing for the Trenton YMCA.

On October 26, 1898, Stephenson, 29, married former classmate Josephine Hattersley, a 22-year-old Trenton native, at a Protestant church in Philadelphia. Per The Silent Worker, “Miss Hattersley has been noted for her beauty and remarkable grace of her gestures. Her sign recitations of poems and hymns have always been a treat to any company before which she has obligingly consented to render them. She is of medium height with a graceful figure, a lovely blond complexion and hair of that rare and most beautiful tint, ‘Titian’ bronze, and the rather unusual combination of deep brown eyes.” The same paper added some kind words for the groom as well: “Although his occupation has brought him into contact with a rough class of men, he has kept clear of all bad habits and is gentlemanly at all times in his manners and speech.” The couple had three children, all girls: Josephine Shaw, 1899; Marjorie Backes, 1910; Dorothy, 1915. None of the girls had trouble with their hearing.

The couple relocated to Philadelphia after the wedding, where Reuben found employment with a gas company. He vowed to give up baseball “as it is not, in his opinion, a good profession for a steady, married man.” He kept his promise by no longer traveling far from home to play. In fact, he may not have played at all in 189l. He did, however, box. “Dummy” Stephenson of Philadelphia defeated Soldier Wilson in the second round, foul out, on July 1. The Stephensons spent much of the year awaiting the arrival of their first child. He returned to the diamond in 1900, playing professionally for Philadelphia of the Atlantic League for two games between May 7 and 9. He continued to play regularly through 1906 but for semi-pro squads. In the early spring he coached ball at the New Jersey School for the Deaf. Both before and after the Atlantic League contests, Stephenson played third base for the Trenton YMCA club through October. In September he was named manager of the club. He also worked for a piano manufacturer, returning with his wife to Trenton, where they settled.

In May 1901 Stephenson played for the YMCA and even umpired a few games. One opponent was the Cuban X-Giants, an all-black club. According to the Trenton Times, “…We can truthfully say he is one of the most popular players who ever played ball in Trenton…He is at all times a gentlemen, both off and on the field. He does not belong to the class of players who so often bring our national game into disrepute by some disgraceful act.” From June through the end of the season, he played for Morrisville. In 1902, he tried to return to Organized Baseball with Jersey City of the Eastern League. Stephenson was listed on the club’s preseason roster but was dropped before the season without a tryout. He played with Morrisville from May to September and then joined Lambertville by the middle of the latter month. In 1903 he began the year with the YMCA, played with the Roebling, a wire rope company, team from mid-May through August and joined Lambertville in September. That year, he was employed at the rubber mill and a pottery company. In 1904 Stephenson played for a company team, Monument Pottery.

Stephenson played for the All-Trentons in April 1905 before joining the American Bridge Company team in May. He played regularly with the Bridgebuilders into 1906, finally hanging up his spikes at age 36. He worked as a potter for several years at least through 1911. Throughout the years Stephenson had championed the cause of the deaf. He was involved with the New Jersey State Association for the Deaf for years, even unsuccessfully seeking employment at the local state house. During the second half of the 1910s, he served two terms as the association’s president. In 1911, The Silent Worker exclaimed that Stephenson “is probably the biggest deaf man in the state,” referring to his exposure as both a ballplayer and advocate.

During the First World War, Stephenson found employment with the Burlington Shipbuilding Company, keeping the job until 1920. He then joined an automobile factory in Trenton. Subsequently, he was employed with the state highway department until the fall of 1925. By then, he was very ill and was hospitalized. He had diabetes for years and developed tuberculosis. Reuben Stephenson passed away at a Trenton hospital on December 1, 1925, at age 56. At the time, the once robust man was said to weigh barely 100 pounds. He was interred at the South Dennis Cemetery.

Note

The Silent Worker was much more than a school newspaper. It contained community information and other items of interest to the deaf community at large. The paper made it very easy to follow Stephenson’s career and life, as he was a leading member of the New Jersey deaf community, a celebrity.

Sources

Minor league statistics provided by Ray Nemec

Ancestry.com

Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Maine, 1895,1899

Baseball-reference.com

Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, Pennsylvania, 1891-92

Camden Post, New Jersey, 1892

Familysearch.com

News and Observer, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1896

North American, Philadelphia, 1892, 1894

Saturday Evening Press, Camden, New Jersey, 1892

The Silent Worker, Trenton, New Jersey, 1888-1924

Sporting Life, 1896, 1898, 1902

Trenton Sunday Advertiser, New Jersey, 1891

Trenton Times, New Jersey, 1892-1924

Photo credit

Robert F. Strohmeier

Full Name

Reuben Crandol Stephenson

Born

September 22, 1869 at Petersburg, NJ (USA)

Died

December 1, 1924 at Trenton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.