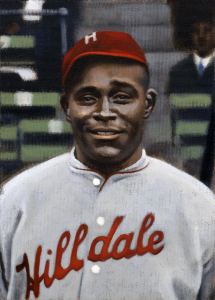

George Carr

“It is very doubtful if colored baseball has known a more dangerous hitter than George Carr,” wrote Cum Posey in 1937.1 Posey certainly knew a dangerous hitter when he saw one since, as the longtime owner of the Homestead Grays, he had employed Negro League legends Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard. Given the nickname “Tank” because of his stocky 5-foot-11, 200-pound frame, the switch-hitting Carr, a natural right-hander,2 added speed to his powerful build, consistently ranking among the league leaders in stolen bases. A versatile player, he made most of his appearances at first base, but by the end of his career had taken the field at every position but pitcher. Carr’s exploits on the East and West Coasts gained him admirers and acclaim as well as recognition from the influential Pittsburgh Courier, which included him on its all-time team of Negro League players in 1952.3 Although he never reached Cooperstown despite a career .311 batting average, he was a vital cog on some of the greatest baseball teams of all time.

“It is very doubtful if colored baseball has known a more dangerous hitter than George Carr,” wrote Cum Posey in 1937.1 Posey certainly knew a dangerous hitter when he saw one since, as the longtime owner of the Homestead Grays, he had employed Negro League legends Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard. Given the nickname “Tank” because of his stocky 5-foot-11, 200-pound frame, the switch-hitting Carr, a natural right-hander,2 added speed to his powerful build, consistently ranking among the league leaders in stolen bases. A versatile player, he made most of his appearances at first base, but by the end of his career had taken the field at every position but pitcher. Carr’s exploits on the East and West Coasts gained him admirers and acclaim as well as recognition from the influential Pittsburgh Courier, which included him on its all-time team of Negro League players in 1952.3 Although he never reached Cooperstown despite a career .311 batting average, he was a vital cog on some of the greatest baseball teams of all time.

George Henry Carr was born on September 2, 1893 (or possibly 1894 or 1895) in Atlanta, the son of Stephen and Idella Carr,4 Per the 1910 US Census, Stephen was a janitor and Idella was a dressmaker. The mystery regarding George’s birth year lies in the facts that his headstone states he was born in 1893, while Carr reported his birth year as 1894 in his World War I draft card and 1895 in his World War II draft card. Carr made his way to California at an early age, and attended Pasadena High School.5 However, according to census records, he attended high school for only about a year. On his World War I draft card, he listed himself as a “movie actor” at Universal City, California.6

Carr’s earliest documented baseball experience was in the winter of 1915-1916, when he played for a semipro team, the Los Angeles White Sox, in the winter months. The team occasionally participated in the California Winter League, which allowed African American baseball players the opportunity to compete against White major leaguers. He was recognized for his skill, with the California Eagle describing him as “what we might call an all-star player” and adding, “Carr hits like Tris Speaker, fields like ‘Stuffy’ McInnis, and despite the fact that he tips the beam around the 200-mark, he runs bases like Ty Cobb. Again we say, he’s some player.”7 With the exception of 1918-1919, when they did not play, the White Sox continued to exist as a semipro team over the winters, until they joined the California Winter League as a full professional team in 1920-21. Carr was the team’s manager in 1919-20.

Carr traveled east in the spring of 1920 to suit up for the Kansas City Monarchs of Rube Foster’s newly formed Negro National League. The Monarchs’ first NNL game took place on May 29, 1920. According to the Kansas City Sun, Carr was slated to “probably” start the contest in right field.8 In the next game, on the 31st, his versatility was on display: The Sun reported that “Carr, the Monarchs second baseman, made one of those impossible catches in the sixth inning to the electrification of all fans.”9

For that initial NNL season, Carr served as the Monarchs’ primary first baseman, and he turned in a fine .315/.355/.435 effort with a 132 OPS+, and finished fifth in the circuit with 18 stolen bases. In 1921 he played even better, slashing at .323/.389/.518, improving his OPS+ to 158, and ranking among the league leaders in home runs, RBIs, walks, stolen bases, and OPS. The Monarchs finished in second place behind Foster’s Chicago American Giants in both seasons.

After the 1921 season, Carr took his hot bat back home, batting .336 for the “Colored All Stars” of the California Winter League, a team that also included future Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston, Biz Mackey, and José Méndez

The 1922 NNL season brought a change of position for Carr; he moved off first base to roam the outfield, primarily center field. He struggled at the plate, perhaps due to the greater physical demands of playing the outfield, slumping to .265/.342/.378. His cold bat followed him to California in the winter as he struggled to a .214 average.

The 1923 season brought a newcomer to the Black baseball scene – the Eastern Colored League. As Foster had done with Midwestern teams, Ed Bolden led the organization of the ECL, which served to bring organized Black baseball to the East Coast and provided a new competitor to the NNL. ECL teams raided NNL teams for star players like Mackey, George Scales, Heavy Johnson, Pop Lloyd, and Charleston.10 Carr joined Bolden’s Hilldale Club, located in Darby, Pennsylvania (in the Philadelphia area), which became one of the great Negro League teams of the 1920s. The “Darby Daisies” took the first three ECL flags and, after losing the inaugural Negro League World Series to the Kansas City Monarchs in 1924, defeated them in 1925 to win the title as champions of all of Black baseball. Carr was back at first base, and was solid in the 1923 and 1924 seasons, posting 109 and 114 OPS+. In 1924 he batted .295 as Hilldale came up short in the first Negro League World Series.

After the 1924 season, Carr again went to California and had perhaps his best winter season, batting .383 with 11 home runs in 32 games.

Carr’s torrid play carried over to the 1925 ECL season. He was arguably the best first baseman in the league, ranking in the top five in slugging percentage, OPS, and offensive WAR while leading the league with 24 stolen bases. The Pittsburgh Courier referred to Carr as “the most improved player of the league” and “without a doubt the sensation of the Eastern circuit this season.”11 His efforts helped Hilldale to the Negro League World Series rematch in which they whipped the Monarchs, winning five of six games. Carr batted .308 with one homer and six RBIs in the World Series. In California in the winter, he claimed another title by leading the Philadelphia Royal Giants to the Winter League championship with a league-leading 8 home runs and a .342 batting average.

Carr was at his peak, both in the ECL and CWL, from 1924 through 1926. In a total of 563 at-bats, he hit .355 with 50 doubles, 15 triples, 30 home runs, and at least 24 stolen bases (though likely more, as stolen-base statistics from the CWL are unavailable).

The Daisies again had the best record in the ECL in 1926, although the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants represented the circuit in the Negro League World Series that year. Carr contributed a .315/.412/.441 slash line and a 132 OPS+ as Hilldale finished 53-33-2 (a .616 winning percentage). In the offseason, he opted for a change of scenery and spent his winter in Cuba. Carr did not play in the Cuban Winter League but in the “independent league known as Triangular – because 3 teams were in competition – [that] conducted its games at the University of Havana Stadium, showcasing the best Cuban and imported players of the time, lured from the official league by higher compensation.”12 Carr batted .416 playing for Alacranes, which finished in first place with a 22-15 record.13

In 1927 Hilldale fell to fifth place in the ECL. Carr held up his end on the field, leading the team with a .323 batting average, but all was not well. He was suspended, along with pitcher Nip Winters and outfielder Namon Washington, “for lack of discipline and indifferent playing.”14 After his rough time with Hilldale that season, Carr returned to California, where he batted .377 for the California Winter League champion Philadelphia Royal Giants.

The next April, Carr was traded to the New York Lincoln Giants with Winters because it was “Hilldale’s policy … to get rid of dissatisfied players, and men who won’t stay in condition.”15 Shortly after the season started, the Giants dropped out of the ECL, and Carr moved on to the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants. The ECL folded in June, but the Giants continued to play an independent schedule.16 In 1929 the American Negro League was formed, with many of the same players and teams from the ECL. Carr stayed on with Atlantic City, batting .370 in limited duty before returning to Hilldale for one game.

After 1929, Carr appears to have dropped out of league ball until 1934. In 1930 he reportedly played for the independent Milwaukee Colored Giants.17 In the summer of 1931, he joined the Royal Giants on a tour of Hawaii. During the winter of 1932-1933, Carr played first base and batted .355 for Lonnie Goodwin’s Philadelphia Royal Giants tour of Hawaii, Japan, China, and the Philippines, during which the team won 50 of the 52 games played.18 Among his teammates on the tour were Hall of Famers Mackey and Andy Cooper.19

In the summer of 1933, Carr caught on with the independent Philadelphia Bacharach Giants. Another trip overseas to the Orient was planned for the next winter, but Carr ended up going to Puerto Rico instead, playing in exhibition games.

Carr’s last season in the Negro major leagues was 1934. He began the season with Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars; he had a longtime connection to Bolden that went back to his days with the Hilldale team. But Carr’s tenure in Philadelphia encompassed only a doubleheader on June 8.20 He played first base in both games and collected three hits. It is not known why he left the team, but about a week later he was playing third base for the independent Washington Pilots.21 The players on the Pilots became the primary participants for the Baltimore Black Sox, who entered the Negro National League II in the second half of the season but shut down after limited action. Carr played three games at third base and wielded a still potent bat even though he was approaching age 40 – 6-for-11 with a home run and two stolen bases. His known playing career concluded with player-manager stints for the independent Philadelphia Black Meteors in 1935 and the Philadelphia Colored Giants in 1941.22

Little is known of Carr’s personal life after baseball. Census records from 1940 indicate that he lived in Los Angeles with his wife, Sarah; his son, Ernest; his daughter-in-law, Celia; and two grandsons.23 He was employed as a cook in a café.24

George Carr died suddenly on January 14, 1948, in McPherson, Kansas, of a heart attack while working for the Rock Island Railroad Company.25 He had just recently come into the area for the work.26 He left behind his wife, two children, and four grandchildren.27 Carr was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles. Among the pallbearers at his funeral service were former teammates Mackey, Dobie Moore, Jess Hubbard, and Carlisle Perry.

Despite his showing on the Pittsburgh Courier’s list of all-time Negro League players, Carr has not been mentioned as a Hall of Fame candidate. He was not among those players considered for enshrinement by the 2006 Special Committee on the Negro Leagues. A look at his stats, however, indicates that he may have been worthier of inclusion in Cooperstown than many thought. Carr’s lifetime 129 OPS+ is higher than that of Cool Papa Bell among primarily Negro League players. It’s also higher than the career marks of Hall of Fame first basemen and contemporaries George Sisler and Jim Bottomley. Most winters he traveled home to play in the California Winter League, where he was one of the more accomplished players in the history of the circuit. His .336 lifetime batting average is ninth all-time, and he ranks high on the career lists in doubles, triples, and home runs. Should one downplay the quality of competition in Carr’s Winter League play, it’s important to note that among his contemporaries over 13 seasons were 20 Hall of Famers, both from the Negro Leagues and the White major leagues. If one combines his Negro League and California Winter League appearances, he batted .320 over more than 3,500 plate appearances.

While the numbers demonstrate Carr’s all-around skills, the “intangibles” are a bit mixed. His leadership skills were displayed at a young age when he managed the White Sox in his 20s. He was well liked, and affectionately called “Native Son” in the media and managed local teams after he left league play. His perceived attitude problems at the end of his tenure in Hilldale and rumors of alcoholism and possible effects on play28 may take away from his on-field exploits.

Carr’s ultimate baseball legacy probably lies in the years when he played for Hilldale. He slashed .316/.380/.473 with a 127 OPS+ over his five years with the team, among the greatest of all time. The headliners of those teams were a group of Hall of Famers – shortstop Lloyd, catcher-infielder Mackey, and third baseman Judy Johnson. Like any baseball dynasty, after that first tier of star power, there was another group of very good players who were crucial to their team’s success. Think of players like Bob Meusel with the 1920s Yankees. Charlie Keller with the 1930s Bronx Bombers, and Hank Bauer of Casey Stengel’s 1950s clubs. Carr’s contributions to the Daisies look similar in context to those of these talented players.

The more one digs into Carr’s career, the more one is impressed by his all-around skills. His place on the Courier list is indeed well deserved.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com and Seamheads.com for player statistics and team records. He also consulted the following:

McNeil, William. The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

Notes

1 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier November 27, 1937: 16.

2 Email exchange with Scott Simkus, January 23, 2023.

3 “Power, Speed, Skill Make All-American Team Excel,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1952: 16.

4 George H. Carr in the 1910 United States Federal Census (https://www.ancestry.com).

5 George H. Carr obituary (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/99620094/george-henry-carr).

6 George Henry Carr World War II Draft Registration Card (https://www.ancestry.com). Universal City is an unincorporated enclave within Los Angeles.

7 Hilberte L. Rozier, “Thoughts Wise and Otherwise,” California Eagle, October 14, 1916: 8.

8 “Base Ball,” Kansas City (Missouri) Sun, May 29, 1920: 8.

9 “Monday’s (Decoration Day) Game,” Kansas City Sun, June 5, 1920: 8.

10 Lawrence Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African American Baseball (Washington: National Geographic, 2006), 166; John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 221, 332.

11 W. Rollo Wilson. “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 12, 1925: 13.

12 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 171.

13 Figueredo, 171-72.

14 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 157.

15 “Lincolns and Hilldales in Big Trade: Nip Winters and George Carr Leave the Clan of Darby,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 21, 1928: 17.

16 Center for Negro League Research, www.cnlbr.org.

17 “New Pitcher Added,” California Eagle (Los Angeles), November 21, 1930: 9.

18 Center for Negro League Research.

19 Ancestry.com, accessed January 4, 2023.

20 “Giants Take Twin Bill From Philly: Foster and Trent Hurl Coles to Win,” Chicago Defender, June 9, 1934: 17.

21 “Pilots Beat All-Phillies,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 16, 1934: 15.

22 Center for Negro League Research.

23 Ancestry.com, accessed January 4, 2023.

24 Ancestry.com, accessed January 4, 2023.

25 “Check Death of Negro Man Here,” McPherson (Kansas) Daily Republican, January 15, 1948: 1.

26 “May Hold Autopsy in Negro’s Death,” McPherson Daily Republican, January 16, 1948: 2.

27 George H. Carr obituary (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/99620094/george-henry-carr.

28 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994), 154.

Full Name

George Henry Carr

Born

September 2, 1894 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

Died

January 14, 1948 at McPherson, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.