Bobby Williams

It took a special type of athlete to play for Chicago American Giants manger Rube Foster. He liked to engage in small ball and built his teams around speed and bunting. He wanted only smart competitors on his team. Foster was known to say, “If you haven’t got intelligence enough to fit into this play, you can’t play here.”1 The ideal ballplayer for Foster was someone who was fast enough to steal a base, smart enough to know when to steal that base, and good enough with the bat to lay down a perfect bunt. Bobby Williams fit that role so well that he ended up playing for Foster for eight straight years.

It took a special type of athlete to play for Chicago American Giants manger Rube Foster. He liked to engage in small ball and built his teams around speed and bunting. He wanted only smart competitors on his team. Foster was known to say, “If you haven’t got intelligence enough to fit into this play, you can’t play here.”1 The ideal ballplayer for Foster was someone who was fast enough to steal a base, smart enough to know when to steal that base, and good enough with the bat to lay down a perfect bunt. Bobby Williams fit that role so well that he ended up playing for Foster for eight straight years.

Robert “Bobby” Lawns Williams was born on September 30, 1895, in New Orleans to George and Mary Williams. His father was a day laborer, who owned his own home in the Leonidas area of town. Bobby was the youngest of eight children. Nothing is known of his childhood, but one can imagine his family walking to nearby Lincoln Park to hear musicians like Buddy Bolden play music that eventually became known as jazz.

In the early 1910s, Bobby was a student at New Orleans University. This was a historically Black college that merged with Straight College in 1934 to form what is now known as Dillard University. During his time there, he played on the baseball team with Dave Malarcher, and “[b]etween 1913 and 1916 the baseball team lost not a single game. The success was due to two stars, David Malarcher and Robert Williams, who acted as coaches.”2 Williams eventually teamed up again with Malarcher on the Chicago American Giants from 1920 to 1925.

Prior to each season, the American Giants made a “spring training” trip and played games in the South. While on this trip in 1916, Rube Foster signed Williams, who was then farmed out to the Dayton Giants.3 This team was also nicknamed the Dayton Chappies after catcher-manager-co-owner George “Chappie” Johnson. Johnson was an ideal manager for the 21-year-old Williams. He was “quiet, calm, and dignified, and always showed class and maintained a gentlemanly demeanor, even in his protests with umpires.”4

The American Giants played the Dayton Giants during the 1917 season, and it was then that Foster probably knew he was correct in signing Bobby Williams. A game in June between the two teams saw Williams make “a great one-hand stab of (John Henry “Pop”) Lloyd’s line drive.”5 Williams was a small man, even for the era in which he played, and his playing height was listed at 5-feet-5 and his weight as 145 pounds. It was his speed that likely drew the most attention from Foster

As the 1917 season neared its end, Foster was looking for a new shortstop. Pop Lloyd had been playing shortstop for Foster’s American Giants since 1914. When the 1917 regular season ended, Foster decided to take his team to Palm Beach to play in the Florida Hotel League. However, Lloyd “had a job in the Army Quartermaster’s depot in Chicago, and he decided to stay there instead of traveling to Florida.”6 Even though Lloyd was considered by many to be the best shortstop in all of baseball, his choice to stay behind in Chicago “displeased Foster, and by early spring the manager was singing the praises of a young shortstop named Bobby Williams.”7

It did not take long for the Chicago newspapers to notice Williams. As early as March 2, 1918, the Chicago Defender wrote that Williams was a find and that “Rube Foster has a crack shortstop in Williams, the crack shortstop from New Orleans.”8 On March 30 the paper wrote that “Bobby cut a swath between second and third and the rich fans at the Royal Poinciana are still talking about him.”9

The Royal Poinciana was a Palm Beach hotel that hired porters and waiters based on one qualification: that they played baseball well. Another hotel in the area, the Breakers, also had a baseball team, and the two teams played each other every January through March. Judy Johnson said about playing in Palm Beach: “The rivalry between the two teams was intense, but it was the money-making that lured many of the players down there. The pay and the tips were excellent.”10

As the 1918 baseball season began, the Chicago fans took to Williams quickly. “Never has any player … taken with the fans on such a short stay as little Bobby Williams.”11 In a game against his old team, the Dayton Giants, he “went back near second, leaped in the air, stabbed [Samuel] DeWitt’s Texas leaguer, turned a somersault and still held the ball in his gloved hand.”12 There was some drama on July 6, though. The Chicago Defender ran a story stating that Williams was missing and asked for the public’s help in locating him. The paper feared he had “been kidnapped, lost, strayed or been stolen or perhaps he has fallen the victim of the Black Hand.”13 The Black Hand was a precursor to organized-crime syndicates that extorted its victims with threats of violence.

There is no record of exactly what happened to Williams that day. He must have been located quickly because a week later the news about Williams had shifted to his being drafted into the US Army. The United States had entered the World War in April of 1917 and, although Williams had registered for the draft in late May, he was still caught off guard by actually being called to duty. The Chicago Defender reported that “Bobby was last seen … sitting on the steps of Foster’s home looking like a stray sheep waiting for a message from his draft board.”14

Perhaps because of the uncertainty of war, Williams married Marie Skelton, a schoolteacher from Indianapolis. The marriage took place on August 27, 1918, in Winnebago, Illinois, a small town near Wisconsin. The couple’s union did not last long; by the time the 1930 census was completed, Williams was listed as divorced.

As was the case on baseball teams, Williams spent his time in the Army as a member of a segregated unit. He served in the 803rd Pioneer Infantry Regiment’s Company M, an African American outfit. By September the regiment was stationed at Camp Upton, New York. Williams was promoted to sergeant and then went overseas and served in Brest, France.

Pioneer infantry troops “did everything the infantry was too proud to do, and the engineers too lazy to do.”15 Their duties “were often summarized as building and repairing roads and buildings.”16 They usually provided manual labor to help the Regular Army troops and the engineers.

The 803rd Pioneer Infantry Regiment did see combat in late October at the Toul Sector in France. It is not known how close to the lines they were. Although the 803rd had many casualties, only three members of Williams’s company died. All three deaths were from the influenza epidemic that was spreading worldwide at the time.17

Williams returned home from France in February 1919 on the USS President Grant. This ship was for the “casual sick and wounded,” although it is unknown what ailed Williams enough for him to be transported aboard this vessel. Williams’s World War II draft registration card does mention that he had a scar on his right leg from a wound suffered in World War I. The Chicago Defender also mentioned “Bobby’s overseas injury”18 in reference to his being ready to start the 1920 season on time.

Whatever injury Williams sustained in the war; he was ready to play baseball again in 1919 and was welcomed back to the Chicago American Giants. The April 5 edition of the Chicago Defender, referring to the ballplayers returning from overseas, stated that “they were in good health and expect to be in the game for all it’s worth.”19

The 1919 season saw some significant changes in the American Giants lineup. Center fielder Pete Hill was replaced by Oscar Charleston, and Cristobal Torriente joined the team to play left field. Thus, Williams had the opportunity to learn from some of the best players the Negro Leagues ever saw.

In July of that year, interracial violence erupted in Chicago and “[r]oving gangs of white vigilantes … pulled black commuters from trolleys and beat them, shot people from cars, looted black-owned businesses, and set fire to houses.”20 Eventually, the Illinois National Guard was called out and occupied Schorling Park, the American Giants’ home ballpark which was right in the middle of the riot-torn area. Williams and the rest of the American Giants were in Detroit at the time of the riots, and they found themselves stranded. Rube Foster was forced to plan a trip that had his squad playing teams in the East. The team was not able to play another game at Schorling Park until August 31.

Available statistics indicate that Williams finished the 1919 season with just a .219 batting average. He had 16 RBIs in 42 league games, 12 walks and 5 sacrifice hits. These totals tell the story of how Rube Foster managed the American Giants. He “introduced the hit-and-run play, bunt-and-run, drag bunting, the double steals, the suicide squeeze play and tilting of the base lines for bunt control.”21 Williams appeared to be a seamless fit for this style of play.

On February 13, 1920, the first Negro National League was formed in Kansas City, Missouri. At the center of it all was Foster. His Chicago American Giants joined seven other Midwestern teams to establish stability among Black baseball clubs.

Based on his play the previous year, Williams’s place on the club for the 1920 season was secure. In late March, the Chicago Defender wrote that “the verdict of the fans is that Williams is here to stay and will prove a wonder this season.”22 Joining the American Giants as third baseman was Williams’s old college teammate, David Malarcher. Together, they formed a solid left side of the infield for the next six years.

The Chicago American Giants took the NNL’s inaugural pennant. Williams hit .212 with 26 RBIs in 60 league games. Collectively, the entire team hit for a .254 average, but their 92 sacrifice hits in 62 NNL games played tell the story of how this team won.

The Negro National League games ended in late September of 1920. Instead of playing more exhibition games with the American Giants, Williams joined the Dayton Marcos since that squad was in need of a shortstop. Dayton was in such dire straits that in the game before Williams joined the team, the Marcos had used a pitcher to play shortstop.23 Little is known about Williams’s time with Dayton, but he more than likely played with the team until its season ended in late October.

The year 1921 began with most of the American Giants going to Florida to play at the Poinciana Hotel again. Williams was among the team members who were getting ready for the coming season while also making extra money as porters. He rejoined the American Giants and they once more finished with the best record in the Negro National League. Williams put up average batting statistics, but he did end up with 17 sacrifice hits and 14 stolen bases in 84 league games. In an October 4 game against Hilldale, Williams stole second, third, and home in the same inning and finished with a total of four stolen bases that day.24

The 1922 season was similar to 1921. The American Giants again finished with the best record in the Negro National League. Williams’s statistics were quite similar to what he put up in 1921: a .224 batting average to go with 15 sacrifice hits and 10 stolen bases in 74 league games.

As 1923 began, it was evident that Williams had become a fan favorite in Chicago. The Chicago Defender wrote on January 13 that “in the number of answers we received from the fans that regularly attended the games of the Chicago club, Bobby’s name continued to lead those named as shortstop, 10 to 1.”25 In 75 NNL games, Williams’s batting average rose to a respectable .250, and his sacrifice hits again reached double digits with 12. Even though the American Giants fielded a similar team to the previous year’s, they failed to capture the NNL pennant for the first time, finishing second to the Kansas City Monarchs, who were led by such stars as Bullet Rogan and Dobie Moore.

The American Giants finished second to the Kansas City Monarchs again in 1924. Williams may have had his best year as a hitter. He hit .273 with 50 RBIs in 75 league games. After the NNL season ended, Williams traveled to Cuba to play for the Leopardos de Santa Clara team. The Chicago Defender reported “with … our great little Bobby Williams … at short, the Santa Clara team in the Cuban league has jumped from the bottom to second place.”26 Led by the hitting of Alejandro Oms, Santa Clara finished in third place. Other players on the team included Oliver Marcell and future Hall of Famer Turkey Stearnes.

The Chicago American Giants returned for the 1925 season with pretty much the same lineup as the previous year’s. Without any significant changes, the team fell to third place. The Monarchs once again took the pennant, while the St. Louis Stars finished in second place. Williams, playing in 85 NNL games, led the league with 25 sacrifice hits.

The 1926 season proved to be a tumultuous one for Williams. The Indianapolis ABCs, after seeing many of their star players leave for teams in the East, were in desperate need of players. Rube Foster agreed to have Bingo DeMoss leave the American Giants to manage the ABCs. DeMoss wanted to take Williams with him, but Williams did not want to leave Chicago. In late March, the Negro National League held a meeting of its board of directors. The Chicago Defender reported that DeMoss “may be detained here a few days longer dickering for the services of Bobby Williams.”27

Williams reluctantly joined the Indianapolis club. However, by mid-May, he jumped his contract to play for the independent Homestead Grays, based in the Pittsburgh area. Frank “Fay” Young, sports editor of the Defender, did not take this news well. He wrote, “It looks bad for Bobby. Besides being outlawed by both league clubs, Bobby has begun to slip in his playing ability, according to those who follow the game day to day. Most of the Chicago fans were more than glad to see him leave the line-up and Foster replace him, but they hoped the change would do the little fellow some good.”28

If Young was correct about the Chicago fans’ observations, Homestead fans nevertheless felt the exact opposite about Williams. The June 10 edition of the New Castle News (from New Castle, near Pittsburgh) reported that “the short-stopping position is in the hands of a star.”29 Williams must have loved switching teams, as the Homestead Grays won 43 straight games and finished with a record of 140-13-10.30 The team was owned and managed by Cum Posey and was led by Hall of Fame pitcher Smokey Joe Williams.

Playing for the Grays had additional advantages. After the 1926 season ended, Bobby Williams traveled to Florida to play with Smokey Joe in the Florida Hotel League. Although information on these games is limited, it seems that he performed well and, at one point, may have managed the Breakers team.31

Williams remained with the Grays in 1927. By now, after playing with elite Negro baseball teams for 10 years, he was showing veteran leadership. None other than Cum Posey felt that Williams was shaping into a manager. Posey wrote, “(Sam) Streeter is no longer with the Grays but Bobby Williams has found his voice and is chief ‘pusher.’”32 The Grays once again played great baseball, but since most of their games were against other independent teams, semipro teams, and town teams, only limited statistics are available. After the Grays’ 1927 season ended, Williams once again played for the Breakers Hotel in Florida.

After returning from Florida, Williams learned that he had been released by the Grays.33 Posey believed he had found a shortstop “whom the management thought would fit into the Grays’ style of play more aptly.”34 That shortstop was Charley Radcliffe, who was, at 21, a lot younger than Williams. According to the Pittsburgh Courier, “besides being a flash afield, he wields a wicked bat.”35 Williams did not waste any time finding new employment; he rejoined the Chicago American Giants to start the 1928 season. Perhaps because he was older, or perhaps because the Giants wanted catcher Pythias Russ to switch to shortstop, Williams found himself moved to third base. Before too long, it was evident that there was no spot on the field for him to play. In early July Williams was sent to the Cleveland Tigers.

The Tigers lost a lot of games during the first half of the 1928 season, and at the time Williams joined the team, owner M.C. Barkin fired manager Frank Duncan and released several players. The Tigers continued their losing ways and ended the season in seventh place. By August, Williams already had left the team to join the New York Lincoln Giants of the Eastern Colored League.

Williams spent the 1929 season playing for the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants of the American Negro League. He started out slowly, failed to hit, and was used mainly as a backup infielder. The team finished 21-50-2, in fifth place in the six-team league.

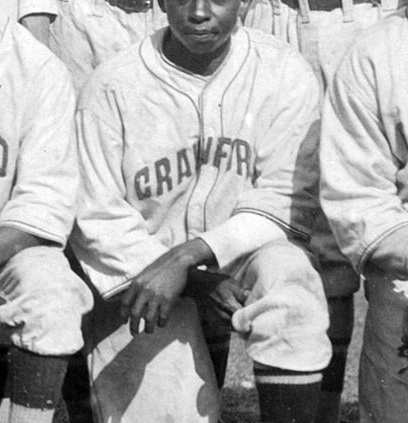

After retiring from baseball in 1930, Gus Greenlee asked Williams to manage his Pittsburgh Crawford Giants for the 1931 season. Greenlee, known for being a numbers runner and racketeer, had just purchased the baseball club and was determined to put together a great team. Williams gathered up exceptional players including Jimmie Crutchfield, Jasper “Jap” Washington, Sam “Lefty” Streeter, and Satchel Paige. As good as this team was, Greenlee was determined to make the next season’s roster even better.

The Homestead Grays, the other Negro League team in Pittsburgh, had a great team in 1931. Greenlee decided to sign away all the Grays’ best players for his Crawfords and accomplished his plan by offering far more money than Grays owner Cum Posey could afford. The first to sign was Oscar Charleston, who managed the Crawfords in 1932. Bobby Williams gave up his managing duties but stayed on the team as a backup infielder. Also joining the Crawfords were Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Smokey Joe Williams, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Judy Johnson, and Josh Gibson. Williams played with seven future Hall of Famers that year. Greenlee Field, the new home of the Crawfords and one of the first Black-built and Black-owned ballparks, also opened that year.

The 1932 season turned out to be Williams’s last year as a professional baseball player. By June the Pittsburgh Courier was reporting that “manager Oscar has been looking all around the country for a hale and hearty third baseman to help out Bobby Williams and his aging legs.”36 Williams finished the season batting only .140 with a .204 on-base percentage.

During the offseason, Greenlee sometimes hired his players for odd jobs. Ted Page, for instance, was hired as a lookout man at a numbers house. He was paid $15 a week to ring a bell if he saw anyone suspicious coming.37 Although no evidence has been uncovered that shows Bobby Williams working a similar job, based on his future arrests, it seems that it was around this time that Williams was introduced to the illegal numbers lottery.

After taking a year off from the game, Williams was back in baseball in 1934. He now managed the Cleveland Red Sox of the Negro National League II. The Pittsburgh Courier felt that this was a good hire, describing Williams as “quiet, unassuming, but possessing a thorough knowledge of the game”38 But the team played poorly and finished in last place with a 3-22 record. The team folded after the season ended.

On August 13, 1938, Williams played in the Homestead Grays’ 25th anniversary baseball game. The team, made up of former Grays, played an all-White team of retired players at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Besides Williams, other former Grays who participated included Smokey Joe Williams, Jap Washington, and Sam Streeter, all of whom contributed to the Grays’ victory that day.

In 1945 Williams took the job of managing the reconstituted Pittsburgh Crawfords of the newly formed United States League.39 The league was the brainchild of Gus Greenlee and had the backing of Brooklyn Dodgers minority owner and general manager Branch Rickey, who ostensibly wanted to use the new circuit to scout Black players whom he might sign to break White baseball’s color line. Other former players who managed teams in the league included Oscar Charleston, Dizzy Dismukes, Bingo DeMoss, and Webster McDonald. The league’s games did not receive much press coverage, but the Crawfords were reported to have won the championship.40 The USL did not last past the 1946 season.

Williams continued to live in Pittsburgh after his baseball career was over, but he did not find the same success that he had found on baseball diamonds. Between 1947 and 1961, he was arrested five times for running numbers.41 He was essentially a bookie who took money for bets in an illegal lottery.

One bright spot in Williams’s later years occurred when he was selected to vote in the 1952 Pittsburgh Courier Poll of Greatest Black Players. He was one of 31 experts, including 21 former players, who voted for the best Negro League players from 1910 to 1951. This poll is frequently referenced when baseball historians attempt to determine who the greatest players in the Negro Leagues were. Williams received one vote. It is not known if he voted for himself; there is only one known ballot, and it is not Williams’s.42

Sometime between 1958 and 1963, Robert Williams married Helen Butler. Helen owned the home that Robert had lodged in since at least 1940. She was a widow whose first husband had died of tuberculosis in 1936. She had a daughter, Shirley, from that marriage. Robert must have formed a close bond with Shirley because he is listed as her father in his obituary.

Robert Williams died on December 30, 1978, in Pittsburgh at the age of 83. He was buried in Allegheny Cemetery, where Josh Gibson, his former Hall of Fame teammate, also is buried.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank fellow SABR members Bill Nowlin, Frederick C. Bush, and Thomas Kern, who took the time to answer emails about Bobby Williams’s obituary. In addition, the author thanks Cassidy Lent, manager of reference services at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, who provided Williams’s file and Hall of Fame questionnaire.

Sources

Ancestry.com was consulted for public records, including census information, birth, marriage, and death records, and military registration cards.

Unless otherwise indicated, all statistics and team records were taken from the Seamheads Negro League Database.

Notes

1 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 25.

2 John B. Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues, Revised Edition (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2010), 45.

3 “Trio of American Giants,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 14, 1925: 7.

4 Negro Leagues Baseball eMuseum: Personal Profiles: George “Chappie” Johnson https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/johnsonch.html. Accessed December 15, 2021.

5 “American Giants Continue to Win,” Chicago Defender, June 9, 1917: 8.

6 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 77.

7 Peterson, 77.

8 “Williams Is a Find,” Chicago Defender, March 2, 1918: 7.

9 Mister Fan, “American Giants to Present New Line-up for This Season,” Chicago Defender, March 30, 1918: 9.

10 William E. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2015), 28.

11 “Williams Drafted: Mendez Shortstop,” Chicago Defender, July 13, 1918: 9.

12 “Fosterites Win 2 from ‘Chappies,’” Chicago Defender, June 22, 1918: 13.

13 “Twilight Game to American Giants in Eleventh,” Chicago Defender, July 16, 1918: 9.

14 “Williams Drafted: Mendez Shortstop.”

15 Margaret M. McMahon, A Guide to the U.S. Pioneer Infantry Regiments in WWI (Middletown, Delaware: Margaret M. McMahon Teaching & Training Company, 2018), 4.

16 McMahon, 37.

17 This information was obtained via the Fold3 Military Records website. See www.fold3.com.

18 “Nothing Lacking to Make Giants Great; ‘Rube’ Has Fine Team by All the Dope,” Chicago Defender, April 10, 1920: 11.

19 “Giants’ Recruits Work Hard,” Chicago Defender, April 5, 1919: 11.

20 Gary Ashwill, “White Racial Violence and the Negro Leagues: The Chicago Riot of 1919,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2020/06/white-racial-violence-the-negro-leagues-the-chicago-riot-of-1919.html, accessed December 15, 2021.

21 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in His Time (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012), 102.

22 “Bobby Williams, Shortstop,” Chicago Defender, March 27, 1920: 11.

23 “St, Louis 6, Dayton 0,” Dayton Herald, September 18, 1920: 16.

24 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 161.

25 “Lyons, Torrienti, and Jim Brown Sign with A.M. Giants,” Chicago Defender, January 13, 1923: 10.

26 “First Pictures of Cuban Baseball,” Chicago Defender, November 29, 1924: 10. It should be noted that two books by Jorge Figueredo (Cuban Baseball, A Statistical History, 1878-1961, p. 160, and Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961, p. 361) that are often consulted for their reliability and thoroughness appear to be in error about the identity of the player named Williams who played for Santa Clara during the 1924-25 season. Figueredo identifies the player as Charles Williams in his Statistical History and as Charles A. Williams in Who’s Who. According to the Seamheads Negro League database, there was only one Negro League player named Charles Williams, a second baseman who participated in five games with the Boston Resolutes in 1887. Seamheads lists no player named Charles A. Williams, but does list a Charley Raymore Williams, who was a second baseman with the Chicago American Giants from 1926-30. The common surname Williams and the fact that the two players both were members of the American Giants at times has likely led to the confusion. In addition to the Chicago Defender article of November 29, 1924, this author located a passenger list for the S.S. Cuba, leaving Havana on January 20, 1925, and arriving in Key West the same day. Bobby Williams was listed among the ship’s passengers along with Oliver Marcell and Norman “Starmes,” [sic] (Norman “Turkey” Stearnes; both men played on the Santa Clara team. The preponderance of the evidence points to the Chicago Defender article being correct in naming Bobby Williams as the player who was on the 1924-25 Santa Clara squad.

27 “Jim Taylor to Manage Cleveland: Move Comes as Big Surprise to St. Louis Ball Fans as Directors Meet,” Chicago Defender, March 20, 1926: 11.

28 “Fay Says,” Chicago Defender, May 15, 1926: 8.

29 “Grays to Play Ellwood Friday,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, June 10, 1926: 21.

30 Cum Posey, “The Sportive Realm,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 19, 1927: 17.

31 The Sportive Realm.”

32 Cum Posey, “The Sportive Realm,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 16, 1927: 16.

33 “New Shortstop to Appear in Lineup with Poseymen,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 18, 1928: 30.

34 Posey, “The Sportive Realm,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 24, 1928: 17.

35 “Charley Radcliffe and ‘Bobo’ Leonard New Acquisitions,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 7, 1928: 17.

36 W. Rollo Wilson, “Philly Sees Some Western Ball,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 11, 1932: 14.

37 Holway, Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 159.

38 “Bobby Williams to Manage Cleveland,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 14, 1934: 13.

39 This Crawfords team was a completely new squad that had no relation to the previous iteration of the Crawfords. Greenlee had sold the original Crawfords franchise after the 1938 season, and the new owner moved the team first to Toledo and then to Indianapolis before it finally folded.

40 “United States League (1945-1946),” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, cnlbr.org. http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/United%20States%20League%20(1945-1946)%202019-10.pdf , accessed December 15, 2021.

41 For Williams’s arrests, see the following: “Numbers Suspect Freed as His Pal ‘Takes the Rap,’” Pittsburgh Press, November 25, 1947: 19; “Marauders Strike at Nine Places,” Pittsburgh Press, June 1, 1948: 2; “Three Alleged Numbers Writers Held,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 1, 1956: 16; “Hill Project Foils Raids on Numbers,” Pittsburgh Press, January 14, 1957: 2; “Dream Numbers Bad for Man,” Pittsburgh Press, June 12, 1961: 2.

42 J. Fred Brillhart, “An Analysis of the 1952 Pittsburgh Courier Negro League Baseball Poll,” The Donaldson Network, http://johndonaldson.bravehost.com/pdf/00237.pdf Accessed December 15, 2021.

Full Name

Robert Lawns Williams

Born

September 30, 1895 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

December 30, 1978 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.