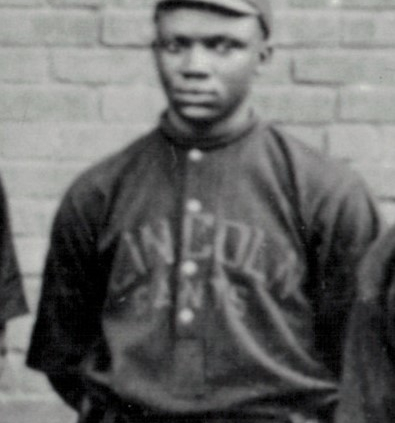

Judy Gans

As a ballplayer, Judy Gans is a bit of an enigma. On the one hand, his official statistics paint him as a good, but not great, player. On the other, acknowledgment of his greatness by newspaper writers and his peers can be found scattered throughout the early pantheon of Black baseball history. Hall of Fame manager Wilbert Robinson referred to Gans as “the colored Ty Cobb.1 Hall of Fame manager Bill McKechnie once claimed that there were at least 25 Black players who could play for any team in the country, and mentioned Gans by name, along with Bullet Rogan, Oscar Charleston, Satchel Paige, and Josh Gibson.2 While playing for the Paterson Smart Set in 1912, Gans was touted as a rival of Home Run Baker,3 which was high praise for a player whose name has been all but forgotten when the greats of the game are talked about.

Robert Edward Gans was born on July 16, 1886, most likely in Cleveland, Ohio.4 His father was Zechariah Gans and his mother was Sarah. Both are listed as being from Pennsylvania in the 1920 census. His 79-year-old mother and sister, Barbara Newman were living in Cleveland in 1944 when Gans met them for a publicized visit.5 Zechariah’s fate is unknown.

Gans could have just as easily been a football star and his athletic prowess was on display for some of the best professional White teams in Buffalo in 1908, 1909, and 1910. He saw action with the Oakdales and the Black Rock Cycle Club, and played alongside fellow blackball great Pete Hill on a Pittsburgh-based team, the Fighting Tenth.6 Between 1905 and 1910 Gans shuttled back and forth between his two loves, football and baseball. While playing in his hometown of Washington, Pennsylvania, he was later compared favorably to local gridiron star Charlie West, who in 1922 was the first African American to play quarterback in a Rose Bowl.7

Gans also made a name for himself by training White baseball teams in Ohio and Western Pennsylvania during this time. The left-handed Gans pitched batting practice and hit fungoes and was with a ballclub in Canton, Ohio, when he got his big break. In 1907 Bill McKechnie was playing third base for an Ohio-based team and persuaded manager Ed Murphy to give the young trainer a whirl on the mound during an exhibition game with the Nebraska Indians. The first batter doubled, the next walked, and the third was hit by a pitch. It was not the most auspicious start, but Gans quickly settled down and struck out the next 12 hitters. The barnstorming Nebraska Indians were impressed enough to sign him, thus beginning Gans’s long, illustrious baseball career.8

Gans next showed up in the press in 1908 as a starting pitcher for the Cuban Giants in the National Association. In a mid-August game, he went the distance in a 5-1 victory over a team from Atlantic City; he also chipped in with two hits.9 In October, in what must have been a thrill, the 22-year-old Gans signed on with a team calling itself the Brooklyn Royal Giants and steamed to Cuba to play against teams from Habana and Almendares. In 16 games the Giants broke even with an 8-8 record, and Gans fared well on the mound with a 2-2 mark and a 2.73 ERA. One of his victories was a hard-fought 2-1, complete-game masterpiece against the Habana Club. His batting skills had not caught up with his pitching quite yet, and he hit a miserable .095 (2-for-21) on the trip.10 Gans must have taken to Cuba because he next hooked up with a team from Matanzas, losing two games with a respectable 3.00 ERA for the fourth-place squad.

After a final interlude with football, with the Fighting Tenth, Gans began the 1911 season with the Cuban Giants. Soon afterward he settled in with the team that he spent most of his career with, the Harlem-based New York Lincoln Giants. This was a powerhouse team in its inaugural season of 1911, and featured such superstars as Louis Santop, George Wright, John Henry Lloyd, Spottswood Poles, and Dick “Cannonball” Redding. As the starting center fielder, Gans hit .308 and stole five bases in 10 games.11

What was known as the kidnapping of players was a popular pastime for owners of Black ballclubs of the time, and Dick Coogan, White owner of the Paterson Smart Set of New Jersey, was one of the best. In 1912 he managed to “kidnap” Gans and pitcher Danny McClellan from the Lincoln Giants to stock his already formidable club.12 The Smart Set team was a short-lived but highly competitive outfit, and this was the team for which Gans took off as a hitter. In 19 games, against all competition, Gans stroked 23 hits for a .351 average, including 6 triples, 4 home runs, and 23 runs scored. He also played stellar defense in left field with 41 errorless putouts and 8 assists.13

What should have been a highlight of the 1912 Smart Set season was marred by controversy when the team met the major-league New York Giants in a late May contest at Olympic Park in Paterson, New Jersey. With the hard-fought bout tied 3-3 after nine innings, interim Giants manager Wilbert Robinson argued with the umpire about the introduction of new baseballs for the 10th inning. He pulled his players off the field in protest, causing the game to be forfeited in favor of the home team. Regardless, the Smart Set proved they belonged on the same field as the legendary Giants, and Gans was the star of the show for the Paterson team. He knocked out two hits, including a double, and played outstanding defense in left, as he recorded six putouts, including a running one-handed grab of a blast off the bat of Giants shortstop Art Fletcher.14

The Smart Set were a scorching 24-7-2 going into late July when Gans was once again “kidnapped” and returned to the Lincoln Giants.15 The Smart Set struggled the rest of the way, going 12-7-1 without him.16 Coogan attempted to “kidnap” Gans again to begin the 1913 season, but Gans was now a fixture with the mighty Lincoln Giants.17

The 1912 and 1913 Lincoln Giants had stars at every position on the field. Joining the already-stacked 1912 team were first baseman Bill Pettus and Hall of Fame hurlers Cyclone Joe Williams and Ben Taylor to form what could only be called one of the greatest baseball teams ever assembled.18 The Giants finished with the best record among all the top Eastern Independent Clubs with Gans acquitting himself nicely by getting on base frequently and showing good speed on the basepaths.

Another trip to Cuba was in the cards for Gans and the Lincoln Giants for the 1912-1913 winter season. Things started off slowly for the team as it played 13 games against Almendares and Habana and struggled to a 5-8 record.19 According to Pop Lloyd, the departure of many of the Lincoln players and the failure of some to show up caused the five Giants – Lloyd, Spottswood Poles, Dick Redding, Cyclone Williams, and light-hitting Bill Francis – to jump to the Fe team for the remainder of the season. With the addition of these players, the Fe squad won the Cuban National League championship.20 Gans was certainly a big reason for its success as he pounded the ball to the tune of a .356 batting average, with 4 three-baggers and 19 stolen bases. The team stole an amazing 136 bases in just 34 games and as it drove the opposition batty with its speed.

A curious side note to the 1913 season had Gans, Cyclone Joe Williams, and Grant “Home Run” Johnson all beginning the year with the Schenectady Mohawk Giants, a first-year and short-lived team that played against Eastern Independent squads such as the Lincoln Giants, Brooklyn Royal Giants, and Paterson Smart Set. All three players were back with the Lincoln Giants just a few weeks after the start of the season.21

The Florida Hotel League or Coconut League was a highly competitive rivalry between two hotels in Palm Beach, Florida, that stocked their teams with some of the best players in Black baseball history. Gans’s first appearance in the league was in 1912, and by January of 1914 he was a veteran of the circuit.22 His team, the Breakers Hotel, featured legends Bruce Petway, Pete Hill, John Henry Lloyd, Louis Santop, and Cyclone Joe Williams. Their rivals, the Poinciana Hotel, included Spottswood Poles, Dizzy Dismukes, Bill Pettus, and Frank Wickware.

Gans’s defense stood out in one 1914 contest. According to the Palm Beach Daily News, “Gans, in the left garden, deserves great credit for the showing he made and the four flies he pulled down. He had to show great speed to get under them in the first place and in all but one instance after he got his hands on the ball he landed in a heap. Twice he stumbled over the mounds near the tall coconut trees and the other time he came in from deep left and gathered in a short fly that many thought he did not catch.”23 The Breakers captured the 1914 title, winning nine games and losing six.24

Gans fell in with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants next, after being invited, along with Cyclone Joe Williams and John Henry Lloyd, to join the team on a trip to the Pacific Northwest. All three players took up Foster’s offer and were scheduled to compete against teams in the Pacific Coast League. At the last minute, PCL President Allen Baum objected to Black players playing against PCL teams, which effectively canceled most of their schedule. The Portland Beavers were the only team to go against Baum and play Foster’s team.25

Gans immediately got into hot water with his new boss. He recounted the story thusly:

It was a damp day. Petway was on second and two were down and I was at bat. Rube signals for me to lay one down. Higginbottom, a lefthander, was working for Portland and Rube figured that if he tried to field the ball and turn to throw me out at first Petway could score. Well, Petway started up on the pitch, the ball was in the alley, and I knocked it into the bleachers for a home run. As I reached the plate with the winning score, as it later proved to be, George Moore, the fight manager, handed me a fifty-dollar bill and other fans threw money at me amounting to $87.50 all told. I went on to the bench and Rube drawled, “That was a sweet hit, son.” “Yes, I sure laid into that one,” I said. “Boys told me you could hit,” added Rube. “Got yourself some money too, didn’t you?” “Yes sir,” I answered. “Suppose you wait for me to check up after the game and we’ll go back to the hotel together,” said the boss. I was getting all puffed up and saw myself getting a feed on Rube as we got in a taxi together. He threw his arm back of me and started to talk. “How did you like working for Sol White down east? Do they have any discipline down there?” “Oh, so so,” as I lolled in my seat. “By the way, son, how much money did you collect?” And I told him $87.50. “Well, boy, let papa tell you something. If the Giants had lost that game today, the paper would have been full of what happed to Rube Foster’s team. I am the manager of the club. I told you to lay it down and you hit a home run. Son, that home run is gonna cost you that $87.50 and $25 more. Now, the next time you hit a home run when I tell you to bunt, you’ll remember that, won’t you?” 26

The 1914 Chicago American Giants were a dominant team with a sparkling 43-14 record, and they easily outpaced the second-place Indianapolis ABCs among the top Western Independent Clubs. Gans uncharacteristically struggled, hitting only .243 with one home run in 169 at-bats.

The following season he was back in familiar territory, but with the Lincoln Stars, an offshoot of the Lincoln Giants, formed when the owners of the Giants lost control of the team.27 By the end of August, Gans and Lloyd found their way back to the Chicago American Giants to finish out the 1915 season when the owner of the Stars was unable to pay them after drinking away all of his profits.28 The American Giants also made an appearance in the California Winter League and bested their White competitors, 9 games to 5. It was a historic occasion as it marked the first time an all-Black baseball team had won the California Winter League championship. In spite of his team’s success, Gans struggled again, batting only .158 in 13 games.29

In February 1916 Gans was back in Cuba with San Francisco Park, a team made up of Chicago American Giants players. Gans hit a solid .300 in 15 games, including four multiple-hit games, but the team had a disappointing 5-9-1 record.30 Once the team returned home, it fared much better and again finished with a top mark of 40-26-3. Gans continued his regular-season struggles and lost his starting left-field spot to Pete Hill. He managed to rekindle some of his spark on the mound with a complete-game shutout against the ABCs in June and two complete-game victories in August that included another shutout.31

In 1917 Gans lived a vagabond lifestyle as he jumped from team to team. The season began with a short stint with the Chicago Giants, followed by another with the Indianapolis-based Jewell’s ABCs. In a late July game with the ABCs, Gans was credited with 20 putouts while manning first base.32 The 1917 season ended with Gans once again suiting up for the Lincoln Giants, this time patrolling center field.

The year 1918 started off well enough for Gans as he began to regain his stroke at the plate, but the clouds of war were about to catch up to him and a number of his teammates. Gans was back with the Chicago American Giants when he, Frank Wickware, and first baseman Leroy Grant were drafted and ordered to report between August 1 and August 5.33 An article in the Chicago Defender mentioned Gans’s wife joining him early in the season in anticipation of his enlisting in the US Army.34 She threw a surprise party for her husband on his birthday, attended by many of his teammates and friends, just days before he left for the service.35 It is not known how long Gans and his wife, Emma, had been married at this point, but the 1920 census lists them as living in Chicago with eight other roommates, including fellow baseball star Jose Mendez. Emma, who was from Alabama, was 30 years old at the time. Their union dissolved at some point; the next census indicated that they were divorced and living separately by 1930.

Gans’s stint in the Army lasted less than a year, from July 31, 1918, to May 19, 1919.36 He was a sergeant in the 803rd Pioneer Infantry and received a warm welcome upon his return to the American Giants.37 Gans spent his time during the war in France and told many tales of his experiences overseas, including how the people there were quite familiar with the exploits of the Chicago American Giants.38 Gans was well-known for his ability to spin a yarn, but his gift for gab did not help to keep his team from finishing in second place, nor did it prevent his hitting from declining further as he was able to contribute only an underwhelming .200 average.39 Occasionally he still pitched, and he spun a four-hit shutout against the All Nations Team in late May, shortly after his return from military service.40

The 1920 Chicago American Giants won the inaugural Negro National League championship, easily outdistancing the Detroit Stars and Kansas City Monarchs. The newly minted league was the brainchild of American Giants owner and manager Rube Foster. Gans was the starting left fielder for what many consider to be one of the great Negro League teams of all time, but his play on the field was less than stellar as he hit a meager .208 for the champs. However, Gans occasionally chipped in, as he did on June 19, when he swatted a two-run home run and a double in a 10-5 victory over the Oak Parks.41

Gans was traded to the Detroit Stars for speedster Jimmie Lyons in December of 1920, but does not appear ever to have played for owner Tenny Blount’s team.42 In an attempt to create equity among the NNL’s teams, newspapermen were chosen to select players for the 1921 squads, which took roster-building out of the owners’ hands. As a result, Gans remained with the American Giants and Lyons with the Stars for the time being.43 In a show of how fluid these teams’ rosters often were, Lyons ended up as a member the 1921 American Giants anyway and Gans moved back to the Lincoln Giants, where he finished out the remainder of his career.

The 1921 and 1922 seasons were solid ones for Gans, as he batted .267 and a resurgent .333 respectively. But the team struggled to play .500 ball. Gans now spent more time at the right-field position. His entire 1923 season was lost when on April 22 he broke his right leg with a triple compound fracture. He had fractured his left leg in 1921 and these two injuries effectively ended his ability to be a productive player.44

Gans accepted a new challenge for the 1924 season when he replaced Cyclone Joe Williams as the manager of the Lincoln Giants. Hopes were high for the season after owner James J. Keenan invested heavily in the team by adding new players and turning Protectory Oval, the team’s home ballpark, into a big-league-quality facility.45 The May 31 edition of the New York Age asserted, “The fans now realize that under Judy Gans the team has improved 100 percent.”46 But the team did not quite live up to expectations and finished in third place. The poorer-than-expected performance was due in part to the numerous injuries to the pitching staff, which led to the 37-year-old Gans taking the mound on more than one occasion.47

The Lincoln Giants fell apart in 1925, and Gans lost control of his team. Allegedly, at the start of the season he had advised the owner of the Giants to cut the pay of some players and to release Gerard Williams and Benny Wilson because they wanted more money. This failed to go over well with players in the league and, whether it was true or not, they refused to sign with the Giants.48 As a result, the team’s roster was decimated. Quality pitching was in especially short supply, and the Lincoln Giants’ team ERA ballooned to 8.24. It came as no surprise that the team finished in last place in the Eastern Colored League, with a woebegone 7-41-2 record. In mid-August, with the team sitting at 3-31-2, Gans resigned as manager.49

Gans was unable to stay away from baseball for long, and he took on a variety of projects. In 1927 he managed the Eastern Colored League All-Stars, a formidable independent team; a newspaper referred to him as crafty and jolly.50 He also pitched for Chappie Johnson’s Stars and in 192851 played for Louis Santop’s Broncos, for whom he mashed seven hits in two games.52 It was rumored that Gans would manage the 1928 Cleveland Tigers, but this would never materialize as the Tigers were led by Frank Duncan, Harry Jeffries, and Sam Crawford that season.53

Gans was also at the forefront of a movement to secure more Black umpires for Negro League baseball.54 An editorial in the Philadelphia Tribune in 1927 commented on the problems of White umpires in Black baseball: “Regardless of the reasons for colored ball games having white umpires it is a disgusting and indefensible practice. It will require much thought and perhaps time and money, but the owners of ball clubs owe it to their patrons to discontinue a practice that is a reflection upon themselves, the ballplayers and the Negro race.”55

Gans himself became a trailblazing Negro League umpire and called his first game in a May 2, 1929, matchup; fittingly, the game involved the Lincoln Giants and the Hilldale Club.56 The pressure must have been immense, as indicated in the April 20, 1929, edition of the Pittsburgh Courier. W. Rollo Wilson wrote, “The whole movement depends on Judy Gans. If he proves the point, then other veterans will be drafted into service.”57 Gans performed well at his new job and was still umpiring as late as 1938.58

Gans was married again in 1937, to Elvera C. Gardiner. The couple remained together until his death in 1949, although very little is known about her.59

In 1940 Gans was recognized as a member of the Brotherhood Civic Goodwill Club in Philadelphia, an organization formed in 1884 to spread goodwill and to urge support to Black businesses and labor.60 In 1944 he was still living in Philadelphia, where he was working as an aerial manager for the US Army Signal Corps.61

Judy Gans died on February 13, 1949, at the Naval Hospital in Philadelphia. His death certificate listed his occupation as bartender. He was buried at the National Cemetery in Beverly, New Jersey.62

Judy Gans’s legacy lived on with Negro League legend and Hall of Famer Judy Johnson who, when elected to the Hall of Fame in 1975, had this to say about his namesake: “One of the old-timers on my first team was named Judy Gans. I resembled him, and my middle name is Julius, so they started calling me Judy too.”63

Dizzy Dismukes – baseball lifer, crafty pitcher, manager, and longtime personnel director for the Kansas City Monarchs – named Gans the seventh-best outfielder in baseball history, ahead of Rap Dixon and Cool Papa Bell, in a 1930 piece he wrote for the Pittsburgh Courier. He insisted that Gans “must be given credit for being one of the game’s greatest fielders.”64 Judy Gans was considered great in his time. He had power, even in the Deadball Era, was known for his speed and exceptional fielding ability, and excelled when called upon to toe the rubber. He played with some of the most iconic teams in Black baseball history, including the 1912 New York Lincoln Giants and the 1920 Chicago American Giants. He was also a pioneering umpire. As with many of the pre-1920 players, his statistics fail to tell the entire story of his career. Judy Gans was a star, and that is how he should be remembered.

Sources

All statistics, unless otherwise noted, were taken from the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database at seamheads.com.

Notes

1 “Manager Shackelton’s Club Will Play Famous Colored Nine on Sunday Morning,” Paterson (New Jersey) Morning Call, July 16, 1914: 3.

2 John B. Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 372.

3 Middletown Orange County Times Press, June 28, 1912.

4 Most sources, including Seamheads.com, list Washington, Pennsylvania, as Gans’s birthplace, but his death certificate and Social Security records list Cleveland as his place of birth. “Ohio” is prominently displayed on his tombstone.

5 “Fined $100 For Making the Home Run That Won the Game,” Cleveland Call and Post, November 4, 1944: 6B.

6 “Judy Gans to Manage Lincoln Gts. This Year,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 7, 1925: 6.

7 Philadelphia Tribune, September 15, 1927: 10. See also https://www.washjeff.edu/100th-anniversary-of-historic-game-by-dr-charles-f-west-the-first-black-quarterback-to-play-in-rose-bowl-game/. Accessed January 2, 2022.

8 “Judy Gans to Manage Lincoln Gts. This Year,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 7, 1925: 6.

9 “Cuban Giants Land,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19, 1908: 11.

10 Severo Nieto, Early U.S. Blackball Teams in Cuba: Box Scores, Rosters and Statistics From the Files of Cuba’s Foremost Baseball Researcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2008), 78-91.

11 Limited box scores are available from this time period and only games against major-league-caliber teams are included in the Seamheads Negro League database.

12 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, August 15, 1912: 6.

13 The author’s own research from Paterson Morning Call box scores, 1912. This includes games against all competition, not just the major-league-equivalent teams as determined by Seamheads.com.

14 “Smart Set Team Played New York to a Standstill,” Paterson Morning Call, May 27, 1912: 3, 13.

15 Lester A. Walton, “Kidnapping Players the Latest Game,” New York Age, August 15, 1912: 6.

16 Author’s own research from Paterson Morning Call box scores, 1912.

17 “Baseball Game at Olympic Park,” Paterson Morning Call, April 1, 1913: 3.

18 The 1912 Lincoln Giants featured four Hall of Famers: Louis Santop, John Henry Lloyd, Joe Williams, and Ben Taylor. The team also included likely future Hall of Famers Dick Redding, Spottswood Poles, and Bill Pettus.

19 Severo, Early U.S. Blackball Teams in Cuba, 105.

20 Wes Singletary, The Right Time: John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2011), 52-53.

21 https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2011/04/schenectady-mohawk-giants-1913.html. See also Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), April 22, 1913: 11.

22 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2007), 16.

23 McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, 18.

24 “Baseball Season Ends on Florida Fields,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 18, 1914: 21.

25 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2007), 48.

26 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 2, 1929: A6.

27 https://thebrooklyntrolleyblogger.blogspot.com/2020/10/a-team-grows-in-harlem-new-york-lincoln.html.

28 Debono, The Chicago American Giants, 57.

29 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002), 54-55.

30 Severo, Early U.S. Blackball Teams in Cuba, 206-217.

31 “Gans Scores Shutout,” Chicago Examiner, June 20, 1916; “Baseball,” Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1916: B22; “Amer. Giants, 6; St. Louis, 3,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1916: 11.

32 “Hoosier Ball Club Wins Ten Round Go From Fosters, 5 to 4,” Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1917: 11.

33 “Draft Hits Rube Foster’s Club Hard,” Chicago Defender, July 27, 1918: 9.

34 “Williams Is a Find,” Chicago Defender, March 2, 1918: 7.

35 “Judy Gans Surprised,” Chicago Defender, July 27, 1918: 9.

36 Ancestry.com: Military Burial Records.

37 Ancestry.com: Find a Grave.

38 “Giants Recruits Work Hard,” Chicago Defender, April 5, 1919: 11.

39 “Pow Wow Pickups,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 10, 1938: 13.

40 “American Giants Blank All Nations,” Chicago Defender, May 31, 1919: 11.

41 “Oak Parks Lose, 10-3,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1920: A3.

42 “Jimmy Lyons Comes to American Giants,” Chicago Defender, December 11, 1920: 6.

43 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in His Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2012), 115.

44 “Judy Gans to Manage Lincoln Gts. This Year,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 7, 1925: 6.

45 “Many New Players in Lincoln Giants Line-Up,” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier-News, March 14, 1924: 16.

46 “Lincoln Giants Set Pace for Eastern League Flag Race,” New York Age, May 31, 1924: 6.

47 “Giants and Hilldale Divide Doubleheader,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 30, 1924: 13.

48 William E. Clark, “Sport Comment,” New York Age, July 3, 1925: 6.

49 “Judy Gans Resigns as the Manager of the Lincoln Giants,” New York Age, August 22, 1925: 6.

50 “Gans’ Stars Downs Trenton with Hackett on Mound,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 25, 1927: 10,

51 “Hilldale Pries Off Lid with Victory,” Wilmington (Delaware) Evening Journal, April 15, 1927: 27.

52 “Lou Santop’s Broncos Win from Red Sox,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 14, 1928: 11.

53 “Bingo DeMoss to Manage Detroit; Gans to Tigers,” Baltimore Afro American, March 3, 1928: 1.

54 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 21, 1928: A4.

55 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing & Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 200.

56 “Hilldale Loses to Lincolns, 4-3, in Opener,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 4, 1929: A5.

57 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 20, 1929: B5.

58 Chester L. Washington Jr., “‘Sez Ches,’” Pittsburgh Courier, April 23, 1938: 17.

59 Ancestry.com: US Marriage Index.

60 “Brotherhood Holds Its 56th Anniversary,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 17, 1940: 3.

61 “Fined $100 For Making the Home Run That Won the Game,” Cleveland Call and Post, November 4,1944: 6B.

62 Ancestry.com: Certificate of Death.

63 “Johnson Selected to Hall,” Charlotte Observer, February 11, 1975: 23.

64 “Dismukes Names His 9 Best Outfielders,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 8, 1930: 14.

Full Name

Robert Edward Gans

Born

July 16, 1886 at Washington, PA (USA)

Died

February 13, 1949 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.