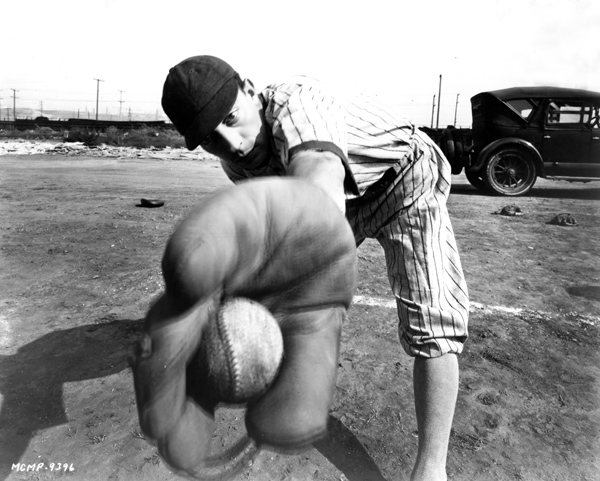

Buster Keaton, Baseball Player

This article was written by Rob Edelman

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Buster Keaton’s journey as a physical athlete starring in silent cinema.

Buster Keaton’s journey as a physical athlete starring in silent cinema.Across the decades, Hollywood stars from Bob Hope and Bing Crosby to Bill Murray and Billy Crystal have been baseball fans. But few were physically adept at playing the game at a high-quality level. One such aficionado-athlete was a comedy legend of the silent cinema, Buster Keaton.

Keaton, who was born Joseph Francis Keaton Jr. in Piqua, Kansas, in 1895, spent his youth touring with his family in vaudeville, appearing in a comic-acrobatic act in which his father tossed him around the stage. The physicality required for the act blended right in with young Buster’s offstage athleticism.

Keaton, who was born Joseph Francis Keaton Jr. in Piqua, Kansas, in 1895, spent his youth touring with his family in vaudeville, appearing in a comic-acrobatic act in which his father tossed him around the stage. The physicality required for the act blended right in with young Buster’s offstage athleticism.

“As far back as I can remember,” he wrote in his autobiography, “baseball has been my favorite sport. I started playing the game as soon as I was old enough to handle a glove. A sand lot [sic] where baseball was being played was the first thing I looked for whenever The Three Keatons played a new town.”[fn]Buster Keaton with Charles Samuels. My Wonderful World of Slapstick. New York: Doubleday, 1960. 154. [/fn] Upon completion of the vaudeville season, Keaton spent tranquil summers at a house his father purchased on Michigan’s Lake Muskegon, and it was here where he really honed his baseball skills.[fn]Tom Dardis. Keaton: The Man Who Wouldn’t Lie Down. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979. 8. [/fn] In fact, present-day Muskegon visitors may play on the same field where, a century earlier, Keaton swung a bat and shagged flies.

By the mid-1920s, Keaton had emerged as one of the screen’s top comic actors, a status that allowed him to oversee the creation of his films. During pre-production, he would ask potential cast members two questions: “Can you act?” and “Can you play baseball?”

“The Keaton Production Company was in fact an ever-ready baseball team, prepared to start a game on a moment’s notice,” reported Tom Dardis, a Keaton biographer. “That moment would often come whenever a production problem arose that seemed to defy immediate solution. Buster would officially declare that a game was in order. If someone had an inspiration halfway through it, the shooting would resume.”[fn]Dardis, 79. [/fn]

While filming at MGM in the late 1920s, Keaton often concluded his lunch break with an impromptu ballgame on a field constructed on the lot. “Half the crew went with him,” recalled Willard Sheldon, an assistant director, “and there were usually problems afterward getting everybody back on the set.” Reportedly, Louis B. Mayer, top man at the studio, considered adding a “no-baseball clause” to Keaton’s next contract.[fn]Marion Meade. Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase. New York: HarperCollins, 2004. 205. [/fn]

“Each September,” Keaton wrote in his autobiography, “I did my best to finish my fall picture in time to go to New York for the World Series.”[fn]Keaton, 154. [/fn]

“Each September,” Keaton wrote in his autobiography, “I did my best to finish my fall picture in time to go to New York for the World Series.”[fn]Keaton, 154. [/fn]

Whenever he could, Keaton took his baseball act on the road. While shooting The General (1927), a Civil War-era comedy, in Cottage Grove, Oregon, Buster paid for the leveling of the turf and the building of a new backstop behind home plate in the town ballyard. To raise funds for the purchase of playground equipment, he played third base for the local Lions club in a game against the Kiwanis.[fn]Edward McPherson. Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat. London: Faber and Faber, 2004. 183. [/fn]

Given Keaton’s love of the game, it is not surprising that he occasionally incorporated baseball into his films—most famously in College (1927) and The Cameraman (1928). In College, Keaton offers a comic takeoff on the game’s basics; The Cameraman features an affecting pantomime of every baseball fan’s dream of standing on the mound or in the batter’s box of a major league stadium.

Keaton stars in College as Ronald, the top scholar in his high school class. At his graduation, he delivers a valedictory speech on the “Curse of Athletics” (which is an inside joke, given Keaton’s real-life baseball obsession). “The student who wastes his time on athletics rather than study shows only ignorance,” Ronald proclaims. Of course, he is not to be taken seriously, as he concludes his sermon by noting, “What have Ty Ruth and Babe Dempsey done for science?”

Upon arriving at Clayton College, Ronald realizes he will have to alter his thinking to win the sports- loving girl he adores. He appears at his school’s ball field and is told to play third base, which he mans garbed in catching attire. The game begins, and a batter hits a grounder that rolls between Ronald’s legs. He avoids a line drive hit his way as if dodging a bullet. A runner tries to steal third base; Ronald misses the ball thrown by the catcher, and is knocked over by the sliding runner. Another grounder is hit to Ronald, which he picks up and holds helplessly. And so the sequence unfolds.

Eventually, Ronald comes to the plate. He tries to limber up by swinging three bats at once, but only succeeds in conking himself in the noggin. As this part of the sequence plays itself out, Ronald eventually is backstop over. After taking first base, he attempts to steal second but promptly trips. The next batter pops up, but Ronald dashes around the bases, past the runners in front of him. He somersaults into home plate, only to be informed by the umpire that he “forced two men out and you’re out, too.” So ends Ronald’s baseball career. Even though the character is supposed to be athletically inept, what makes the comedy work is Keaton’s very real physical dexterity—most noticeably as he rolls into home plate.

In The Cameraman, Keaton plays Buster, a klutz who is a would-be newsreel cameraman. At one point, he trudges out to Yankee Stadium to photograph Babe Ruth and company. But on that day they are playing in St. Louis. What to do? Buster sets his camera down by the pitcher’s mound and pantomimes a hurler about to go into a windup, acknowledging the sign from his catcher, attempting to pick off a runner, shifting his infielders, and handling a double-play ball. He also pantomimes a batter who is almost hit by a pitch, and who then smacks an inside-the-park dinger. He slides headfirst into home plate and waves his hat at the fans, who exist only in his mind.

In The Cameraman, Keaton plays Buster, a klutz who is a would-be newsreel cameraman. At one point, he trudges out to Yankee Stadium to photograph Babe Ruth and company. But on that day they are playing in St. Louis. What to do? Buster sets his camera down by the pitcher’s mound and pantomimes a hurler about to go into a windup, acknowledging the sign from his catcher, attempting to pick off a runner, shifting his infielders, and handling a double-play ball. He also pantomimes a batter who is almost hit by a pitch, and who then smacks an inside-the-park dinger. He slides headfirst into home plate and waves his hat at the fans, who exist only in his mind.

The closest Keaton came to making a “pure” base- ball movie was One Run Elmer (1935), a two-reel comedy released when Keaton was past his prime as an A-list Hollywood commodity. While One Run Elmer is a talking picture, most of its gags are visual. Buster plays a hapless gas station owner who practices ballplaying with a rival. Elmer’s pitches are promptly hit through the windows and walls of his rickety station. When it is his turn to bat, he misses the first pitch, which further destroys his building; he connects on the next toss, which smashes the window of a car whose owner will umpire the following day’s game. Similar slapstick bits follow once that contest starts.

During his time in Southern California, Keaton was at the center of the local baseball scene. His earliest films were one- and two-reel comedies featuring rotund Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. In 1919 Arbuckle purchased a controlling interest in the Vernon Tigers, the Pacific Coast League team that later became the Hollywood Stars. On that first opening day, Arbuckle, Keaton, and other screen comics staged a mock mini-game using a plaster ball and bat. Arbuckle pitched. Al St. John was the batter. Keaton was the catcher. Rube Miller umpired—and a fun time was had by all.[fn]Keaton, 154. [/fn]

Keaton and Joe E. Brown—another ballplaying actor who starred in three Warner Bros. baseball comedies, Fireman, Save My Child(1932), Elmer the Great (1933), and Alibi Ike(1935)—regularly formed their own teams and sought out competition. Both also employed their love of the sport in fundraising ventures. In February 1932 both were involved in a charity benefit for the upcoming Los Angeles Olympics. Over 8,500 fans packed Wrigley Field to watch the Joe E. Browns best the Buster Keatons by a 10–3 score. Their rosters were lined with major leaguers: Rogers Hornsby, Gabby Hartnett, Paul Waner, Lloyd Waner, Sam Crawford, Billy Jurges, Stan Hack, Tris Speaker, Dave Bancroft, Carl Hubbell, Charlie Root, Pat Malone, Johnny Moore, and Pie Traynor, among others.[fn]Rob Edelman. “Joe E. Brown: A Clown Prince of Baseball.” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History. Cleveland: The Society for American Baseball Research, 2007. 127–131. [/fn] Keaton also played in the industry’s annual Comedians-Leading Men contests.

Keaton often employed big leaguers in his films. Sam Crawford plays a baseball coach in College. Mike Donlin appears as a Union general in The General. Jim Thorpe has a bit as a ballplayer in One Run Elmer. Byron Houck photographed a number of Keaton features, while Ernie Orsatti worked for Keaton as a prop man.

While there is no doubt that Keaton was adept at ballplaying, a question arises: Was he good enough to play pro ball? Might he even have made the majors? While there is no definitive answer here, one point is indisputable. “Throughout his life,” observed Marion Meade, another Keaton biographer, “baseball would be his religion.”[fn]Meade, 205. [/fn]

ROB EDELMAN is the author of “Great Baseball Films” and “Baseball on the Web”. His film/television-related books include “Meet the Mertzes”, a double-biography of “I Love Lucy’s” Vivian Vance and fabled baseball fan William Frawley, and “Matthau: A Life” — both co-authored with his wife, Audrey Kupferberg. He is a film commentator on WAMC (Northeast) Public Radio and a contributing editor of “Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide”. His byline has appeared in “Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game”, “Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond”, “Total Baseball”, “The Total Baseball Catalog”, “Baseball in the Classroom: Teaching America’s National Pastime”, and “The Political Companion to American Film”. He authored an essay on early baseball films for the DVD “Reel Baseball: Baseball Films from the Silent Era, 1899-1926”, and has been a juror at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s annual film festival. He is a lecturer at the University at Albany, where he teaches courses in film history.