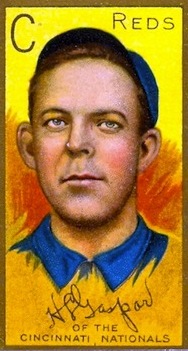

Harry Gaspar

Inveterate business and baseball man Harry Gaspar skipped from Class D straight to the majors by exhibiting inherent talent, self-confidence, and know-how on the pitcher’s mound. Once described as a lanky chap with a devil-may-care air, he put in three quality years (1909-1911) playing for Cincinnati. Then, after a shaky start to his fourth season with the Reds, he slipped down to Double-A Toronto in midseason. For the next decade, he played for and managed a number of Midwestern clubs, from Class A Organized Baseball to small-town amateur. Throughout his career, he gained the following of ball fans wherever he played. Also recognized as a proficient photographer, he operated a successful studio in the Iowa town of Le Mars, where he lived for about 14 years. A second-generation Iowan, he descended from Luxembourg immigrants.

Inveterate business and baseball man Harry Gaspar skipped from Class D straight to the majors by exhibiting inherent talent, self-confidence, and know-how on the pitcher’s mound. Once described as a lanky chap with a devil-may-care air, he put in three quality years (1909-1911) playing for Cincinnati. Then, after a shaky start to his fourth season with the Reds, he slipped down to Double-A Toronto in midseason. For the next decade, he played for and managed a number of Midwestern clubs, from Class A Organized Baseball to small-town amateur. Throughout his career, he gained the following of ball fans wherever he played. Also recognized as a proficient photographer, he operated a successful studio in the Iowa town of Le Mars, where he lived for about 14 years. A second-generation Iowan, he descended from Luxembourg immigrants.

Harry’s paternal grandparents, Nicholas and Catherine (Welter) Gaspar, left their home in Grosbous, Luxembourg, arriving in America in 1846. Settling in Dubuque County, Iowa, a hotbed of early Midwestern baseball, the couple raised eight children while farming there. Their sixth child, John P., married Mary Bain and moved to the little village of Quorn in Plymouth County, Iowa, where he made a living as a grocer. There, he and his wife welcomed their first child, Harry Lambert, on April 28, 1883. The following year, prompted by railroad construction that bypassed their village, the family, along with most of the other 400-some Quorn residents, moved a mile east to the newly established town of Kingsley. Growing up in Kingsley, Harry cultivated his baseball skills on the village green. By the time he started playing for his hometown ballclub, his family included a sister, Ethel, and brothers Edgar and Francis.

Pitching for Kingsley, the tall right-hander first gained the notice of the pros when he won an exhibition game against Sioux City of the Western League sometime in 1905. With baseball already entrenched in Iowa culture, local fans recognized and valued budding talent. In 1909 the Le Mars (Iowa) Sentinel took a look back at the scene leading up to that contest, played at Kingsley’s ballpark. In a buoyant portrayal of young Harry on his way to the game, the writer described him “with a straw hat mounted jauntily on a well-trimmed head” casually strolling down the sidewalk. Not long after that, Harry signed with Dubuque of the Three-I League, but failed to impress and found his way to Wausau and then Freeport of the Wisconsin State League in 1906. Finally, after being traded to the Waterloo Cubs (of the Iowa League of Professional Baseball Clubs) for another player and a few hundred dollars the following year, he drew serious attention.

A long-remembered and much heralded game of 1907 gave Waterloo fans a thrilling look at the new guy on the mound. Describing the event, a local sportswriter saw him as rawboned and awkward, but couldn’t dispute his ability. On September 11, Gaspar methodically worked 11 innings to win a 1-0 no-hitter against Burlington. He wrapped up the season with an 18-9 won-lost record, and the club won the league pennant. In 1908 Gaspar helped usher the same Class D club, then the Waterloo Lulus of the Central Association, to capture that league’s championship. That fall Gaspar was sold to Cincinnati. Of course, he still had to pass the inspection of the Reds’ manager, Clark Griffith.

An article in the Oelwein (Iowa) Daily Register, purported that initially the Old Fox had concerns about the rookie’s readiness for the big leagues. The account supports ongoing evidence of Gaspar’s astute approach to his craft. Supposedly he didn’t have a curveball in his repertoire up to that time. But acting on a tip that Griffith preferred curveball pitchers, he zealously developed one. Displaying it in five consecutive throws on the day of the roster cutdown, he landed a job.

Early in 1909 Reds fans saw real promise in the 6-foot, self-assured slinger from the state where the tall corn grows. In the second inning of an April 17 home game with Pittsburgh, he came in to relieve veteran lefty Ed Karger, who had allowed five runs. Shutting down the opposition, Gaspar worked through the ninth while his teammates helped him register his first big-league win, an 8-5 victory. Sportswriters still regarded him as unpolished, but remarked on his strength and natural ability. By early August, when The Sporting News decried the Cincinnati club’s lack of pitching, it named Gaspar as one of only three in fine form. He finished the season with 19 wins and 11 losses, and a 2.01 earned-run average.

Sometime during that year, Gaspar’s father purchased an established photo studio in the Iowa town of Le Mars, the seat of Plymouth County. By that time Harry was married, and he and his wife, Coyla, began operating the business. Making Le Mars their home, they lived there for the remainder of Gaspar’s known ballplaying days.

The baseball season of 1910 proved nearly as successful for Gaspar as his first, with 15 wins and 17 losses, and an ERA of 2.59. The Le Mars Sentinel reprinted a unique Cincinnati Enquirer account of a game he won over the Giants in Cincinnati on August 20. Likening his pitching style to the artistic work of a great photographer, the article recorded that “It was a fine day for photographic work, and Mr. Gaspar … took speaking likenesses of all the Giant sluggers in various attitudes, mostly in the act of whiffing wildly at the curve ball.” Judging from that entry, Harry came to value that pitch after it got him into the majors. Earlier in the season, the Waterloo Daily Times Tribune quoted a Cincinnati Times-Star explanation for Gaspar’s success. It offered that he was neither wild nor strictly a control pitcher and that he “studied his batsmen the first time around the big circuit,” varying “things according to the gentleman facing him.” One thing’s for certain, Harry Gaspar maintained his composure at all times.

One story contended that when teammate Harry Coveleski (The Giant Killer) bragged about his own great control, Gaspar volunteered to participate in an experiment. He and Mike Konnick stood and leaned forward so that their heads were only a foot apart. Coveleski threw six times straight through the space between their heads, and into the waiting catcher’s glove. That might sound like overconfidence, but it also demonstrates Gaspar’s unflinching nerves. As for his throwing ability, during a Cincinnati field day in October, he tallied eight strikes out of 11 balls thrown, winning a competition.

By the time the 1911 season rolled around, Gaspar Studio in Le Mars had become a lucrative enterprise. Nonetheless, Harry couldn’t turn down a salary of $4,500 from the Reds. So in March he headed off to Hot Springs, Arkansas, for spring training while his wife manned the business at home. By June 18 a New York Times report of his 6-1 win over Brooklyn on the previous day called it “one of his best games of the season.” However, as the year unfolded, the Reds fell from fourth in 1909 to fifth in 1910 to sixth and below .500 in 1911. Although Gaspar still pitched skillfully, he wasn’t up to his usual capacity, and he didn’t get a lot of support from the team. He ended the season with an 11-17 record. His ERA of 3.30, though respectable, was telling when compared against those of his first two years.

When Gaspar signed with the Reds again in February 1912, the club had a new manager, Hank O’Day. In mid-February Gaspar said he intended to lease his business to another photographer for the season, as his wife, Coyla, would accompany him to Cincinnati. The Reds had raised his salary, and it soon became clear that an increase in income would be helpful to Gaspar. Because Coyla was ill, Harry and teammate Tommy Clarke spent two days in Norwood, Ohio, before rejoining the team on its way to a preseason game in Columbus. About two weeks later the news arrived in Le Mars that the Gaspars were now the parents of a baby boy. They named him Leo.

By June of that season, a prolonged future in the big leagues began to look doubtful for Harry Gaspar. It was obvious that he just wasn’t up to his usual standards; in four decisions, he captured only one win. That was on May 2 at St. Louis, where he shut out the Cardinals 10-0, allowing only four hits. News reports suggested that prolonged cool weather had taken a toll on his ability, but it is possible that his wife and new baby being with him may have been a distraction. Another factor that could have come into play was the new manager. That was O’Day’s first job managing a major-league club, and it lasted only one year. His second and last season as a manager was with the Cubs in 1914. In 1912 O’Day expressed disgust with the Cincinnati pitching staff, and in June he asked for waivers on Gaspar.

At first Brooklyn refused to surrender claim, but on June 21 Gaspar was released to Toronto of the International League. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported on June 22 that Gaspar was neither surprised nor distressed about the deal, but indicated that he would not report to Toronto. The story had many kind words for the Le Mars photographer. Of Reds fans, it said that “those who knew his courage and his sterling character” would be “sorry to see him go.”

Gaspar did go to Toronto, as evidenced by his 1912 record of 12 appearances with the Maple Leafs, registering four wins and three losses. An amusing article in the August 20 Atlantic (Iowa) News Telegraph related how Gaspar and a former Reds teammate held up a Maple Leafs game with Montreal. Harry and opposing pitcher Frank Smith gabbed for 17 minutes when Smith took his turn at bat. When the umpire got fed up and gave them one minute to resume play, there was cause for concern about which team to penalize if necessary. A number of news bits such as this suggested that Harry caught on well with the Canadian club, and that he was still the cool character he was from the beginning. However, at some point he was suspended for failure to report. For that reason, he spent the following year in Le Mars.

Most news items say that Harry failed to report to Cincinnati. Some say Toronto. It would seem more likely that it was the latter, either at the end of the 1912 season, or in the spring of 1913. Regardless, he agreed to manage and play for the Le Mars semipro team that year. He also pitched for several small-town amateur clubs during the summer months. On one July day in 1913, he pitched two games in as many Iowa towns, shutting out Pisgah 5-0 at Morehead in the morning and then traveling a hundred miles to a carnival in Oto, where he won an afternoon game for Danbury against Hornick, 8-6. By the end of September, word was out that Gaspar had purchased his release (from Cincinnati or Toronto) to gain reinstatement in Organized baseball. This created great excitement in northwestern Iowa, as the lifting of Gaspar’s suspension allowed him to take the mound for Le Mars in an exhibition game against the Sioux City Packers of the Western League. It soon became known that he intended to join that club for the coming season. At an October 8 awards banquet in his hometown, Harry received praise and $32.50 in gold for his major role in the success of the Le Mars baseball club in 1913.

Gaspar became the top pitcher of the 1914 Sioux City Indians, displaying the same prowess of his earlier years. His 25 wins and 7 losses pointed to a strong comeback. Local fans were ecstatic when on September 4 he pitched for the Le Mars club in an exhibition game with the Indians at Athletic Park in Le Mars.

As adroit with money as he was with a baseball, Gaspar did not jump at the chance to sign with the Indians again. A comical story in the March 9, 1915, Le Mars Sentinel demonstrates his bargaining acumen as well as his sense of humor. When asked if he’d received the contract in the mail, he responded yes, but suggested that something was missing – $50. Apparently, that tack got him the extra $50 in his contract. He did play for the Indians that year, chalking up a record of 19-11, the same as in his first year in a Cincinnati uniform. He also managed the Indians for part of that season, and for all of the next. Then the club moved to St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1917, representing both Sioux City and St. Joseph. Though no longer managing, Gaspar picked up a loyal following there. However, in June of 1918, he announced that he was retiring from professional baseball. After playing part of the season for St. Joseph, he decided that he needed to return to Le Mars, where his photo business required his attention. His last game with St. Joseph showed that it was not because of diminishing skill: With just 74 pitches and no walks, he shut out Joplin, 1-0.

Gaspar returned to Le Mars around the time his daughter, Jean, was born, which probably had something to do with his leaving St. Joseph. A newspaper article in 1918 (reprinted by the LeMars Globe-Post on July 19, 1923) indicated that Gaspar continued to draw interest from the majors even after his announced retirement. The article said that Gaspar “received a telegram from Manager Barrows of the Boston Red Sox, requesting Mr. Gaspar to wire terms as pitcher for the balance of the season.” Ed Barrow was looking to fill his pitching staff during the summer of a season when Boston won the World Series. But Gaspar passed up that opportunity, staying at home and turning his attention to his photo business and his growing family.

Although Gaspar never returned to professional baseball, he continued to play for semipro and amateur teams throughout northwest Iowa for the next few years. In 1921 he was the player-manager of the Le Mars club, drawing a salary of $1,000. When a local journalist suggested that businessmen who gave financial support to the team were questioning use of club funds, the usually unruffled Harry took umbrage, and signed with the Alton, Iowa, team for the following year. Finally, in 1923, he sold his studio, packed up his family and left Iowa for the warmer climate of Southern California.

Settling in Santa Ana, Gaspar co-owned and managed the Gaspar-Anderson Bowling Alleys there. Apparently the seasoned athlete could bowl as well as he could pitch. A news clipping he sent to a friend in Le Mars in 1924 said that he came within 21 pins of a perfect 300 game at least once that year. It is unknown whether or not he played baseball there, but he lived in California for the remainder of his life. After suffering from a heart ailment for some time, he died at his Santa Ana home on May 14, 1940. Survived by his wife, Coyla, and two children, Leo and Jean, he was buried at Holy Sepulcher Cemetery in Orange, California.

The Le Mars Sentinel on August 27, 1909, recorded what Gaspar said was the one thing he owed his success to. He said that before he pitched his first important game, his father took him aside and said, ” ‘Whatever you do, Harry, keep cool. Make the other fellows work for everything they get,’ ” and added, “I have been following dad’s advice ever since.” He never acquired a moniker as do many major-league players, but Cool Hand Harry could easily have sufficed.

Sources

“Alton Team Signs Up Gaspar,” LeMars (Iowa) Globe-Post, April 20, 1922, 1.

“Big Leaguers Here Today,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, September 4, 1914, 1.

“Box Scores,” Waterloo (Iowa) Evening Courier, June 13, 1912, 2.

“Brooklyn Beats Reds,” New York Times, July 31, 1911.

Dates – 1910s in Norwood, Ohio, rootsweb.ancestry.com, April 1 and 2, 1912.

“Death of Well Known Ball Player,” Hawarden (Iowa) Independent, May 23, 1940, 6.

“Famous Baseball Series Recalled,” Waterloo (Iowa) Evening Courier, October 30, 1911, 6.

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, Iowa, Plymouth County, Le Mars Township.

Gardini, Fausto. Luxembourg American Cultural Society Inc., GASPAR-Grosbous, Luxembourg.

“Gives Him Good Sendoff,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, June 11, 1918, 1.

“H. Gaspar Rolls High Score,” LeMars Globe-Post, November 17, 1924, 1.

“Harry Gaspar, Alton Pitcher,” Boyden (Iowa) Reporter, April 27, 1922, 1.

“Harry Gaspar, Former Major League Player, To Boss LeMars Team,” Waterloo Evening Courier and Reporter, April 15, 1921, 18.

“Harry Gaspar In Old-Time Form,” Waterloo Evening Courier, May 13, 1912, 2.

“Has Not Yet Signed,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, March 9, 1915, 1.

“Honor Ball Players,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, October 10, 1913, 1.

“Leave For The West,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, July 20, 1923, 1.

“Left For Hot Springs,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, March 7, 1911, 1.

“Manager O’Day was not in a pleasant humor…” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 14, 1912, 8.

“May Go To Toronto,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, June 25, 1912, 1.

“Necrology – Harry L. Gaspar,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1940, 2.

“Not Have Long To Wait,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, April 4, 1913, 1.

“Notes Of The Diamond,” Sheboygan (Wisconsin) Evening Press, August 28, 1912.

“Of Personal Interest,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, April 12, 1912.

“Off for Cincinnati,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, February 16, 1912, 1.

“One Blasted Cincinnati Hope,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1912.

“Packers To Come Here – Gaspar Buys Release And Is Reinstated,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, September 26, 1913, 1.

“Pitcher Does Daring Feat – Men Hold Heads Foot Apart While Sphere Shoots Between,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, April 24. 1910.

“Players Recall Old Times,” Atlantic (Iowa) News Telegraph, August 20, 1912, 8.

“Praise for Gaspar,” Waterloo Daily Courier, July 17, 1909, 2.

“Prospect For League,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, March 11, 1913, 1.

“Record For Ball Throwing Broken,” Canton Repository, October 10, 1910.

“Record With Pirates Proof Of Reds’ Class,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1909, 5.

“Reds Record In Series With Pirates,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1909, 5.

“Shy Of Twirlers,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1909, 4.

“Used Curve Ball But Once,” Oelwein (Iowa) Daily Register, October 2, 1914.

“Way Back When Waterloo Cubs Won League Flag,” Waterloo Evening Courier, September 12, 1927, 6.

“Will Be Here In Force,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, July 29, 1913, 1.

Works Cited

“Films Were Very Clear – Some Dope on Gaspar, the Reds Pitcher,” LeMars (Iowa) Semi-Weekly Sentinel, August 10, 1910, 1. col. 6.

“Gaspar In Form, Downs Brooklyn,” New York Times, June 18, 1911.

“Makes a Star Twirler,” LeMars Semi-Weekly Sentinel, August 27, 1909, 1.

” ’Member Way Back When –” LeMars Globe-Post, July 19, 1923, 1.

“Photographer Departs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 22, 1912, 8.

“Why Gaspar Wins Games At Cincinnati,” Waterloo Daily Times Tribune, June 12, 1910, 2.

Full Name

Harry Lambert Gaspar

Born

April 28, 1883 at Quorn, IA (USA)

Died

May 14, 1940 at Santa Ana, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.