Hilltop Park (New York)

This article was written by Bill Lamb

The cramped wooden ballpark had few admirers. Inconveniently located in the far northern reaches of Manhattan, it had been hastily erected in spring 1903 and was constantly in need of refurbishment. The team that it housed was a fitting occupant, a second-fiddle mediocrity that never won a pennant and only rarely contended for one. Unloved and short-lived – it served as a baseball venue for only ten years – scant tears were shed when the confines passed from the major-league scene after the 1912 season. Yet without Hilltop Park, the American League would have been unable to secure a foothold in New York City. And the fortunes of the game’s dominant franchise might well have played out far differently.

The cramped wooden ballpark had few admirers. Inconveniently located in the far northern reaches of Manhattan, it had been hastily erected in spring 1903 and was constantly in need of refurbishment. The team that it housed was a fitting occupant, a second-fiddle mediocrity that never won a pennant and only rarely contended for one. Unloved and short-lived – it served as a baseball venue for only ten years – scant tears were shed when the confines passed from the major-league scene after the 1912 season. Yet without Hilltop Park, the American League would have been unable to secure a foothold in New York City. And the fortunes of the game’s dominant franchise might well have played out far differently.

Hilltop Park was the end product of a clash between the two great executive forces in turn-of-the-century baseball. In one corner stood Ban Johnson, president of the fledgling American League and at peak form, having just wrung a peace agreement from his entrenched rival, the National League. In the other was New York Giants owner John T. Brush, the most influential magnate in the senior circuit and a longtime adversary of Johnson.1 Allied with Brush was Andrew Freedman, his predecessor as Giants owner and an important figure in New York City politics.2 Although officially divorced from the game,3 Freedman was agreeable to protecting Brush’s interests in baseball-related matters. And Brush was determined to maintain the Giants monopoly on major league baseball played in Gotham.4

Despite the bitter opposition of Brush (and Charles Ebbets of Brooklyn), the interleague peace parley of January 1903 had accorded official parity to Johnson’s American League. Johnson had also received license to place an AL club in New York, the nation’s largest city and its foremost sports market. With the Baltimore Orioles franchise in receivership and under league administration,5 Johnson had an American League operation at the ready for installation in New York. All that he needed were financial backers and a ballpark. But neither would prove easy to secure.

Although he had recently taken space in downtown Manhattan’s Flatiron Building, Midwesterner Johnson was largely unfamiliar with New York, particularly its political landscape. As he quickly discovered, deference had to be paid to Tammany Hall, the corrupt apparatus in control of the Democratic Party in the city. Fortunately for Johnson, Tammany was then in turmoil, its power weakened by citywide losses in the 1901 municipal elections and the ensuing fall of iron-fisted Wigwam boss Richard Croker. Among those reduced in rank by these events was Andrew Freedman, a Tammany insider closely connected to the now departed Croker. Unfortunately for Johnson, Freedman remained a Gotham power broker via his role as catalyst-in-chief for the Interborough Rapid Transit Corporation, the financial colossus directing the construction of New York City’s first true subway system. The IRT’s ability to encumber New York real estate for subway purposes was virtually unfettered and gave it effective control over wide swaths of territory, particularly in Manhattan. This, in turn, made Freedman, a millionaire who had made his first fortune as a New York City real estate operative and a Brush ally, a formidable obstacle to incursion into New York by the American League.

While the borough of Manhattan covers more than 22 square miles, it then contained only two major-league-caliber baseball parks: Polo Grounds III and Manhattan Field. Both of these were under the complete control of Brush,6 steadfast in his resolution to keep the American League out of New York, the provisions of the interleague peace agreement notwithstanding. With no prospect of obtaining accommodation from Brush regarding the use of his grounds, Johnson began the search for property suitable for ballpark construction. In time, he struck a deal with the IRT for acquisition of building lots located at uptown 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue. Or so Johnson thought. With the transfer about to be consummated, Johnson received a firsthand demonstration of Freedman clout. When the IRT board of directors met to ratify the deal, the transfer was abruptly quashed, the subway lords maintaining that they were not in the business of facilitating baseball ventures. Freedman publicly denied engineering the reversal, but the satisfaction that he so plainly took from events told a different story.7 Johnson interest in other properties, even in the outer boroughs, was likewise thwarted. Whenever Johnson had a line on stadium-suitable property, Freedman had the location attached for some putative subway purpose.

With the 1903 season on the horizon, Johnson’s would-be New York team remained homeless. This compelled him to pursue a distasteful course: seeking the aid of Freedman adversaries inside Tammany Hall. An old friend, sportswriter Joe Vila of the New York Sun, arranged for Johnson to meet Frank J. Farrell, New York City’s “Pool Room King”8 and an intimate of Big Tim Sullivan, a Tammany powerhouse more than the equal of Freedman. Farrell, a friend of Giants manager John McGraw and also co-owner of a New York racing stable, had been looking to expand his sporting interests into baseball. At the meeting he proffered Johnson a certified check for $25,000, a sort-of performance bond that the American League could retain as a forfeit if Farrell proved unable to get a team off the ground in New York. Impressed with Farrell’s confidence and enterprise, and with no other viable club sponsorship option, Johnson allotted his league’s orphan franchise to Farrell and silent partner Bill Devery, a former New York City police chief with an equally dubious pedigree. The franchise purchase price was only $18,000, it being understood that the real expense would arise from acquisition of a Manhattan ballpark site and the erection of a stadium.

To serve as the outward face of the new operation, genial coal merchant and former Manhattan state assemblyman Joseph Gordon was named club president.9 Among the attributes that Gordon brought to the endeavor was a thorough command of city geography; his business interests included a New York real-estate company. And until swept out of office in the anti-Tammany tide of November 1901, Gordon had served as deputy city commissioner of buildings. This familiarity with the local property market enabled Gordon to uncover a building site that had escaped the notice of Andrew Freedman: a rocky mesa in the far north Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights owned by the New York Institute for the Blind. Once a ten-year, $10,000-per-season leasehold on the property had been secured, the Greater New York Base Ball Club of the American League was ready for public unveiling.

At a press conference on March 12, 1903, Ban Johnson revealed the location of the new ballpark: West 165th Street and Broadway, or less than ten blocks from the Polo Grounds. While affording scenic views of the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades, a less hospitable site for a ballpark would have been difficult to imagine. As described in a doubtful New York Times report,

From Broadway looking west, the ground starts in a low swamp. It rises into a ridge of rocks perhaps twelve to fifteen feet above the level of Broadway. From the top of the ridge the land slopes off gradually to Fort Washington Road. As the property is today it will be necessary to blast all along the ridge, cutting off a slice eight feet or more. … There are about 100 trees to be pulled up by the roots.10

With Opening Day optimistically set for April 30, general contractor Thomas McAvoy, a former police inspector and the local Tammany district leader, loosed some 500 men on the site, with digging, dynamiting, and carting away debris continuing on a near around-the-clock basis. But midway through construction, the project was hit by labor troubles, with a considerable portion of the work force walking off the job until its demand for a $2-per-day wage was met. Brooking no construction delay, McAvoy promptly jettisoned the strikers, their ranks immediately filled by replacements desperate for employment. Work on the project continued apace.11 Then Andrew Freedman struck, orchestrating neighborhood opposition to the ballpark. Petitions submitted to the Washington Heights Board of Improvement maintained that residential property values would be diminished by the demimonde that the ballpark would spawn in the neighborhood. To forestall this threat, the petitioners wanted a city street cut through the ballpark site.12 But McAvoy proved more influential with the board than the Freedman surrogates. The petition was denied by a 3-2 vote.13 Meanwhile, progress continued at the site. Eventually 12,000 cubic yards of bedrock were excavated by the construction crew, replaced by some 30,000 cubic yards of fill. Once the trapezoid-shaped grounds were reasonably level, a crude diamond was laid out by future ballpark groundskeeper Phil Schenck. The initial playing field dimensions were oversized. The foul lines were a Dead Ball Era-distant 365 (left field) and 400 (right field) feet from home plate, with the fence in the right-center power alley a gargantuan 542 feet away.14

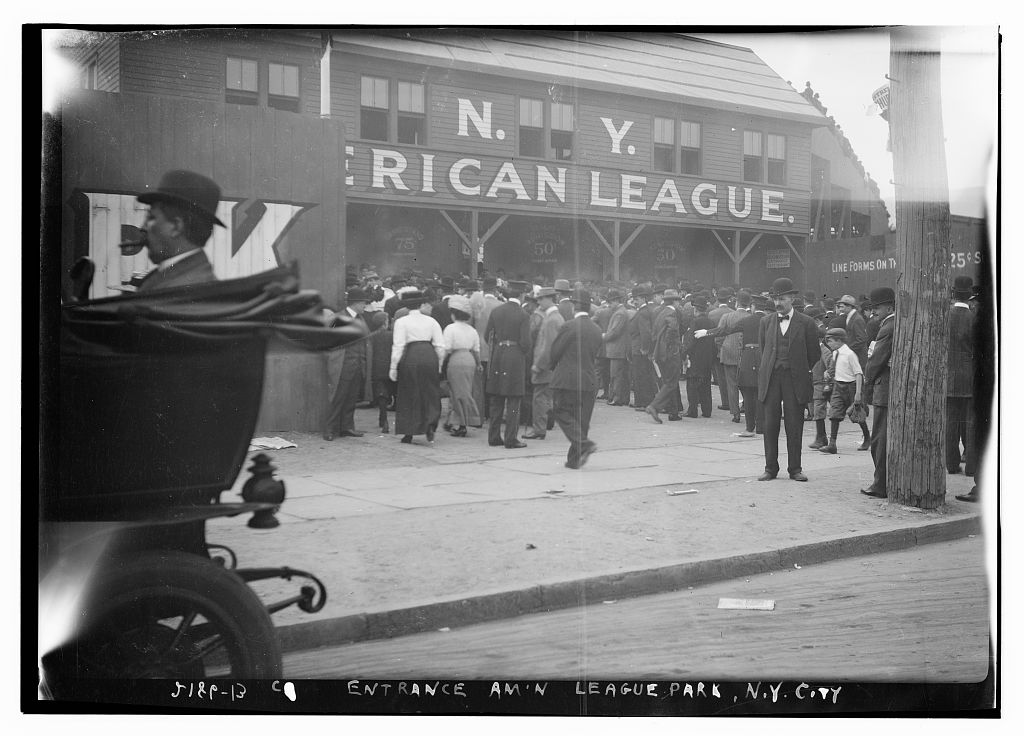

In a remarkable six weeks, the McAvoy construction crew had converted a picturesque but forbidding mesa into a serviceable, if unfinished, venue for major-league baseball. But the transformation had not come cheaply. The project had cost approximately $275,000 – $200,000 for clearance and leveling the site and $75,000 for construction of the ballpark – most of which would be borne by Farrell.15 The stadium structure was made almost entirely of wood. Fans would be accommodated in three grandstand sections ringing the home-plate area and extending along the baselines. Single-deck bleacher areas extended from the grandstands to the outfield fences while an adequately sized scoreboard was erected near the left-field foul line. The clubhouse was situated behind the center-field fence, while the main fan entrance was placed on the Broadway side of the ballpark.16

Officially titled American League Park of New York, the premises were commonly called Hilltop Park, a nod to the popularly-held but erroneous notion that the ballpark sat upon the highest point on Manhattan Island.17 The team that took the field for the April 30 New York home opener had been assembled by league president Johnson and was a competitive outfit. The roster featured future Hall of Famers Willie Keeler and Jack Chesbro and capable regulars like infielder Wid Conroy and lefty starter Jesse Tannehill. The club was guided by astute pitcher-manager Clark Griffith, also destined for Cooperstown. The substantial throng in attendance for the opener included silent team owners Farrell and Devery, seated prominently in a box near the Highlanders bench. Chesbro then hurled the home side to a 6-2 victory over the Washington Senators and New Yorkers left the park happy.

After a brief six-game homestand, New York went back out on the road. This permitted construction to resume on the ballpark. The grandstand roof had not yet been raised and the third-base-line bleachers needed attention. The playing surface was also a work in progress. The infield was bumpy and unreliable while little of the outfield grass seed had taken. Worse yet was right field, where a depression had necessitated the roping off of a sizable area in front of the fence and the employment of temporary ground rules during the opening homestand. Anything hit over Willie Keeler’s head had been an automatic double. When the team returned home, Hilltop Park had undergone significant renovation. The playing area had shrunk considerably, with the problem in right field cured by placement of the outfield fence in front of the depression, reducing the line to a mere 316 feet from home plate. The center-field fence was also brought in, now 17 feet closer than its original distance. Installation of additional bleachers behind the left-field fence increased the Hilltop Park seating capacity to approximately 16,000. With standing room, at times extended to the playing field itself, the ballpark could take in 25,000. But after Opening Day, expanded fan space was rarely needed. Despite a respectable (72-62) fourth-place finish, the Highlanders drew poorly in 1903. Season home attendance totaled only 211,808, a mere fraction of the 579,530 that the Giants had attracted to the neighborhood.18 The completion of the Highlanders’ maiden campaign, however, did not shutter the grounds. Like the Polo Grounds and Manhattan Field, Hilltop Park had the capacity to accommodate other sporting uses. That fall the park served as home field for the Manhattan College football team. In subsequent years, the grounds would play host to the Columbia (1904-1905) and Fordham (1908-1909) elevens.19

The Highlanders’ situation improved dramatically in 1904. The opening of a nearby West Side subway station made Hilltop Park much more accessible to the fans. The playing surface was much enhanced, particularly right field, where the depression had been filled in while the fences were restored to formidable dimensions (RF – 385/CF – 424/LF – 420). More important was the performance of the team. Behind a century-best 41 wins by Jack Chesbro, the Highlanders dueled Boston for the American League flag all season long. On October 10, 1904, an all-time-high Hilltop Park crowd of 28,584 swamped the park to see their heroes face the Pilgrims, only to see pennant hopes dashed by a late, game-losing Chesbro wild pitch. Although disappointed, New York partisans found some measure of consolation in the Highlanders’ strong (92-59) second-place finish. And club ownership was heartened by the patronage, the 438,919 paying customers more than doubling the previous season’s attendance. Unhappily, the club would not reach that attendance mark again during the next four campaigns, as the Highlanders mingled one good finish (second place in 1906) with three second-division ones.

The Highlanders hit bottom in 1908, their 51-103 log good for the cellar, 17 games behind seventh-place Washington. The scant crowds that made their way to Hilltop Park that season, however, were treated to some sterling mound performances – regrettably all by opposing pitchers. On June 30, 1908, the venerable Cy Young hurled his third career no-hitter in an 8-0 Boston triumph over New York. That September the Senators’ young Walter Johnson was perhaps even more dominant, shutting out New York three times in a four-day span (September 4 to 7, 1908). The Highlanders made progress in 1909, rising to fifth place and drawing more than 500,000 fans to Hilltop Park. That season also saw the famous Bull Durham tobacco advertisement mounted upon the right-center-field fence. But apart from that, the physical plant at the ballpark was headed in the wrong direction. The wooden superstructure was in almost constant need of repair and the seating capacity had become inadequate. Important contests regularly saw the players crowded by fans on-field at their elbow. Club ownership also detected early warning signs that the Institute for the Blind might not be amenable to renewing the lease to the grounds when the current ten-year pact expired. December 1909 reports that agents of Frank Farrell had acquired ballpark-suitable building lots in nearby Bronx were not, therefore, received with surprise.20

By the 1910 season, the once frosty relations between the two New York teams had thawed considerably. And as the Highlanders surged in the American League standings, holiday doubleheaders were sometimes switched to the more commodious Polo Grounds. At season’s end the second-place Highlanders (88-63) and the second-place Giants (91-63) finally agreed to a postseason series.21 Alternating between the Polo Grounds and Hilltop Park, the National League side prevailed four games to two (with one tie) behind yeoman pitching by Christy Mathewson (3 wins, 1 save). Despite constantly threatening weather, the games were a box-office success, drawing more than 100,000 fans. The series also cemented the cordial ties that had developed between the club front offices during the season.

The Giants would prove the immediate beneficiary of this good will. As the 1911 season was about to commence, the Polo Grounds was almost completely destroyed by fire. In response to this calamity, Farrell immediately placed Hilltop Park at the Giants’ disposal while the iconic Polo Grounds IV was being built. This accommodation was deeply appreciated by Brush and would redound to Highlanders benefit in the years to come. On April 15, 1911, the Giants opened a pennant-winning season playing at Hilltop Park and continued to play home games there until May 30. Meanwhile, the Highlanders, now under the field direction of the talented but troublemaking Hal Chase, regressed in both the standings (fifth place) and at the gate, down almost 200,000 patrons from the 1909 season. The slump in attendance at Hilltop Park had been suffered despite improvements to the grounds. A portion of the stands along the left-field line was now sun-shielded, and new center-field bleachers, also roof-covered, had been added. The latter installation necessitated reducing the straightaway center distance to a mere 370 feet from home plate, the shortest center-field dimension in the majors. But these were only stopgap measures. In the 1911 offseason, preliminary site work began on a new Highlanders ballpark, to be situated in the Bronx at 221st Street and Kingsbridge Road, hard by the Harlem River canal. Completion of this new venue was projected for June/July 1912.22

The 1912 season was a grim one for the New York Highlanders, by now more often called the Yankees. The ten-year lease on the Hilltop Park site was near to expiration and the Institute for the Blind, envisioning more lucrative use of the property, was disinclined to renew, even on a short-term basis. Unfortunately for the club, the Kingsbridge Road project was beset by problems, the most consequential of which was chronic inability to stanch the flow of the neighboring Spuyten Divil Creek. This often placed the work site under water, bringing construction to a halt. New York fortunes fared no better on the diamond, with new manager Harry Wolverton steering the club to a dismal 50-102 record, some 55 games behind the pennant-winning Boston Red Sox. The season was also marred by an ugly grandstand incident. On May 15, 1912, the Tigers’ Ty Cobb responded to probably obscene heckling by a Hilltop Park patron, scaling the fence and delivering a severe beating to his tormentor, who turned out to be handicapped. This conduct earned Cobb suspension by American League president Johnson, which in turn prompted a famous walkout by Detroit players in support of Cobb.23 Meanwhile, the New York season trudged to its conclusion. On October 15, 1912, baseball at Hilltop Park ended much as it began, the home club inflicting an 8-6 defeat upon Washington, the Opening Day victim of the 1903 season. With that, the ten-year tenure of Hilltop Park as a major-league baseball park came to a close. Four days later, a Rhode Island-versus-Fordham football game marked the passing of the grounds from the sporting scene for all purposes.24

For the 1913 season and for the nine that followed, the New York Yankees would play their home games at the Polo Grounds, a more than ample repayment by Giants owners for the assistance rendered them by Frank Farrell in early 1911. When the tenancy began, work at the Kingsbridge Road site continued but construction problems were never overcome. By the time the project was abandoned, the boondoggle had cost Farrell a fortune, seriously undermining his ability to retain control of the franchise.25 Meanwhile, Hilltop Park remained quiet. In 1914 the ballpark was demolished, clearing the site for more profitable investment prospects that were slow to materialize. The property was reportedly sold in June 1916 for some $2.5 million but the identity of the purchaser and other details of the transaction were not immediately disclosed.26 Thereafter, the site remained vacant until construction of a hospital building began in 1928. Later, the sprawling Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center assumed the grounds.

In September 1993 a small five-sided plaque was placed within the medical center confines. The inscription reads, “Dedicated to Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center and the community of Washington Heights by the New York Yankees to mark the exact location of home plate in Hilltop Park, home field of the New York Highlanders from 1903 to 1912, renamed the New York Yankees.”27 Today, this modest memorial provides a rare tangible reminder of the unloved and short-lived ballpark that served such a vital purpose during the baseball turf war of a bygone age.

NOTES

1 The enmity between the two men dated from the early 1890s, when Brush’s tenure as principal owner of the Cincinnati Reds was regularly lambasted by young sportswriter Ban Johnson of the Cincinnati Commercial-Gazette. Thereafter, the two continued to butt heads when Johnson assumed the presidency of the Western League, whose dominant Indianapolis team was owned by Brush.

2 Long a minority stockholder in the Giants franchise, Brush had acquired control of the team in September 1902, his purchase of Freedman’s controlling interest in the New York club financed by the sale of the Reds to well-heeled Cincinnati politicos.

3 Although he had retained a nominal number of shares in the National Exhibition Company (the Giants corporate alter ego), Freedman had declined a seat on the franchise board of directors and took no active role in club affairs, apart from making things difficult in New York for would-be Giants competitors.

4 The New York Metropolitans of the American Association, the last major-league team to share Manhattan with the Giants, had relocated to Staten Island in 1886 and disbanded two seasons later.

5 During the 1902 season, a cabal masterminded by Brush had briefly placed title to the AL Baltimore Orioles in Freedman’s hands. But within days, a Baltimore forfeit (for failure to put a team on the field for a game against St. Louis) allowed Johnson to strip the team from Freedman and place the Baltimore franchise under administration by the American League. For more on these events, see W.F. Lamb, “A Fearsome Collaboration: The Alliance of Andrew Freedman and John T. Brush,” Base Ball, A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Fall 2009), 14-15.

6 The Polo Grounds and Manhattan Field were situated side-by-side in northern Manhattan. The stadiums themselves were among the assets acquired by Brush when he bought the Giants franchise. The ground on which the ballparks sat, however, was not his. Rather, the property was the subject of long-term lease agreements that Giants owners had reached with John J. Coogan, estate agent for the vastly propertied Gardiner-Lynch family, the titleholders of the real estate.

7 Shedding crocodile tears, Andrew Freedman observed that “Someone has been stringing these Western men (along) and it is time it was stopped. It is simply brutal.” For a more detailed account of the machinations that quashed the sale, see Glenn Stout, Yankees Century: 100 Years of New York Yankees Baseball (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 9-10.

8 The moniker derived from Farrell’s control of off-track betting parlors, a rewarding if unlawful enterprise in turn-of-the-century New York City.

9 Gordon was a well known figure on the local sports scene, having previously served as president of the New York Mets and as a corporate board director of the New York Giants.

10 New York Times, March 14, 1903.

11 Club president Gordon was miffed by the walkout, advising the press that the $1.50 per day paid site workers exceeded the prevailing $1.25-per-day rate and that the men had to work only nine hours instead of the standard ten. “In the case of these laborers we offered better terms and shorter hours because we want good, reliable men to push along the work to speedy completion, and there will be no delay, as we have got plenty of men,” said Gordon. New York Times, March 31, 1903.

12 Such neighborhood petitions were matters that New York baseball club owners viewed ominously. The original Polo Grounds at 110th Street and Central Park North had been razed in 1889 to placate a similar resident demand for completion of the local traffic grid.

13 New York Times, April 10, 1903 (which misreports the vote as 4-3).

14 The primary source of Hilltop Park dimensions is Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 3rd ed., 2006).

15 Yankees historian Stout surmises that Farrell received some degree of reimbursement for construction expenses from the American League.

16 For Hilltop Park photos displaying these features, see Vincent Luisi, New York Yankees: The First 25 Years (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2002).

17 The highest elevation in Manhattan is actually located in nearby Hudson Heights. The informal Highlanders nickname is often attributed to the lofty site of the New York ballpark. Other times it is said to be grounded in the surname of the club president, a play on the Gordon Highlanders, a crack Scottish regiment.

18 Attendance figures are taken from Total Baseball, 7th ed., John Thorn et al, eds. (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 75. The 1903 Highlanders also drew only half the fans of their nearest American League competitor, Philadelphia (422, 473).

19 For a complete accounting of the college football games played at Hilltop Park, access http://www.luckyshow.org/football/hp.htm.

20 Such reports appeared in both news and real estate articles published in the New York Times, December 25, 1909.

21 In 1904 Giants owner Brush had refused to play any “minor league” opposition for baseball’s championship, a move widely viewed as a deliberate snub of the Highlanders, prospective American League pennant winners. Two years later, Brush was a changed man, heartily endorsing a postseason series between the two New York clubs. But Highlanders boss Frank Farrell, giving Brush “a dose of his own medicine,” vetoed the match. See the Washington Post, October 4, 1906. For several years thereafter, the idea of postseason intracity play in New York was a nonstarter.

22 New York Times, November 12, 1911. A more guarded “some time before the close of the (1912) season” was offered in “Why I Am Building a New Park,” by Frank J. Farrell, President, New York Americans Baseball Club, Leslie’s Weekly, April 4, 1912.

23 For more on the incident and its aftermath, see Charles C. Alexander, Ty Cobb (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 105-107.

24 The battle of the Rams ended with a 6-0 Rhode Island victory.

25 Farrell and Devery also suffered other financial reverses. In January 1915 the pair sold the franchise for a reported $460,000 to Jacob Ruppert and Til Huston, the owners who would place the Yankees on the path to glory.

26 For limited details, see the New York Times, June 24 and 27, 1916.

27 The commemorative Hilltop Park plaque is depicted in Luisi, 54.