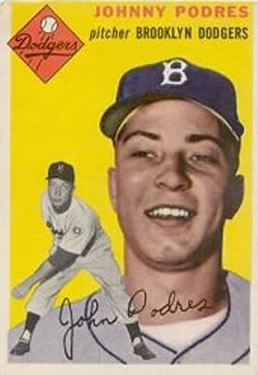

Johnny Podres

Outside the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, a statue depicting southpaw Johnny Podres after a pitch release stands 60 feet, six inches from a statue of catcher Roy Campanella. They commemorate the Brooklyn Dodgers winning the 1955 World Series over the New York Yankees, their traditional autumn foe at the time.

Outside the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, a statue depicting southpaw Johnny Podres after a pitch release stands 60 feet, six inches from a statue of catcher Roy Campanella. They commemorate the Brooklyn Dodgers winning the 1955 World Series over the New York Yankees, their traditional autumn foe at the time.

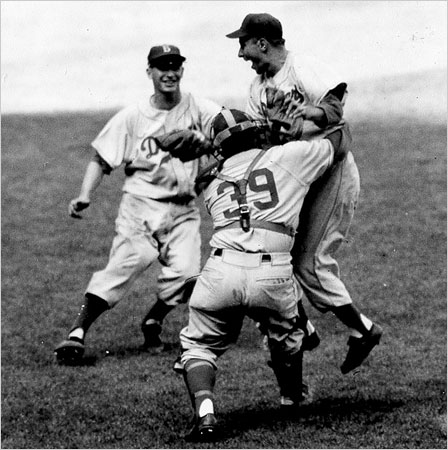

On October 4, 1955, Podres pitched a complete-game 2-0 masterpiece in Game 7, Sandy Amoros made an epic catch to save the Dodgers from a Yankee rally, and Brooklyn’s ballplayers ascended from knights to kings.

The Brooklyn Dodgers seemed destined for permanent bridesmaid status until their 1955 victory vanquished the ghosts of postseasons past — World Series defeats in 1916, 1920, 1941, 1947, 1949, 1952, and 1953.1

A native of the Adirondacks, John Joseph Podres was born on September 30, 1932 in Witherbee — one of five hamlets in Moriah, New York — about 160 miles from those two statues in Cooperstown. Moriah, which also encompasses the Village of Port Henry, is a 73-square mile outdoorsman’s paradise with abundant hunting and fishing opportunities. No one was a greater patron than Podres, whose grandfather, Barney, an immigrant from Russia, settled in the Adirondacks. Barney Podres married twice — the first time to a woman of Lithuanian heritage — and worked in upstate New York’s mines for nearly 50 years.2 When the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame inducted him in 2002, Podres explained his heritage: “A lot of people don’t even know I’m Polish. They think I’m Spanish, but I’m Polish and Lithuanian. This is quite an honor and I’m proud to be part of an organization that has so many distinguished athletes.”3

Also a miner, Podres’s father, Joe, found an outlet on Sundays, playing semi-pro baseball for 25 years.4 Podres’s mother, Anna (née Glebus), worked at the Moriah Central School cafeteria.5

“When he was a little boy, he used to listen to the Dodger games on the radio in his room. His mother would say, ‘Turn that radio off. You have school tomorrow,’” explains his widow, Joan.6

Podres had three brothers — Thomas, Walter, and James — and a sister named Mary. An uncle, who was also a high-school teammate, combined with the future Dodgers hero in a nail-biting 1-0, 17-inning game to win the 1949 Southern Essex County League title for Witherbee’s Mineville High School.7

Podres pitched for the Burlington (Vermont) Cardinals of the Summer Collegiate Northern League in 1950, after graduating from Mineville High.8 In 1951, he notched an 0-2 record in seven games for the Class D Piedmont League’s Newport News (Virginia) Dodgers before joining the Hazard (Kentucky) Bombers in the Mountain States League. There, he compiled these numbers:

- 1.67 ERA

- 21-3 win-loss record

- 228 strikeouts (led the league)

“Max Macon worked on my curve a lot,” stated Podres of the Bombers’ manager, a journeyman minor league skipper who spent most of his career managing in the Dodgers organization.9 Podres’s excellence began on May 20th, in a 15-7 victory against the Big Stone Gap Rebels. In its recounting, the Hazard Herald misspelled his name as “Padres.”10 Not until Podres’s fourth game, a two-hitter, did it rectify its error.11

Hazard went on to win the 1951 Mountain States League title against the Morristown Red Sox.

Podres’s transition to the Old South was, perhaps, an easy one for the Adirondacks-born pitcher, who was familiar with living in an isolated region. Remoteness in coal country did not make Hazard a backwards microcosm of society, though — quite the opposite, in fact. “As bankers and attorneys and doctors came in, many of these professional people believed their town could be a beacon of civilization in the Appalachians and they set about raising their children to maintain it as such, by providing them with concerts and dance lessons and excellent educations,” wrote historian L.M. Sutter in her 2009 book Ball, Bat and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South.12

Brooklynites turning to page six of the Brooklyn Eagle on February 9, 1952, found an item about Don Newcombe’s impending military duty prompting the need to shore up the Dodgers’ pitching staff. It also highlighted Podres — the only lefthander in a group of minor league prospects — as having “a good fast ball and curve.”13 Dodgers skipper Chuck Dressen noted, “He’s the best looking pitching prospect I’ve seen in years.”14

Podres’s first performance for the Dodgers came in an intra-squad game in spring training. It resulted in three innings, no walks, three hits, five strikeouts, and a final score of 9-1 for Podres’s team.15 A pulled back muscle delayed his first appearance against major leaguers.16 However, Podres got the nod for the March 9th preseason contest against the Boston Braves. Here, he did not fare quite as well as in the intra-squad game — 9,673 witnesses saw the Dodgers fall to the Braves 6-2; the kid from Witherbee gave up two runs, both unearned, in his three innings on the mound.17 But his performance steadily improved, garnering praise from Harold Rosenthal of the New York Herald Tribune: “[I]n the short space of three weeks he has now moved from the point where he had to make the team to where any of the non-regulars must elbow him out of the way — if they are able.”18

Dodgers General Manager Buzzie Bavasi reportedly ignored a tempting $250,000 offer for Podres from the Cleveland Indians during spring training. Bavasi, according to the story, rejected the offer, despite a 1-A draft classification that made military service for Podres, and a probable stint of two years if it materialized, a distinct possibility.19 Or at least that’s what the Eagle reported on March 21st — and then debunked on March 22nd, calling it a “wild yarn” and quoting Bavasi’s telegram to Indians General Manager Hank Greenberg: “If this story is true, send on check immediately.”20

Determining that Podres was not quite ready for the majors, Dressen sent him to the Dodgers’ AAA team — the Montreal Royals in the International League — along with pitcher Mal Mallette, whose major league career had consisted of two games and 1 1/3 innings pitched for the Dodgers in 1950.

Podres went 5-5 for the Royals, a team boasting several future major league players; pitcher Tommy Lasorda had an impressive 14-5 record for Montreal in 1952, but a 0-0 record for the Dodgers in 1954 and 1955 — his only two years in the big leagues. It was Lasorda — spelled “LaSorda” in the Montreal Gazette — who preserved Podres’s first Montreal win, along with Jim Hughes. Manager Walter Alston, who became the Dodgers’ manager in 1954, sent Podres to the clubhouse in the eighth inning with a 6-4 lead after the hurler gave up a walk and a single. The final score was 6-5, Royals over the Syracuse Chiefs.21

In 1953, Podres again seemed a likely major league prospect. “He has looked the best of the young pitchers,”22 declared Dressen. Jim (“Junior”) Gilliam and another pitcher, Bob Milliken, joined Podres on the Brooklyn squad.23 Podres threw seven innings and let only four pinstriped players get on base in a 9-0 victory in the 1953 Mayor’s Trophy Game against the Yankees; his effort benefited from Wayne Belardi’s two homers, double, and six RBI.24

Though not overpowering — his ERA was 4.23 — Podres went 9-4 in his rookie season, started 18 games, completed three, and pitched 15 times in relief. He was, in no small part, a factor in the Dodgers repeating as National League champions.

However, their bid for a World Series title ended, yet again, in a loss to the Yankees. Podres started Game 5, which the Yankees won in an 11-7 contest that included a two-out grand slam by Mickey Mantle off Russ Meyer, who had relieved Podres, in the third inning. Dressen later explained why he pulled the southpaw for the right-handed Meyer. “I had to turn Mantle over. He can kill you batting right-handed but we have been getting him out left-handed because he has that bad right knee and can’t pivot. So we send in the right-hander and curve him inside where he can’t take a good cut — see.”25

Things didn’t go exactly according to Dressen’s plan.

Podres returned in 1954, carving out a sophomore season just as impressive as his first. He won 11 and lost 7, while completing six of his 21 starts and throwing two shutouts.

A 9-10 record in 1955 belied Podres’s excellence on the mound in that year’s World Series. Alston first gave the ball to Podres for Game 3; the Dodgers won 8-3.

“He had the kind of equipment that was good for the Yankees,” said teammate Clem Labine. “He had a great change-up. But what I worried about with him was [Mickey] Mantle ’cause Mantle liked lefthanders.”26

An injured Mantle did not appear in the starting lineup for Game 7 — a blessing for Brooklyn; the “Commerce Comet” pinch hit in the 7th inning and popped out. Plagued by knee problems, Mantle sat out Game 1 and Game 2 — the Yankees won both. Brooklyn evened the score with Game 3 and Game 4 victories. The rivals split the next two games, which Mantle also saw from the bench.

Podres went the full nine in Game 7, crediting Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella with the 2-0 victory: “Campanella was calling the greatest game of his career. Every time he’d give me a sign, ‘I want you to throw it here,’ I was throwing it there. ‘I want it up and in.’ I’d throw it up and in. ‘I want it low and away.’ I’d throw it low and away. ‘Curve ball in the dirt.’ I put it in the dirt.”27

Podres went the full nine in Game 7, crediting Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella with the 2-0 victory: “Campanella was calling the greatest game of his career. Every time he’d give me a sign, ‘I want you to throw it here,’ I was throwing it there. ‘I want it up and in.’ I’d throw it up and in. ‘I want it low and away.’ I’d throw it low and away. ‘Curve ball in the dirt.’ I put it in the dirt.”27

In the bottom of the sixth inning, left fielder Sandy Amoros saved the Dodgers. With Gil McDougald on first base, Podres faced the famed Yankee catcher — “I had Yogi Berra, two strikes. I threw him a fastball had to be nine, ten inches outside. Wasn’t even close to being a strike. A little pop fly to left. But it was a slice,” recalled Podres. 28

Left fielder Amoros, positioned so close to center field that a gallop or two would have lined him up behind second base, raced toward the foul line like he had rockets on his cleats, made a one-handed catch, and fired the ball to shortstop Pee Wee Reese, who relayed it to Gil Hodges to double up McDougald. It was a vital play. McDougald had already rounded second by the time Amoros caught the ball. If Amoros hadn’t made the spectacular catch, then it’s very likely that McDougald would have scored, Berra would have trotted into second base with a double, and Podres would have faced Hank Bauer, who would hit .429 in the Series.

When Podres returned home, Witherbee honored him with a parade, attracting approximately 3,000 people.29

Though the military turned Podres away in 1952, it put him through examinations.30 Now, three days after Christmas 1955, Podres got his classification — 1-A. “If grief hangs like a heavy pall over the land stretching from Greenpoint to Canarsie, there may also be sighs of relief that reach all the way to St. Louis,” wrote Arthur Daley in the New York Times.31 The Dodgers front office showed its loyalty through greenbacks, signing Podres for a $15,000 salary — 20% over his 1955 salary, despite the possibility of Podres being sidelined for 1956.

Which is exactly what happened — Podres became a sailor in the United States Navy.32 Yet serving his country did not, in any way, diminish his baseball skills — he pitched for Bainbridge Naval Station and Glenview Air Station.33 The Navy released Podres in October because his back issues made him “physically unfit for further military service.” It was “a form of arthritis of the spinal column.”34

Returning to the Dodgers in 1957 — the last year for the team in Brooklyn — Podres got a salary bump to $18,000. 35 He began the season with nine strikeouts in a 2-0 victory against the Pirates36 and ended it with a 2.66 ERA and six shutouts, leading the majors in both categories. “He was in the best physical condition in his life coming out of the Navy,” explained Pat Salerno, Jr. and Pat Salerno, Sr., who were close friends with Podres and fellow outdoorsmen, sharing his passion for hunting and fishing. 37 The younger Salerno designed a road sign emphasizing Port Henry as the home of Johnny Podres.

Podres signed with the Dodgers again in 1958, for $17,000.38 Their new home, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, was a Goliath compared to the intimacy of Ebbets Field, which seated approximately 32,000 and occupied one city block. More than 78,000 saw the first regular season Dodgers home game, a 6-5 victory over the rival Giants; owner Horace Stoneham had followed Walter O’Malley’s template of transplant and moved the Giants to San Francisco, so enmity between the two squads continued in California.

Podres inaugurated night baseball for Major League Baseball’s new L.A. team on April 22, allowing four hits in a 4-2 victory. The only Chicago Cub runs off him came from a two-run homer by Ernie Banks. He added another victory of distinction when he threw a three-hitter against the Reds for the first shutout in the Coliseum, which could be a nightmare for a left-handed pitcher facing right-handed batters — 250 feet down the left field line and 320 feet to the left-center fence. A 40-foot high screen stretching from the foul pole to the center field fence alleviated some of the pressure on southpaws.

Although Podres ended the season with a less-than- spectacular 13-15 record, he predicted that he would be a 20-game winner for 1959. “I blew 1-run leads in the eighth or ninth innings at least three times, so I should have finished with a 16-12 record instead of 13-15,” claimed Podres. “But it was my own fault. As you know, I won only two games on the road and 11 in the Coliseum. I’ve thought about it a lot, and I think the reason for this screwy showing because I pitched more carefully in the Coliseum.”39 With a distance of 250 feet from home plate to the left field fence, Podres had good reason for the “more carefully” approach. It was a ballpark characteristic that warranted absolute control for lefties facing right-handed hitters.

Podres lost the Dodgers’ home opener in 1959, but got back on track for his next start — an 8-3 four-hit win over the Cubs.40 A month later, Podres shut out the Giants 8-0 in a two-hitter at Seals Stadium. Another two-hitter followed on June 11th against the Phillies, with no Philadelphia player getting to second base; Dodger bats amassed 11 runs in the shutout. In September, Podres notched 14 strikeouts in a 7-1 drubbing of the Cubs.41

The Dodgers went 88-68 in 1959, captured the National League pennant, and defeated the Chicago “Go Go” White Sox in the World Series. Podres contributed 14 wins and 9 losses to the regular season tally and one win in the World Series.

Entering 1960, Podres marked 20 wins as a goal, neither a promise nor a prediction.42 The Dodgers raised his salary to $22,000.43 Podres finished 1960 at 14-12, returning in 1961 with an 18-5 record to lead the National League in winning percentage (.783). Podres’s 18th and final win — and 100th career victory — happened on September 3rd, against the rival Giants.

Podres was rewarded for his 1961 performance with a salary increase to $28,500 in 1962.44 He inaugurated Dodger Stadium; however, the Reds beat the Dodgers 6-3 thanks to a three-run blast by Reds outfielder Wally Post and Vada Pinson’s 4-for-4 performance at the plate. Alston gave the ball to Larry Sherry in the eighth inning after the Reds pounded Podres for 11 hits.

On May 18th, hearts of Dodger fans dropped when a Ken Boyer ground ball hit Podres in the elbow of his pitching arm during the first inning of a Cardinals-Dodgers game at Dodger Stadium; the Cardinals won 8-3.45 Fortunately, it sidelined the southpaw only for the game. He returned on May 24th to pitch against the Mets. After leaving the game for pinch-hitter Wally Moon, Podres got a no-decision; Sherry got the win. Final score: 4-2.46

Podres started the All-Star Game for the National League in 1962, a memorable year for the Dodgers. Tied for first place with the Giants at the end of the season, the Dodgers entered a three-game playoff. Memories and ghosts of 1951 haunted the thoughts, hearts, and souls of Dodger fans everywhere — decades later, Brooklynites who remember the moment still cringe at the mention of Bobby Thomson or the sound of radio announcer Russ Hodges bellowing “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!”

The Dodgers lost the ’62 pennant to the Giants in a playoff, but it was still a remarkable year:

- 102-63 win-loss record

- Maury Wills leading the major leagues with 104 stolen bases and winning the National League MVP Award

- Don Drysdale’s 25-9 win-loss record and Cy Young Award

- Tommy Davis leading the major leagues with a .346 batting average, 153 RBIs, and 230 hits

Podres went 15-13 in 1962. While it may seem to be a falloff from his outstanding year in 1961, a win-loss record is not solely determinative of success. Podres had nearly identical ERA numbers in both years: 3.74 and 3.81. Further, his stamina improved, culminating in a career-high 255 innings and a 38 percent increase in games started: 29 in 1961, 40 in 1962. He got a salary bump for 1963 — $35,000.47

A 7-0 victory against the Reds on April 24, 1963, was a doozy — a total of five balks, three by Reds pitcher Jim Owens in the second inning, a National League record. The Cincinnati dugout emptied like the bench was on fire. Arguments led to an ejection of Owens, whose reliever John Tsitouris allowed a run when he balked in the seventh. Podres was not without sin — he balked once. The Dodger bats accumulated seven runs while Podres allowed none for the Queen City boys for the 18th shutout of his career.48 His second shutout of the season came on May 16th against the Pirates, a 1-0 contest that John Roseboro won by singling home Jim Gilliam.49

Podres hurled a two-hitter against Cincinnati on July 5th; Frank Howard tattooed a ball in the seventh inning, a solo home run to give Podres the 1-0 victory. Podres had fielding help, too — a “leaping catch by Tommy Davis against the leftfield boards” and Moose Skowron’s “nifty fingertip catch of pitcher [Jim] O’Toole’s foul bunt.” It brought Podres’s record to 6-6.50

A 6-0 shutout against the Pirates on July 22nd was Podres’s fifth for the year, though it was not, by any means, an easy journey. “A 6-0 shutout sounds like a breeze, yet Podres (10-6) put men aboard in every inning except the fourth, and but for some brilliant defensive play by Maury Wills, who started three crushing double plays, it might have been a different story,” wrote Frank Finch of the Los Angeles Times.51

On August 4th, a no-hit bid fell short when the Houston Colt .45s second baseman, Johnny Temple, led off the bottom of the ninth with a single and Podres hit Bob Aspromonte with a pitch. To that point, Podres had allowed only three walks. Sherry put out any embers to secure the victory for Podres. Sandy Koufax had silenced Houston’s lineup with a three-hitter the previous day.52

The Phillies knocked the Dodgers around for a 12-3 beating in Podres’s last start of the season on September 28th. He didn’t last long — 12 hits, 8 runs, 1 2/3 innings. Podres ended 1963 with a 14-12 record.

Up one game against the Yankees in the World Series, the Dodgers sent Podres to the mound for Game 2, where he performed brilliantly in a 4-1 victory. Podres admitted that he was tired when Alston pulled him out of a potential shutout in the ninth inning. Podres’s selflessness manifested in highlighting relief hurler Ron Perranoski, who led the National League in games (69) and the major leagues in win-loss percentage (16-3, .842). “Sure, I’d like another shutout but there’s no sense fooling myself when we’ve got the greatest relief pitcher in baseball.”53

The Dodgers won the next two to sweep the Yankees.

For 1964, the Dodgers paid Podres $35,000.54 A strained left elbow sidelined him in mid-April.55 Podres’s first appearance of the ’64 season came on April 25th in a Braves-Dodgers game, when Warren Spahn fired a ball that found its way to Podres’s elbow. Although X-rays were negative, the injury was severe enough to keep Podres on the bench. It was “in the same spot. The joint was considerably swollen.”56

In early May, the Dodgers tried to send Podres packing to Houston in a trade, but it fell through.57 By the middle of the month, Podres still hadn’t gotten a green light from Alston to take the mound. He did throw batting practice on May 11th but suffered for it on a pitch to Wally Moon. Podres explained that he sensed “something pop” in the weakened elbow.58

The elbow injury began, according to Dodgers physician Dr. Robert Kerlan, as a childhood injury that got aggravated.59 Podres disagreed: “This is like nothing I’ve ever had before.”60 He also revealed the extent of the pain. “Right now, it feels fine. But when I grip a baseball and try to throw, it feels like 100 hot needles jabbing my elbow,” explained the hurler.61 Of course, this would only have been known to Podres if he had violated the doctor’s mandate of complete rest, which he admitted.62

Podres underwent an operation on his elbow.63 He tried to work out in August, but Dr. Kerlan advised him to stop after the elbow swelled.64

In the fall, Podres pitched in the Arizona Instructional League, which provides a tutoring atmosphere for major league prospects and an opportunity for veteran players to improve or develop their skills. “My arm feels great,” declared the lefty. “I’ve never been able to throw harder than I’m throwing now,” wrote Podres to the doctor. “The arm is going to be stronger than it ever was.”65

Podres’s elbow wasn’t the only thing subject to the knife — the Dodgers sliced his 1965 pay by “a cut and a half,” stated the southpaw.66 He started 22 games that year and went 7-6 with a 3.43 ERA.

Before the 1966 season began, Podres married Joan Taylor, an Ice Follies skater. On the diamond, the upcoming season beckoned with promise because Podres added a new pitch to his repertoire — the slider.67 Podres played in one game for the Dodgers, but on May 9, 1966, his time in a Dodgers uniform ended with a trade to the Detroit Tigers, who paid the waiver price — $20,000 — and agreed to send a player to be named later. Podres had an abundance of choices in the American League; Detroit’s skipper proved to be the deciding factor. “When the Dodgers decided to trade John, they gave him a choice — Detroit or Boston. He chose Detroit because Chuck Dressen managed the Tigers and he knew Chuck from their days together in Brooklyn,”68 explains his widow, Joan. Buzzie Bavasi, in a stroke of loyalty, honored Podres’s selection. “We figured we owed him at least that much,” said Bavasi.69 Dressen passed away before the season ended.

Podres went 4-5 with the Tigers in 1966 and 3-1 in 1967. He was a swingman for the Detroit squad, which let Podres go before the 1968 season. Podres reached out to former Dodgers teammate Gil Hodges, who had just taken the helm of the New York Mets. It was to no avail — Hodges wanted younger players.70 The Dodgers presented an opportunity to be a pitching coach at their AAA team, the Spokane Indians of the Pacific Coast League.71 This never came to pass; Podres likely turned it down.

At age 36, Podres made a comeback with the San Diego Padres during the expansion year of 1969, his last year in a major league uniform. Podres ended his career with a 5-6 season.

Because of the iconic exploits of Koufax and Drysdale, Podres’s career gets overshadowed in Dodgers lore, scholarship, and history. It should not be so:

- 148-116 win-loss record, for a .561 winning percentage

- 3.68 ERA

- 2,265 innings pitched

- 24 shutouts

- 1,435 strikeouts

- Four World Series rings

Podres notched 136 wins as a Dodger, which as of 2017, still places him in the top 10 in franchise history.

After his playing days, Podres became a pitching coach with the Padres, Red Sox, Twins, and Phillies. His tutoring spanned more than 20 years, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s.

“He knew how to talk to pitchers,” says Joan Podres. “He showed them that they could have the confidence to go out there and perform. He knew what pitchers go through, pitching every four games and being on your game plan. There comes a point when you have to think about what happens when you’re not getting it over the plate, and that’s when the coaching came in. Two of the pitchers he coached were Curt Schilling and Tommy Greene.”

“I think that he thought that he was a diamond in the rough from a small town and he wanted to be remembered as showing that someone from a small town can succeed at the major league level. It was his calling. You never had a long game when John pitched because he pitched fast. He said that Roberto Clemente was the toughest hitter he ever faced.” The Pirates star got the first hit of his career against Podres. It was an infield single.72

Never losing his passion for a quieter life, Podres returned to the rural region that propelled the beginning of his baseball journey. He and Joni raised two sons — John, Jr. and Joseph. Podres died in 2008 after battling a leg infection, in addition to heart and kidney issues.73

Two reminders honor Podres: Johnny Podres Field at Moriah Central High School — a result of Mineville, Port Henry, and Moriah combining their high schools in the late 1960s — and the road sign on the shores of Lake Champlain in Port Henry, underscoring Moriah as the lefthander’s hometown.

It was, perhaps, destiny that brought the Adirondacks native — who followed the Dodgers as a kid — to baseball’s biggest stage, where he became a savior to Brooklyn.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joe DeSantis and Rory Costello, and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 References to the “World Series” in baseball scholarship typically concern the postseason championship dating back to 1903. There were postseason championships in the 19th century, sometimes labeled “World Series” by baseball scholars. Brooklyn won the American Association pennant in 1889, but lost the postseason series to the New York Giants of the National League. The following year, Brooklyn went to the NL, captured the pennant, and tied the AA’s Louisville Colonels 3-3-1. In 1899, Brooklyn won the National League championship, but there was no postseason series. In 1900, Brooklyn won the NL pennant and beat the second-place Pittsburg Pirates in a postseason series. Brooklyn’s squad was known by a few names in the 19th century, including Superbas and Bridegrooms.

2 Robert Creamer, “The Year, the Moment, and Johnny Podres,” Sports Illustrated, https://www.si.com/vault/1956/01/02/605367/the-year-the-moment-and-johnny-podres#, January 2, 1956.

3 Dan Ewald, “Johnny Podres: Induction Banquet Program Story,” National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame, http://www.polishsportshof.com/?page_id=146, August 8, 2002.

4 Creamer, “The Year, the Moment, and Johnny Podres.”

5 “Anna K. Podres,” Press-Republican (Plattsburgh, New York), http://obituaries.pressrepublican.com/story/anna-podres-1909-2007-733983252, November 29, 2007.

6 Telephone interview with Joan Podres, April 18, 2017.

7 “Moriah celebrates baseball great with Johnny Podres Day,” http://mlb-yankeesblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/moriah-celebrates-baseball-great-with.html.

8 Lohr McKinstry, “Johnny Podres remembered by his hometown,” Press Republican, http://www.pressrepublican.com/news/local_news/johnny-podres-remembered-by-his-hometown/article_ac4100d4-585e-5428-a4cf-0160b2319205.html, January 15, 2008.

9 Harold Rosenthal, “Podres, Dodger Rookie Pitcher, May Make Jump From Class D,” New York Herald Tribune, February 26, 1952.

10 “Week-End Victories, Move Bombers Into First Place By One-Half Game: Padres Wins in Debut After Poor First Frame,” Hazard Herald, May 21, 1951.

11 “Podres Pitches Two-Hit Ball; Hazard Wins 7th in Row,” Hazard Herald, June 3, 1951.

12 L.M. Sutter, Ball, Bat and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009) 128.

13 “Flock Seeks Hill Ace In Rookie,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 9, 1952.

14 “Dodgers Refuse $250,000 for Podres,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 21, 1952.

15 Harold Rosenthal, “Snider Sprains Ankle, Becomes 1st Dodger Spring Casualty,” New York Herald Tribune, March 6, 1952.

16 Harold Rosenthal, “Mound Debut of Dodger Podres Deferred by Pulled Back Muscle,” New York Herald Tribune, March 7, 1952.

17 Harold Rosenthal, “Tribe Rattles Podres in Debut With Brooklyn,” New York Herald Tribune, March 10, 1952.

18 Harold Rosenthal, “Dodgers Set Back Yankees, 7-5, With 5 Runs in 6th; Kiner Signs for $75,000,” New York Herald Tribune, March 17, 1952.

19 “Dodgers Refuse $250,000 for Podres, Brooklyn Eagle, March 21, 1952.

20 “Trade Talk Sweeps Camp,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 22, 1952.

21 Dink Carroll, “John Podres Is Winner After Tight Squeeze,” Montreal Gazette, April 25, 1952.

22 Harold C. Burr, “Podres Hailed by Dressen As Best of Young Hurlers,” March 7, 1953.

23 “Gilliam, Podres On Flock Roster,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 9, 1953.

24 “Podres, Belardi Tame Yanks,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 30, 1953.

25 Tommy Holmes, “One Pitch to Mantle and What Happened!,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 5, 1953.

26 The Ghosts of Flatbush, HBO, 2007.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Emanuel Perlmutter, “Podres’s Adirondack Neighbors Turn Out 3,000 Strong to Hail Series Hero,” New York Times, October 9, 1955.

30 “Podres’s Draft Status Uncertain After 2 Physical Examinations,” New York Times, November 15, 1955, from Associated Press.

31 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: Government Intervention,” December 29, 1955.

32 Roscoe McGowen, “Dodgers Sign Podres Though Draft Call This Spring Looms for Series Hero,” New York Times, January 19, 1956. “Dodgers’ World Series Hero Is Inducted Into Navy,” New York Times, March 20, 1956.

33 “Podres Wins for Bainbridge,” New York Times, May 24, 1956, from Associated Press, May 23, 1956. “Podres Rests Too Soon,” New York Times, July 8, 1956, from Associated Press, July 7, 1956.

34 “Navy Releases Podres of Dodgers as Physically Unfit for Military Service,” New York Times, October 27, 1956, from Associated Press, October 26, 1956.

35 Roscoe McGowen, “Pitcher Accepts Salary of $18,000,” New York Times, January 4, 1957.

36 “Podres Fans Nine,” New York Times, April 21, 1957.

37 Telephone interview with Pat Salerno, Jr. and Pat Salerno, Sr., April 18, 2017.

38 Frank Finch, “Podres Signs ’58 Dodger Contract,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 1958.

39 Frank Finch, “Podres Thinks He’ll Win 20,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1959.

40 Mal Florence, “Podres Happy Over Mound Win After Dismal Showing in Opener,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 1959.

41 Frank Finch, “Podres Fans 14 As Dodgers Win,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1959.

42 Frank Finch, “Podres to Strive for 20 Triumphs,” Los Angeles Times, January 21, 1960.

43 Frank Finch, “Podres Gets Pay Raise, Signs $22,000 Pact,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1960.

44 Frank Finch, “Podres Signs Dodger Contract for $28,500,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 1962.

45 Frank Finch, “Podres’s Arm Injured; Dodgers Lose, 8-3,” Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1962.

46 Frank Finch, “Casey’s Strategy Flops, Dodgers Win,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1962.

47 “Early Bird Podres Wires Acceptance,” Los Angeles Times, January 11, 1963.

48 Frank Finch, “Balk, Balk, Balk at the Old Ball Game,” Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1963.

49 Frank Finch, “Roseboro’s Hit in Ninth Gives Podres 1-0 Victory,” Los Angeles Times, May 17, 1963.

50 Frank Finch, “Podres Pitches On, Tooo-ooo-ooo!,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1963.

51 Frank Finch, “Podres Throws Blank-Et Over Bucs,” Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1963.

52 Frank Finch, “Podres’s No-Hitter Spoiled In Ninth,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1963.

53 “‘I Said I Was Tired…Why Kid Yourself?…We Had Perranoski,’” Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, October 4, 1963.

54 “Podres Signs for $35,000,” Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1964.

55 “Podres Out for Week,” Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1964.

56 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Lose Podres, T. Davis — Game,” Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1964.

57 “Dodgers Offer Podres to Colts, but It’s Nixed,” Los Angele Times, May 8, 1964.

58 Frank Finch, “Koufax, Podres Still Below Par,” Los Angeles Times, May 12, 1964.

59 Frank Finch, “Podres’s Elbow Injury Traced to Childhood,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1964.

60 John Hall, “100 Hot Needles,” Los Angeles Times, May 24, 1964.

61 Ibid.

62 Ibid.

63 “Podres Ok After Elbow Operation,” Los Angeles Times, June 12, 1964.

64 “Podres Ordered to Stop Throwing,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1964.

65 John Hall, “Leimert Park AC,” Los Angeles Times, November 7, 1964.

66 Frank Finch, “Podres Faces Big Pay Cut From Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, January 26, 1965.

67 Frank Finch, “Podres Tries New Slider — It Works,” Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1966.

68 Telephone interview with Joan Podres.

69 Charles Maher, “Dodger Deal Turns Podres Into Tiger,” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1966.

70 Jack Lang, “Now or Never for Mets’ Reniff; He’ll Make Squad or Pack It In,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1968.

71 Bob Hunter, “Bailey Finds a Home — He’s All Set at Dodger Hot Corner,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1968.

72 Les Biederman, “Clemente — The Player Who Can Do It All,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1968.

73 Richard Goldstein, “Johnny Podres, Series Star, Dies at 75,” New York Times, January 14, 2008.

Full Name

John Joseph Podres

Born

September 30, 1932 at Witherbee, NY (USA)

Died

January 13, 2008 at Glens Falls, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.