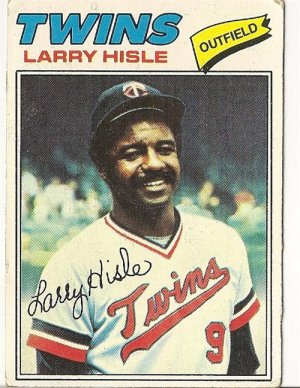

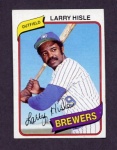

Larry Hisle

Consider the two nearly identical rookie seasons below:

| AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | AVG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player #1 | 464 | 59 | 127 | 22 | 5 | 20 | 68 | .274 |

| Player #2 | 482 | 75 | 128 | 23 | 5 | 20 | 56 | .266 |

These highly acclaimed prospects started 18 years apart. Both were center fielders, blessed with power and speed. Player #1 was the runaway choice for National League Rookie of the Year and had one of the greatest careers in major-league history. Player #2 finished a distant fourth in the N.L. Rookie of the Year voting, suffered a “sophomore jinx” that nearly ended his career, rebounded with some excellent seasons, but was derailed by injury. Though they were playing for different teams, Player #1 offered batting tips to Player #2 at one point during the latter’s rookie season.1

These highly acclaimed prospects started 18 years apart. Both were center fielders, blessed with power and speed. Player #1 was the runaway choice for National League Rookie of the Year and had one of the greatest careers in major-league history. Player #2 finished a distant fourth in the N.L. Rookie of the Year voting, suffered a “sophomore jinx” that nearly ended his career, rebounded with some excellent seasons, but was derailed by injury. Though they were playing for different teams, Player #1 offered batting tips to Player #2 at one point during the latter’s rookie season.1

Player #1 is Hall of Famer Willie Mays – Player #2 is Larry Hisle.2

Hisle, an Ohio native, grew up playing sports alongside fellow major-league star Al Oliver. He was also a fine basketball player but passed up a possible NBA career to sign with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1965. His most productive seasons came more than a decade later for the Minnesota Twins and Milwaukee Brewers. He made two All-Star appearances and received Most Valuable Player consideration in two of his 14 major-league seasons. Yet, in the course of attaining this success, his career encountered various detours.

Larry Eugene Hisle (pronounced HY-sul) was born on May 5, 1947, in Portsmouth, Ohio. This municipality along the northern banks of the Ohio River has been home to other baseball notables such as Branch Rickey and Al Bridwell. Gene Tenace, who grew up and went to high school in nearby Lucasville, played American Legion ball in Portsmouth with Hisle and Oliver. Hisle’s life echoes the 19th century rags-to-riches stories of Horatio Alger. After a childhood of want and pain, Hisle’s determination and continued hard work eventually made him wealthy – though family and friendship were what made him happiest.

After baseball, Hisle’s message of endurance has resonated. His memory of personal hardship and generous spirit have motivated him to help numerous children in need. This calls baseball’s foremost legend to mind: Babe Ruth.

Larry Hisle was the only child of Hubert and Claudine Hisle. Claudine, a big baseball fan, named her son after Lawrence Eugene “Larry” Doby, the African-American baseball star who made his debut with the Cleveland Indians just two months later.3 Alas, Larry lost both parents at an early age. When he was just 10 years old, his father suffered a devastating brain hemorrhage – “Jupiter” Hisle never again recognized his son (he eventually died in 1962).4 Single mother Claudine struggled to keep basic utilities running. “We were on welfare and things were tough,” Larry recalled in 1978. “We used to get checks around the fourth of each month and around the last week of the month things became extremely difficult.”5 Yet even though they were poor, Hisle called himself “the happiest kid on the planet” thanks to his mother. However, several months after her husband was stricken, Claudine Hisle died from a kidney infection – it was even more poignant because she hadn’t been able to afford earlier treatment.6

Hisle lived for several years with his mother’s sister and then was adopted by Orville Ferguson, a successful construction contractor, and his wife Kathleen. The foster parents “treated me better than any son could be treated.”7 Yet his mother had a lasting impact, instilling “a will to settle for nothing less than the absolute best that life had to offer.”8 Hisle channeled his grief by throwing himself into sports with a self-imposed goal of making his beloved mother proud. “I lived in a housing project adjacent to a park and I’d go out there every morning and practice,” Hisle said. “When I’d begin to get tired and think of going home, I would ask myself, ‘What would my mother do if she were in my shoes?’ She would do her absolute best to be the best she could be. I’d stay out there and work harder.”9

The hard work paid off handsomely; Hisle became a high school All-American in both baseball and basketball. He was also an honor student. Before long, colleges were furiously bidding for his talents, with some notable recruiters. NBA superstar Oscar Robertson called on behalf of the University of Cincinnati. 10 Hisle visited Ohio State University many times, meeting with the state’s Governor, Jim Rhodes, plus Buckeye basketball greats John Havlicek and Jerry Lucas.11

Hisle signed a letter of intent with Ohio State – but the Phillies, led by scout Tony Lucadello, had also been pursuing him weekly. Lucadello later described what impressed him while scouting Hisle in an American Legion tournament game. “Portsmouth was playing in Athens on the diamond of Ohio University. . .Larry put three home runs out of the park, one to left that bounced off the gymnasium, one to center and a third to right. . .Larry’s awesome display of power was like nothing I had ever witnessed.”12

Lucadello – joined by Phillies owner Bob Carpenter, general manager John Quinn, and farm director Paul Owens – convinced Hisle that baseball was the way to go. A hefty signing bonus, reportedly in the $40,000-$60,000 range, got the young man to sign with the Phillies in August 1965.13 He had been chosen in the second round (38th pick overall) in the major leagues’ first-ever amateur draft. Hisle attended Ohio State that fall (he eventually continued his education there during the baseball off-seasons) but was ineligible to play basketball.

By the following summer, the 19-year-old found himself nearly 1,000 miles away from home playing for the Huron (South Dakota) Phillies in the Northern League (short-season Class A). The schedule was short – 70 games – and curtailed even more by the discovery of Hisle’s previously unknown spinal defect (which kept him out of military service). Still, a .433 batting average and .667 slugging percentage in 60 at-bats showed the Phillies why the large signing bonus was warranted.

Hisle started the following spring with the Tidewater (Virginia) Tides of the Carolina League (Class A). He got off to a strong start, with two home runs and four RBIs on April 19, and made the league’s All-Star Game. He “topped the East [squad’s] win with three straight hits and two RBIs before being lifted.”14 By season’s end, Hisle ranked among the league leaders in every offensive category (including .302-23-78 in the major three). He fell just short of winning the Most Valuable Player award in what was reported to be the closest voting in the league’s 22-year history to that point. The winner was his future teammate with both the Phillies and Brewers, Don Money (then a shortstop).

On December 15, 1967, the Phillies traded Jim Bunning, their mound ace and future Hall of Famer, to the Pittsburgh Pirates for a package of youngsters that included Money. Hisle and Money were considered key components in the parent team’s future, even though they had played fewer than 500 pro games between them, and none above Single-A ball. The prospects, both just 20 years old, appeared destined for further minor league development – but instead they both made the Phillies’ starting lineup on Opening Day 1968. A strong spring, combined with nagging injuries to the Phillies’ veteran shortstop and center fielder, contributed to this startling maneuver. Yet as Manager Gene Mauch said, “I’ve got to see what [Hisle and Money] can do…They’re exceptional young men, and exceptional young men do exceptional things.”15

Hisle started three times, pinch-hit once, and appeared in three more games as a late-inning defensive replacement. He was 4 for 11 (.364) in his limited duty. Both he and Money were optioned to the team’s Triple-A affiliate in San Diego in late April, and both continued to do well, finishing 1968 with identical .303 batting averages. Hisle’s season ended in July, however, after he was diagnosed with hepatitis.

Meanwhile, the Phillies plummeted to a distant seventh-place finish, and the club evaluated its older veterans amid rebuilding. As part of this process, they left Tony González, their starting centerfielder for most of the 1960s, unprotected in the expansion draft. The San Diego Padres claimed González, and the door was fully open for Hisle to step into the centerfield position.

Hisle was again in the Opening Day lineup when the Phillies opened their 1969 season in Chicago. He hit just .159 in April, though that included his first big-league homer. It came on April 21 at Shea Stadium off Gary Gentry of the Mets. Hisle got his first four-hit game in the majors on May 2 and another on May 18. He continued to heat up as the summer went on and finished the season batting .266, with 20 homers (second on the team behind Dick Allen) and 56 RBIs. It would likely have been more except for a thumb injury – later determined to be a hairline fracture – that limited Larry to 23 at-bats after September 1. Had he sustained his output over the full year, Hisle would likely have placed higher in the Rookie of the Year voting, or won outright. As consolation, he was eventually selected to the Topps Rookie All-Star Team, along with teammate Don Money and childhood competitor Al Oliver.

Hisle was again in the Opening Day lineup when the Phillies opened their 1969 season in Chicago. He hit just .159 in April, though that included his first big-league homer. It came on April 21 at Shea Stadium off Gary Gentry of the Mets. Hisle got his first four-hit game in the majors on May 2 and another on May 18. He continued to heat up as the summer went on and finished the season batting .266, with 20 homers (second on the team behind Dick Allen) and 56 RBIs. It would likely have been more except for a thumb injury – later determined to be a hairline fracture – that limited Larry to 23 at-bats after September 1. Had he sustained his output over the full year, Hisle would likely have placed higher in the Rookie of the Year voting, or won outright. As consolation, he was eventually selected to the Topps Rookie All-Star Team, along with teammate Don Money and childhood competitor Al Oliver.

The Phillies opened 1970 with a largely new cast. Gone were such long-time notables as Allen, Johnny Callison, and Cookie Rojas. Rookies Larry Bowa and Denny Doyle came in, along with manager Frank Lucchesi, finally getting his shot in the majors. For the second straight season, the Phillies avoided a last-place finish in the NL East division only thanks to the Montreal Expos, the league’s other expansion team. Hisle fared even worse than his team. He had a good spring and a strong start, but then went into a severe and extended slump. He was below the Mendoza Line for nearly half his season, and strikeouts – a concern dating back to his minor-league days – were again a problem (more than one in every three at bats). A flurry in late September lifted him over.200, but by that point Hisle was a platoon player. He appeared in only 126 games with 405 at-bats overall. He was deemed vulnerable to high, inside fastballs, and Lucchesi offered that in “some way, we’ve got to get Larry started [again].”16

Intense training in the Florida Instructional League was the perceived solution, and Hisle responded positively. The Phillies were confident that the slugger who had displayed such early promise would return. Indeed, when the Pittsburgh Pirates dangled former batting champ Matty Alou in trade for a package that included Hisle, the Phillies declined. Unfortunately, management’s confidence did not extend past spring training. The Phillies again platooned Hisle, starting him only against lefty pitchers. A mere 14 at-bats in April further indicated the team’s lost confidence; in early June, they optioned Hisle to Triple-A Eugene. He did well there and was recalled in September, but finished the year at just .197-0-3 in 36 games.

Less than a month later, Hisle’s ties to the Phillies were severed. He was traded even-up to the Los Angeles Dodgers for first baseman Tommy Hutton. The deal required the approval of Bob Carpenter – showing that certain circles of the organization still held Hisle in high regard. Yet the trade also re-opened an ugly, lingering side of the Philadelphia franchise: its race relations.

Over the years, Hisle had been variously described in the oft-critical Philadelphia press as “polite [and] soft-spoken,”17 “modest [and] unassuming,”18 and “mild-mannered.”19 So when this genuinely nice, honest athlete opened up about his perception of the Phillies’ negative treatment of African-American players, his opinions made news. Long-respected columnist Allen Lewis latched on and issued a withering appraisal of both the checkered history – the Phils were the last National League team to employ an African-American player – and the problems the club had in retaining once-budding stars such as Richie Allen, Grant Jackson and Johnny Briggs. Uncited, but certainly relevant, was the team’s lack of patience with African-Canadian Ferguson Jenkins, who became a Hall of Famer with the Chicago Cubs. Bob Carpenter admitted, “Our track record hasn’t been good”, and club officials stated their commitment toward resolving the situation.20

Hisle was moving on to the team renowned for breaking the color barrier with Jackie Robinson – but he never played a big-league game in Dodger blue. Los Angeles was on the verge of becoming one of the most successful teams of the decade. A lot of young talent was on the way up, especially in the infield – but in 1972 the starting outfielders were all veterans: Willie Davis in center, flanked by Manny Mota and Frank Robinson. Bill Buckner and Willie Crawford were their backups. Hisle could not break through and was assigned to Triple-A Albuquerque. There he mounted the comeback that defined the rest of his professional career. His numbers – .325-23-91 – ranked him with teammate Ron Cey, Gary Matthews, and Mike Schmidt among the Pacific Coast League’s leaders. It was reported that “Hisle [was] probably the most scouted player in the Pacific Coast League… [with] no fewer than nine major league scouts watching him nightly.”21

The Dodgers shipped him to St. Louis for two minor-league hurlers. Yet just over a month later, the Cardinals flipped Hisle to Minnesota for veteran reliever Wayne Granger.

In Hisle, the Twins were perceived to be filling various needs going into the 1973 season – greater defensive range in the outfield, plus a combination of speed and power from the leadoff position. Aside from his continued propensity to strike out, Hisle filled those needs well over a very successful five-year run with the Twins. As it developed, though, he seldom led off after 1973.

There were a couple of interesting side notes to the 1973 season. After a freak accident, Hisle became the Twins’ designated hitter in the opening game of spring training – the first big-league DH ever, albeit in exhibition play. He made the new rule look good – though baseball purists will never agree – by hitting two home runs (including a grand slam) while driving in seven runs. Also, the Twins had an odd number of African-American players, so Hisle had a white roommate on the road. It’s amusing in retrospect, but this was called “one of the most progressive moves in the franchise’s history.”22

Hisle took a modest step up in 1974, lifting his basic batting line from .272-15-74 to .286-19-79. His OPS rose from .773 to .818. His club did not improve quite so much, though; the Twins finished 82-80, one game better than the prior season.

Minnesota had not been truly competitive since winning the AL West in 1970, but Hisle – now batting in the middle of the lineup – was a big contributor to a team that hoped to be on the rise. “I was having the best season of my career,” he said that October. 23 He may have had additional incentive because he was not listed on the computerized All-Star ballots.

Unfortunately, a bone spur in his elbow (and subsequent surgery) limited Hisle to just 35 at-bats after June 17. In his absence, the team fell below .500 and finished 20 1/2 games behind the division champion Oakland Athletics. Manager Frank Quilici was fired, and Hisle was reunited with his first major-league skipper, Gene Mauch.

Shortly after taking the helm, Mauch expressed a need to improve the Twins’ defense and run production.24 The club did score slightly more in 1976, leading the AL in runs with a small-ball approach that emphasized sacrifice bunts and stolen bases. Unfortunately, they were also third in the AL in runs allowed, fueled by a league-leading 172 errors. Still, by closing the season with a 21-8 run, the Twins finished third in the division, just five games behind Kansas City.

Hisle’s season mirrored the team’s offense. He led the Twins in RBIs with 96, while hitting 14 homers and batting .272. On June 4, he became the third player in Twins’ history to hit for the cycle. Yet he also laid down 11 sacrifice bunts and stole 31 bases, both career highs.25 Speed had always been part of Hisle’s arsenal, but Mauch gave him the green light. For example, on June 30, Hisle stole four bases against the Royals, a team record that he still held alone as of 2012. Small ball seemed to agree with Hisle – but he would come to flourish as a power hitter.

The Twins spent much of 1977 in first place but collapsed down the stretch (something Mauch could remember most painfully from his 1964 Phillies). Their distant fourth-place finish disappointed fans, team, and Hisle himself, despite his personal success. Hisle started strongly and stayed consistent –his batting average never dipped below .290 after May 13. He finished at .302– the only time he hit .300 over a full season in the majors – and led the AL with 119 RBIs. His 28 home runs also placed him among the league’s top 10. He made the American League All-Star squad for the first time and got some votes for Most Valuable Player.

His performance also came against a backdrop of long and sometimes bitter contract negotiations. The tone was actually set after Hisle won in arbitration before the 1974 season. In response, Twins owner Calvin Griffith –a noted tightwad – allegedly said that “he would get back the money…even if [the team] had to trade” Hisle.26 The Twins submitted a two-year pact before the 1977 season, but Hisle discovered that the amount “wasn’t [nearly] as flattering” as the period.27 Considering that other star outfielders such as Reggie Jackson, Joe Rudi and Gary Matthews had signed attractive free-agent deals, Hisle contemplated playing out his contract and exploring the market himself.

Negotiations continued throughout the 1977 season, and despite hopeful indications of closure, terms could not be reached. Time ran out and Hisle became a free agent. He was courted aggressively by numerous clubs – including the Texas Rangers, whose owner was fined on charges of tampering. Hisle eventually signed with the Milwaukee Brewers for a structured six-year contract exceeding $3 million, a vast increase over the reported $47,200 he’d earned the year before.

The Brewers (formerly the Seattle Pilots) had never finished above .500 in nine seasons. The perceived route to success was free agency. The club had already made a splash by signing Oakland’s slugging third baseman Sal Bando a year earlier. The lineup also included Cecil Cooper, future Hall of Famers Robin Yount and Paul Molitor, and Hisle’s former teammate Don Money. The team looked like a contender in the AL East.

Hisle immediately contributed to this powerful squad – he became the AL’s first Player of the Week in 1978 and was second runner-up for Player of the Month for April. Though he missed the second half of May, Hisle returned and had his strongest season overall. He hit .290, with a personal best of 34 homers (second in the league behind Jim Rice) and 115 RBIs (third after Rice and Rusty Staub). His OPS of .906 was a career high. Milwaukee won 93 games, but still finished third, behind the New York Yankees – the eventual world champions – and Boston. Yet Hisle’s efforts were recognized; he became an AL All-Star for the second time, and he finished third in the MVP voting behind Rice and Ron Guidry. The Milwaukee chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America named him team MVP. Hisle was still just 31, and a league MVP award seemed within his grasp.

Yet after an excellent start in 1979 – .341, 3 home runs and 10 RBIs in 10 games – Hisle suffered a devastating injury in a game at Baltimore on April 20. That summer he said, “I was playing left field. . . and had six balls hit out to me. . . I had to make hard throws on all six of them, and on the last one, I felt something snap in my shoulder.”28 The diagnosis was a torn rotator cuff – the severity was the fourth degree out of five.29

Determined to play through the pain, Hisle served as Milwaukee’s designated hitter over the next two weeks, but he eventually was forced to yield and went on the disabled list. An exercise program to strengthen the shoulder – in lieu of surgery – took longer than expected, and Hisle did not make another appearance until early September. Even then, he was limited to eight at-bats before he was shut down.

Hisle continued his hard exercise over the off-season – he was reluctant to undergo surgery, in part because he saw that other victims of rotator-cuff tears weren’t the same after their operations. He pointed to pitchers Don Gullett and Wayne Garland, as well as fellow outfielder Hal McRae.30

On Opening Day 1980, he was back in uniform and ready to play. Milwaukee used him strictly as a DH, bringing him along slowly to avoid aggravating the injury. He hit two homers on May 17 – the last of eight times he achieved this feat – but two days later, he hurt the shoulder again while sliding into second base. Initially, it was thought that rest would suffice, but subsequent tests “revealed another tear in the rotator cuff. . .[and] surgery was performed by Dr. Frank Jobe,” innovator of the Tommy John procedure. 31

A second, related procedure – the removal of a bone spur from Hisle’s right shoulder – was required in July 1981. Along with the players’ strike, that limited Hisle to just 87 at-bats for the season. He doggedly pursued his comeback against long odds – he later said, “[It] took more guts, work and determination than everything else I accomplished in life,” ranking it right along with overcoming the death of his mother.32 However, he fared no better in 1982. He made a total of just nine appearances and 31 at-bats before another disabled list assignment. His last of 166 major-league homers came as a pinch-hitter off Kansas City’s Paul Splittorff on May 3 – his final game in the majors was just three days later.

Hisle still held out hope of coming back that fall, but he said that the variety of surgical procedures – five areas of his shoulder had been worked on – and rehabilitation had damaged the shoulder enough. “The team doctor [Paul Jacobs] said any part of the body can take only so much.”33 He announced his retirement that off-season. The same report stated that he would “become a special instructor in the Brewers’ minor league system and a scout…work[ing] with the Brewers’ Class A and rookie league teams.”34

Over the next 15-plus years, Hisle served in a similar capacity with his first pro organization, the Phillies. He also had brief coaching stints in the minors with the Houston Astros (1989), Toronto Blue Jays (1990-91), and the Brewers again (1997). From 1992 through 1995, Hisle was with the Blue Jays’ parent team as batting coach. He won a strong review after the 1992 season, the first of back-to-back World Series championships for Toronto. “The team’s improved hitting…benefited from Hisle’s emphasis on patience and discipline.”35 In 1993 a trio of Blue Jays, John Olerud, old teammate Paul Molitor, and Roberto Alomar finished one-two-three in the American League batting race. That feat had been accomplished only once before, by three Phillies players exactly 100 years earlier.

Hisle and his wife, the former Sheila Sanford, were married on September 28, 1970. She was a secretary for a law firm that handled some Phillies affairs. They had one child, a son named Larry Jr.36 The Hisles had always extended themselves in charitable efforts throughout his baseball career. But after he retired to his home outside Milwaukee, this endeavor went into overdrive. The man once dubbed the “honorary captain of the major league Nice Guy Team”37 demonstrated an even deeper meaning of nice-guy.

Rather than plush, multi-million-dollar stadiums and the adulation of thousands of sports fans, Hisle sought out community group homes, detention centers, and public schools. He assisted youngsters of little means, with the profound appreciation of social workers, teachers and judges. In addition to his status as the Brewers’ Manager of Youth Outreach, he has joined forces with his son, Larry Jr., a strong basketball player who also performed in independent baseball leagues from 1995 through 1997. Larry Jr. founded Directors of Continuing Services, a firm that provides psychological, educational and mentoring services to children and families. His father, the orphan who had once longed for such assistance, stepped into a mentoring role himself. He has often taken on round-the-clock responsibilities to help those most at risk.

“I’m only doing something for these kids that should be done for every kid in the country,” says the ever-humble ex-athlete renowned for never turning down a request for help. His expressed goal is to “manufacture dreams” for those that “society has written off,” and in this capacity, Hisle has been described as “one of the best things happening in Milwaukee.”38

This man with the infectious smile had never been forgotten in his native Portsmouth either. Around 2,000 of his hometown fans celebrated “Larry Hisle Day” at Cincinnati’s old Crosley Field in August 1969.39 Portsmouth held another such day in October 1977, dedicating a city park in Hisle’s name. The affection ran both ways, as a Twins teammate, the late Lyman Bostock, remembered. “When I met this fellow, all he would do is talk about Portsmouth.”40

People readily respond to Hisle in the most positive ways, as these descriptions demonstrate:

“The kind of player kids should look up to…without a doubt, one of the nicest men I’ve ever known.”

– George Bamberger, former Brewers manager41“A wonderful human being…he is one of the nicest human beings I’ve ever met in my life.”

– Bud Selig, former Brewers owner/Commissioner of Major League Baseball42“No matter what good things have been written about him, he’s even better…one of the nicest ballplayers ever to come in here.”

– Jim Ksicinski, former Milwaukee clubhouse attendant.43

Last revised: April 25, 2014

Acknowledgments

Thanks for assistance from Jan Larson, Jim Baker, Rory Costello, and the unknown sportswriter who originally came up with the Mays/Hisle comparison that I never forgot.

Sources

Books

Jael Ealey Richardson, The Stone Thrower, Markham, Ontario: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2012, This book is by the daughter of Chuck Ealey, a former pro football player in Canada who was a close friend of Larry Hisle’s as they grew up in Portsmouth.

Newspaper articles

Gary D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, November 8, 2011 (http://www.jsonline.com/sports/brewers/hisle-goes-to-bat-for-troubled-youth-nr2vf38-133507288.html)

Internet resources

Adam McCalvy, “Where have you gone, Larry Hisle?” MLB.com, June 12, 2002 (http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20020612&content_id=51295&vkey=news_mil&fext=.jsp&c_id=mil)

Aaron Gleeman, “Top 40 Minnesota Twins: # 27 Larry Hisle,” December 28, 2010, http://aarongleeman.com/2010/12/28/top-40-minnesota-twins-27-larry-hisle/

http://www.baseballlibrary.com/ballplayers/player.php?name=Larry_Hisle_1947

Notes

1 Associated Press, May 19, 1969. The San Francisco Giants visited Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia for a weekend series.

2 “Larry Hisle Strives for Improvement Over 1969 Despite Good Statistics,” Associated Press, March 7, 1970. This may not be the exact story that the author remembers, but it is very similar.

3 Jael Ealey Richardson, The Stone Thrower, Markham, Ontario: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2012,

4 Richardson, The Stone Thrower. Hubert Hisle’s death record – ancestry.com

5 Lou Chapman, “Welfare to Well Off Is Story of Hisle’s Life,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 1, 1978, Part 2, Page 2

6 Gary D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth,” Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, November 8, 2011

7 D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth”

8 Richardson, The Stone Thrower

9 D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth”

10 Allen Lewis, “Hisle Looks Like Money In Bank,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1968, 21.

11 Lee Caryer, “The Buckeye Who Never Played A Game,” Bucknuts.com website, December 27, 2010 (http://ohiostate.247sports.com/Article/OSU-Hoops-Becomes-Black-and-White-35287)

12 David V. Hanneman, Diamonds in the Rough: The Legend and Legacy of Tony Lucadello, Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1990. Quoted in Steve Triplett, “Lucadello Book ‘Real Diamond,’” Portsmouth Times, February 26, 1990, 11.

13 Lewis, “Hisle Looks Like Money In Bank”

14 Tom Northington, “Slugger Walton Hero of Carolina All-Star Game,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1967, 39.

15 Allen Lewis, “Frosh Hisle, Money Spring Surprises – Earn Phillies Jobs,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1968, 24.

16 Allen Lewis, “Phils Sink Outfield Bundle on Gamble,” The Sporting News, October 31, 1970, 48.

17 Allen Lewis, “Phils Figure on Hisle in Center, Despite Mini-Mini Experience,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1968, 52.

18 Allen Lewis, “Hisle Severe Self-Critic…But Phils Say He’s Great,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1969, 20.

19 Allen Lewis, “Phils Attack Old Problem: Handling of Negro Players,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1971, 48.

20 Lewis, “Phils Attack Old Problem: Handling of Negro Players”

21 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1972, 32.

22 Bob Fowler, “Possum, Bam-Bam Strike Terror for Twins,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1973, 19.

23 Bob Fowler, “Twins’ Fortunes Faded Following Hisle’s Injury,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1975, 19.

24 Bob Fowler, “A New Twist for the Twins: Mauch Will Stress Defense,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1976, 35.

25 Both Hisle and Rod Carew had 30-plus stolen bases, the only time in Twins history (through 2012) that two players achieved that threshold in the same season. Indeed, only six other Twins players have ever had 30 or more steals in a season.

26 Bob Fowler, “Consultation With Rowe Bolsters Brye,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1974, 28.

27 Bob Fowler, “Twins’ Low-Ball Pay Pitch Jolts Hisle,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1977, 31.

28 “Portsmouth native roots for team,” Pomeroy (Ohio) Daily Sentinel, July 19, 1979, 4

29 Don Willman, “Hisle Faces Probable End of Career,” Portsmouth Times, September 10, 1982, 10.

30 Bob Wolf, “Hisle getting himself armed for 1980,” Milwaukee Journal, February 15, 1980, Part 2, page 1.

31 “Brewers’ Larry Hisle Undergoes Surgery,” The Sporting News, August 2, 1980, 12.

32 Willman, “Hisle Faces Probable End of Career,” D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth”

33 Willman, “Hisle Faces Probable End of Career”

34 Tom Flaherty, “Good Health Meant Success for Money,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1983, 47.

35 Neil MacCarl, “Toronto Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1992, 23.

36 “Sheila Hisle Enjoys Pro Baseball Life,” Portsmouth Times, October 27, 1977. Online obituary of Sheila Sanford’s mother, Dorothy (http://www.krausefuneralhome.com/obituary.php?id=2631)

37 Mike Gonring, “Hisle a Brewer Money Player in All Respects,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1978, 16.

38 D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth”

39 Don Lundy, “Portsmouth Area Fans Treat Hisle to Big Day,” Portsmouth Times, August 11, 1969, 1.

40 Dan Montgomery, “Area Pays Tribute to Larry Hisle,” Portsmouth Times, October 28, 1977, 1, 6.

41 D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth”

42 D’Amato, “Ex-Brewer Hisle goes to bat for troubled youth”

43 Mike Gonring, “Realtor Clubhouse King to Brewer Visitors,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1979, 18.

Full Name

Larry Eugene Hisle

Born

May 5, 1947 at Portsmouth, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.