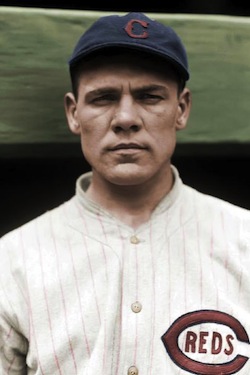

Pete Appleton

In September 1927, the Cincinnati Reds brought up a 23-year old right-handed pitching prospect named Pete Jablonowski for a late-season look-see. Although he made a good first impression, going 2-1 with a 1.82 ERA and a shutout victory, Jablonowski struggled the following year in 31 games. In 1930-1931, however, he saw considerable service with the Cleveland Indians, posting a combined 12-11 log over two seasons of spot starting and relief work. But Jablonowski was thereafter cast adrift again, with only a brief stint with the Boston Red Sox and a single game appearance for the New York Yankees preceding his return to the minors.

In September 1927, the Cincinnati Reds brought up a 23-year old right-handed pitching prospect named Pete Jablonowski for a late-season look-see. Although he made a good first impression, going 2-1 with a 1.82 ERA and a shutout victory, Jablonowski struggled the following year in 31 games. In 1930-1931, however, he saw considerable service with the Cleveland Indians, posting a combined 12-11 log over two seasons of spot starting and relief work. But Jablonowski was thereafter cast adrift again, with only a brief stint with the Boston Red Sox and a single game appearance for the New York Yankees preceding his return to the minors.

Three seasons and one legal name change later, he resurfaced as Pete Appleton, notching a career-best 14 wins for the 1936 Washington Senators. For the next nine years, with time out for World War II naval service, Appleton remained in uniform, hurling his final major-league game as a 41-year-old in September 1945. The remainder of his life was likewise devoted to the game, first as a player-manager in various minor leagues and thereafter as a fulltime scout for the Senators and Minnesota Twins. By the time of his death in early 1974, Pete Appleton had spent 47 years associated with professional baseball.

A life in baseball was far from foreordained for Peter William Jablonowski when he was born in Terryville, Connecticut on May 20, 1904. It certainly was not the ambition harbored for the oldest of their four boys by Pete’s parents, Alex Jablonowski, a lock maker of Polish descent born in Pennsylvania, and wife, Mary.1 With the musical talents of her eldest child evident from an early age, Mary Jablonowski, in particular, envisioned her son forging a career in the arts as a concert pianist, perhaps becoming another Paderewski (rather than another Coveleski).2 But Pete’s athletic abilities could not be denied. At Terryville High School, he excelled in basketball and was a premier track and field man, setting a state record for the shot put.3

But it was on the baseball diamond where Pete really shined. A converted shortstop, Jablonowski pitched high school no-hitters against Woodbury and Litchfield, striking out 24 batters in the game against Woodbury.4 He also attracted attention pitching in the Waterbury City Amateur League. Although a professional career beckoned, furthering Pete’s education was the priority of his parents. Accordingly, he matriculated to the University of Michigan as a music studies major, his enrollment arranged by Terryville High School Principal Harry Fisher, who just happened to be the older brother of Wolverines baseball coach Ray Fisher, formerly a standout major-league pitcher.5 At Michigan, Pete Jablonowski performed capably in both the classroom and on the field. An excellent student, Pete was a member of the Polonia Literary Society at the university, as well as a sought-after pianist and fledgling band leader. On the diamond, he alternated between the mound and third base, where he formed part of the tongue-twisting around-the-horn combo of Jablonowski to Puckelwartz to Oosterban.6 By his senior year, Pete was the pitching ace of the Wolverines’ 1926 Western Conference (Big Ten) championship team. At campaign’s end, he then commenced his professional baseball career, signing with the Waterbury Brasscos of the Class A Eastern League.7

Joining the club in June, Jablonowski posted unspectacular numbers (7-6, with a 4.30 ERA in 23 games) for the lackluster seventh-place Brasscos. But his maiden pro season was highlighted by a 3-0 no-hitter against Bridgeport on August 17, and a last-day 15 strikeout relief appearance versus New Haven. This latter performance was witnessed first-hand by Cincinnati Reds manager Jack Hendricks, and resulted in Jablonowski being drafted by the Reds in the offseason. Optioned to Eastern League Hartford the following spring, Pete was a creditable 9-8 with a 2.99 ERA in 226 innings for the sixth-place Senators, earning himself a late-season promotion to the big club. On September 14, 1927, Jablonowski made his major-league debut, relieving starter Jakie May in what appeared to be a lost cause against the Phillies. A ninth-inning rally, begun with an RBI single by the good-hitting Jablonowski and completed by a bases-loaded triple by Rube Bressler, made Pete the winning pitcher. After several more relief appearances, he got his first start against Brooklyn, but was himself the victim of a ninth-inning rally that cost him a 5-3 defeat. On October 2, Pete bounced back, outdueling Pittsburgh’s Lee Meadows with a four-hit 1-0 complete game victory. In six games for the 1927 Reds, Jablonowski finished at 2-1 over 29 2/3 innings, but had recorded only three strikeouts (compared to 17 walks), an early indication that his stuff was something less than overpowering when pitted against major-league opposition.

Pete made the Reds roster the following spring but did not stay with the club the entire season, being optioned at mid-year to the Columbus Senators of the American Association. Before he went down, Jablonowski experienced the great thrill of his early baseball career. Taking over for a battered Jakie May in the first inning of a June contest, Pete thereafter outdueled Dazzy Vance for a 5-3 win in 11 innings. Recalled from Columbus in August, he ultimately saw action in 31 contests for the 1928 Reds, going 3-4 with a 4.68 ERA, mostly in relief. The following season, Jablonowski was once again assigned to Columbus, where he posted a solid 18-12 mark in 246 innings pitched. As the Senators’ campaign drew to a close, Cincinnati again recalled Pete, but Commissioner Landis, disturbed by the coziness of the Cincinnati-Columbus arrangement, would not allow it. He voided the transfer and declared the now 24-year-old hurler eligible for the upcoming draft. With that, Columbus promptly sold Jablonowski to the Cleveland Indians for $20,000.8

While waiting for his American League career to commence, Pete took post-graduate courses at the Michigan Conservatory of Music and sought engagements as a pianist and band leader. Back on the field, he spent the next two seasons entirely with Cleveland, going 8-7 (1930) and 4-4 (1931), again mostly in relief outings but with an occasional start. As in the NL, American League hitters did not find Jablonowski’s stuff overpowering, and he walked more batters (82) than he fanned (70). He began the 1932 season with several dismal relief appearances for the Indians, and was then traded to the Red Sox for 18-game loser Jack Russell. Pete’s downward slide continued in Boston. After going 0-3 in 11 games, he was sent to the Sox’ International League farm team in Newark. There, Pete suddenly regained his form, posting a sterling 11-1 record in 12 starts for the pennant-bound Bears. But in the minor-league Little World Series against the American Association champion Minneapolis Millers, he dropped his only decision, a route-going 3-2 loss in 10 innings.

That winter, the upturn in Pete Jablonowski’s fortunes extended from the diamond into his personal life. At a Manhattan hotel dinner dance, the handsome ballplayer-pianist met Aldona Leszczynski, an attractive female attorney from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and courtship promptly ensued. On November 9, 1933, the two were wed at St. Stephen’s Roman Catholic Church in the bride’s hometown, the place where the newlyweds would reside throughout their 40-year marriage. Pete’s marital status was not the only thing that changed that year. Assisted through the legal process by Aldona, Pete officially changed his surname from Jablonowski to Appleton, the Polish word jablon being the equivalent of apple in English.9

Back on the baseball front, Pete was now the property of the New York Yankees, being among the assets acquired when the Newark franchise was purchased from Boston. He got little chance with New York, his tenure as a Yankee confined to a two-inning relief stint in a lone 1933 contest.10 He spent most of the season with Newark, going 13-7 for the Bears. Thereafter, Pete was sold to Baltimore of the International League which subsequently optioned him to the rival Rochester Red Wings.

After he had posted a combined 11-13 record for the 1934 campaign, Baltimore reclaimed Pete Appleton and then sold him to another International League competitor, the Montreal Royals. There, the rejuvenation of his pitching career would begin. Going 23-9 with a fine 3.17 ERA for the pennant-bound Royals, Pete Appleton was the IL’s leading winner and generally acclaimed the circuit’s best pitcher. That winter, appreciative Montreal owner-manager Frank Shaughnessy cleared the way for Pete to get another major-league shot, selling his rights to the Washington Senators for $7,500.

The 5’11” and 183 lb. veteran was now almost 32 years old. As described by Washington Post sports columnist (and soon-to-become ardent Pete Appleton booster) Shirley Povich, Appleton was a deliberate worker who did not throw hard, delivering his assortment of pitches via an over-the-top motion.11 But while his stuff was still adjudged no more than adequate by major-league standards, Washington brass hoped that Pete, if used judiciously, would prove a useful addition to a Senators pitching corps in serious decline from the pennant-winning performance of three seasons earlier. Alternating between the rotation and the bullpen, Appleton vindicated his acquisition, going 14-9, with 12 complete games and a creditable 3.53 ERA for the 1936 season, one that saw the Senators (82-71) post a 15-win improvement over the previous campaign. Unhappily for the DC faithful, neither the Senators nor Appleton would continue the good work, with the 1937 season seeing both the club (73-80) and the pitcher (8-15) headed in the wrong direction. The following two years, Appleton worked primarily in relief, turning in sub-par (7-9 and 5-10) logs for second division Washington teams.

In December 1939, Appleton was a throw-in in the trade that sent hard-hitting Taft Wright to the Chicago White Sox in exchange for outfielder Gee Walker. Appleton was used sparingly by Chicago, going 4-0 with a high 5.62 ERA in 25 relief appearances in 1940. He near reversed that win-loss mark the following season, posting a 0-3 record, with a 5.27 ERA in 13 games. Pete remained on the Sox roster for the 1942 campaign, but was released in early July after pitching less than five meaningless innings. Shortly thereafter, he signed with the St. Louis Browns, going 1-1 with a 2.96 ERA in 14 relief appearances.

Although the 38-year old pitcher was well beyond exposure to the military draft, Pete Appleton then enlisted in the United States Navy, accepting an officer’s commission in November 1942. Like many big leaguers, his military service in World War II consisted mainly of playing baseball on States-side armed forces teams, first with the Navy Pre-Flight nine at Chapel Hill, North Carolina (where Pete also entertained staff and cadets with his musical talents), and thereafter at Naval Air Station Quonset Point in Rhode Island.

On July 3, 1945, Lieutenant JG Peter W. Appleton, now age 41, was honorably discharged from duty. Still reserved to St. Louis, Pete thereupon reported to the Browns. After being hit hard in two relief outings, Appleton was released. Determined to continue his playing career, Appleton then signed with Washington, where one final major-league thrill awaited. On September 8, 1945, he took the mound at Griffith Stadium before President Harry S. Truman, cabinet officials, and more than 20,000 fans and threw a five-hit complete game at the Browns, winning 4-1.12

The spring of 1946 saw Appleton in camp with the Senators, but he drew his unconditional release just before the club headed north. Press friend Shirley Povich informed readers that Appleton was “undecided about his future. He doesn’t want to pitch in the minors and is toying with the idea of jumping to the Mexican League, teaching school, or organizing a band.”13

While making up his mind, Pete returned to his home in Perth Amboy, where, among other things, he could reflect upon a respectable, if unspectacular, major league career. In 14 seasons, he had gone 57-66,14 with a 4.30 ERA in 1,141 innings pitched, striking out 420 batters while walking 486. He had also helped his teams with the bat, hitting .233 in 374 lifetime at-bats.

In time, Pete returned to school, obtaining the credentials needed for a New Jersey teaching certificate from Rutgers University. He also took classes at New Jersey Law School.15 Try as he might, Pete Appleton could not shake baseball from his system. In 1946, he hooked on with the Buffalo Bisons, the Detroit affiliate in the International League, posting a 9-5 record that season, followed by a 7-7 log for the Bisons in 1948. He returned to Buffalo in 1949, but after a single appearance, dropped down to the Sherman-Dennison Twins of the Class B Big State League, going 12-4 in 17 starts. The following year, Pete began his minor-league managing career, taking the helm at Sherman-Dennison in midseason and bringing the Twins (70-78) home in fifth place, all the while continuing to take his turn on the mound. Appleton’s combined 9-10 record for 1949 includes a 1-0 mark in six games for the Dallas Eagles of the Class AA Texas League, as well.

In 1950, Appleton became a full-time manager, guiding the Augusta Tigers of the Class A Sally League to a 66-87 (seventh place) finish. But he proved unable to resist the temptation to insert himself into the action, going 2-2 with a 2.25 ERA in 13 relief appearances for his club. Pete Appleton made his final pitching appearances at age 47, appearing in ten games without a decision for the pennant-winning (85-40) Erie Sailors of the Class C Middle Atlantic League, while being named co-manager of the league all-star team.

In 1952, Pete found himself as non-playing manager for the Roanoke Rapid Jays of the lowly Class D Coastal Plain League. The following season, the Appleton-guided Charlotte Hornets captured the post-season championship of the Class B Tri-State League. The 1954 season saw the Charlotte club and manager Appleton promoted to the Sally League, but with the team languishing at 27-45, Pete was replaced as Hornets manager by Ellis Clary, thus bringing the first phase of his managerial career to a close.

Once again back in Perth Amboy, Pete accepted a baseball scouting position, scouring the East Coast in search of prospects for his old club, the Washington Senators. He also made use of his teaching license, substitute teaching during the offseason. In addition, Pete was a loyal member of the Perth Amboy Elks, actively involved in the affairs of St. Stephen’s parish, and a reliable attendee at NY/NJ Hot Stove gatherings. Perhaps more important, his presence at home lent support to wife Aldona, a rising star on the local political scene and headed for appointment to the bench, becoming in 1958 only the second female state court judge in New Jersey history. All this activity, however, did not ease Pete Appleton’s itch to get back into uniform. And on June 21, 1964, 60-year-old Appleton replaced Jack McKeon (a neighbor from next-door South Amboy, NJ, and decades later, the manager of the 2003 World Champion Florida Marlins) as skipper of the last-place Atlanta Crackers of the International League. At season’s end, Pete surrendered the Atlanta reins, but the following season he was back in harness, albeit only briefly, serving a one-week tour of duty as interim manager of the Wisconsin Rapid Twins of the Class A Midwest League. Appleton’s final managerial stint occurred in 1970 when he returned to Charlotte, replacing Harry Warner at the Hornets helm late in the season.

Between managing assignments, Appleton had remained a scout for the Senators, and thereafter, the Minnesota Twins. In spring 1973, he was placed in charge of the Twins’ minor-league camp in Melbourne, Florida. But soon thereafter, Pete’s health began to deteriorate. Diagnosed with cancer, he was later admitted to St Francis Hospital in Trenton, where he died on January 18, 1974 at age 69. Following a Funeral Mass at St. Stephen’s Church, Pete Appleton was interred at St. Gertrude’s Cemetery in Colonia, New Jersey. Without children, he was survived by wife Aldona, and brothers Joseph, John, and Alex Jablonowski, Jr. Unlike the situation of many who entered the game almost a century ago, baseball was not the only means toward upward mobility available to Peter William Jablonowski/Appleton. Handsome, intelligent, well-educated, and musically talented, he had various career options at his disposal. A life as a journeyman pitcher, minor league manager, and baseball scout was entirely a matter of choice for Pete Appleton. And the game was surely made better because of the path chosen by this honorable and dedicated professional.

Notes

1 The biographical aspects of this profile are derived from material contained in the Pete Appleton file at the Giammati Research Center, Cooperstown, New York; the American League questionnaire completed by Pete Jablonowski around 1930; US census data; obituaries published at the time of Pete Appleton’s death in January 1974, and the writer’s conversations with acquaintances of Pete’s wife, Judge Aldona L. Appleton. Pete’s siblings were Joseph (born 1907), John (born 1910), and Alex Jablonowski, Jr., born 1915.

2 As recounted by sportswriter Fred Lieb in an unidentified March 11, 1933 column preserved in the Appleton file at Cooperstown.

3 As per the American League questionnaire completed by Pete Jablonowski.

4 According to unidentified 1930 newspaper copy contained in the Appleton file.

5 Ray Fisher went 14-5 for the 1919 World Champion Cincinnati Reds and posted a 100-94 record overall in a ten-year major-league career. In 1921, Fisher was blacklisted for accepting the Michigan coaching post after having signed a contract to pitch for the Reds that season. Fisher went on to a distinguished career as Wolverines baseball coach, winning more than 600 games, but remained an MLB outcast until he was restored to good standing by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn in 1980, two years before Fisher’s death at age 95.

6 One Appleton obituary employed the term “jawbreaker” to describe pronunciation of the names of this Wolverines infield trio. See The Sporting News, February 2, 1974.

7 Pete left campus to join Waterbury a few credits short of his degree. He finished his Bachelor of Arts requirements in the offseason and graduated with the University of Michigan Class of 1927.

8 As recounted by sportswriter Gordon Cobbledick in a January 30, 1930 Cleveland Plain Dealer column introducing new Indians acquisition Pete Jablonowski to Cleveland fans.

9 Various conjectures have been proffered for the name change, from Pete deciding that his ethnic surname “was no fit name for the national pastime” (Shirley Povich), to wanting to change his name in order to change his pitching luck (Bill Stern), to the name Jablonowski being an impediment to a future band-leading career (The Sporting News). Bill James, however, places responsibility with Pete’s intended bride who, having already gone through life with one multi-syllabic Polish name (Leszczynski) was unhappy about the prospect of exchanging it for another one. See Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 158. The actual reason why Pete changed his last name at age 29 is uncertain.

10 In his brief time as a Yankee, Pete Appleton’s most memorable experience may have occurred away from the diamond. As recounted by a Ruth biographer, Babe, feeling trapped by his fans, once called a hotel front desk and asked that any Yankees player present in the lobby be sent up to his room. The only one available was the newly acquired Appleton, who then spent the evening playing cards with Ruth, not the party animal of legend, but a lonely and aging ballplayer who simply wanted undemanding company, even if it could only be supplied by a teammate whom he barely knew. See Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974), 1.

11 Washington Post, March 5, 1936.

12 For a fuller account of the game and its attendant pomp, see the Washington Post, September 9, 1945. Pete later described winning the game, his final victory as a major-league pitcher, as “a birthday present for my wife,” according to the Appleton obituary in the Woodbridge (NJ) News-Tribune, January 19, 1974. True enough, the following day (September 9) was Aldona Appleton’s birthday.

13 Washington Post, April 2, 1946.

14 He went 17-19 in 131 major-league games as Pete Jablonowski (1927-1933) and later 40-47 in 210 games as Pete Appleton (1936-1945).

15 As reported in local obituaries published in the New Brunswick Home News and Woodbridge News-Tribune, January 19, 1974.

Full Name

Peter William Appleton

Born

May 20, 1904 at Terryville, CT (USA)

Died

January 18, 1974 at Trenton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.