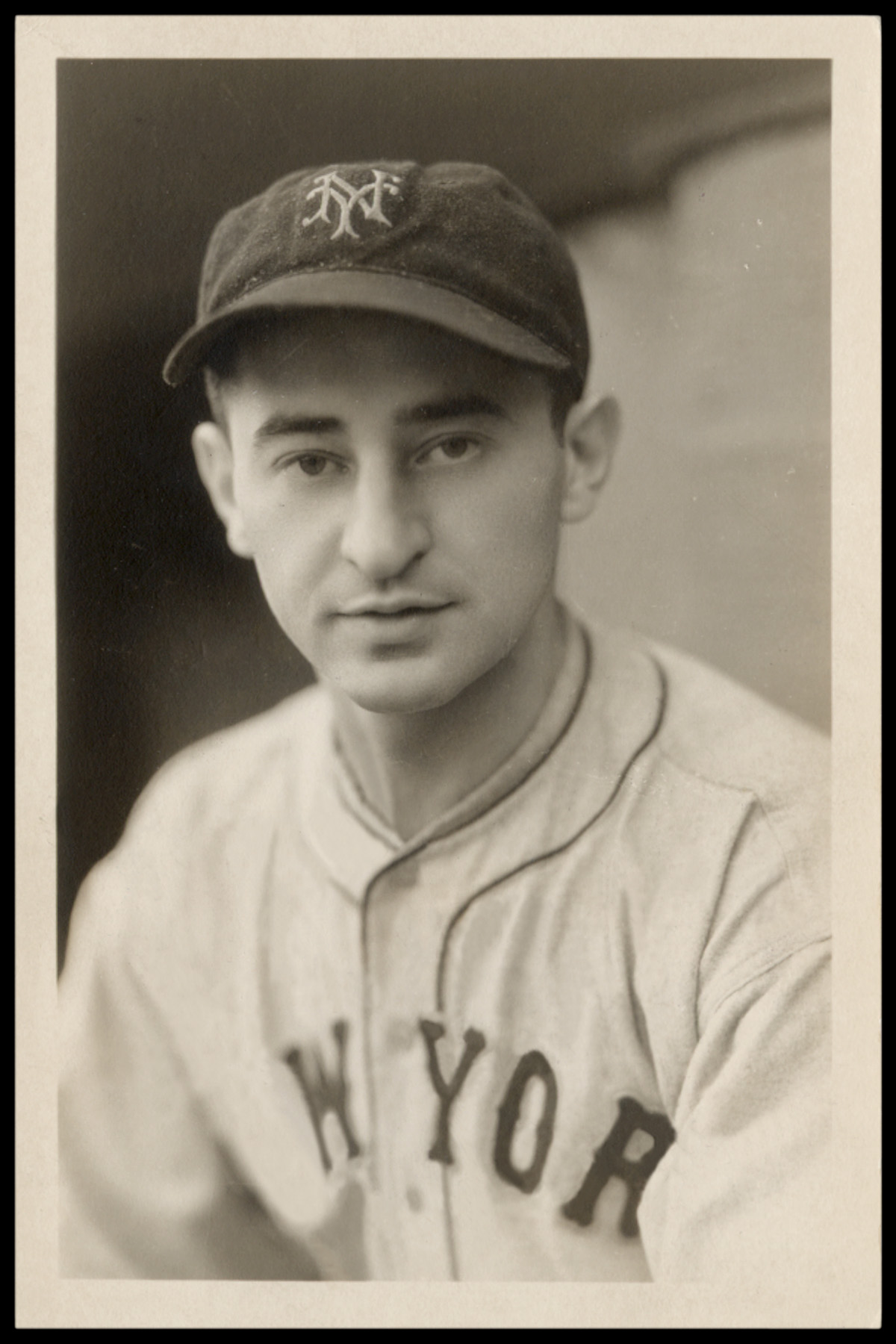

Phil Weintraub

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, great numbers of Eastern European Jews immigrated to the United States, prompting sociologist Edward Ross to comment: “The Hebrews are the polar opposite of our pioneer breed. Not only are they undersized and weak muscled, but they shun bodily activity and are exceedingly sensitive to pain.” In short, according to Ross, Jews would never become full-fledged Americans.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, great numbers of Eastern European Jews immigrated to the United States, prompting sociologist Edward Ross to comment: “The Hebrews are the polar opposite of our pioneer breed. Not only are they undersized and weak muscled, but they shun bodily activity and are exceedingly sensitive to pain.” In short, according to Ross, Jews would never become full-fledged Americans.

Whether intentionally or not, second-generation Americans set out to prove Ross wrong. One of the ways in which they asserted their right to be full-fledged Americans was to become involved in sports, either as athletes or followers. Jewish ballplayers became visible symbols to their fellow Jews of ethnic pride and identity as well as American accomplishment.

This was especially true in New York City, where Jews constituted 30 percent of the city’s population of 5.6 million in the 1920s. The quest for a Jewish baseball player of star status was constantly on the minds of Jewish New Yorkers. It was also on the mind of John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants.

In 1933, a New York youngster named Hank Greenberg was starting what would be a Hall of Fame career, but with the Detroit Tigers.

In the same year, the New York Giants brought up Phil Weintraub from the minors. Weintraub was 25 and had been a professional baseball player since the age of 18.

The saga of Phil Weintraub is a puzzle in a conundrum. For two decades he had a long and tortuous journey through baseball: He played for 13 minor-league teams in addition to the New York Giants, the Cincinnati Reds, and the Philadelphia Phillies. Though he had some fine minor-league seasons, he never seemed to parlay them into a solid major-league career. (Most of his success at the major-league level was attained with the Giants, with whom he had four separate stints.) It wasn’t until 1938, when he was 30 years old, that Weintraub began a seven-year run of playing 100 or more games a season.

Between 1931 and 1945, Weintraub was demoted from the majors or transferred between minor-league teams 20 times. It couldn’t have been for a weak bat: Weintraub’s career batting average in the minors was .337; in the majors it was .295 with 32 home runs and 207 runs batted in. In 1934, playing with Nashville of the Southern Association, he hit .401. (Jimmy Sanders of Martinsville in the Class D Bi-State League led all of organized baseball that year with a batting average of .423.) In the wartime season of 1944, Weintraub hit .316 and drove in 77 runs for the Giants, including 11 in one game, one fewer than the major-league record.

In the wartime seasons of 1944 and 1945, with the major-league talent pool much diluted, Weintraub batted a combined .297 for the Giants. But when World War II ended and major leaguers began to return from military service, Phil was gone from the majors. Age may have been a factor; by that time, he was 38 years old.

A native of Chicago, Phil Weintraub was cultured and dapper. He wore made-to-order suits with the nonchalance of a movie star. He was reported to own one hundred suits. He loved to play the accordion and read. Sportswriter Fred Lieb called him the best-dressed ballplayer in the major leagues. Weintraub may have made the baseball list as one of the best-dressed men, but he couldn’t hold on to a permanent job in the majors.

Weintraub was born on October 12, 1907, to Russian Jewish immigrant parents. His father was in the auction business in Chicago, and wanted Phil to become a partner in the auction trade. (Another source says Weintraub’s father owned a butcher shop.) But Phil sought the life of a professional baseball player. His parents were dead set against it. Ballplayers to them were bums. Doctors, lawyers, professors were their ideas of genuine professions. However, Phil was determined, and his parents gave in.

He briefly attended Loyola University in Chicago, and then in 1926, Weintraub joined the Rock Island, Illinois, club in the Class D Mississippi Valley League as a left-handed pitcher. He soon understood that he wasn’t cut out to be a hurler, but he could hit well.

Weintraub’s professional baseball career was temporarily halted after his brief 1926 season when his father died and he had to take over the auction business. Though he was out of the game, according to the Professional Baseball Player Database, Weintraub was listed on the roster of the Waco club in the Texas League and Danville of the Three-I League in 1927. He returned to baseball in 1931 as a first baseman and outfielder for Dubuque, Iowa, in the Mississippi Valley League. His .372 batting average in 250 at-bats was just two points below the batting champion’s average. Weintraub moved to Terre Haute on the Three-I League in 1931, and he and his teammates were leading the league when it folded, as did many other leagues that year in the midst of the Great Depression. Weintraub hit .323 in 56 games and, after the Three-I League collapsed, played in 54 games for Dayton, Ohio, of the Class A Central League and hit .352. Between his two clubs, Weintraub had 24 doubles, 12 triples, and 9 homers.

In 1933, Phil played for Birmingham of the Southern League, where he hit .296 with 15 home runs and 81 RBIs before making his major-league debut with the Giants late in the season. His first appearance was on September 5. On September 17, he got his first major-league hit, a solo home run. In eight late-season games with the Giants, Weintraub had 3 hits in 15 at-bats.

In 1934, Weintraub went to spring training with the Giants but was sent to Nashville of the Southern Association before the season began. During spring training, Giants manager Bill Terry quashed an anti-Semitic incident. When a Florida hotel refused to register Weintraub and Harry Danning because they were Jewish, Terry threatened to take the entire team elsewhere, and the hotel backed down. When Weintraub was sent back to the minors, Jewish fans in New York inundated the Giants’ front office with mail begging Terry to keep Weintraub with the Giants, but Weintraub remained in Nashville.

Undeterred by his assignment to the minors, Weintraub had a great year, batting a league-leading .401–he was the first player to bat over .400 in the Southern Association in more than 30 years. Weintraub did have an embarrassing moment in one game. The playing field at Sulphur Dell, the Nashville ballpark known to players as “Suffer Hell,” was anything but level. If the right fielder was standing at the base of the fence, he was 22½ feet above the level of the infield. The elevated area was called “the porch.” One day, Weintraub was playing deep and a ball was hit to him. He ran down the porch, and the ball went between his legs to the fence. Phil retreated to the fence, only to see the ball the ball rebound off the fence and again scoot through his legs. Finally corralling the ball, he overthrew the third baseman for his third error on one play.

Called up again by the Giants near the end of the 1934 season, Weintraub appeared in 31 games and batted a healthy .351, with 26 hits in 74 at-bats and 15 RBIs.

No matter how well Weintraub hit, he couldn’t stick with the Giants. After seeing his batting average plunge by 110 points in 1935, to .241 in 112 at-bats, the Giants on December 9, 1935, traded Weintraub and pitcher Roy Parmelee to the St. Louis Cardinals for infielder Burgess Whitehead and cash. Weintraub shuttled between Columbus and Rochester in 1936. Between the two teams, he had his best season at the plate, hitting .361 in 22 games with Columbus and .371 in 115 games with Rochester. In his 137 games with the two teams, Phil smacked out 174 hits, with 37 doubles, 12 triples, and 21 home runs. He drove in 111 runs and scored 108. His .371 mark with Rochester made him a close runner-up for the batting title.

Despite his 1936 batting heroics, Weintraub never played for the Cardinals. Before the 1937 season began, they traded him to the Cincinnati Reds, for whom he played 49 games. Then the Reds sent him back to the Giants. After playing in only six games for New York, Weintraub was shuffled across the Hudson River to the Giants’ Jersey City farm team. There, he hit .269 in 82 games, with 5 home runs and 41 RBIs. In November 1937, the Giants sold his contract to Baltimore of the International League. In 44 games with the Orioles in 1938, Weintraub batted .345, then was purchased by the Philadelphia Phillies in exchange for first baseman Gene Corbett.

There he finally had a chance to show what he had. Playing in 100 games, he hit .311. The Phillies were playing their last season at Baker Bowl in 1938, and Weintraub got the last hit in the old ballpark. The Phils went on to become tenants at Shibe Park.

No matter how well Weintraub performed, he wouldn’t last long at any one major-league club. After his 1938 season with the Phils he was sold to the Boston Red Sox, who sent him to the Minneapolis farm team in the American Association. He played there in 1939 and 1940, batting a solid .331 in 1939 and .347 in 1940, with extra-base power both seasons (36 doubles, 9 triples, a career-high 33 home runs, and a career-high 126 RBIs in 1939; 34 doubles, 4 triples, 27 home runs, 109 RBIs in 1940).

One can’t help wondering why Weintraub was unable to stay in the majors when he proved he could hit. Was he a troublemaker? An unpopular teammate? A guy who didn’t fit into any clubhouse? Or just a victim of the vagaries of baseball? No clear answer emerges.

Retiring briefly after the 1940 season, Weintraub returned in 1941 to play in the Pacific Coast League with the Los Angeles Angels, for whom he hit .302. He spent 1942 with the St. Paul Saints and the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association, and 1943 with Toledo, racking up good numbers for both seasons. With Toledo, Weintraub was the property of the St. Louis Browns.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Weintraub was 34 years old. Called for examination by his draft board in Chicago, he was declared unfit for military service. He could still play baseball, though, and in 1944, the Giants, with their roster depleted by military call-ups, came calling again, drafting Phil off the Toledo roster. At the age of 36, Weintraub was back in the major leagues. In 1944, he appeared in 104 games, batting .316 with 13 home runs and 77 RBIs.

On April 30 of that season, Phil had his greatest day in baseball when he drove in an amazing 11 runs in a game against the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Giants won the game, 26-8. Weintraub had two doubles, a triple, and home run, and a bases-loaded walk, and missed hitting for the cycle because he didn’t hit a single. The 11 RBIs rank him second to Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley and Mark Whiten, who each drove in 12 runs in a game. Babe Ruth, who was at the game, told Phil, “Kid, that was some performance. You knocked in enough runs for a month. Some guys don’t get that many in a season.”

Four weeks earlier, in a preseason exhibition game against the Jersey City Giants at Roosevelt Stadium, Weintraub attracted attention when he caught a ball dropped 400 feet from a blimp from the nearby Lakehurst Naval Air Station.

On June 12, 1944, Weintraub scored 5 runs in a game, one less than the 20th century major-league record held by many players.

Weintraub was back with the Giants in 1945, hitting .272 in 82 games, with 10 homers and 42 RBIs. He also played in 40 games for Newark of the International League, and hit .311 with 8 home runs.

World War II ended that year. Even before the war was over, big-league players had begun to trickle back to their teams, and by the 1946 season they had almost all returned. It was the end of the line for Weintraub, who retired after having played since 1926, though with a four-year hiatus from 1927 to 1930. He said his legs were the primary cause for his retirement.

Weintraub’s fragmented career in the majors included seven years, 444 games, 407 hits, 215 runs, 207 runs batted in, and 32 homers to go with a .295 batting average. (Hank Greenberg’s .313 mark is best among Jewish players.)

After retiring as a player, Weintraub began 1946 as the manager of the Bloomingdale Troopers in the Class D North Atlantic League, but was replaced with the team mired in the standings. Later he was active in the wholesale foods business and then sold real estate in Palm Springs, California. Weintraub was inducted in the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1982.

When he was asked why he had such a limited career in the majors, he gave a vague answer, replying, “I frankly don’t know why I was a minor for so long, but I suppose the final explanation is that is just baseball. It certainly is a strange game.”

Weintraub and his wife, Jeanne, had two children, Phil Jr. and Jill. Phil died on June 21, 1987, at the age of 79, in the Desert Hospital in Palm Springs. He had suffered for four years from lymphoma, but his death was attributed to a heart attack. Survived by his wife and children, he is buried in Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, California.

Although Weintraub’s career fell far short of Hall of Fame status, he could point with pride to two achievements: He embodied the aspirations of Jewish baseball fans in the 1930s and ’40s; and during World War II, he and other players provided a diversion for the American populace during trying times on the home front. Then, when the war ended, they stepped aside for the returning major leaguers.

Sources

Baseball-Almanac.com.

Doyle, Pat. Professional Baseball Player Database, Version 6, Old-Time Data, Inc.

Horvitz, Peter S., and Joachim Horvitz. The Big Book of Jewish Baseball. New York: S.P.I. Books, 2001.

Johnson, Lloyd, ed. The Minor League Register. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1994.

Lee, Bill. The Baseball Necrology. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003.

Levine, Peter. Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jewish Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Minor Leagues Database at SABR.org.

National Baseball of Fame Archives.

Full Name

Philip Weintraub

Born

October 12, 1907 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

June 21, 1987 at Palm Springs, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.