Ryne Sandberg

“What is one to say about June — the time of perfect young summer, the fulfillment of the promise of the earlier months, and with as yet no sign to remind one that its fresh young beauty will ever fade?” — Gertrude Jekyll1

On the afternoon of June 23, 1984, at Wrigley Field, the hometown Chicago Cubs trailed their Midwest rival, the St. Louis Cardinals, 9-8. Young second baseman Ryne Sandberg, already with three hits and four RBIs in the game, led off the bottom of the ninth inning against Cardinals closer Bruce Sutter. “Open up and swing inside,” the right-handed batter said quietly as he stepped into the box. On a 1-and-1 pitch, Sandberg pounced on a sinking splitter and lined it into the last row of the left-field bleachers. Cubs play-by-play announcer Harry Caray bellowed his signature home-run call to WGN Chicago radio listeners — “It might be. It could be. It is! Holy Cow! The game is tied! The game is tied! Ryne Sandberg did it!” Boisterous cheering filled the airwaves for what seemed like an eternity until Caray blurted the obvious: “This crowd is going bananas!”

On the afternoon of June 23, 1984, at Wrigley Field, the hometown Chicago Cubs trailed their Midwest rival, the St. Louis Cardinals, 9-8. Young second baseman Ryne Sandberg, already with three hits and four RBIs in the game, led off the bottom of the ninth inning against Cardinals closer Bruce Sutter. “Open up and swing inside,” the right-handed batter said quietly as he stepped into the box. On a 1-and-1 pitch, Sandberg pounced on a sinking splitter and lined it into the last row of the left-field bleachers. Cubs play-by-play announcer Harry Caray bellowed his signature home-run call to WGN Chicago radio listeners — “It might be. It could be. It is! Holy Cow! The game is tied! The game is tied! Ryne Sandberg did it!” Boisterous cheering filled the airwaves for what seemed like an eternity until Caray blurted the obvious: “This crowd is going bananas!”

The Cardinals struck back with two runs in the top of the 10th, and Sutter returned to the mound to secure the win. With two outs and a man on first, up came Sandberg. Cubs fans rose to their feet, imploring him to achieve the implausible. “Open up and swing inside,” Sandberg reminded himself. As NBC play-by-play announcer Bob Costas began reading the production credits, Sandberg turned on Sutter’s third pitch. “He hits it to deep left-center! Look out! Do you believe it? It’s gone!” Costas exclaimed. Wrigley Field again erupted into a joyful frenzy. The game was tied again.

When the Cubs scored the winning run in the next inning, the outcome was practically anticlimactic. This game on June 23, 1984, would forever be known as The Sandberg Game. Instantly, Ryne Sandberg became a nationally recognized superstar of almost mythic proportions. After the second home run, Costas opined that “Roy Hobbs, The Natural, would be pleased by Sandberg’s performance today.” Later, he drew comparisons to Frank Merriwell, the fictional sports hero from yesteryear. “It is early to start talking MVP,” Costas’s broadcast partner Tony Kubek mused presciently. Reflecting on the game much later, Sandberg wrote, “It was the turning point of my career … it completely changed my life.”2

Sandberg blossomed into a five-tool player, exceptionally rare among middle infielders. Over 14 full seasons and parts of two others, the soft-spoken second baseman compiled a .285 batting average and 282 home runs, collected a Most Valuable Player trophy, seven Silver Slugger and nine Gold Glove Awards, and appeared in 10 All-Star games. In 2001, Bill James ranked Sandberg the seventh best second baseman in major-league history.3 In 2005 Sandberg received the ultimate honor of enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ryne Dee Sandberg was born on September 18, 1959, in Spokane, Washington, the youngest of four children to Derwent “Sandy” Sandberg and his wife, Elizabeth “Libby” (Barter) Sandberg. Sandy and Libby came from very different backgrounds. Sandy was born in Fargo, North Dakota, the son of a Swedish immigrant, and grew up in the small town of Warren, Minnesota. Libby was born in what was then the Belgian Congo, the daughter of a Methodist missionary minister, and grew up in Vermont. Their lives converged during World War II. Through a mutual acquaintance, the two began to correspond while Sandy was overseas serving in the US Army. After the war, a romance flourished. Sandy and Libby were married on September 15, 1946. After Sandy finished mortuary school in Philadelphia in 1947, the couple moved to Spokane.4

Sandy and Libby named their youngest son after New York Yankees pitcher Ryne Duren. “We looked at each other and knew that would be the name if the baby was a boy,“ Libby said.5 Ryne wasn’t the first child in the family to be named after a baseball player. The Sandbergs named their second son after former Philadelphia Phillies Whiz Kid Del Ennis.6 Sister Maryl and oldest brother Lane rounded out the family.

Del, who was five years older, mentored his younger brother until leaving for college. Sandy worked long hours at the Hazen and Jaeger Valley Funeral Home. Libby was a registered nurse and shuttled the kids to school events and practices. Ryne often quoted the no-nonsense wisdom his father imparted: “Keep your mouth shut and eyes and ears open. Then you might learn something.”7

At North Central High School, Ryne excelled in football, basketball, and baseball, and graduated with a 3.2 grade-point average.8 On the gridiron, quarterback and punter Ryne earned All-America Team honors in Parade magazine. During his high-school career (1975-1977), he held the Greater Spokane League record for passing yardage until it was broken by future Super Bowl MVP Mark Rypien three years later.9 On the hardwood, the 6-foot-2 forward received second-team GSL basketball honors his junior and senior years.10 One of his rivals from Gonzaga Prep high school was John Stockton, destined for stardom in the NBA. The late 1970s were a Golden Age of scholastic athletics in the Spokane Valley.

On the baseball diamond, “Berg” (his nickname in high school) was named to the All-City team twice. He hit .417 with 4 home runs and helped lead the Indians to a 25-3 record and second place in the state tournament championship.11 The senior infielder was rated as only the second-best player on the team behind junior catcher Chris Henry.12 Still he drew the attention of major-league scouts.

During his senior year, Sandberg made football recruitment visits to several college campuses, including Big Eight Conference powerhouses Oklahoma and Nebraska. He confided in his high-school coach that he preferred baseball over football. But the pressure of being a local football star weighed on Ryne. He signed a letter of intent to attend Washington State University on a football scholarship. While this caused other scouts to lose interest, Bill Harper of the Philadelphia Phillies was not dissuaded. He and fellow scout Wilbur “Moose” Johnson persuaded Phillies director of scouting Dallas Green to take a flyer on the three-sport athlete.13 On June 8, 1978, Philadelphia selected Sandberg in the 20th round of the amateur draft. Eight days later, Harper met Ryne, his parents, and brother Del at the Sandberg home to present an offer.

“His parents, particularly his mother, were very concerned about Ryne going to college and getting an education,” Harper recalled.14 He made his pitch, which included a $20,000 bonus,15 more in line with a second- or third-round draft choice. Ryne and Del took a walk to discuss the offer. Del had played baseball on the WSU team that went to the 1976 College World Series. He advised Ryne that, if he really wanted to pursue baseball over football, he should sign with the Phils. They returned home and the 18-year-old shortstop inked his first pro baseball contract.

Sandberg’s first stop was Helena, Montana, in the short-season Pioneer League. He batted .311 and was selected by his teammates as their Most Valuable Player in a poll conducted by a local radio station.16 In 1979 he moved up to Class A Spartanburg in the full-season Western Carolinas League, and tied for the team lead in runs scored despite batting just .247. During the season, he married Cindy White, his high-school sweetheart. The teenagers were wed in a civil ceremony attended by some teammates and their manager, Bill Dancy. The marriage lasted 15 years and produced two children, daughter Lindsay and son Justin.

Promoted to Double-A Reading in 1980, Sandberg posted personal bests in virtually every offensive category and was named to the Eastern League All-Star team. After a solid 1981 season at Triple-A Oklahoma City, he was called up to the Phillies and used exclusively as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement. He met his boyhood idol, Pete Rose, and took infield practice with Mike Schmidt and Larry Bowa. Ryne’s major-league debut came on September 2, 1981. In 13 games and six trips to the plate, Sandberg had one hit, a single off Mike Krukow on September 27 at Wrigley Field, using one of Bowa’s bats.17 Over his minor-league apprenticeship, the shortstop showed good speed, defense, and durability, but little power.

On January 27, 1982, Philadelphia traded Sandberg and Bowa to the Chicago Cubs for Iván de Jesús. The oft-told description that Sandberg was a “throw in” to the deal is not entirely accurate. The Phillies seemingly had an abundance of shortstops in the pipeline to succeed the aging Bowa. Right behind Sandberg was Julio Franco, whom Dancy praised as “the best all-around player I’ve seen at this level.”18 At spring training, Bowa said of Sandberg, “he’s a big kid and I hear they might want to try him at third or second. I’m sure they don’t want to get in a box with two outstanding shortstop prospects being ready at the same time.”19 The problem was that the Phillies had Schmidt at third and All-Star Manny Trillo at second, and didn’t see Sandberg as their shortstop of the future.

Sandberg had been offered as trade bait as early as 1980, after his stellar year at Reading.20 Philadelphia redoubled its efforts at the 1981 winter meetings to include him in a package of prospects for front-line pitching help. Ryne was dangled in trade talks with the Blue Jays, Mariners, and White Sox, but nothing came through.21 He reportedly was offered to Milwaukee in a 3-for-1 trade for pitcher Mike Caldwell. When Brewers GM Harry Dalton demanded Franco instead of Sandberg, the Phillies nixed the deal.22

At the end of the winter meetings, it appeared that the Phillies would stick with Bowa for one more season until Franco was ready. However, a salary squabble between Bowa and club President Bill Giles reached an impasse over the holidays.23 Bowa had one year left on his contract and wanted a three-year extension and a big raise. After the new year, Giles began shopping the feisty 36-year-old to teams willing to meet his salary demands.

Green, who had left Philly to become the Cubs general manager, had holes to fill on his new ballclub. He knew that Philadelphia’s trade options were limited. Negotiations between the two clubs intensified. “Gordie [Gordon Goldsberry, director of minor leagues and scouting] kept hounding me not to make the deal unless they included Sandberg,” Green recalled. “It was like pulling teeth to get them to include Sandberg.”24 Finally, the deal was consummated. “It was a group decision [to part with Sandberg],” Phillies vice president and director of player development Jim Baumer said, “but it doesn’t mean everybody agreed.”25 Years later, Giles attempted to make a scapegoat out of Phillies coach Bobby Wine. “Wine had him in winter ball [and] didn’t think he would field well enough to play short or second. And we had Juan Samuel coming up.”26 Wine didn’t appreciate being thrown under the bus, but admitted that “I didn’t think that he could play a quality shortstop like we were used to — like Bowa.”27

“Everyone in our organization looked at [Sandberg] as a utilityman in the majors,” Phils general manager Paul Owens acknowledged.28 Even Sandberg concurred with the deprecation, admitting that “at one point, I was just hoping to be a utility infielder.”29 With Chicago, the 22-year-old was given a shot at a starting position.

At his first Cubs spring training in Mesa, Arizona, in 1982, Sandberg asked equipment manager Yosh Kawano for number 14, which he had worn in high school.30 Unaware of the franchise history (that was Ernie Banks’s number), he was politely given number 23, which he helped transform into an iconic number of its own in Chicago sports.31

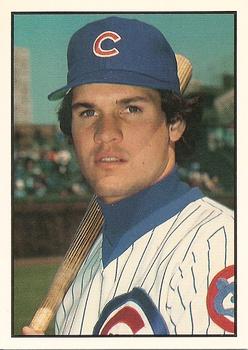

“Sandberg can play any one of three positions for us — second base, third base or center field,” proclaimed manager Lee Elia.32 In his minor-league career, Sandberg had played only four games at third, none in the outfield. He showed enough in Arizona to nail down the third-base job, batting seventh in the 1982 Opening Day lineup. Doing his best impersonation of Willie Mays, Sandberg began his rookie season with just one hit in his first 36 plate appearances.33 Elia never lost faith in his youngster, however, and Sandberg came around. By midseason the freshman was consistently batting first or second in the lineup. His fielding at third was respectable.

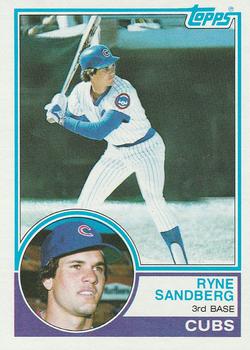

In early September, Green and Elia called Sandberg into the manager’s office. “We picture you as a Bobby Grich-type player [who] can hit .275 or .280 with a little power, steal bases, and score a lot of runs,” Sandberg recalled Green telling him. “We’re going to move you to second base.”34 With almost no preparation, he was relocated from the hot corner to the keystone sack for the remainder of the season. Sandberg finished with a .271 batting average, 7 home runs, 32 stolen bases, and 103 runs scored, a club record for a rookie.35 He polled sixth in Rookie of the Year voting by members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. He was selected to the Topps all-rookie team at third base, a position he never played after 1982.36

Ryne and Cindy relocated from Spokane to the Phoenix area. Soon after their first child was born, the new dad received a phone call from Bowa. The veteran was coming to Arizona before spring training to work out with his new double-play partner. Together they took hundreds of groundballs and polished Sandberg’s pivot at second base. “Larry was always so well-prepared,” Sandberg reflected, “he got me into the pregame routine that I stuck with the rest of my career.”37 The work paid off. In 1983 the second baseman became the first player in the NL to win a Gold Glove Award in his first year at a new position.38

At the plate Sandberg again got off to a slow start, a trademark of his career.39 Eventually the sophomore righted himself and avoided the legendary jinx. He finished the season with a .261 batting average, 8 home runs, 37 stolen bases, and 94 runs scored. Not bad for a punch hitter content with slapping pitches to the opposite field. That approach changed in 1984.

The Cubs were still losing, and Green needed to make changes. He fired Elia late in the 1983 season, and hired ex-Royals manager Jim Frey to be field boss in 1984. Meanwhile, Ryno — the nickname he acquired — emerged as a fan favorite at Wrigley Field. He had the good looks of a matinee idol, fitting for a team that played all of its home games in the afternoon. His quiet demeanor and strong work ethic appealed to the fan base. In February 1984 he signed a six-year contract for $3.85 million through 1989.40

Frey challenged his athletic ex-quarterback in spring training: “How come you’re not more of a power hitter and not an MVP?” Sandberg thought of himself as a table-setter who legged out infield hits and stole bases. “My job with Sandberg was to convince him that he could be that type of player,” Frey said. “It wasn’t so much physical ability as a state of mind and his approach to hitting.”41 Frey worked with his protégé privately in the batting cage for many hours. Sandberg learned to open up and pull the inside pitches that had always given him trouble. Frey began transforming Sandberg into a power threat, as he had done with George Brett years earlier in Kansas City.

On March 27, 1984, Green made the trade that completed the Sandberg metamorphosis, acquiring outfielders Bob Dernier and Gary Matthews from Philadelphia. The trade reunited two Phillies farmhands who had advanced together in the minor leagues. Batting 1-2 in the lineup, the tandem was nicknamed the Daily Double by broadcaster Caray. Matthews hit third behind Sandberg. The combination of the speedy Dernier on base and the clutch Matthews on deck guaranteed that Sandberg saw a lot of fastballs.

After his customary slow start in April, Sandberg began raking the ball. Over the next two months, he posted a .374 batting average and a .630 slugging percentage. He earned NL Player of the Week honors twice, May 7-13 and June 18-24, and Player of the Month in June. His two home runs in The Sandberg Game tallied nine for the year, a new personal best. On June 19 Sandberg was a distant third in fan voting for NL All-Star second baseman, behind Steve Sax and Manny Trillo. When the final ballot count was released on July 6, he topped one million votes to finish first in the category. In the All-Star Game on July 10, Sandberg singled in four at-bats and stole a base. After the break Sandberg resumed his hot hitting. On July 12 he clubbed the only walk-off home run of his career, off Tom Niedenfuer in the bottom of the 10th, to beat the Dodgers. Meanwhile, his fielding at second base was nearly flawless. From June 29 until September 7, Sandberg did not commit an error, a span of 61 games.

After his customary slow start in April, Sandberg began raking the ball. Over the next two months, he posted a .374 batting average and a .630 slugging percentage. He earned NL Player of the Week honors twice, May 7-13 and June 18-24, and Player of the Month in June. His two home runs in The Sandberg Game tallied nine for the year, a new personal best. On June 19 Sandberg was a distant third in fan voting for NL All-Star second baseman, behind Steve Sax and Manny Trillo. When the final ballot count was released on July 6, he topped one million votes to finish first in the category. In the All-Star Game on July 10, Sandberg singled in four at-bats and stole a base. After the break Sandberg resumed his hot hitting. On July 12 he clubbed the only walk-off home run of his career, off Tom Niedenfuer in the bottom of the 10th, to beat the Dodgers. Meanwhile, his fielding at second base was nearly flawless. From June 29 until September 7, Sandberg did not commit an error, a span of 61 games.

Sandberg finished the regular season with 19 round-trippers and elite numbers in many other categories — a .319 batting average (fourth in the NL), .520 slugging (third), 200 hits (second), 36 doubles (tied for third), 19 triples (tied for first), and 331 total bases (second). His 114 runs scored led the league and eclipsed the franchise record set by Billy Herman in 1935.42 For the third year in a row, he swiped more than 30 bases. In the field, he made only six errors. Sandberg’s 8.6 Wins Above Replacement (WAR), calculated by baseball-reference.com, was tops in the National League.

In the NL Championship Series, Sandberg batted .368 with a pair of doubles and stolen bases as the Cubs lost to the San Diego Padres in five games. It was the only disappointment to what was otherwise a storybook season for both the franchise and its star player.

Sandberg collected 22 of 24 possible first-place votes from the BBWAA and easily won the 1984 National League Most Valuable Player Award. He earned his first Silver Slugger and second Gold Glove Award in a poll of managers and coaches conducted by The Sporting News. On January 30, 1985, the baseball field at his alma mater, North Central High School in Spokane, was officially renamed Sandberg Field.43

The Cubs reverted to their losing ways over the next four years. Sandberg, however, continued to shine. In 1985 he finished with 26 home runs and 54 stolen bases, only the third major leaguer to exceed 25 homers and 50 thefts in a season.44 His offensive output fell off slightly the next three years as the Cubs retooled their roster. Even so, the sure-handed gloveman was a mainstay in the Cub lineup. In 1988 he earned his sixth consecutive Gold Glove Award, surpassing the club record of five straight set by Ron Santo from 1964 to 1968.45

On August 8, 1988, the first night game was scheduled at Wrigley Field. As Sandberg stepped to the plate in the bottom of the first, the buxom entertainer known as Morganna the Kissing Bandit vaulted out of the stands and unsuccessfully attempted to smooch Sandberg. On the ensuing pitch, he launched what appeared to be the first Cubs home run ever under the Wrigley lights. Unfortunately for the fans, rain washed out the game and Sandberg’s blast.46

Sandberg entered the final year of his six-year contract in 1989. Even though his $840,000 salary left him well under the five highest-paid second basemen in the game,47 he had refused to renegotiate the deal. However, the 29-year-old was prepared to test the free-agency market if a new pact could not be reached before the first spring-training game. On March 2 his agent and the Cubs agreed to a three-year $6.1 million contract extension that made Sandberg the highest-paid second baseman ever.48

The Cubs were a much different ballclub in 1989 than they were five years earlier in their fairytale season. Green had left the organization, Frey was executive VP in charge of the ballclub, and Don Zimmer was the manager. Sandberg was the only position player left from the 1984 squad. He and 1987 MVP Andre Dawson were counted on to power the offense. But Dawson battled injuries and Sandberg was slow to get untracked. Despite these obstacles, the club remained in the pennant race. On the morning of July 29, the Cubs were 2½ games out of first place and Sandberg was batting just .258 with 12 home runs. Finally, he found his groove. From July 29 through the end of the regular season, Sandberg hit .348 and clubbed 18 round-trippers. Chicago won the NL East Division by six games, and Sandberg’s 30 home runs were a personal best. Moreover, the sure-handed keystone sacker did not commit a fielding error after June 20. In the NL Championship Series, he had eight hits in 20 at-bats, including three doubles, one triple and one home run, but the Cubs fell to the Giants in five games. In end-of-the-year voting, Sandberg collected his fourth Silver Slugger Award and seventh consecutive Gold Glove.

Sandberg had arguably his finest season in 1990. He led the NL with 40 home runs, 116 runs scored, and 344 total bases, all career highs. Sandberg became the first second baseman to have back-to-back 30-plus round-trippers in a season, and was also the first at the position to lead the NL in homers since Rogers Hornsby in 1925. He swiped 25 bases to become the third major leaguer, after Hank Aaron and Jose Canseco, to post at least 40 home runs and 25 stolen bases in a season.49 In the field, Sandberg established a major-league record of 123 consecutive games without an error, topping the previous mark set in 1978 by the Reds’ Joe Morgan.50

Wrigley Field was the site of the 1990 All-Star Game, and Sandberg received 2.26 million votes, the most of any NL player.51 He defended the honor of the host club by winning the Home Run Derby exhibition.52 But the Cubs stumbled from division leader the prior year to a sub-.500 finish.

Sandberg followed 1990 with two solid seasons in 1991 and 1992, blasting 26 homers and scoring over 100 runs in each season. His combined WAR of 21.9 over the three years trailed only Barry Bonds and Cal Ripken, and his fielding remained superb. His cache of awards included his seventh Silver Slugger and ninth Gold Glove, which broke the second-base record of eight held by Bill Mazeroski and Frank White. The player who once aspired to be a utility infielder had developed into a genuine superstar. Sandberg’s handsome physique graced many a magazine cover. National sportswriters mulled over his potential Hall of Fame credentials. Families across the country named their sons after Sandberg . At least two, pitchers Ryne Stanek and Ryne Harper, made it to the major leagues.53 Sandberg was scheduled to earn $2.1 million in 1992, the last year of his three-year deal. Again, his salary had been leapfrogged by other players testing free agency. As before, Ryne set a spring-training deadline to reach a new agreement. On March 2 his agent and Stanton Cook, Cubs chairman of the board, negotiated a four-year, $28.4 million contract extension. The $7.1 million average annual compensation to Sandberg easily exceeded the record $5.8 million-per-season pact given by the Mets to Bobby Bonilla in December 1991.54 Sandberg was the highest-paid major-league player ever.

In 1993 Sandberg hit .309 and was voted to his 10th All-Star Game. But a broken hand suffered in spring training and a dislocated finger in September limited him to 117 games, a career low, and his power output dropped significantly. The following year, Sandberg got off to a decent start but fell into a deep slump. In 27 games from May 12 through June 10, he hit just .194 with one home run.

On June 13, 1994, ten days before the 10th anniversary of The Sandberg Game, the 34-year-old stunned the baseball world by announcing his retirement. In an emotional press conference, with wife Cindy by his side, Sandberg stated that he had lost the competitive fire to play and wanted to spend time at home with his teenage children. “I lost the edge that it takes to play — the drive, the motivation, the killer instinct,” he admitted, forfeiting approximately $15 million left on his contract.55

In his autobiography published in 1995, the formerly quiet Sandberg expanded on his frustration. He criticized the Cubs management, particularly Larry Himes, who had replaced Frey as general manager, for allowing Dawson and pitcher Greg Maddux to leave as free agents. Without naming names, he lambasted the younger players who he said seemed more interested in individual stats than team success.56

The reclusive star insisted that marriage difficulties had not influenced his decision to leave the game. An NBC Nightly News segment broadcast on July 11, 1994, depicted a happy Sandberg family frolicking in the backyard pool.57 Subsequently, it was reported that Cindy had filed for divorce in December 1993. After a brief reconciliation over Christmas, Cindy renewed the filing one week after Ryne’s retirement. On July 5, 1995, the divorce became official as the couple agreed to joint custody of their children. On August 19, 1995, Ryne married Margaret Koehnemann, the mother of three children from a previous marriage.58

With his personal life in order, and Himes gone, Sandberg ended his retirement and returned to the Cubs for two seasons. He signed a one-year deal for $2 million, plus incentives, in 1996 and bashed 25 home runs and drove in 92 runs.59 Sandberg re-signed for $3.25 million in 1997 with a vesting option for a second year.60 On April 26, he slugged his 267th career home run, breaking the major-league record for second basemen set by Morgan.61 But his production dropped off, and on August 2 Sandberg announced he would retire at the end of the season. He stroked his final career home run on September 19, 1997, one day after his 38th birthday. The following afternoon, the Cubs held Ryne Sandberg Day. “I truly lived my field of dreams right here at Wrigley Field,” he told the sellout crowd.62 Sandberg remained with the Cubs organization as a spring-training instructor for nine years.

In 2005, his third year of eligibility, Sandberg was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame with fellow infielder Wade Boggs. The honor was not without some hullabaloo. Joe Morgan, elected to Cooperstown in 1990, had questioned Sandberg’s legitimacy after his first retirement in 1994, telling BBWAA Secretary Jack Lang, “He was kind of quiet, and his teams never won anything. He never showed me that kind of leadership. When things are going bad, you don’t just walk away, do you?”63 Morgan did not attend Sandberg’s induction ceremony due to family commitments, which some viewed as a further snub.

“This will come as a shock, I know, but I am almost speechless,” the self-effacing Sandberg joked in his induction speech. He went on to state that “learning how to bunt and hit and run and turning two is more important than knowing where to find the little red light at the dugout camera,” a not-so-veiled swipe at former teammate Sammy Sosa. At the conclusion of his remarks, the newly outspoken inductee addressed the steroid scandal, saying, “Respect for the game of baseball. It’s something I hope we see again.”64 On August 28, 2005, Sandberg became the fourth Cubs player to have his number retired, joining Banks, Billy Williams, and Santo.

In 2007 the Hall of Famer returned to the minors and began a new chapter in his baseball career. Sandberg was hired by the Cubs to manage the Peoria Chiefs of the Class A Midwest League. Two years later he moved up to the Double-A Tennessee Smokies, and in 2010 was promoted to the Triple-A Iowa Cubs, where he earned Pacific Coast League Manager of the Year honors. He interviewed for the Chicago manager position vacated by Lou Piniella, but did not get the job. Rather than remain in Iowa, Sandberg transferred to the Philadelphia organization that originally signed him, and piloted the Triple-A Lehigh Valley Iron Pigs for two seasons. On August 16, 2013, the Phillies fired Charlie Manuel and signed their former farmhand to a three-year managerial contract. After posting a 119-159 record in Philadelphia over three seasons, the skipper resigned on June 25, 2015, amid a front-office shakeup.

Sandberg returned to the Chicago organization in the role of ambassador, greeting season-ticket holders and attending charity events on behalf of the ballclub. It was a fitting honor for one of the greatest and most popular players in club history. On October 30, 2016, Sandberg finally got to a World Series with the Cubs, tossing out the ceremonial first pitch at Wrigley Field before Game Five. As of 2019 he and Margaret resided in the Chicago suburb of Lake Bluff, Illinois. He is a frequent Cubs commentator on local cable TV and radio broadcasts.

Last revised: September 10, 2019

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank SABR member Bob Webster for the loan of several books from his personal library, and William Christ and Bob Webster for their valued critique of this work.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Phone interviews with Del Sandberg, April 19 and June 3, 2019.

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Ryne Sandberg; Cooperstown

Metropolitan Library System; Oklahoma City University Libraries; University of Washington Library, Seattle.

Baseball Almanac (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America 2006-2011).

Baseball Guide (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1979-2005).

Colletti, Ned. You Gotta Have Heart (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Publications, 1985).

Gentile, Derek. The Complete Chicago Cubs: The Total Encyclopedia of the Team (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2002).

Gold, Eddie, and Art Ahrens. The New Era Cubs 1941-1985 (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1985).

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

Masterson, Dave, and Timm Boyle. Baseball’s Best: the MVP’s (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1985).

Milton, Steve, ed. The Baseball Game I’ll Never Forget (Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly Books, 2018).

Sandberg, Ryne, with Fred Mitchell. Ryno! (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1985).

Sandberg, Ryne, with Barry Rozner. Second to Home: Ryne Sandberg Opens Up (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1995).

Notes

1 Gertrude Jekyll, Wood and Garden: Notes and Thoughts, Practical and Critical, of a Working Amateur (Salem, New Hampshire: The Ayer Company, 1983), 77.

2 All quotes from Ryne Sandberg about The Sandberg game were from Ryne Sandberg, as told to Barry Rozner, November 2012, The Baseball Game I’ll Never Forget (Buffalo: Firefly Books, 2018), 60-61.

3 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 490.

4 geni.com and phone interview with Del Sandberg, April 19, 2019.

5 Steve Rushin, “City of Stars,” Sports Illustrated, July 27, 1992: 65. Sandberg offered two versions of the source of their inspiration, both of which seem to be erroneous. Early in his career, he was quoted saying that when his mother was pregnant, his father took her to see the Yankees play in Minnesota, and Ryne Duren pitched a one-hitter. The Yankees did not play in Minnesota until 1961. Duren did pitch a three-hit shutout as a member of the Denver Bears, the Yankees’ Triple-A farm club, in a playoff game against the Minneapolis Millers on September 11, 1957, two years before Sandberg was born. Later, Sandberg wrote that his parents saw Duren pitch for the Yankees in the 1958 World Series, 11 months before he was born and certainly before Elizabeth was pregnant. Perhaps an amalgam of both events influenced his parents’ decision. Sandberg also wrote that his middle name, Dee, is a shortened form of Duren.

6 Del Sandberg is the father, and Ryne Sandberg an uncle, of Jared Sandberg, who played for the Tampa Bay Devil Rays from 2001 to 2003.

7 Jerome Holtzman, “Sandberg Adjusts Focus to Recovering,” Chicago Tribune, 4, 2.

8 John Blanchette, “At His Alma Mater, Sandberg Had a Field Day,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, January 31, 1985: 19.

9 Vince Grippi, “Yardage Absurd for Brett Rypien,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, October 6, 2013: C-3.

11 Vince Grippi, “Sandberg Led Quietly,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, January 5, 2005: C-6.

12 Chris Henry was drafted by the Seattle Mariners in the 10th Round of the 1979 amateur draft and played in the minor leagues from 1979 to 1982. His career ended after an elbow injury.

13 Jeff Schuler, “Following His Heart,” Allentown Morning Call, February 26, 2012, 8.

14 Ibid.

15 Brad Fuqua, “Harper: Phillies Scout for life,” Corvallis (Oregon) Gazette-Times, October 4, 2012.

16 Marty Mouat, “Phillie Shorts,” Helena (Montana) Independent Record, August 27, 1978: 7.

17 Schuler.

18 Bill Conlin, “Phillies Add Class A Shortstop,” Philadelphia Daily News, October 30, 1980: 70.

19 Conlin, “Bowa Won’t Whine over Earnest Julio,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 13, 1981: 78.

20 Jayson Stark, “Phillies, Brewers Talk Trade,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 10, 1980: C-5.

21 Stark, “Six-Player Offer Fails to Land Phils a Pitcher,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 12, 1981: C-5.

22 Hal Bodley, “Phils Disgusted; Deals Collapse,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1982: 38.

23 Frank Dolson, “Bowa Doing a Not-So-Slow Burn About Phillies’ Breach Of Faith,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 23, 1981: D-1.

24 Robert Markus, “Sandberg Play at 2d Is Pivotal to Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, March 13, 1983: 8-4.

25 Jerome Holtzman, “Wine’s Taste Poor,” Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1984, 4-3.

26 Ibid.

27 Holtzman, “The Talk’s Good at Wrigley, Too,” Chicago Tribune, August 21, 1984: 4-2.

28 Goddard, “Call Him ‘Kid Natural,’” TSN, August 20, 1984, 3.

29 Kelly Thesler, “Cubs Immortalize Sandberg’s No. 23,” MLB.com, August 28, 2005. The Phillies traded Franco, their shortstop of the future, one year later and would lack stability at the position for two decades. Franco played 23 major-league seasons and amassed 43.5 career Wins Above Replacement. Samuel played 16 seasons and compiled 17.0 career WAR. Their combined career WAR is less than the 68.0 career WAR achieved by Sandberg. Source: baseball-reference.com.

30 Ibid.

31 On June 19, 1984, four days before The Sandberg Game, the Chicago Bulls of the NBA drafted Michael Jordan. He also wore the number 23.

32 Holtzman, “DeJesus [sic] Traded for Bowa, Rookie,” Chicago Tribune, January 28, 1982: 4-7.

33 As a rookie in 1951, Mays had but one hit in his first 32 plate appearances.

34 Sandberg with Rozner, Second to Home, 40.

35 Goddard, “Cubs Slash Staff; $2 Million Deficit,” TSN, October 18, 1982: 30.

36 Patrick Reusse, “Gaetti Winters in Twin Cities,” TSN, December 6, 1982: 53.

37 Tom Housenick, “Sandberg vs. Elway? It Might’ve Happened … And More About a Young Ryne Sandberg,” blogs.mcall.com/ironpigs/2012/02/sandberg-vs-elway-it-mightve-happened-and-more-about-a-young-ryne-sandberg.html, February 26, 2012.

38 Debbie Becker, “Ryne Sandberg, He’s Keeping Cubs Hot, Making Cellar Bearable,” USA Today, August 14, 1986.

39 Sandberg posted a lifetime OPS (On Base Average plus slugging average) of just .660 in April, compared with .816 for all other months. Source: retrosheet.org.

40 Phil Hersh, “Sandberg for Real? Naturally,” Chicago Tribune, July 8, 1984: 4-13.

41 Carrie Muskat, comp., Banks to Sandberg to Grace: Five Decades of Love and Frustration with the Chicago Cubs (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2001), 185.

42 Goddard, “Hard Work, Improvement Bring Sandberg Top Award,” TSN, December 10, 1984: 48.

43 Blanchette.

44 The first two players were Joe Morgan (1973, 1976) and César Cedeño (1973, 1974). Dave van Dyck, “Sutcliffe Eases Mind for the Winter,” TSN, October 14, 1985: 24.

45 Van Dyck, “Frey Likes the Hand He Has,” TSN, December 16, 1985: 49.

46 Holtzman, “Lights! Action! And then …,” Chicago Tribune, August 9, 1988: 4.

47 N.L. Notebook, TSN, February 6, 1989: 30.

48 Alan Solomon, “Sandberg Richest 2d Baseman,” Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1989: 2-1.

49 “A Season of Surprises,” TSN, October 15, 1990: 14.

50 Sandberg’s major-league record, set over the 1989-1990 seasons, was broken in 2007 by Luis Castillo of the Minnesota Twins. His NL mark was bested in 2012 by the Cubs’ Darwin Barney, who had played for Sandberg in the Cubs minor-league organization.

51 “N.L. Notebook,” TSN, July 16, 1990: 9.

52 Andrea Zani, “All-Unpopular: Canseco, Strawberry Earn Honors,” TSN, July 23, 1990: 21.

53 Marc Topkin, “Snell Impresses with His Positive Outlook,” Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida), May 15, 2017: 4C; “Insell Is Picked for National Hall,” Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), March 17, 2007: 10C.

54 Tim Kurkjian, “Rolling a 7,” Sports Illustrated, March 16, 1992: 35. The contract called for a $3.5 million signing bonus, annual salaries that topped out at $7.1 million in 1996, and a club option in 1997 with a $2.5 million buyout.

55 Steve Marantz, “Light Footprints in the Sand,” TSN, June 27, 1994: 16.

56 Sandberg’s allegation was supported by comments attributed to Cubs manager Jim Lefebvre. See “N.L. East,” TSN, September 6, 1993: 20.

57 John Sheehe, “Ryne Sandberg piece NBC News 1994,” published January 23, 2014, youtube.com/watch?v=lU6cnwiJKi4.

58 Fred Mitchell, “With New Love in Life, Ryno Returns to 1st Love,” Chicago Tribune, October 31, 1995: 4-7.

59 Rob Rains, “New Life Gives Sandberg Renewed Look at His Cubs,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, November 8-14, 1995: 20.

60 Rozner, “N.L.,” TSN, December 9, 1996: 14.

61 Sandberg’s record was broken in 2005 by Jeff Kent.

62 Bill Jauss, “Ryne Thanks Fans for ‘Field of Dreams,’” Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1997: 3-3.

63 Jack O’Connell, “Detour on Road to Hall,” Hartford Courant, June 19, 1994: E12.

64 Ryne Sandberg Induction Speech transcript, player file, Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Ryne Dee Sandberg

Born

September 18, 1959 at Spokane, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.