1951 Giants: The Shot’s Long Shadow

This article was written by David H. Lippman

This article was published in 1951 New York Giants essays

I don’t know how he got hold of me. Probably it was through my membership in the Society for American Baseball Research, which has “New York/San Francisco Giants” and “New York Yankees” listed as my interests. It might have been from Alan Blumkin, the SABR trivia king.

I don’t know how he got hold of me. Probably it was through my membership in the Society for American Baseball Research, which has “New York/San Francisco Giants” and “New York Yankees” listed as my interests. It might have been from Alan Blumkin, the SABR trivia king.

But sometime in 1998 or 1999, I got a call from a Brooklyn artist named Stuart Leeds, who was a Giants fan growing up, and he’d heard I loved the Giants, and wanted me to help him get a New York Giants club off the ground.

I was happy to do it. The Giants are a big part of my family history. My grandfather, Joe Lippman, was introduced to baseball in general and the Giants in particular in 1908, when his older brother, Sam, took Grandpa to see Christy Mathewson fire a 3-0 shutout at the Cincinnati Reds. Grandpa was hooked.

To add to the linkage, Sam worked in the pool hall Giants manager John McGraw owned with the notorious gambler Arnold Rothstein, emptying spittoons. That enabled Grandpa to actually meet guys like McGraw and Mathewson, and attend games like “Merkle’s Boner” and the World Series games the Giants played, through 1924.

Sam moved up in the Rothstein organization to become a bagman and enforcer. Grandpa moved up through Fordham University to become a pharmacist. Sam skimmed the take from Rothstein for unknown reasons. Grandpa had a hard time keeping the pharmacy afloat in the Great Depression. Sam was whacked and is a cornerstone in the Triborough Bridge. Grandpa died in 1975 in his sleep in a Florida retirement community. But his two teams were the Giants and the Yankees, as were my father’s.

Unlike millions of other Giants (and Dodgers) fans, neither Grandpa nor Dad claimed to have been present when Bobby Thomson unloaded his historic shot. Dad was in the Army in California, getting ready to ship out to the Korean War. Grandpa was running his pharmacy in Washington Heights, listening to Russ Hodges.

When the Giants moved to San Francisco, Dad and Mom went out there too, Dad working for an advertising agency, so he didn’t have the separation problems. He had a bigger one in 1962, with his two favorite teams facing off in the World Series, and me about to be born. The Giants lost the World Series, Kennedy got those missiles out of Cuba, Richard Nixon was predicted to lose the California governor’s race, and Mom went into labor minutes later, and I showed up late the next day.

Thirty-seven years later, it was time to honor Grandpa’s and Dad’s favorite team and legacy by putting together the Giants club and doing their newsletter. So I did. And we put together a lunch for like-minded folks to honor Bobby Thomson himself at Forlini’s, an extremely popular restaurant near the courthouse complex in lower Manhattan. For decades, cops, assistant district attorneys, defense lawyers, and their high-priced clientele have hung out there after work, swirling drinks, exchanging gossip, and eating terrific pasta. It was the perfect place to honor someone who was central to New York’s sports history.

We sent out the invites, contacted Bobby, who was delighted to come.

We arranged his transportation, and booked the restaurant for an October Saturday luncheon close to the actual 50th anniversary. The San Francisco Giants were generous enough to send us posters they gave away to fans about the home run, which included reprints of historic Willard Mullin cartoons of the pennant race’s final weeks and days, depicting the famed Dodger “Bum” and the mountainous Giant. It’s sad nobody uses those characters any more.

Then we ran into some trouble. First, Bobby’s wife, Winkie, died. Then his son, Bobby Jr. I thought about how the Giants had a history of bad luck, most of which Grandpa had seen, from Merkle’s Boner in 1908 to Hank Gowdy tripping on his mask in 1924 to lose that World Series. And in 2001 they were amid a 50-year drought between world championships.

The bad luck bottomed out on September 11, 2001, and when I made my way to the luncheon the next month, lower Manhattan’s streets were cordoned off by National Guardsmen wearing Kevlar helmets and clutching automatic rifles. Gritty ash and smoke still covered buildings, and walls were festooned with posters depicting people who had gone “missing” in the World Trade Center’s destruction, asking the public to help find them. Baseball didn’t seem so important, yet at the same time, it seemed more important than ever … a symbol of determination and resilience amid tragedy.

As I approached the restaurant, there was Bobby himself, with a friend, about to enter.

“I guess this is the place,” the friend said.

“I think so,” Bobby answered, pointing out someone going in who was wearing a New York Giants jacket. “He looks like one of us.”

I introduced myself and told Bobby this was the place, and held the door open. The Staten Island Scot entered Forlini’s and the group of people there turned, saw him, recognized him, and burst into applause.

Being one of the people who organized the event, I got to sit at the head table, and was called upon to deliver remarks. Fortunately someone taped the event for posterity, so I have them.

Before we did the ceremonial stuff, though, we had lunch, and I started off by amusing Bobby by requesting the inevitable autographs on various books about the Giants, including my battered 1984 Giants yearbook, which was themed to honor the team’s All-Stars over the years, as the Giants hosted the All-Star Game that year. It’s also signed by Jo-Jo Moore, Harry Danning, and Monte Irvin.

Bobby was interested in the yearbook, and flipped through it. He recognized teammates and opponents, and didn’t seem to realize just how many All-Stars the Giants had in their history.

After that, over lunch, we talked. What did he think of today’s salaries? Immense. He shook his head. What did he think of today’s players? They were good. He didn’t watch the game that much, but he liked what he saw. One difference was how ballplayers looked physically bigger. They did more weight training now, often year-round. In his day, Bobby said, they’d do some calisthenics before games, and that was about it. In the offseason, nothing.

I asked Bobby who was the toughest pitcher he’d ever faced. “Ewell Blackwell,” he responded swiftly. I agreed that a lot of people would agree that the “Eel” was pretty tough.

Then it was time for the ceremonies. We sang the Giants’ old theme song from the 1950s, “We’re Calling All Fans, All You Giant Ball Fans.”

Stu Leeds had to talk, as president. Attendees gave their memories of where they were when Bobby hit the shot — most, like Grandpa, heard Russ Hodges screaming his head off on the radio.

Then came my turn. I had my notes prepared. Having spent the last few years being a Navy TV and radio broadcaster, I had no problem with public speaking and prepared my words. Being in love with the sound of my own voice, I always had lengthy speeches.

First I took care of the pleasantries … thanking everyone for coming, thanking the event organizers for doing their jobs, thanking Forlini’s for the food.

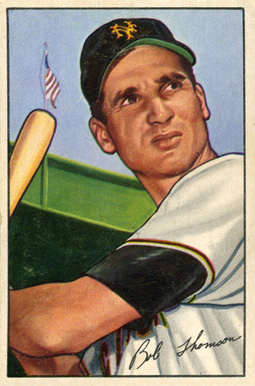

Then I talked about Bobby Thomson’s life and career. I pointed out that my father had watched Giants games in the late 1940s from the Polo Grounds bleachers, when the team had great hitting and no pitching. Dad remembered Bobby Thomson not as much for the great home run, but for being a steady bat and RBI presence in the team’s batting order.

I also pointed out that he had done something more important than play for the Giants: he had served our country in time of war, as a member of the US Army Air Force in World War II, and thanked him as a fellow veteran for that.

Then I noted that Bobby had also distinguished himself as a businessman and community member, and noted that he had suffered the losses of his son and wife in the same year, and extended condolences on behalf of the entire club to him on that.

Finally, I discussed the history and pain that hung over this luncheon: that the Lower Manhattan surrounding us had recently been the target of a horrific terrorist attack that had killed thousands of our fellow New Yorkers, and torn out our hearts. However, like the Giants of 50 years ago, our entire city and region was resilient, would refuse to give up in the face of this attack, and would rise to victory.

Applause came from all around, and I returned to my seat.

Bobby now rose and delivered his remarks. He started off spontaneously, thanking us for our words and mine. He was grateful for the thanks for his military service and the condolences. He enjoyed his years in baseball, particularly with the Giants, and felt the love and loyalty of Giants fans.

After that, he recounted the famous home run. It sounded slightly rehearsed, but I remembered that Bobby had been giving the account of this particular at-bat for the past 50 years, and there wasn’t much more he could say about it anymore.

He told us how he was very irritated at having a horrible day at the plate and in the field, and wanted to do something positive, and was beating himself up as he came to bat. After the first pitch from Ralph Branca, Thomson said he was sure Branca would throw another fastball. Later he would admit that he knew that such was the case, but not this afternoon.

Thomson described the home run — running around the bases as if he were gliding on air — fans cheering, his teammates gathering at home plate, and thundering into the happy throng when he completed the circuit. Self-effacing to the end, Thomson admitted that if he were a better hitter he would have taken the critical pitch – it was a ball.

The evening of the home run, he’d appeared on the Perry Como show, where he sang a jingle for the Giants’ radio sponsor, Chesterfield cigarettes, before a live audience. I marveled at that — ballplayers still do late-night TV shows, still make commercial endorsements, and still hit pennant-winning home runs, but not for cigarettes anymore.

After the Como show, Thomson took a taxi home to Staten Island, where his older brother, Jim, asked, “Do you realize what you did?” Thomson found the question silly. He’d won a pennant and the three RBIs on the homer gave him a 100-RBI season, an important negotiating point for his 1952 contract.

“No, you don’t see it,” Jim said. “That might never happen again.” And then Bobby Thomson realized how important the home run had been to the American psyche. At the luncheon he finished up by saying again how humbled he was to be honored by the fans there, because “baseball is a wonderful game.”

We gave him a check as an honorarium, and he was going to give it to a Little League program he supported through his church, but Stu Leeds said, “No, this is for you.”

“Don’t spend it all in one place,” I added, for gag value.

Then a boombox played the now familiar tape of Russ Hodges’ broadcast, and Bobby smiled, and said, “Who is that guy?”

After that, everybody headed in their various directions home.

Bobby moved down to South Carolina sometime after that, and died on August 16, 2010. Two months later, the Giants won their first World Series since 1954, and did so again in 2012 and 2014, going from a semi-forgotten and jinxed team playing before empty seats in a windy mausoleum to a baseball powerhouse.

There’s an irony in how New Yorkers have mostly forgotten the Giants, but still worship the Brooklyn Dodgers. When the San Francisco Giants won their three Series, they brought the immense world championship trophy to New York, booked a hotel, and held breakfasts for Giants fan clubs and expatriate San Franciscans to celebrate the victory, bringing along their ownership and Willie Mays himself — frail but alert — to talk to the fans. The Dodgers, I point out, have not seen fit to do so — even though one can argue that Citi Field provides them with a second home ballpark.

I missed the Giants’ 2010 event due to a work commitment, but made the 2012 and 2014 celebrations.

At both I took time to deliver a recruiting pitch for upcoming SABR events, thanked Willie for serving in the armed forces in time of war (audience reaction was two seconds of stunned silence, followed by lengthy applause), and asked him who was the best defensive center fielder he ever saw, besides himself.

Willie, diplomatic to the end, evaded the question, but left a hint that he thought it was Ken Griffey Jr. Good choice, I noted.

Someone else asked Willie how he would have fared if Bobby Thomson had been walked — intentionally or otherwise — in the critical game in 1951. Willie expressed relief at not having to come to bat in that situation. He’d not been hitting well down the stretch, and was grateful that a veteran like Thomson was batting in that situation. I was struck by this dose of humility from a titan like Mays. It was a generous and truthful statement.

Grandpa was also a man who didn’t tell lies. Unlike many Giants fans, he did not say he was at the game. He had a drugstore to run. He heard Russ Hodges give his hysterical account of the home run, and cheered and roared over it.

The next day he talked with his brother-in-law, Frank Denker, who ran a drugstore in Brooklyn. Frank was, of course, a Dodgers fan, and he’d listened to Red Barber’s account of the game. Grandpa recounted Hodges’ version and Frank told Grandpa that Barber had simply said, “It’s in there for the pennant!” and then shut up, trained not to talk against a crowd.

When Barber went back on the air, he tried to console Dodgers fans by giving that week’s American casualty bill for the endless, grinding Korean War. The grim number (about 150 dead) gave Grandpa a pause amid the celebrations.

At the time, Dad was an Army corporal in Fort Lewis, Washington, waiting to board a troopship to take him to Korea and service up the line. Dad went to Korea and Item Company of the 31st Infantry two weeks later. Some months later, half of his company would be killed in a failed attack on “Jane Russell Hill.” It would only take Dad 40 years to talk to me about it.

Russ gave the home run glory. Red put it in perspective. Fifty years later, as we celebrated the home run amid the aftershocks of 9/11, I saw the value of both broadcasts.

DAVID H. LIPPMAN is a 35-year veteran journalist with experience in newspapers, wire services, TV, radio, public relations, on three continents: North America, Asia, and Oceania. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Journalism from New York University and Master of Fine Arts Degree in Creative Writing from the New School for Social Research. He has won numerous awards for journalism in daily newspaper work. Has served for the past 17 years as a Press Information Officer with City of Newark, NJ, under four mayors, and writes articles on World War II for “World War II History” magazine, and recently published an e-book on World War II. He is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research, and serves on its BioProject, Games, Black Sox, and Media Committees.