Harry Frazee and the Red Sox

This article was written by Matthew Levitt - Mark Armour - Daniel R. Levitt

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 37, in 2008.

When the Boston Red Sox won the World Series in 1918, it was their fifth triumph in the fifteen years of the modern classic. The club had the best player in baseball, outfielder-pitcher Babe Ruth, another top hitter in Harry Hooper, star catcher Wally Schang, and four other pitching stars — Carl Mays, Dutch Leonard, Joe Bush, and Sam Jones. All were younger than 27. With the ending of the Great War, Ernie Shore, Duffy Lewis, and other stars were returning from military service. Local fans were optimistic — not only because the ballclub was loaded with talent but because Bostonians had become accustomed to great teams since the early days of professional baseball.

Within a few years all of the above players were gone, mostly traded or sold to the New York Yankees, and the Red Sox had become a laughable franchise, finishing dead last in nine of eleven years from 1922 through 1932. The Yankees, Boston’s previously irrelevant neighbor to the south, took advantage of the Red Sox largesse to build a dynasty, winning their first-ever pennant in 1921 and going on to win a total of 29 in a 44-year period.

The man who owned the Red Sox and presided over this change of fortunes was Harry Frazee. Frazee, a New York based theater owner, producer and director, bought the two-time defending champions after the 1916 season, then oversaw another championship in the war-ravaged 1918 season. After divesting himself of all of his best players, the team he sold to Bob Quinn in 1923 was a wreck, and he soon took his place as one of the more vilified people in Boston’s 85-year championship drought. As recounted in Fred Lieb’s 1947 team history, The Boston Red Sox, Frazee dismantled his team because he needed money to help finance his plays — when he didn’t have any players left to sell, he bailed out and sold the entire team.1 This depiction of Frazee and the team’s dismantling was prevalent throughout most of the twentieth century.

In 2000, Glenn Stout and Richard Johnson published their book Red Sox Century, which famously revised the Frazee story2. According to their version, and several subsequent articles written by Stout3, Frazee was not a villain, but a victim. He was in no way short of money — in fact, he was a wealthy man throughout his years in baseball, and he died rich.

Why was Frazee a victim? According to Stout and Johnson, Frazee was being actively forced out of his position by American League president Ban Johnson, and many of Johnson’s allies would not trade with Frazee. One team that would was the Yankees, and, all things considered, Frazee made good deals that turned out poorly because of some unforeseen bad luck.

Why did Johnson want Frazee out in Boston? Mainly, according to Stout, because Johnson hated Jews, and he believed Frazee was Jewish. Frazee wasn’t, but he made his money in an industry where Jews played a prominent role, and that Frazee was Jewish was suggested in at least one published story. Fred Lieb, according to Stout, was also anti-Semitic and for that reason revived the anti-Frazee angle in 1947.

This article will show that the Stout/Johnson thesis is almost completely false. Fred Lieb was not a historian in the way we think of baseball historians today. He was a baseball reporter and storyteller who lived through many of these events, and his books are filled with (mostly small) errors due to his reliance on memory, either his or someone else’s. But Lieb got the Frazee story right, and recent attempts to change history are misguided and a disservice to the historical record. The Harry Frazee Papers, recently available at the University of Texas,4 and New York Yankees business and financial records on file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum make clear both Frazee’s financial distress and the large dollar amounts involved in his player transactions with the Yankees. Harry Frazee sold Babe Ruth and several other players (before and after the Ruth sale) to the Yankees for upward of $450,000 because he needed the money.

BRIEF SUCCESS IN BOSTON

Harry Frazee and theater pal Hugh Ward purchased the Red Sox along with Fenway Park in November 1916 from Joseph Lannin for a total capital obligation of $1,000,000. The duo paid $662,000 for the club itself: $400,000 in cash to Lannin (of which Lannin used $100,000 to repay outstanding loans to parties from whom he had purchased the club) and a three-year note for $262,000, due November 1919. The team had also issued $150,000 of preferred stock held by Charles Taylor, the owner prior to Lannin; Frazee’s new ownership group was now responsible for both the dividend and the eventual principal repayment of this nonvoting equity interest. Frazee’s personal ownership interest in the franchise was 70 percent.5

Additionally, Frazee assumed a mortgage of $188,000 as part of the Fenway Park acquisition. (This was technically an indenture of trust, which is identical to a mortgage in terms of the loan security.) Frazee technically owned the stadium through an entity called Fenway Realty Trust, and the team leased the stadium from this company — a fairly typical arrangement between two sister companies. The stock of the Fenway Realty Trust (i.e., Frazee’s ownership interest in Fenway Park) was pledged as security for the $262,000 note.6 Taylor and a couple of associates held the mortgage on Fenway Park; on the sale from Lannin to Frazee, Lannin also apparently joined the mortgagees.7

The precise nature of Frazee’s capital sources are, of course, impossible to reconstruct at this late date, but it is fairly clear that he also borrowed his share of the $400,000 in cash necessary to purchase the team. In an unsigned loan-consolidation document dated May 1921, Frazee considered refinancing $343,250 of debts (exclusive of a new mortgage loan on Fenway Park, to be discussed later), of which $250,000 was owed to the Federal Trust Company and secured by 700 shares in the Red Sox franchise (the remainder was owed to various individuals and banks on behalf of his theater interests) — undoubtedly the major source of Frazee’s portion of the funds used to purchase the club. As further evidence of his large borrowings, Frazee and the Red Sox had large interest obligations: In 1920, the only year for which we have a complete team financial statement, the club paid $34,061 in interest (again, exclusive of the interest on the mortgage, which was a separate line item on the team financial statement — apparently the interest on the $250,000 was run through the club’s books), and, according to his tax return, he personally paid another $12,475 in interest that year. Looked at another way, if we assume an average interest rate of 6 percent,8 Frazee and the Red Sox needed to support payments of more than $50,000 based on roughly $850,000 of principal ($250,000 loan secured by the team + $262,000 note to Lannin + $150,000 preferred stock + $188,000 mortgage, and this does not include any potential borrowing by Ward).

The purchase by Frazee from Lannin was the first sale of an American League franchise not vetted and approved by American League president Ban Johnson. For many years Johnson had ruled the American League with dictatorial authority, earned through the successes at the birth of the league and long-term bonds forged with the league’s early owners. Newcomer Frazee felt little allegiance to Johnson and showed none of the deference Johnson had come to expect, and the two strong personalities disliked each other from the start. At the time bookies and organized gamblers operated relatively openly in many ballparks, and it was reputedly most blatant in Boston.9 Johnson seized on this gambling problem in Fenway Park in 1917 as a pretext to condemn Frazee.

Johnson and Frazee appeared to reach some sort of détente during the 1917–18 offseason. Frazee hired Johnson’s friend Ed Barrow as Boston’s manager, and Johnson likely facilitated the sale of three Philadelphia stars to Frazee, who was still optimistic about his baseball business, for $60,000. But any reconciliation quickly unraveled in the struggles of the confused, war-shortened 1918 season. Frazee was outspoken in his criticism of Johnson’s handling of the war complications and controversies. When the season ended, Johnson began campaigning to oust Frazee from ownership of the Red Sox, while Frazee lobbied to curb Johnson’s authority, going so far as to approach former U.S. president William Howard Taft about becoming a “one-man National Baseball Commission” that would oversee all of baseball.

The Carl Mays incident in 1919 finally cemented the divide of the American League into two warring factions. Mays, one of the league’s top pitchers, jumped the Red Sox in July, and, as the other league owners began offering packages of players and money to acquire him, Frazee looked to cash in. Johnson argued that an insubordinate player should not be able to force a trade and demanded the Red Sox suspend Mays. Frazee and the Yankee owners, Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston ignored, Johnson’s edict: The Yankees bought Mays for $40,000 and two players. Johnson then ordered Mays suspended and decreed he could not play for New York. The Yankees owners defied Johnson and obtained a court injunction permitting Mays to play for them. With this act of defiance, the Yankees owners became, at least as much as Frazee, the focus of Johnson’s enmity. Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, also feuding with Johnson, joined Frazee and the Yankees owners in a triumvirate committed to the dismissal, or at least neutering, of Johnson.

FINANCIAL STRUGGLES BEGIN

At the time Frazee purchased the Red Sox, they were one of the most valuable franchises in baseball. When Frazee offered to sell a piece of the team to Ed Barrow after the 1917 season and make him a club executive, Barrow attempted to raise the funds by borrowing from his wealthier baseball friends. In his solicitation letter Barrow called the franchise one of baseball’s most profitable, behind only the New York Giants and Chicago White Sox.10

Unfortunately for Frazee, profits from the club declined sharply after 1916 as attendance collapsed. The total gate decreased from 496,397 in 1916 to 387,856 in 1917 and then, in the war-shortened 1918 season, to 249,513. In 1919, Red Sox home attendance rebounded to 417,291, but the increase was smaller than what most other American League teams enjoyed. During these years the team’s revenue could not have been sufficient to service Frazee’s required interest payments. In 1920, for example, one of the most profitable years in baseball up to that time and the earliest one for which we could discover team financial statements, the Boston franchise turned a profit of only $5,970 after paying interest and the 6 percent dividend on the preferred stock.11

Although moderately successful with his theater ventures, Frazee was not earning anything close to enough capital to cover the costs of his baseball team, much less to accumulate substantial wealth. Frazee had two principal sources of theater-related income: the Cort Theatre in Chicago and producing his own plays. Frazee was president of the Cort Theatre Company and a 54 percent owner. As president he earned a salary of $12,000 per year, and as an owner he was entitled to his share of the profits.12

Unfortunately the profits were not particularly strong. The fiscal year ending July 31, 1916, resulted in a profit of $68,192, by far the theater’s best year. These substantial earnings may, in fact, have helped convince Frazee that he could afford to buy the Red Sox that November. But the Great War and its aftermath significantly cut into the operation’s earnings. For the fiscal years ending July 31, 1918, and July 31, 1919, the theater turned profits of only $4,544 and $5,225 respectively.13

The specific economics of Frazee’s plays are almost impossible to reconstruct at this point, nearly a century later, but it is clear from his tax returns and snippets of financial information related to his plays that he was not generating significant wealth prior to his hit No, No, Nanette in the mid 1920s (at least relative to the ownership of a baseball team and his other obligations). In an article on the economics of producing theatrical plays, Tino Balio and Robert G. McLaughlin highlight the difficulty of making money in this business: “One of the ironic and yet accepted truths of Broadway economics: productions, both large and small, can have substantially long runs and still show a loss when they close.” The authors examined a number of plays over the period 1938 to 1960 to underscore how difficult it was to turn a profit. 14

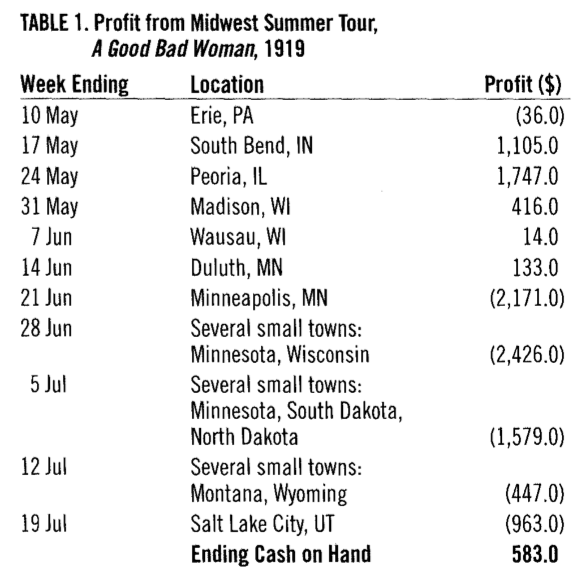

Table 1

(Click image to enlarge)

Although his career fell outside this time frame, Frazee clearly suffered from similar economics. On Frazee’s 1920 income tax return, for example, he shows a net loss of $42,534 for his theatrical companies. He claims a loss of $33,000 for My Lady Friends (B and C companies), $13,305 for Ladies’ Day, $5,989 for the Toy Girl, and $2,335 for Song Bird. He turned a profit on only one company, $12,096 on My Lady Friends (A company). Table 1 spotlights the profits (or lack thereof) for touring A Good Bad Woman through the Midwest in 1919.15 This picture mirrored an overall downward trend in road productions. In New York the theater rebounded for two seasons after the war but then hit another downturn when the country fell into a brief recession.16

Furthermore, Frazee often needed to sell off a significant ownership percentage to finance his productions, leaving him only a small percentage of the profits. According to the Internet Broadway Database (www.ibdb.com), Frazee’s longest-running show in the late 1910s was Nothing But the Truth, which ran from September 1916 through July 1917. (Notably, after this run Frazee had no play in production — presumably because of the Great War — until October 1918, a long time to be without theater revenue when his baseball team was struggling at the gate). Frazee, however, needed to sell off a majority interest in Nothing But the Truth, and it is unlikely he received a substantial premium.

In a letter dated June 13, 1917,17 Lawrence Weber, a sometime backer of Frazee, chastised him for his distribution of the profits: “You certainly seem to be laboring under a misapprehension as to your ownership of a considerable larger interest than you have.” Weber complained that, when they had repurchased Sam Friedman’s 10 percent interest for $3,500 (using Weber’s money), the “agreement was that this money was to be repaid to me out of the net balance of interest or 8% before any profits were declared,” later adding that “it is just five years since you made your first touch from me and it is about time that matters are cleaned up.” Hardly the tone or dollar amounts to be used with someone flush with cash.

Specifically, Weber pointed out that Frazee owned only 38 percent of the play and that, when he further sold out to Gilbert M. Anderson, Frazee was reduced to only a 3 percent interest. The letter noted that through June 9, 1917, the show made $42,778, a decent return but clearly not the kind of profit needed to generate the resources necessary to meet Frazee’s looming obligations.

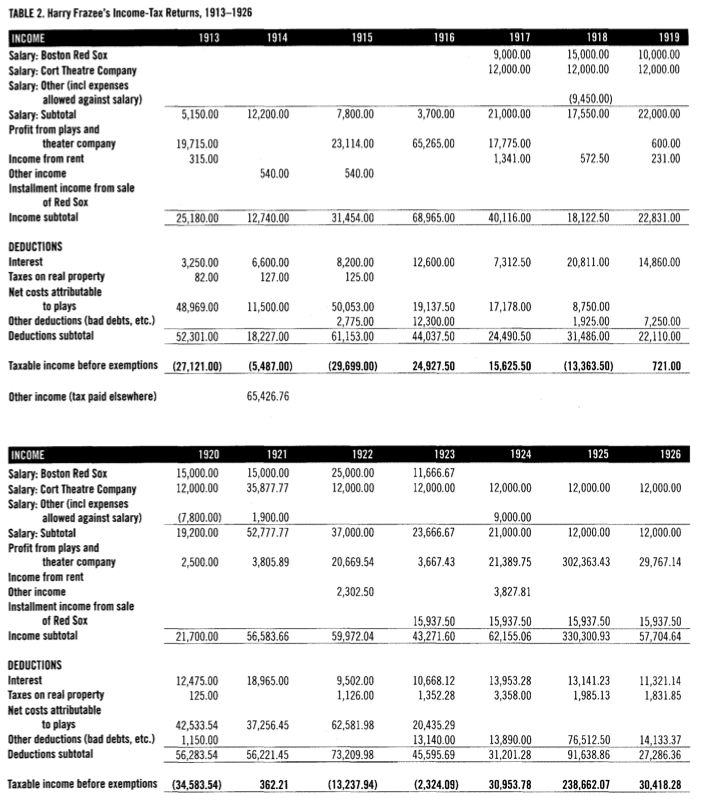

While the analysis of the incomplete baseball and theater documents available in the Frazee Papers may allow a little room for interpretation, his tax returns do not. We have summarized Frazee’s individual income-tax returns on table 2. His financial affairs were not particularly well organized, and he may have been exaggerating the deductible expenses associated with his plays. But even acknowledging that Frazee’s tax returns may have understated his actual cash available does not change the basic fact that he was earning well short of the amounts necessary to continue to service his considerable debts for the team and park. The loose papers and revenue- and-expense schedules attached to his returns further testify to the modest income (by baseball-franchise standards) Frazee was generating. As a further confirmation of the validity of the tax returns, several years after he died a final appraisal of his estate was released. He left $1,152,390 in gross assets and $713,925 in debts and other deductions, resulting in a net estate of $437,465 ($94,952 going to his widow, $189,125 to his son, and $153,378 being owed to his first wife).18 These amounts seem reasonable when compared with the last few years of available tax returns.

TABLE 2

(Click image to enlarge)

Our examination of Frazee’s tax returns revealed that in the late 1910s his earnings were falling well short of his commitments. After showing a negative taxable income of $26,699 in 1915, he earned $24,928 in 1916, his best year up to that point. This solid income and an expectation of more good years was almost certainly a key factor in his acquisition of the Red Sox that November. The next few years, however, were not kind to Frazee financially. In 1917 his income dropped to $15,626; in 1918 it actually dipped into the red with a negative net income of $13,364; in 1919 his income rebounded all the way to $721. Again, Frazee may have been overstating his expenses; he certainly lived beyond the means indicated by his taxable income. But his income would have had to have been a full order of magnitude larger to have met his looming financial obligations. Note, too, that when Frazee had his biggest hit several years later with No No Nannette, his tax returns did in fact reflect a much higher income.

Frazee’s continued personal borrowing from the Red Sox, often in relatively small amounts, further testifies to his relatively straitened economic circumstances. He often had the club pay some of his non-baseball-related expenses. Additionally, in 1919 he overdrew his salary by $5,850; in 1920 he overdrew his salary by $21,659 and pocketed another $5,000 on a note. At the end of 1920, according to the team’s financial statements, Frazee owed the club $38,293.

Soon Frazee not only found himself squeezed by the interest on all his debt, but in November 1919 the $262,000 principal on Lannin’s note came due as well. Magnifying the problem, Ban Johnson would gladly use Frazee’s financial distress to lever him out of baseball. Furthermore, Frazee was looking to purchase the Harris Theatre on West 42nd Street in New York, which would cost $410,000 later, in 1920. Although Frazee and his partner John Heyer eventually arranged for a mortgage of $310,000 on the theater, the partners still needed to contribute $100,000 in equity. Frazee clearly needed fresh funds — and quickly — to support his two businesses.19

THE SALE OF RUTH

With his financial squeeze mounting, on January 5, 1920, Frazee announced the notorious sale of Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees. For Ruth, Frazee received the record sum of $100,000: $25,000 up front and three promissory notes of $25,000 each at a 6 percent interest rate, due in November 1920, 1921, and 1922. In addition Ruppert gave Frazee a three-month commitment that he would lend him $300,000 to be secured by a first mortgage on Fenway Park.20 With Ruth dispatched, the Red Sox would not finish in the first division again until 1934.

All parties to the transaction consistently maintained that Frazee needed money. Ed Barrow, the Red Sox manager at the time, later recalled that Frazee set up a meeting in the café of the Hotel Knickerbocker in New York to tell Barrow about the deal. “Lannin is after me to make good on my notes,” Frazee told Barrow. “And my shows aren’t going so good. Ruppert and Huston will give me $100,000 for Ruth and they’ve also agreed to loan me $350,000 [sic]. I can’t afford to turn that down. But don’t worry. I’ll get you some ballplayers, too.” Barrow further added that Frazee “showed me how much he owed, how much he had lost at Fenway Park, and how urgent it was that he get the $500,000 which would be made available by the sale of Ruth.” 21

Yankee owners Ruppert and Huston each stated that Frazee sold Ruth because he needed the funds. Both, particularly Huston, were close friends of Frazee and were well acquainted with his financial situation. They recognized that Frazee was being squeezed and needed to pay off Lannin’s note. Ruppert also later remarked on Frazee’s relatively small initial cash investment relative to the price of the franchise: “Joe Lannin, from whom Frazee had bought the Boston club on a shoestring, was hollering for his money.”22 In a separate account, Huston told the same story: “Frazee found it necessary to do some financing in his baseball ownership,” he recalled. “There was a mortgage of about $300,000 on the Boston club and grounds and the holders of this paper called it — insisted on having the money.” 23 This certainly referred to the $262,000 note due Lannin, the security for which was actually Frazee’s equity interest in Fenway Park.

Fred Lieb, a longtime baseball writer and author of several baseball books in the 1940s and 1950s, is another primary source for these details. “Harry Frazee,” he wrote, “once told the author the rape wasn’t premeditated. He didn’t plan it that way; it just happened. He needed money, and the Yankee colonels, Ruppert and Huston, hungry for a winner, had plenty of it.” (Lieb credited sportswriter Burt Whitman with coining the phrase “the rape of the Red Sox” to describe the sale of Ruth and other players, mostly to the Yankees.” Lieb continued: “‘The Ruth deal was the only way I could retain the Red Sox,’ Frazee once told the author in a moment of confidence.”24

FINANCIAL STRUGGLES WORSEN

Unfortunately, the sale of Ruth did not immediately clear up Frazee’s financial obligations. For one thing, Frazee’s finances were relatively disorganized, and his attorneys were having difficulty cleaning up the existing mortgage so that the new one from Ruppert could be secured. In the meantime, Frazee immediately began trying to borrow against his three $25,000 notes from the Ruth sale. On December 30, 1919, Colonel Huston wrote to his partner Jacob Ruppert: “I told Mr. Frazee that I would try to get him a short term loan at my bank, with one of the notes we gave the Boston Club as collateral.” In February 1920, Huston again sent a message to Ruppert on financing the notes: “Mr. Harry Frazee is asking us to aid in getting three $25,000 notes discounted. He says events with Mr. Lannin have made it impossible to follow his original intention of having the notes discounted in Boston.” Frazee wanted cash immediately by either selling or borrowing against the three $25,000 notes.25

In a friendly but supplicating letter to Frazee on January 11, 1920, Joseph Lannin expressed dismay at the delay in Frazee’s repayment of his $262,000 note after Lannin had extended the date and stipulated, “as agreed by you, that payment would be made before December 4.” Lannin added that he needed the money for several of his own obligations:

“I have purchased some property and have been granted two extensions, but the owners refuse to give me a further extension of time, so I must get this money or meet with considerable financial loss, as I would forfeit a substantial payment that I have already made. I have also agreed to take an interest in the Mercedes Automobile Agency, depending on receiving this money from you.”26

In February 1920, as Frazee’s attorneys struggled through the outstanding mortgage issues with Taylor’s group, Lannin sued to have his security (Frazee’s ownership interest in Fenway Park) auctioned off, with the proceeds going to pay off his note. To delay and mitigate repayment of his debt to Lannin, Frazee claimed that, when he had acquired the club, he had unexpectedly taken on an additional obligation of $60,000 to $70,000 that was rightfully owed by Lannin as part of a legal settlement baseball owners made with the Federal League.27

On March 8, Frazee’s and Lannin’s attorneys signed a stipulation resolving the dispute wholly in favor of Lannin. The settlement called for Frazee to pay $25,000 by March 8, another $25,000 by March 22, and the $215,000 balance by May 3, and Lannin would earn interest on all funds not paid by April 5. (Why this settlement included an extra $3,000 to Lannin is not clear, but several items were in play, and the extra payment could have been for interest, legal fees, or some other associated cost.) To access Ruppert’s loan, however, the cash-strapped Frazee still had to clear up the existing mortgage on Fenway Park (including refinancing Taylor’s preferred stock). Otherwise, the ballpark could not be used as collateral for the $300,000 loan from Ruppert. In April 1920, as his attorneys finalized arrangements for the release of the existing mortgage, Frazee sent to Ruppert a letter asking for the loan, to which Ruppert agreed:

You remember that I phoned you about ten days before the expiration of your agreement to make a loan of $300,000 on Fenway Park and asked you to extend the time, which you advised me you would tell Mr. Grant to do. However, I have received no word from Mr. Grant. I telephoned Col. Huston today, as I could not reach you on the phone, asking the Colonel to see you and advise that I have cleaned up all matters upon the Preferred Stock which your Attorney wanted before making the loan and I am now ready to accept it on May 15.

You can understand how important this is to me as my plans have all been based on my ability to secure this loan. Therefore, will you please send me signed agreement, copy of which Mr. Grant has, stating that you will advance the $300,000 . . . and if possible make the date May 20th. . . . I need this agreement signed by you here very badly to complete the balance of my negotiations. [Our emphasis28

The mortgage would have netted Frazee about $175,000 in new funds ($300,000 less the balance on the existing mortgage of roughly $125,000).29 And so, in total, the Ruth transaction freed up about $275,000 for Frazee to meet his financial obligations. Eventually Frazee purchased his theater and settled with Lannin, sending him the final payment of $216,003 (including some additional interest) on May 3.30

As evidence for the claim that Frazee had no financial worries, Stout has suggested a couple of other reasons for the Ruth sale. As it is now obvious that Frazee desperately needed money to pay off Lannin and purchase his theater, these alternative reasons are basically irrelevant. They also do not hold up to careful scrutiny. Stout makes much of the fact that Boston writers and fans did not universally pan the sale of baseball’s biggest star to their biggest rival. Of course one of the main reasons for the wait-and-see attitude was Frazee’s announcement in the wake of the sale: “With this money the Boston club can now go into the market and buy other players and have a stronger and better team in all respects than we would have had if Ruth had remained with us.”31 Many writers believed Frazee’s story, though eventually they would learn differently.

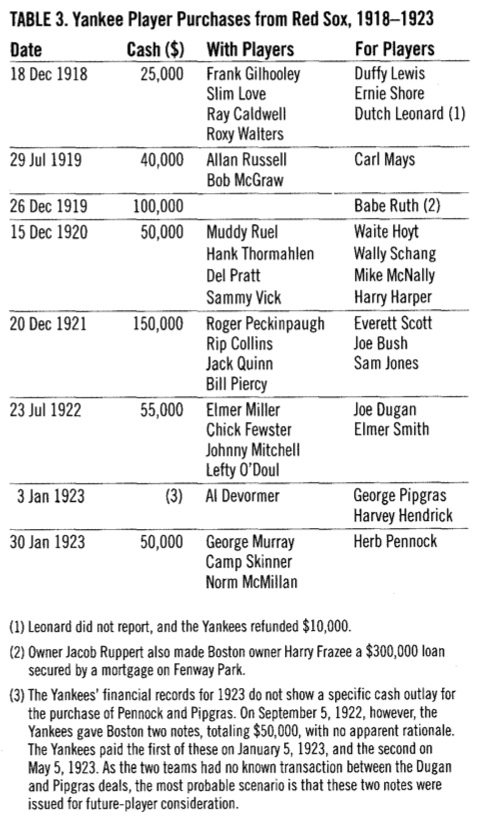

Table 3

(Click image to enlarge)

Moreover, by the end of the 1919 season, Ruth’s status as the game’s best player and biggest celebrity at the tender age of 24 belied Frazee’s later claim that Ruth was actually a detriment to the club. In 1919 he set the single-season home-run record with 29, when no one else hit more than 10. He also hit .322, led the league in RBIs, and went 9–5 in 133.3 innings pitched for good measure. He may have been hard to manage, but the Red Sox had already won three world championships with Ruth, and on the Yankees he would go on to win another seven pennants and four World Series, while the New York club typically led the league in attendance. Ruth was a player who created a winner both on the field and at the box office. Frazee, a clever theatrical promoter, naturally recognized Ruth’s value — so much so that he leveraged him into $100,000 and a $300,000 loan. Ruth’s purchase price was by far the highest in baseball history at the time, higher than the prices paid for Tris Speaker and Eddie Collins just a few years earlier, surely a sign of just how valuable he was perceived to be.

The re-mortgage of Fenway Park only prolonged Frazee’s need for a steady influx of cash, and over the next few years he became addicted to financial injections from the Yankees owners. As confirmed in the Yankees financial records and shown in table 3, subsequent to the Ruth sale Frazee sold the rest of his top players to the Yankees for more than $300,000. When the Yankees won their first World Series in 1923, four of the eight starting position players and four-fifths of their starting rotation had come from the Red Sox. The Red Sox finished last in the American League, and their skeletal remains would be the doormat of the league for many years.

Somewhat quixotically, Stout and Johnson claim that Frazee made sound baseball deals with the Yankees and that he could not have foreseen what the trades would do for either club. This argument makes no sense either. Ed Barrow, manager of the Red Sox from 1918 through 1920, left the Red Sox and became general manager of the Yankees. Barrow knew the Red Sox players as well as anyone, and he spent the next few years grabbing all of the good players, like future Hall of Fame pitchers Waite Hoyt and Herb Pennock, catcher Wally Schang, shortstop Everett Scott, third baseman Joe Dugan, and pitchers Joe Bush and Sam Jones, among others. In fact Barrow liked his former players enough that he got the Yankee owners to give Frazee $305,000, convincing evidence that both teams agreed that the talent was imbalanced. To argue that Frazee made good deals is to suggest that Barrow and the Yankees somehow lucked into their dynasty and that the money was not the central piece of the deal for Frazee.

In July 1923, Frazee sold the team for $1,150,000 — $850,000 for the team plus the assumption of Ruppert’s $300,000 mortgage — to a group led by baseball man Bob Quinn and money partner Palmer Winslow.32 Under the terms in the draft contract available in the Harry Frazee Papers, Quinn’s group paid $350,000 down ($150,000 went to pay off Frazee’s refinanced note to Taylor for his preferred stock) and then $500,000 over the next eight years.

During the 1920s, Frazee continued to produce plays, and in 1924 he launched his biggest hit, No, No, Nanette. It opened in Detroit and achieved hit status several weeks later when it reopened at the Harris Theater in Chicago. A year later Frazee opened the musical on Broadway to popular acclaim, in line with the top productions of the era. It ran for 321 shows, “considerably fewer than the 477 for Wildflower, the Youmans hit that preceded it, or 352 for Hit the Deck, which followed it. But the short run could be easily excused: Audiences in New York were already so familiar with the show from its Chicago and road success that they did not have to see it on Broadway to enjoy it.”33 As his tax records indicate, Frazee netted more than $300,000 on No, No, Nanette in 1925, by far his most profitable year ever.

After No, No, Nanette, Frazee opened only one more Broadway production, Yes, Yes, Yvette, which flopped and was cancelled after forty performances.34 Frazee died on June 4, 1929, from Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment. Frazee, a Mason, had no religious service; Masonic rites were performed by Judge Peter Schmuck as chaplain. New York mayor Jimmy Walker delivered the eulogy.35

FRAZEE AND THE PRESS

By the time of Frazee’s death, the reasons for his dismantling of the Red Sox (to raise cash) had become the accepted wisdom. In his syndicated column just before Frazee died, Westbrook Pegler of the Chicago Tribune compared the destruction of the Red Sox to the case of the Giants’ Phil Douglas offering to throw a game in exchange for money. “The drunken pitcher would have done the same things to the Giants that Mr. Harry Frazee did to the Red Sox, only to a much smaller degree,” Pegler wrote.36 On Frazee’s death in June, the Associated Press story claimed that, after the World Series triumph of 1918, Frazee “began meeting his obligations by converting star Boston players into cash.”37

By the middle of the 1920s, as the magnitude of the Yankees dynasty and the depth of the Red Sox ineptitude became clear, sportswriters began to vilify Frazee’s destruction of the Red Sox. Of particular interest to this story are the views of Shirley Povich, a prominent Jewish sportswriter (identified by religion for reasons that will become clear from what follows) for the Washington Post for seven decades. On Bill Carrigan’s return to manage the Red Sox in 1926, Povich wrote that Carrigan would never have worked for Frazee, who “dispos[ed] of his good ball players to the highest bidder.”38 A year later, in a story about his hometown Senators, Povich wrote that “cash does not have the same magnetic property . . . it boasted a few years ago, when Harry Frazee was selling Boston Red Sox in wholesale consignments to the Yankees.”39 In a story about Tom Yawkey’s purchase of the team in 1933, Povich sounded the same theme: “Frazee proceeded immediately to wreck the team.”40

More telling still is an Associated Press story that ran when Ruth was acquired by the Boston Braves in 1935. “And Boston fans,” wrote the AP, “who still shudder when the name of the late Harry Frazee is mentioned, will never forget how he ruined a championship club to make the Yankees a winner.”41

When Lieb’s book was published in early 1947, it received a generally favorable review from Harold Kaese, one of the more respected Boston writers at the time. In recounting the section on Frazee, he wrote that a “mass transferal of manpower led to the long period of Yankee supremacy, while wrecking the Red Sox until Tom Yawkey bought them in 1933.” Kaese says of the book that “little that has not been hitherto revealed is brought to light.” Including, of course, Lieb’s even-handed and decidedly accurate account of Harry Frazee’s gutting of the Red Sox for cash.

Having written all of this, we can easily see how an indictment of Frazee could go too far. What Frazee did to the Red Sox — sell off the assets of a championship club without reinvesting in other players — has been done many times in baseball history, including twice by the much revered Connie Mack. Frazee was a man struggling to pay his bills, and he was able to sell all of his good players and then sell the club at a profit. There is a certain charm in his brazenness.

Has there been a tendency on the part of some Red Sox fans to blame Harry Frazee for their entire 85-year-championship drought, fans who believed that Frazee’s dealing of Ruth placed a curse on the club? We seriously doubt the validity of this point of view, popular though it is, but, to the extent that Frazee was blamed for the state of the franchise beyond the mid-1930s, that is obviously unfair. The club was economically competitive once Tom Yawkey bought the team, and other scapegoats will have to be found for the years between 1933 and 2003. But for Frazee’s tenure at the helm, the historical record is clear. The Boston Red Sox won the World Series in 1918, and over the next five years Harry Frazee sold Babe Ruth and other players to the Yankees for upward of $450,000. The shell of a baseball team he sold in 1923 was the doormat of the league until Tom Yawkey reinvigorated the franchise a decade later.

The “Jew”

On what evidence have Glenn Stout and others come to reject the conventional wisdom and revise the historical record, effectively exonerating Frazee from the wrecking of his team? Stout attributes Frazee’s problems with Ban Johnson and his later negative portrayal in the press to anti-Semitism. According to Stout, Johnson [Ban, not Stout’s coauthor Richard Johnson] and Fred Lieb were anti-Semitic. Therefore Johnson’s actions and Lieb’s writing should be disregarded as the work of bigots. Relative to Stout’s charge, two items are clear. First, regardless of the motivation of Frazee’s detractors, the historical record is unmistakable: Frazee sold Ruth and others because he needed the money for his theatrical ventures and baseball debts, not as a way to improve his ballclub. Second, his charge of anti-Semitism is baseless.

Although Frazee was a Mason and his activities of a religious nature were generally focused on Freemasonry, he came from a well-established line of Presbyterians, which the family traced back to colonial times.42 Stout postulates that both the general public and close associates believed Frazee was Jewish because of a couple of relatively flimsy details: Frazee, born in Peoria, Illinois, was a New York theatrical producer, employed in an occupation with a disproportionate number of Jews; and an article in the Dearborn Independent, a virulently anti-Semitic weekly published by Henry Ford, referred to him as a Jew in an article headlined “How Jews Degraded Baseball” (September 10, 1921).

The reference in the Independent is the solitary piece of evidence we are aware of suggesting Frazee was Jewish, and it needs to be viewed with a healthy dose of skepticism. Regarding its accuracy, on occasion Ford referred to people as Jews if he disliked them and they exhibited what he considered Jewish characteristics, even if they were not actually Jewish.43 It is certainly possible that readers — even sympathetic ones — would not have taken all of Ford’s accusations literally. (Ford did not write the articles; he conveyed his themes and thoughts to writer William Cameron, who then articulated them in print.)

Furthermore, by late 1921 the impact of the Independent within mainstream society was waning. As historian Neil Baldwin points out, the Independent’s circulation in late 1920 was about 300,000, but by early 1921 it had fallen to less than half that. Ford initially urged his car dealers to purchase the weekly and pressed them to sell subscriptions to their customers. Many bought them on their own or for their friends and families simply to placate Ford. As these burned off and were not renewed, circulation fell.44 To put the circulation in context, in 1920 there were at least ten magazines with a circulation of more than 1,000,000.45 A review of Ayer’s annual directory of circulation indicates that in 1920 roughly 85 magazines had a circulation of at least 300,000.46 Obviously a magazine with such a divisive theme and well-known publisher could attract attention disproportionate to its circulation, but it was clearly a small voice among many competing interests.

Perhaps even more significantly, in response to the Independent’s maliciousness, a statement titled “The Perils of Racial Prejudice” and undersigned by more than one hundred well-known Americans, including two presidents and president-elect Warren Harding, was published in many newspapers around the country on January 16, 1921. Baldwin, quoting a historian of anti-Semitism, argues that, several weeks after this piece appeared, “it was clear that Henry Ford stood alone in the United States.”47 And so, by the time the article calling Frazee a Jew appeared in September, the Independent had been marginalized, even if it remained a terrifying channel for anti-Semitism. The point here is not to minimize the danger from even peripheral voices of hate but to highlight how many people generally in the mainstream may not have seen the reference to Frazee as a Jew or may not have believed it if they did.

The Frazee Papers include many items one might expect, such as personal tax records, receipts on his theater productions, and business correspondence. They also include a wide range of other material — tax-record notes scribbled on scraps of paper or the backs of envelopes, press clippings about his son being jailed for speeding, unredeemed baseball tickets, a letter from a young man requesting employment. In all of this material, other than a copy of the offending Dearborn Independent, we could find no references to, or implications of, Frazee’s supposed Judaism.

In fact, there are only two “religious” references in all of his collected papers. These are two undated Christmas cards, which the Frazees sent out. One says “Yo Ho and a Merry Christmas. Mr. and Mrs. Harry Herbert Frazee.” The other, underneath a picture of a dog pulling the leash held by a couple of children, reads: “The Frazee jrs. Ann, Harry, Harry III, Robert & ‘the Duke’ himself, are pulling for a Merry Xmas and a Happy New Year to all.”

Frazee’s papers also depict his close relationship with aviator Charles Lindbergh. Frazee organized the banquet for Lindbergh in New York City after Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight in 1927, and Lindbergh stayed at Frazee’s home after the flight. Although there is some debate about Lindbergh’s level of anti-Semitism, it is unquestioned that he was an unrepentant eugenicist, that he made anti-Semitic speeches before the United States’ entry into World War II, and that he had a close relationship with Henry Ford. After his transatlantic flight, Lindbergh could have stayed at any home in America. Would he really have chosen to stay at the home of someone perceived to be a Jew?

In sum, we find it highly unlikely that the Peoria-born Frazee, who sent out Christmas cards and was descended from a long line of Presbyterians, would be mistaken as Jewish. Moreover, the two individuals Stout most specifically charged with anti-Semitism in their treatment of Frazee — Johnson and Lieb — both knew Frazee well and would have known whether he was Jewish. And even if they did believe he was, can we really determine that their deeds and words were dictated by anti-Semitism? What evidence is there that the two men hated Jews at all?

The single item of circumstantial evidence for Johnson’s anti-Semitism is that, in contrast to the National League, the American League, after the inaugural 1901 season ((majority Baltimore stockholder Sidney Frank was Jewish) had no Jewish owner until after he left the presidency in 1927. This is a flimsy piece of evidence on which to tar a man. Moreover, that a Jewish owner still did not come into the American League until after 1946 partially exonerates Johnson from being singled out as uniquely anti-Semitic.48 A strain of anti-Semitism in the form of negative Jewish stereotypes and quotas limiting Jews in colleges and occupations was common in the early twentieth century. This may have been in play among baseball executives, but it seems unreasonable to single out Johnson.

Stout and Johnson also theorize that Frazee sold Ruth to bolster his alliance with the Yankees owners against Johnson. This argument makes no sense. Most obviously, there is no cause and effect between the sale and the bolstering of the alliance unless one claims that Ruth was sold at a large discount in exchange for some sort of nebulous agreement from the Yankees owners to support Frazee against Johnson. One cannot exonerate the sale of Ruth as a valuable baseball player and simultaneously claim he was worth more than $100,000. More importantly, the Yankees owners were even more at the forefront of the imbroglio with Johnson than was Frazee; they would have needed Frazee’s support against Johnson more than vice versa. Any transaction between the Yankees owners and Frazee was a consequence of their social relationship and alliance against Johnson, not a cause. Johnson’s feud with the Yankees owners and Comiskey was just as bitter as with Frazee; there is no reason to attribute anti-Semitism to this quarrel.

Stout wrote that anti-Semitism against Frazee gained traction from the Dearborn Independent article, that Frazee received balanced press before the article and generally bad press after it.49 But the Independent article ran in September 1921; Johnson’s feud with Frazee was most bitter in the years 1917 to 1920. By the end of the 1921 season both Frazee, with his lousy team, and Johnson, now second fiddle to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, were largely irrelevant. Furthermore, if the baseball press was more critical of Frazee after the fall of 1921, it is certainly understandable. The Red Sox finished in last place in eight of the nine years following the publication of the Dearborn Independent article, while the Yankees won pennants with stars purchased in Frazee’s fire sale. One would expect his press coverage to change as the reality of the pillaging of his team began to take hold. In 1920 there were members of the press who bought his line about reinvesting in the Red Sox the money he got from the Ruth sale. Once it became clear that he would not, and would also pocket $300,000 more from the Yankees, his defenders understandably had dwindled.

Stout saves worse opprobrium for longtime Lieb. According to Stout, the anti-Frazee sentiment died down for twenty years after Frazee’s departure from the baseball scene, only to be reintroduced by Lieb in his 1947 history of the Red Sox. (As noted in the main body of this article, this is false. There were numerous references to Frazee’s destruction of the team before the publication of Lieb’s book. Within baseball circles, it was an accepted truth.) “Yet underneath his button-down exterior,” Stout writes, “Lieb was rife with prejudice.”50

Unfortunately, Stout’s evidence for Lieb’s anti-Semitism is embarrassingly thin, amounting to Lieb holding “the easy anti-Semitism so rampant within American society during the era between the wars.”51 Lieb was a giant in his profession for more than xity years, and any prejudices he may have held (and we know of none) did not extend to his writing.

In an article in The Sporting News (September 12, 1935), Lieb directly addresses the issue of Jews in baseball. This lengthy piece, published piece years before Lieb’s supposed anti-Semitic book on the Red Sox, focused on Hank Greenberg as the greatest Jewish baseball player, but Lieb also included the top Jewish players at each position; what Lieb described as “a first class all-Jewish team could now be picked from major leaguers past and present.”52

Lieb began the article by trying to answer the question “Why isn’t there a real outstanding Jewish ballplayer?” He answers that “it was my theory that the race had been held back in developing along baseball lines by lack of opportunity.” Lieb continues:“It was my contention the Jew did not possess the background of sport that was the heritage of the Irish. . . . Therefore he became an individualist in sport, a skillful boxer and ring strategist, but he did not have the background to stand out in a sport which is so essentially a team game as baseball.”

This could be read unsympathetically, but Lieb follows up in the next paragraph with the argument that “this theory may once have had something to it, but in the past few years, it has been knocked into a cocked hat by the big bat of Hefty Hank Greenberg of Detroit and the Bronx.” The rest of the article raves about Hank Greenberg and his excellent chance to be the American League’s Most Valuable Player, points out how the New York teams let Greenberg slip away, and discusses the positive performances of other Jewish major leaguers. Throughout the article, Lieb’s tone is supportive and appreciative.

Stout also imputes anti-Semitism to Lieb because of his belief in the occult. While Lieb was an occultist, we have been unable to find an association that would make him anti-Semitic. In Sight Unseen, one of his two books on the occult, Lieb claimed that Mark Anthony — in Lieb’s story Antony spelled his name with an h — communicated with him and his wife through their Ouija board. Lieb described Anthony’s thoughts on current events (the book was published in 1939): “He is anti-Mussolini . . . he is more friendly to Hitler. Once he said Hitler’s treatment of the Jews was partly justified. Inasmuch as I am of German decent, psychologists might attribute this favorable attitude toward Hitler to personal leanings in my subconscious mind, but neither my wife nor I are admirers of the Fuhrer; being religious and political liberals and friends of humanity we strongly condemn his intolerance, his gag on free speech and his medieval anti-Semitic crusade.”53 Even if one concludes that Lieb possessed the easy anti-Semitism of the era, his attitude was, by definition, unexceptional. And more significantly, it did not flow thorough to his writing about Jews.

Lieb later tells the story of Jewish umpire Albert Stark favorably and sympathetically. Lieb admired Stark’s single-minded determination to reach the major leagues, a virtue that eventually paid off when he became one of baseball’s top umpires in the 1930s. Lieb is sensitive to Stark’s disillusionment on finally reaching his goal and uses Stark as a sympathetic figure of what happens when one directs his single-mindedness towards earthly goals.54

Lieb also wrote a popular history of the Pittsburgh Pirates. He writes admirably about Jewish owner Barney Dreyfuss: “When the former Paducah bookkeeper closed his earthly books, his contribution to baseball was large. He was one of the game’s greatest and most far-seeing club owners.”55 Yet we are to believe that Lieb decided to destroy Frazee’s reputation (it was already ruined) because he was Jewish (he wasn’t)? This simply does not agree with the record of Lieb’s long and distinguished writing career, in which he repeatedly wrote favorably of other Jewish baseball people.

In an outrageous tarring, Stout attempts to tie Lieb to Henry Ford through Lieb’s acquaintances. Stout writes that “Lieb was almost certainly aware of the Independent. He was well read and the first editor of the Independent was journalist E. G. Pipp, uncle of Yankee first baseman Wally Pipp, who Lieb regularly covered on the Yankee beat. Detroit sportswriter H. G. Salsinger, a close friend of Lieb, occasionally contributed innocuous baseball features to the Independent.”56

As if that is not enough of a stretch, E. G. Pipp was not anti-Semitic, and he strongly objected to the anti-Semitic content of the paper. In April 1920, he resigned in disgust as editor of the Independent, this before the publication of the first anti-Semitic article, on May 22, 1920. E. G. Pipp went on to found a newspaper to counter Ford’s anti-Semitism.57 Additionally, that a baseball-writing colleague “occasionally contributed innocuous baseball features to the Independent” is absurd evidence that Lieb shared Ford’s anti-Semitism. Stout himself writes that Salsinger’s articles were “occasional” and “innocuous.” Undoubtedly, given the easy anti-Semitism of the era, Lieb had friends who held negative stereotypes of Jews. To jump from this to claim that Lieb’s accurate portrayal of Frazee was driven by anti-Semitism is fantastic.

Ironically, Stout’s complete lack of documentary evidence (supporting the charge of anti-Semitism directed against Frazee) is precisely the criticism Stout levels at Fred Lieb. Contrary to Stout’s assertion that Frazee died with his reputation intact and that it remained so until Lieb smeared him in 1947, Lieb did nothing to change the generally held opinion of Frazee. The story of Harry Frazee recounted by Fred Lieb in his book, an account no different from the commonly accepted view, is well told and fundamentally true.

Notes

1 Fred Lieb, The Boston Red Sox (New York: Putnam, 1947).

2 Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

3 The most extensive treatment of his Frazee thesis is “A ‘Curse’ Born of Hate,“ by Glenn Stout, ESPN.com, 3 October 2004, http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/playoffs2004/news/story?page=Curse041005.

4 Frazee papers, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; hereinafter, Frazee Papers.

5 Boston Globe, 11 February 1920. Two documents from the early 1920s refer to Frazee‘s 70 percent interest: a draft refinancing agreement from May 1921 that was apparently never consummated, and a Frazee financial statement for year ended 31 October 1922. It is certainly possible that Frazee‘s interest had changed slightly since he first acquired an interest in the team several years earlier, but this would not affect the basic outline of his finances.

6 Boston Globe, 11 February 1920.

7 The Frazee papers contain a letter dated 12 January 1920, from attorney T. J. Barry to Frazee, conveying an alternative mortgage-loan proposal from a potential lender other than Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert. In the proposal reference is made to the fact that the “present de facto Trustees are Messrs. Taylor, Lannin and Lannin. The records at the registry of deeds do not show that . . . the election of Messrs. Lannin and Lannin were accomplished in accordance with the requirements of the declaration of trust.“

8 The dividend rate on the preferred stock and the interest rate on the loan proposal in note 7 above were both 6 percent, as was the rate on the notes taken back by Frazee in the Ruth sale.

9 Daniel E. Ginsberg, The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1995), 84–85.

10 Letter from New York Yankees documents auctioned by Sotheby‘s, 24 June 2006.

11 Frazee Papers.

12 Frazee Papers.

13 Frazee Papers.

14 Tino Balio and Robert G. McLaughlin, “The Economic Dilemma of the Broadway Theatre: A Cost Study,” Educational Theatre Journal 21, no. 1 (March 1969): 82.

15 Frazee Papers.

16 Jack Poggi, Theater in America: The Impact of Economic Forces, 1870–1967 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press), 29–33, 51–52.

17 The letter does not specifically state the name of the play, but the relatively large dollar amounts and that “Nothing But the Truth“ was the only Frazee show running anywhere near 1917 make it almost certain that Weber was referring to “Nothing But the Truth.“

18 New York Times, 23 August 1933.

19 Freyer Realty Company tax returns for 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924, Frazee Papers.

20 Stout mistakenly believes that this mortgage was not part of the Ruth sale; see, for example Glenn Stout in When Boston Still Had the Babe: The 1918 Champion Red Sox, edited by Bill Nowlin (Boston: Rounder Books, 2008), 166. This is certainly incorrect; the mortgage loan of $300,000 was an integral component of the Ruth transaction. In addition to the document quoted below, Ruppert wrote: “We paid $100,000 for Ruth. And I personally made a loan of $370,000 [sic] to Frazee, taking a mortgage on Fenway Park as security“ (New York World-Telegram, 19 February 1938). Moreover, Lannin expected a mortgage loan to be part of Frazee‘s capital raising. In a letter (11 January 1920) to Frazee, pleading for his money, he wrote: “I was mightily pleased to learn from you yesterday that you had arranged your finances so that permanent loans may be placed on the Park and that it is now only of retiring the bonds [the existing mortgage that took Frazee another couple of months to clear up]. Even more convincingly, on 12 January 1920, Ruppert‘s attorneys sent to Frazee a letter stating that they had received the invoices and asking for payment to the real-estate appraisers who “supplied us with the valuations of Fenway Park, which were necessary to be submitted to Col. Ruppert before he could make a decision as to whether to agree to make a loan against mortgage.“

21 Edward Grant Barrow, with James M. Kahn, My Fifty Years in Baseball (New York: Coward-McCann, 1951), 108.

22 Colonel Jacob Ruppert, as told to Dan Daniel, “Behind the Scenes of the Yankees,“ New York World-Telegram, 19 February 1938.

23 Bozeman Bulger, “The Baseball Business from the Inside,“ Collier‘s, 25 March 1922.

24 Lieb, The Boston Red Sox, 178, 182–83.

25 Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 208.

26 Frazee Papers.

27 Boston Globe, 11 February 1920.

28 Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life, 209.

29 Boston Globe, 11 February 1920.

30 Boston Red Sox, 1920 financial statements, Frazee Papers.

31 Boston Globe, 6 January 1920.

32 James Quirk and Rodney W. Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press), 401; draft purchase and sale agreement, Frazee Papers.

33 Don Dunn, The Making of No, No, Nanette (Citadel Press, 1972), 38.

34 Internet Broadway Database, www.ibdb.com.

35 New York Times, 5 June 1929.

36 Westbrook Pegler, in Chicago Daily Tribune, 8 May 1929, p. 29.

37 Associated Press, in Hartford Courant, 5 June 1929, p. 1.

38 Shirley Povich, in Washington Post, 14 December 1926, p. 17.

39 Shirley Povich, in Washington Post, 2 December 1927, p. 15.

40 Shirley Povich, in Washington Post, 27 February 1933, p. 29.

41 Associated Press, in Hartford Courant, 27 February 1935, p. 11.

42 Frances Frazee Hamilton, Ancestral Lines of the Doniphan, Frazee and Hamilton Families (W. M. Mitchell Printing, 1928).

43 Neil Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate (New York: Public Affairs, 2001), 106, 243–44.

44 Ibid., 146.

45 Carl F. Kaestle et al., Literacy in the United States: Readers and Reading Since 1880 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991), 263.

46 N. W. Ayer and Son‘s American Newspaper Annual and Directory, 1920.

47 Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews, 150–51.

48 Michael T. Lynch Jr., Harry Frazee, Ban Johnson, and the Feud that Nearly Destroyed the American League (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2008), 162.

49 Glenn Stout, “A ‘Curse’ Born of Hate,” http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/playoffs2004/news/story?page=Curse041005.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Paper of Record.

53 Frederick G. Lieb, Sight Unseen: A Journalist Visits the Occult (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1939), 112.

54 Ibid., 227–29.

55 Frederick G. Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (1948; Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 47.

56 Glenn Stout, “A ‘Curse’ Born of Hate,” http://sports.espn.go.com.

57 Stock Maven, at http://www.stockmaven.com/logsdon99_F.htm; http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/anti-masonry/dearborn.html; Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews, 98–100.