Dartmouth Street Grounds (Boston)

This article was written by Charlie Bevis

The Dartmouth Street Grounds in Boston hosted major-league baseball in 1884 when the Boston team in the Union Association played its home games at this ballpark. During its five-year life (1884 to 1888), the ballpark was used to host not only baseball games but also a variety of other sporting activities. In the fall of 1888, the state of Massachusetts acquired a portion of the land to build a state militia armory on the site.

The Dartmouth Street Grounds in Boston hosted major-league baseball in 1884 when the Boston team in the Union Association played its home games at this ballpark. During its five-year life (1884 to 1888), the ballpark was used to host not only baseball games but also a variety of other sporting activities. In the fall of 1888, the state of Massachusetts acquired a portion of the land to build a state militia armory on the site.

Because Boston did not enter the Union Association until mid-March 1884, there were only six weeks to establish a business organization, locate suitable land for a ballpark, and erect a grandstand to conduct the first home game, scheduled for April 30. The ballclub was owned by investors in the Union Athletic Exhibition Company, which was formed on March 26, 1884.1 Frank Winslow, the proprietor of Winslow’s Roller Skating Rink, was the president.2 One of the primary investors was George Wright, who was reportedly instrumental in Boston’s entry into the Union Association, after securing the contract for his sporting-goods company, Wright & Ditson, to provide the official baseball of the league.3

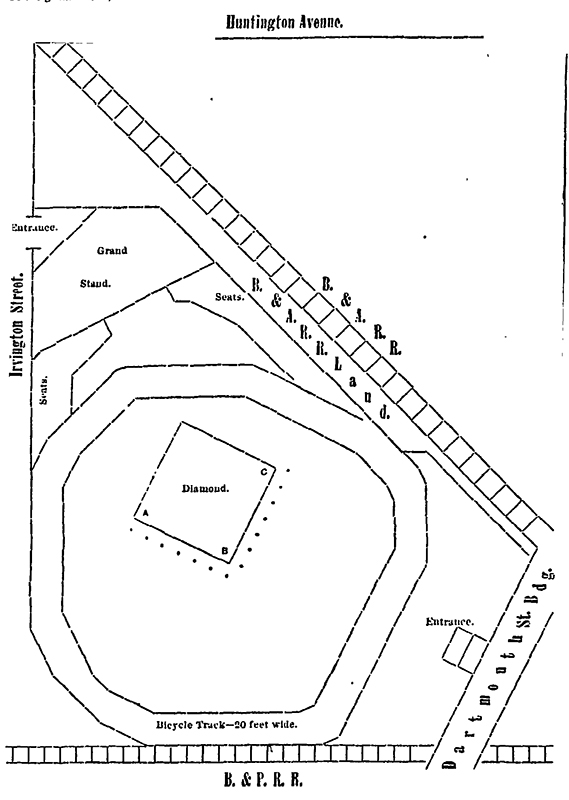

For a ballpark, the Union Athletic Exhibition Company leased a triangular piece of land covering 134,000 square feet in the Back Bay section of Boston, bounded by the Boston & Albany Railroad (north), Dartmouth Street (east), Boston & Providence Railroad (south), and Irvington Street (west).4 The term of the lease was three years, with an option for renewal.5 The rent was likely inexpensive given the relative lack of demand for this awkwardly situated piece of land between two railroad tracks.

This land was owned by the trustees of the Huntington Avenue Lands, a trio of wealthy businessmen headed by banker Franklin Haven. When purchased from the Boston Water Power Company in 1871, this land was under water, part of the polluted marshland known as the receiving basin that resulted from the damming of the Charles River.6 The Huntington Avenue Lands were “made land,” created by a landfill that converted the tidal flats into usable land.

By 1875 soil had filled the section of the Huntington Avenue Lands between the two railroad tracks (the area of the leased land for the ballpark).7 By 1883 little of the Huntington Avenue Lands near the railroad tracks had been sold, given its limited commercial value.8 Before the lease with the Union Athletic Exhibition Company, this land was largely unused, except for a few weeks each summer when a traveling circus came to Boston. The circuses promoted this land as the “coliseum grounds,” in reference to the large temporary building erected for the Peace Jubilee and Musical Festival in 1869 on the nearby landfill along Dartmouth Street east of the railroad tracks.9

Samuel Thayer was the architect of the Dartmouth Street Grounds, which had a total seating capacity of about 4,575.10 The wooden grandstand had a roof and chair seats for 1,523 spectators; six private boxes atop the grandstand, with walls of corrugated iron and roofs of incombustible material, had preferred seating for another 50 people; and the uncovered bleachers along the first- and third-base sides could seat 3,000.11 Underneath the grandstand were restrooms, a refreshment stand, and dressing rooms for the ballplayers.12 The stands were built by the construction company Clark & Lee.13

The ballpark was designed to be a multipurpose facility, with a cinder track for bicycle races and a large field to stage other activities in addition to baseball. The dimensions of the baseball field have been estimated to be 419 feet to left field, 325 feet to center field, and 274 feet to right field.14 The bicycle track was 20 feet wide and went around the perimeter of the baseball field, close to fence in right and center fields, through the middle of left field, then through foul ground between the infield and the seating areas.

The facility was initially referred to as the Dartmouth Street Grounds, to leverage the cachet of the upper-class Back Bay neighborhood and nearby Copley Square, where the Museum of Fine Arts was then located. A secondary consideration was the proximity to the horse-drawn streetcar line of the Metropolitan Railway that passed by the entrance to the grounds on Dartmouth Street.15

The Dartmouth Street streetcar line connected to the main line on Boylston Street to provide the most convenient access for patrons traveling from the central business district to the ballpark.16 This entrance was also convenient to the streetcar line of the Highland Railway on Columbus Avenue, on the other side of the Boston & Providence Railroad, where patrons could cross the tracks on the Dartmouth Street bridge to get to the ballpark.17 People were familiar with the Dartmouth Street entrance, not just because of the streetcar line but also because that had been the only entrance to the see the circus when these traveling troupes came to town prior to 1884.

There was a second entrance to the ballpark on Irvington Street, which the city of Boston had created in April 1884.18 Irvington Street stretched from Huntington Avenue to St. Botolph Street, about halfway to the ballpark boundary with the Boston & Providence Railroad. This was the upper-class entrance to the ballpark, since it led directly to the grandstand and the private boxes.19 These patrons needed to walk just a short distance from the streetcar line on Huntington Avenue or from a nearby parking area if they came by private carriage.

Harry McGlenen was hired to be manager of the Union Athletic Exhibition Company (not to be confused with the manager of the baseball team, Tim Murnane). His job was primarily to book other events to supplement the scheduled games of the Boston Unions, but also to handle advertising of the baseball games.20 For the initial baseball games at the ballpark, McGlenen advertised its name as the “Boston Union Athletic Co.’s Grounds,” with the location at Huntington Avenue and Dartmouth Street.

One of the first tenants was the semipro Commercial Base-Ball Players League, with teams sponsored by individual employers and single trades, which used the ballpark for some league games.21 The rent was probably free so that the Union Athletic Exhibition Company could collect some admission fees on days that the venue would have otherwise remained empty. Bicycle races were popular attractions in 1884, as were running competitions and football games.

The most serious problem faced by the Union Athletic Exhibition Company was the competition at the South End Grounds, where the Boston team in the National League played its games. Even with admission at 25 cents, half the price at the South End Grounds, the Union Athletic Exhibition Company had difficulty drawing spectators to see the games of the Boston Unions.22 Total attendance for the 1884 season was a mere 28,000 admissions, roughly one-fifth of the attendance at the South End Grounds.

On April 30, 1884, the first major-league baseball game was played at the Dartmouth Street Grounds, when the reported attendance was 2,800 people.23 There was no competing National League game that day, though. At the next Unions game on May 2, only 300 people attended, compared with 1,800 for the game at the South End Grounds. On May 3, the Unions game was “sparsely attended,” as 3,000 went to the National League game that day.24 The Boston Unions played just four games at home before heading back on the road again.

For the Decoration Day holiday on May 30, there were two Commercial League baseball games played in the morning and bicycle races in the afternoon. Attendance for the bicycle races was reported to be 2,000 people.25 Bicycle races proved to be more popular events at the ballpark than baseball in 1884.

During the second week of the three-week homestand in June, the Boston Unions had to compete not only with the National League games but also with the Barnum & London circus that set up on the vacant land adjacent to the ballpark. Competition from the circus seemed to be serious enough that advertisements for the games of the Boston Unions soon reflected the location of the ballgames as the “old coliseum grounds,” trying to draft off the popularity of the nearby circus grounds.26 In July the ballgames were advertised as being at the “Boston Union Coliseum Grounds.”27

During the summer months in 1884, the Union Athletic Exhibition Company experimented with nighttime events conducted under artificial lighting. On July 3 athletic contests were held at the ballpark, which included several running and bicycle races.28 On July 30 a wrestling match was staged under the lights before an audience of 1,300 people.29 In the fall there were lots of bicycle races in September, with football games dominating the October and November calendar, such as the October 25 game between Harvard College and the Institute of Technology.30

The preferred reference to the ballpark soon became the Union Grounds, based not on the baseball team but on the name of its lessee, Union Athletic Exhibition Company. The ballpark was never associated with the prestigious Back Bay, since it was a stone’s throw from the less affluent South End on the other side of the Boston & Providence Railroad tracks.

The Union Association folded after the 1884 season. Without professional baseball during 1885, the ballpark was used mostly by college and semipro baseball teams that summer. When the minor-league New England League added a Boston team for the 1886 season, the ballclub used the ballpark to play its home games.31 The team was known as the Boston Blues, based on their dark blue home uniforms, to distinguish it in the newspaper from the National League team.

The Blues played four preseason games in April and four regular-season games in early May at the ballpark before they were evicted in early May. Before the season, Winslow of the Union Athletic Exhibition Company “made a verbal agreement with the directors [of the Blues] to let them have the grounds for half the net profits,” but was unhappy with the early results so he demanded “half of the net receipts” instead. When the Blues refused to agree to the new financial arrangement, Winslow locked the gates at the ballpark to prevent the Blues from playing their scheduled game on May 10.32 The Blues then arranged to play their home games at the South End Grounds.

For the 1887 baseball season, the Boston Resolutes, a team of black players, planned to play their home games at the ballpark during the first season of the National Colored Baseball League. The Resolutes did play one preseason game there, on April 12, but never got the opportunity to host a regular-season game, as the ballclub disbanded after its first league game, played on the road in Louisville.33

Following the demise of the Resolutes, the ballpark was used mostly for amateur baseball games in the spring and summer and college football games in the fall. The last professional baseball game at the ballpark was played on October 18, 1887, when Detroit met St. Louis in a neutral-site game that was part of the barnstorming 1887 World Series.

In January 1888 the Union Athletic Exhibition Company set up a toboggan slide at the ballpark, where people could slide down a chute from the top of the grandstand and travel over the ice-covered ball field to the outfield wall near the Dartmouth Street entrance. The grounds were open day and night (when lit by Japanese lanterns) for toboggan rentals. For the summer months in 1888 the grounds were leased to the YMCA, which used it for a variety of activities, including lawn-tennis courts.34

In the fall of 1888 the state of Massachusetts acquired the portion of the ballpark that bordered the Boston & Providence Railroad tracks and Dartmouth Street in order to erect a state militia armory on the site.35 The city of Boston extended Irvington Street from its previous terminus at St. Botolph Street to the railroad tracks to provide access to the new building, which was known as the South Armory.36

Since the residual land of the old ballpark had minimal commercial value, due to its diminished size and lack of entrance on Dartmouth Street, the Boston Athletic Association (BAA) leased the remaining land to use as an outdoor running track. From 1890 to 1898 the BAA conducted track meets at the site on a 220-yard cinder track known as the Irvington Oval.37 “The place, though small, has proven to be a source of great profit, athletically, to the Club, and its value cannot be overstated,” the BAA track coach wrote about the Oval in a summary of the track team’s 1890 accomplishments.38

In 1897 the Irvington Oval was the site of the finish line for the 24.5-mile BAA Road Race, which soon became known as the Boston Marathon. John McDermott won that inaugural race, which was held simultaneously with a track and field competition at the Oval. “McDermott ran the one lap on the oval required to finish the course like a half-miler,” the Boston Globe reported, “and looked and acted as though he were capable of doing even better.”39 In the 2012 book commemorating the 125th anniversary of the BAA, author John Hanc wrote: “A crowd of 3,000 packed the nearby Oval, where the plucky New Yorker covered the final lap of the race in forty seconds, paced by two dozen spectators who ran alongside him.”40 The Irvington Oval was again the site of the finish line for the 1898 marathon, before the BAA moved the finish line in 1899 to be on Exeter Street in front of the BAA clubhouse.

By 1901 the Irvington Oval was used less often for track meets, since the northern portion of the land under old ball grounds was sold to build a seven-story dormitory, called Technology Chambers, for students at the nearby Institute of Technology.41 While the BAA reoriented the outdoor track to fit into the remaining small lot between the dormitory and the armory, the slimmed-down Irvington Oval was now more suitable for football practice than track meets. In 1909 the BAA constructed a board track with banked corners to replace the flat, cinder track.42 However, in 1915 this last open portion of land under the old ballpark was sold to build an automobile garage.43

The last sporting events to take place on land of the former Dartmouth Street Grounds were indoor track meets in the armory building, which was used for high-school competitions for nearly a half-century following the demise of the Irvington Oval. In May 1962 the land under the armory was taken for the construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike and the armory was demolished.44 A turnpike interchange was built on this land in 1964. Today, the Copley Place shopping mall, built in 1983, sits atop the turnpike interchange on the land once occupied by the Dartmouth Street Grounds.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen. Photo illustration from Boston Globe, April 3, 1884.

Notes

1 “Organization of the Union Athletic Exhibition Company,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1884.

2 “Boomed Roller Skating: Frank H. Winslow Is Dead,” Boston Globe, June 12, 1905.

3 Jerry Jaye Wright, “What’s in a Name? George Wright’s Influence, Favors and Deals During the Organization of the Boston Unions of 1884,” North American Society for Sport History, 1990.

4 “The Union Grounds: Plans for the New Athletic Park Completed,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1884; G.W. Bromley, Atlas of the City of Boston, 1888, City Proper, plate 44.

5 “Organization of the Union Athletic Exhibition Company.”

6 Nancy Seasholes, Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 197.

7 Seasholes, Gaining Ground, 198.

8 G.W. Bromley, Atlas of the City of Boston, 1883, Boston Proper, plate P.

9 P.S. Gilmore, History of the National Peace Festival and Great Musical Festival (Boston: self-published, 1871), 385.

10 “The Union Grounds: Plans for the New Athletic Park Completed.”

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 “Real Estate,” Boston Globe, April 27, 1884.

14 Correspondence with Ron Selter, an authority on nineteenth-century ballpark dimensions, November 15, 2017.

15 Advertisement in Boston Globe, April 27, 1884.

16 “The Union Grounds: Plans for the New Athletic Park Completed.”

17 Advertisement in Boston Globe, April 27, 1884.

18 A Record of the Streets, Alleys, Places, Etc. in the City of Boston (Boston: City of Boston, 1910), 258.

19 “The Union Grounds: Plans for the New Athletic Park Completed.”

20 “Base Ball Briefs,” Boston Globe, April 5, 1884.

21 “Commercial Base-Ball Players,” Boston Daily Advertiser, March 25, 1884.

22 Advertisement in Boston Globe, April 27, 1884.

23 “The New Grounds Opened,” Boston Globe, May 1, 1884.

24 “Boston Unions 12, Keystones 11,” Boston Globe, May 4, 1884.

25 “The Ramblers’ Races: Two Thousand People Present at the Union Grounds,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1884.

26 Advertisement in Boston Globe, June 22, 1884.

27 Advertisement in Boston Globe, July 13, 1884.

28 “Athletics by Electric Lights,” Boston Globe, July 4, 1884.

29 “Downed by Dufur,” Boston Globe, July 31, 1884.

30 The Institute of Technology, a college located in the Back Bay near the Dartmouth Street Grounds, was better known two decades later as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) after it relocated to Cambridge.

31 “Players for Boston’s N.E. League Nine,” Boston Globe, March 7, 1886.

32 “Soden to the Rescue: Frank Winslow Closes the Union Grounds,” Boston Globe, May 11, 1886.

33 “Plans of the Colored Club,” Boston Globe, January 23, 1887; “The Resolutes Open the Season on the Union Grounds,” Boston Globe, April 13, 1887.

34 “Union Grounds Leased to the Young Men’s Christian Association,” Boston Globe, April 21, 1888; “New Union Grounds Opened,” Boston Post, June 4, 1888.

35 “Armory at South End,” Boston Globe, October 6, 1888; “The Proposed Regimental Armory at the South End,” Boston Globe, November 18, 1888.

36 G.W. Bromley, Atlas of the City of Boston, 1890, City Proper and Roxbury, plate 14; A Record of the Streets, 258.

37 “B.A.A. Juniors,” Boston Globe, May 28, 1890; “Besides Marathon Race,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1898.

38 John Hanc, The B.A.A. at 125: The Official History of the Boston Athletic Association, 1887-2012 (New York: Sports Publishing, 2012), 38.

39 “Record Time: J.J. McDermott Wins the ‘Marathon’ Race,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1897.

40 Hanc, The B.A.A. at 125, 53.

41 “Will Be a Magnificent Structure,” Boston Globe, June 23, 1901; “Handsome Home for Tech Students,” Boston Globe, December 8, 1902; G.W. Bromley, Atlas of the City of Boston, 1908, Boston Proper and Back Bay, plate 23.

42 “To Be Open to All Runners,” Boston Globe, December 1, 1908.

43 “Irvington St. Oval Gone,” Boston Globe, November 24, 1915.

44 “State Awarded $950,000 for So. Armory Seizure,” Boston Globe, December 19, 1963.