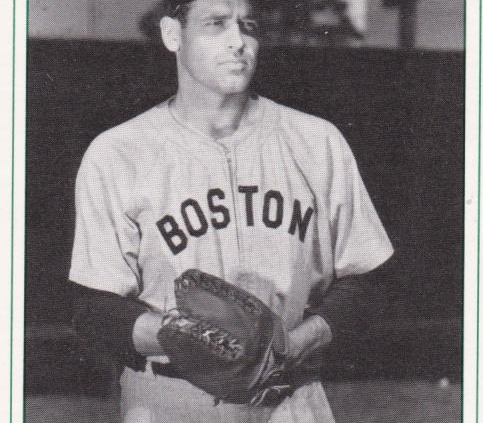

Jake Jones

Jake Jones made one of the loudest debuts in the history of the Boston Red Sox. After Joe Cronin swapped slumping first baseman Rudy York — who had knocked in 119 runs for the AL champs in 1946 — to the visiting Chicago White Sox for Murrell Jones on June 14, 1947, York’s first response reportedly was, “I’ve been traded for who?” Streaming into Fenway Park for a doubleheader the next afternoon, bewildered Red Sox patrons were referring to their new player as “Muriel.” After the games the same fans were calling Cronin a genius, for Jones drove in seven runs and homered in both games of the Red Sox sweep. With the nightcap knotted at 4-4 in the ninth, Jones arrived to the plate with the bases full and two down. Ted Williams and Bobby Doerr had drawn intentional passes in the inning so Jake was on the spot. His former mates in the visiting dugout were letting him have it, hollering that he couldn’t deliver in the clutch, but they couldn’t have been more wrong. Producing under fire was Jones’s forte and he sent the first pitch into the left-field screen for a walk-off grand slam.

Jake Jones made one of the loudest debuts in the history of the Boston Red Sox. After Joe Cronin swapped slumping first baseman Rudy York — who had knocked in 119 runs for the AL champs in 1946 — to the visiting Chicago White Sox for Murrell Jones on June 14, 1947, York’s first response reportedly was, “I’ve been traded for who?” Streaming into Fenway Park for a doubleheader the next afternoon, bewildered Red Sox patrons were referring to their new player as “Muriel.” After the games the same fans were calling Cronin a genius, for Jones drove in seven runs and homered in both games of the Red Sox sweep. With the nightcap knotted at 4-4 in the ninth, Jones arrived to the plate with the bases full and two down. Ted Williams and Bobby Doerr had drawn intentional passes in the inning so Jake was on the spot. His former mates in the visiting dugout were letting him have it, hollering that he couldn’t deliver in the clutch, but they couldn’t have been more wrong. Producing under fire was Jones’s forte and he sent the first pitch into the left-field screen for a walk-off grand slam.

Jake almost did not receive full credit for his game-winning blast. “Bobby Doerr, who was on first base when Jones hit the ball over the fence,” reported the Boston Globe, “ran down to second base, touched the bag — and then headed to the clubhouse.

“Just as Doerr reached the vicinity of the pitcher’s box, he saw Coach Del Baker waving at him and suddenly realized that — although the winning run was scored — a rookie’s home run was at stake.

“He then turned back and resumed his trip around the bases.

“If Doerr had not turned back, it would have changed the score of the game to 5-4 — instead of 8-4.”

Jones was surrounded by reporters after the game. Tex Hughson told them he had played a hunch, stating, “He’ll hit a home run on the first pitch” to his teammates as Jake walked toward the plate. Johnny Pesky looked at Jones and said, “He’s strong. I’m glad he is on our side.” When someone said that Jones had a pretty good day, Eddie Pellagrini exclaimed, “Pretty good day! That’s a pretty good week.”

Impressive as Jake’s day had been though, it was far from his best effort. That had come several years earlier when he flew a Hellcat off the USS Yorktown in the Pacific. Jones’s final tally in aerial combat was seven planes shot down, and the highly decorated ace had rung up one of the most impressive war records among all ballplayers in the military.

James Murrell Jones was born in rural Epps, Louisiana, on November 23, 1920. His parents were Luther A. Jones Sr. and Della Virginia Moore Jones. His childhood was spent in Epps and nearby Monroe, Louisiana. Family and friends called him “JM” or Murrell, the nickname “Jake” being hung on him either in the minor leagues1 or the military,2 depending on the source. His Boston teammates simply called him “Jonesy.” Following his graduation from high school in 1938 he began his baseball career in Louisiana with the semipro Clarks Lumbermen. In 1939, he hit .321 with 14 home runs and 103 RBIs for Monroe in the (Class C) Cotton States League, and in 1940 he put up .301 / 16 / 75 numbers for Shreveport in the (Class A1) Texas League.

Jones was on the fast track to the majors. In addition to his powerful bat, he displayed an innate ability to scoop up low throws around first base. “Jones reached his defensive peak in the Texas League all-star game at Beaumont,” wrote the Shreveport Journal on August 14, 1941, “when he practically saved the hides of the southern division team with sensational fielding feats on bad throws. He was so nearly the whole show that he was acclaimed the most valuable player in the game and will receive a trophy designating him as such.”

A number of big league teams were bird-dogging Jones: the Pirates, Yankees, Giants, and White Sox were reported as the interested parties, and his 20 round-trippers by early August — he led the Texas League with 24 for the season — had not escaped the notice of at least one Hall of Famer, for “Detroit’s immortal Harry Heilmann has labeled Jones as one of the greatest natural hitting prospects he has ever seen.”3 With rumors about that “he might draw $75,000 from the pocketbook of a big league magnate,”4 Jones was sold to the Chicago White Sox for $25,000 on August 23, 1941.5

His major league debut came a month later, on September 20, and he went hitless in his first six games, totaling 21 at-bats over parts of two seasons, until breaking through with two safeties against Washington’s Early Wynn on April 30, 1942.

Sent back down to the minors for additional seasoning, Jones enlisted in the Navy during the summer of 1942. Despite never having gone to college, he was selected for flight training — the assumption being that, like Ted Williams, his quick reflexes made him superbly qualified for the task, and on August 1, 1943, Jones was commissioned an ensign. Jake told his son that he played basketball at the University of North Carolina while in the service and information received from the military’s National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis lists his place of entry into the service as Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

The USS Yorktown (CV-10) — nicknamed “the Fighting Lady” — was the second aircraft carrier of that name to serve in World War II, the original (CV-5) being lost at the Battle of Midway. Jones joined the ship in time for her second deployment to the Pacific.

For two weeks in November 1944, the Yorktown launched air strikes on targets in the Philippines in support of the invasion of Leyte. It was during this action that Jones was awarded his first Air Medal. His citation, signed by Vice Admiral J. S. McCain, the grandfather of Arizona Senator John S. McCain III, read as follows:

“For distinguishing himself by meritorious acts while participating in an aerial flight as pilot of a carrier based fighter airplane assigned to strike against enemy installations and shipping in the vicinity of the Philippine Islands on 14 November 1944. He performed his assignment as wingman for the Air Group Commander in an outstanding manner and destroyed an enemy fighter during our attack. His skill and courage were at all times inspiring and in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Promoted to lieutenant junior grade, Jones quickly picked up a second Air Medal.

“For meritorious achievement in aerial flight as pilot of a fighter plane in Fighting Squadron THREE, attached to the USS Yorktown, in action against enemy Japanese forces in the vicinity of the Philippine Islands, December 14, 1944. Participating in a strike against the enemy, Lieutenant Junior Grade, Jones pressed home a daring attack against three enemy fighters, destroying one, inflicting severe damage on another and forcing the third to flee. His skill, courage and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

The November 2001 issue of Naval History magazine printed an article written by Rear Admiral MacPherson B. Williams, U.S. Navy (Retired), who had been the Yorktown’s Air Group Commander.6 The article was entitled “I Was Alone in Enemy Territory” and it was about his harrowing experience in evading capture after being shot down.

“It was 16 December 1944. The U.S. Navy Task Force was 150 miles east of the Philippines. As the air group commander in the USS Yorktown, ‘The Fighting Lady,’ I was leading the morning strike. We launched and rendezvoused over the pocket destroyer on the starboard bow and headed west toward our objective, climbing for altitude and testing our guns on the way. We were at 15,000 feet when we topped the cloud cover of the eastern shore of Luzon and saw the wide expanse of the Manila Plain below.

“Over Nichols Field, our target, we peeled off, delivered our bombs, and ducked low to Manila Bay to get under their flak. We then turned south beyond Sangley Point and the ruins of Cavite Navy Yard to join up over Laguna del Bey…

“With 40 minutes to spare, I released the three section leaders to browse on their own and join me, over Laguna del Bey, in 30 minutes.

“My wing man, Jake Jones, and I went up the Pasig River to Marikina Air field, where reconnaissance photos had shown there were hidden Japanese aircraft. The low level attack we delivered resulted in a small antiaircraft hit in my engine. Realizing trouble, we headed toward the hills on the eastern side of Manila Plain. The fire in my engine got bigger and finally into the cockpit with me. Having no choice, I bailed out….”

Williams suffered painful burns to his arm when he bailed out, but landed safely. He spent several weeks behind enemy lines before he was able to reach friendly forces.

As for Jones, 10 combat missions flown between January 3 and January 15, 1945, in the vicinity of Formosa, China, French Indo-China and Nansei Shoto earned him his third and fourth Air Medals. A week later, he won his first Distinguished Flying Cross. Highlights of that citation are as follows:

“For heroism and extraordinary achievement in aerial flight as pilot of a fighter plane in Fighting Squadron THREE, attached to the U.S.S. Yorktown, during action against enemy Japanese forces in Formosa on January 21, 1945. Participating in a long instrument flight, Lieutenant Junior Grade Jones carried out a low altitude attack in the face of intense antiaircraft fire, scoring rocket hits to set a large hostile oiler on fire and contribute to the success of the mission….”

On February 16 and 17, the Yorktown launched strikes on mainland Japan near Tokyo where Jake downed five enemy planes to win the Silver Star and another Distinguished Flying Cross. Years later he told his son that he flew back to the Yorktown from one of those missions with a hole in a wing that was big enough for a man to climb through. The citation highlights, the Silver Star first and then the second Distinguished Flying Cross, are as follows.

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy during the first carrier based strikes against the Japanese homeland on February 16, 1945. While flying a carrier based fighter plane he countered aggressive, determined and skillful attacks by numerically superior enemy fighters. He succeeded in shooting down three of these enemy fighter planes. After air opposition had been neutralized he, with his wingman, made low-level rocket and strafing attacks against air field installations, securing destructive hits on each of six hangers.…”

“For heroism while participating in aerial flight against the enemy during the first carrier based strikes against the Japanese Homeland on February 17, 1945. While flying a carrier based fighter plane as section leader in his Air Group Commander’s division, he countered the attacks of aggressive, determined and numerically superior enemy fighters. In this action he shot down two of these attacking planes. His skill and courage were at all times in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Jones returned home a hero. He received a week of shore leave in New York City, where he appeared on the Kate Smith radio show. Legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice, quoting an anonymous shipmate, wrote of Jones:

“A great guy and one of the best flyers I ever saw. Jake was on the FIGHTING LADY, one of the fightingest carriers in the war. And Jake was one of the fightingest pilots in the outfit — his record was seven Jap planes shot down in combat and, in addition to this, he was responsible for the sinking of at least four Jap ships. His war campaign included the Philippines, Formosa, China, Iwo Jima, Okinawa and missions over Tokyo. It was over Tokyo that three Jap flyers ganged up on him and he got all three.

“Jake got to play some baseball between flights, but not too much. I recall once when he came back from a flight and we had quite a party that night. It was on the island of Maui. Next day Jake played ball and got two home runs and a triple, to break up the game. He certainly could put the wood against that ball.”7

Commander George Earnshaw, a former pitching ace for Connie Mack’s great Philadelphia Athletics World Series squads of 1929-1931, was a shipmate on the Yorktown and several photos of the pair, probably used by the Navy for publicity purposes — think “two major leaguers at war” — are known to exist. It is likely that Earnshaw was Rice’s anonymous source.

Jake’s older brother, Major Luther A. Jones Jr., piloted a B-29 named the City of Monroe in over 20 combat missions in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Luther was awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Air Medals. The City of Monroe’s bombardier was Hollywood actor Tim Holt.8

Returning to baseball after the war, Jones was the only legitimate power threat on the White Sox team that finished last in the American League in 1946 with just 37 round-trippers. Veteran Hal Trosky opened the season as the starting first baseman but manager Jimmie Dykes soon moved Jones into the lineup and on May 3 his first major league home run proved to be the game winner versus the Philadelphia Athletics. His second home run, a two-run shot at Comiskey on May 15 which countered a Ted Williams round-tripper, was the big blow in a 3-2 victory over the Red Sox. His walk-off double on May 22 produced a 5-4 victory over Philadelphia.

Though Jones had returned unscathed from the Second World War, he did not have the same luck on the baseball diamond and on May 26, 1946, he suffered a season-ending fracture of his left wrist and elbow when Detroit shortstop Eddie Lake ran into his outstretched arm when trying to beat out an infield hit. Shortly after the season The Sporting News reported that Jones was having trouble straightening out his surgically repaired arm and was a carrying around a bucket of sand for several hours a day for physical therapy.9

Manager Ted Lyons started his 1947 spring training sessions at Pasadena, California, unsure of who his first baseman would be. In addition to Jones, he looked at veterans Trosky and Joe Kuhel before opening the season with Don Kolloway. Jake saw little playing time in April but in May he had six doubles and three home runs for the still punchless Chicago squad. Then his bat went silent. Streaky as they come, Jake was capable of carrying the team when he was hot, but extremely impotent with the bat when he was cold. At the time of the trade to the Red Sox, his batting average was .240.

In his first 11 games with the Red Sox, all played in Boston, Jones hit .302 with three doubles, three home runs, and a triple. His swing was tailor-made for Fenway Park, where in 1947 he hit .280 with 12 doubles, three triples, 14 home runs, and 57 RBIs in just 250 at-bats. In 325 at-bats away from Fenway that year, he hit .203 with nine doubles, one triple, five home runs, and 39 RBIs. He scored 39 runs in Boston and 26 elsewhere.10 Three players hit 10 or more home runs in Fenway Park in 1947. Ted Williams had 16, Jones 14, and Bobby Doerr 12. Jake hit one in Boston while with the White Sox, but after the Jones-York trade on June 14, the leading Fenway home run hitters were Jones with 13, Williams with 11, and Doerr with 10.11 “Too bad he can’t carry the left field fence with him on the road,” said the Boston Globe of Jones on September 10, 1947.

The line on Jake was that he didn’t show much emotion on the field and he chased low outside curves. His response to the first was simple: “When you have to fly through a lot of flak, you don’t scare easily on a baseball field.” Pitcher Dizzy Trout described Jones’s predilection for the slow curve: “He misses a couple of curves by a mile and you feel certain you’ve got him, and then he makes a monkey out of you by blasting the ball out of the park.”12

Soon the opposing teams started stacking the deck. “Jones is strictly a pull hitter and teams like the Chisox, Yankees, Indians, and Tigers shift their infields on him, bunching their men on the left side of second base, just the opposite of the way they play Ted Williams.”13

Jake was capable of delivering the big hit. While with Chicago in 1947 he had at least two game-winning at-bats; a fly ball that produced the deciding run in a 3-2 victory over Washington on May 18 and a 10th-inning single that accounted for a 9-8 victory over the Yankees on June 9. Jake’s base hit following Ted Williams’ triple delivered a 7-6 victory over Washington on July 5. His ninth-inning triple against Washington’s Early Wynn on August 12 resulted in a 2-1 Boston win. The next day Jake hit back-to-back homers with Bobby Doerr and added a second homer in a 10-3 victory over Washington. On September 1 he drove home all four Boston runs in a 4-1 win over the Yankees. His three-run homer on September 9 was the vital hit in a 5-3 victory over Detroit. Jake’s 19th and final round-tripper of the season, on September 17, accounted for the first two runs of Joe Dobson’s one-hit, 4-0 masterpiece over St. Louis.

On July 27 the Red Sox swept a doubleheader from the Browns at Fenway. In the sixth inning of the first game, Jake topped a foul ball that dribbled down the third base line. Though there was no chance that the ball would be fair — and as third baseman Bob Dillinger was about to pick it up — pitcher Fred Sanford threw his glove at the ball. Umpire Cal Hubbard, despite a vehement protest from the Browns, awarded Jones a triple on the 60-foot foul, basing his decision on the fact that the word “foul” was missing from the rule regarding prohibiting a fielder from throwing his glove at a batted ball. Baseball’s Rules Committee later amended the wording.

Jones was involved in another odd play, coming in the same August 12 game against Washington which was previously mentioned. With Washington batting in the fifth, and with Rick Ferrell on third and Early Wynn on second, Joe Grace hit a sharp grounder to Jake, who stepped on first to record the second out of the inning. Ferrell had held third on the play, but Wynn, not paying attention, took off for the same occupied bag. Seeing both runners standing on the same base, Jones sprinted across the diamond and tagged both runners. The umpire signaled that the final out of the inning had been recorded and Jones was credited with an unassisted double play, one out recorded at first base and the other at third.

Joe McCarthy replaced Joe Cronin as Red Sox skipper after the 1947 season. The former Yankees skipper did not share the same opinion of Jones’s ability as Cronin and in December, two months before spring training, announced that outfielder Stan Spence, newly acquired from the Senators, would be his first baseman in 1948.14 Oscar Fraley, a writer for the United Press who covered the Red Sox spring camp in Sarasota, wrote:

“So Jones sits it out in spring training even though he hit 19 homers last season compared to 16 for Spence and knocked in 96 runs compared to 73 for the former Senator.

“A left-field hitter, Jones is a dangerous batter in the Red Sox home park, and while he may not impress McCarthy, he received a tidy tribute from Cronin last winter when McCarthy was on his shopping spree.

“For about that time, Joe DiMaggio bumped into Cronin and, kiddingly, asked the Red Sox general manager when Cronin was going to purchase him from the Yankees.

“Cronin said the Red Sox might trade Jones for joltin’ Joe, which struck Demag — and a lot of others — something like swapping a Rembrandt for a comic book.

“But Cronin pointed out that DiMaggio only hit one more home run last season than Jones and only knocked in one more run, which is a fair measure of measuring a player’s value. Still Jones gets the deep freeze, without benefit of explanation, as Marse Joe oils the buttons labeled with stars.”

Shirley Povich of the Washington Post also interviewed McCarthy on his two big infield decisions, the other being the more remembered Pesky-Stephens issue:

“I was talking to one of McCarthy’s former Yankees the other day at St. Petersburg, and he had some comment on McCarthy’s big decision to shift Johnny Pesky from shortstop to third base, instead of Vernon Stephens. ‘We thought the Red Sox were going to be tough to beat,’ said the big Yankee, ‘but if McCarthy plays ‘em that way, we’ll lick ‘em.’

“So at Sarasota yesterday I asked McCarthy about that and he wasn’t perturbed at all. ‘I didn’t move Pesky because he couldn’t play shortstop,’ he said. ‘Why don’t my friends let me do the worrying? Pesky and Stephens are interchangeable, anyway. If my move is wrong; I’ll be the first one to know it.’

“Anyway, McCarthy is vastly more excited about another development in the Red Sox camp. He’s babbling, almost, about the showing of Stan Spence as his first baseman. The former Washington outfielder who hasn’t played more than 50 games at first base in his big league career, is now the sensation of Sarasota and has the first base job all to himself.

“McCarthy handed Spence a first baseman’s mitt the first day he reported, and now he’s ready to open the season with him. In fact, Murrell Jones, the Boston first baseman of last season, has seen so little action in the exhibition games that he’s about to ask somebody to introduce him to McCarthy so his presence in camp can be noted.”15

Spence got off to a slow start so on April 29 Jones replaced Spence in the fourth inning, and though Jones hit a two-run homer, neither he nor Spence could make a bold enough statement with the stick. On May 8 the Lowell Sun wrote:

“Baseball fans are all talking about the strange case of Jake Jones. This big, curly-haired first sacker has become a real problem. Lately the fellow has looked helpless at the plate. It seems that he couldn’t hit his mother-in-law with a base fiddle at two paces. Yet, he can stretch like a rubberneck at a burlesque show when it comes to playing first base.

“Time and time again Jake’s two-way stretch puts a girdle to shame as he makes almost impossible double plays. He saves his infielders errors at least twice a game, yet he is as lost as a two-year-old in a subway when he gets to the plate.

“Jones has become a real problem. Stan Spence opened the season at first base but he isn’t half as fancy around the cushion as Jake. They are both hitting at a tremendous .222 clip….”

With Boston’s record being 12-17 on May 25, McCarthy gave rookie Billy Goodman the first baseman’s mitt. Spence moved to the outfield, where he sometimes hit cleanup between Williams and Stephens, and Jake rode the pine, remaining with the club all year but seeing virtually no action in the second half of the season. He did receive a full player’s share of second-place money, $1,191.71, and in January of 1949 was released to Louisville of the American Association.

Jones played that one last season, hitting .243 with 18 homers and 69 RBIs for Louisville and then San Antonio in the Texas League. He returned to his hometown, where he owned a 400-acre cotton farm and operated a flying service, doing mostly crop-dusting work. He was recalled to active duty during the Korean War, and helped train pilots. Married twice and having raised five children and two stepchildren, Jones passed away in a local hospital in nearby Delhi, Louisiana, on December 15, 2000, at the age of 80. His widow, Mary, and son Chris were interviewed for this story. They said that Murrell was a quiet man who didn’t like publicity. He wouldn’t initiate conversation regarding baseball or the war, but didn’t shy away from either topic if asked. He continued to fly without incident until, to the great relief of his wife, he gave it up in 1980. Not unexpectedly, Jake and Ted Williams, sharing mutual interests in flying, baseball, and fishing, were great friends. Ted once forgot to return some borrowed fishing tackle and that gave Jake a story that he would use for the rest of his life — not that he didn’t have plenty of his own — as he jokingly told his friends that the great Ted Williams still owed him fishing equipment.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. The Sporting News. May 7, 1947.

2. Ibid. June 25, 1947.

3. Unidentified clipping in Jones’s Hall of Fame file.

4. Chicago Daily Tribune. November 28, 1941.

5. The Sporting News. August 23, 1941.

6. The article had originally appeared in the US Naval Institute Naval History Magazine. Williams died in 1990.

7. Syracuse Herald-American. September 8, 1946.

8. From the history of the 39th Bomb Group. WWW.39th.org.

9. The Sporting News. October 30, 1946.

10. Retrosheet.

11. SABR’s Tattersall/McConnell Home Run Log. As provided by David Vincent.

12. Lowell Sun. September 13, 1947.

13. Ibid.

14. The Sporting News. December 17, 1947.

15. Washington Post. March 30, 1948.

Additional sources

Interviews with Mary Jones and Chris Jones

Aviation and Military Museum of North Louisiana.

Full Name

James Murrell Jones

Born

November 23, 1920 at Epps, LA (USA)

Died

December 13, 2000 at Delhi, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.