Vic Janowicz

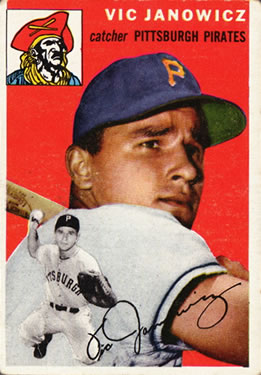

Vic Janowicz was the first winner of college football’s Heisman Trophy to play major-league baseball. He should have stuck to football. “He’s all right carrying the baseball, but he can’t throw it or hit it,” an unidentified Pittsburgh Pirates teammate said.1

Vic Janowicz was the first winner of college football’s Heisman Trophy to play major-league baseball. He should have stuck to football. “He’s all right carrying the baseball, but he can’t throw it or hit it,” an unidentified Pittsburgh Pirates teammate said.1

Janowicz gave up baseball after two futile seasons and moved on to the National Football League, where his promising career was ended by a devastating car wreck. It was not the last tragedy in his life.

For his first 22 years, he was a Golden Boy. Victor Felix Janowicz was born in Elyria, Ohio, on February 26, 1930, the eighth of nine children of Polish immigrants Veronica (Mujwit) and Felix Janowicz, a steelworker. He made all-state in football, baseball, and basketball at Elyria High and was captain of all three teams in his junior and senior years with grades that qualified him for the National Honor Society.

Several major-league baseball clubs offered contracts, and at least 60 colleges recruited him to play football. “I had been offered almost anything I wanted by certain colleges,” Janowicz said later.2 A wealthy Ohio State booster, real estate developer John W. Galbreath, courted Vic and his parents. Shortly before graduation, Galbreath sat down with the family, the high school coach, and the school superintendent to make his pitch.

“I told him I wanted it understood from the beginning that I wasn’t offering him money,” Galbreath said. “But I promised him that if he came to Ohio State and broke his leg and never played a day of football for Ohio State he would still graduate from college if he would just work for me.” Rumors circulated that the tycoon had given Janowicz a $300-a-month allowance and a new convertible, but Galbreath insisted he paid the boy by the hour for his part-time job and only lent him money to buy a used car so he could get to work.3

In his first varsity season, as a sophomore in 1949, Janowicz played primarily on defense at safety. He intercepted a pass in the Rose Bowl to set up a touchdown as Ohio State defeated California, 17-14.

Coach Wes Fesler put the 5-foot-9, 185-pound junior at tailback in the single-wing offense in 1950. He continued to play regularly on defense and also did the punting and placekicking.

Janowicz enjoyed his signature moments on two Saturdays that live in Buckeye lore. Against Iowa on October 28 in Columbus, he boomed the opening kickoff beyond the end zone. On Iowa’s first play from scrimmage, Janowicz recovered a fumble and four plays later ran for the Buckeyes’ first touchdown. He kicked the extra point. After another kickoff through the end zone, he returned a punt 61 yards for a TD and kicked the extra point. On Iowa’s next possession, he recovered another fumble, threw a touchdown pass, and kicked the extra point. The game was 5 minutes and 10 seconds old, and Janowicz led Iowa, 21-0. He went on to score 46 points in an 83-21 rout.

The Saturday after Thanksgiving brought the annual showdown with Michigan, a game immortalized as the Snow Bowl. The two archrivals played, unwisely, in a blizzard at Columbus — 28 mph winds, 10-degree temperature, and thick, blowing, blinding, unceasing snow. “My hands were numb and blue,” Janowicz said. “I had no feeling in them and I don’t know how I hung onto the ball.”4 His field goal gave Ohio State its only points. Michigan players protested that the kick was no good, but the officials, peering through the swirling snow, guessed that it passed between the uprights. Two of his punts were blocked, leading to a Michigan safety and the game’s only touchdown. The teams exchanged punts throughout the second half, often on third down, as Michigan survived to win, 9-3, and punch a frozen ticket to the Rose Bowl.

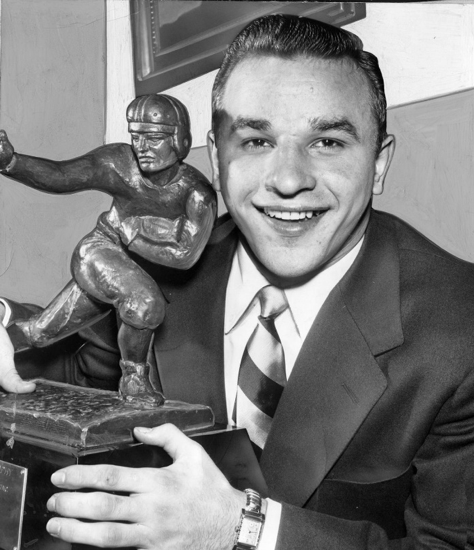

Ohio State finished with a lackluster 6-3 record, costing Coach Fesler his job, but Janowicz’s all-around excellence earned him the Heisman as college football’s best player. His stats didn’t dazzle: 703 total yards in nine games, 2.8 yards per carry rushing, and 32 completions in 77 passes. That was just a small part of his game; he was a throwback to the 60-minute two-way stalwarts of yore. The Associated Press named him a first-team All-American on defense. The Columbus Dispatch said Janowicz “did everything a football player could possibly do.”5 The Heisman vote wasn’t close; sportswriters gave him 633 points to 280 for the runner-up, Southern Methodist halfback Kyle Rote.

Janowicz’s senior year was an anticlimax. A new coach, Woody Hayes, installed the T-formation offense with Janowicz at left halfback. Although he kicked game-winning field goals against Northwestern and Pitt, injuries limited his playing time. He scored just one rushing touchdown and passed for two. There were reports of “off-the-field antics” as well.6 Stanley Frank of the Saturday Evening Post alibied that the young man was “blowing off steam” after being raised by strict parents.7

After Ohio State’s season ended, he was named the outstanding player in the Shrine East-West college all-star game, scoring a touchdown and kicking a field goal to lead the East to a 15-14 victory.

The Washington Redskins chose Janowicz in the NFL draft, but not until the seventh round, with the 79th pick. He fell so far because his Ohio National Guard unit had been called to active duty in the Korean War.

His patron John Galbreath, who owned the Pirates, persuaded him that baseball promised a better future than the NFL. Janowicz had played only one college baseball game because the season conflicted with spring football practice. When the Army sent him to Camp Polk, Louisiana, he joined the baseball team as a catcher. A right-handed batter, he hit .356 in 61 games. He got time off to play in the 1952 College All-Star football game in August, where he scored the collegians’ only touchdown and kicked the extra point in a 10-7 loss to the NFL Los Angeles Rams.

After the game, Janowicz confirmed that he was finished with football: “Only one thing would prompt me to go into professional football. That would be if I found out next spring that I have no future in baseball.” He said his boyhood dream had been to play football for Ohio State and to play major-league baseball.8

Galbreath had his protégé work out for Pittsburgh general manager Branch Rickey, who gave his seal of approval. Why fight it if the boss wanted to spend money? As soon as Janowicz was released from active duty in December, he signed for a $10,000 bonus. It was reported to be $25,000, but Janowicz gave the lower figure.

Galbreath had his protégé work out for Pittsburgh general manager Branch Rickey, who gave his seal of approval. Why fight it if the boss wanted to spend money? As soon as Janowicz was released from active duty in December, he signed for a $10,000 bonus. It was reported to be $25,000, but Janowicz gave the lower figure.

Rickey said he hadn’t been so excited by a young player since he signed Jackie Robinson and Billy Loes for the Dodgers: “I am betting on his mind, body and spirit, rather than his natural abilities, to become a real star.”9 The old Mahatma had developed a taste for what are now called “toolsy” players like Robinson, gifted athletes who had excelled in other sports but had limited baseball backgrounds. Duke basketball star Dick Groat had just finished a successful rookie year as the Pirates shortstop (and was promptly drafted into the Army), and the club had signed Dick Hall, a football, basketball, and track standout at Swarthmore.

Soon after signing Janowicz, the Pirates landed Eddie and Johnny O’Brien, twin basketball stars from Seattle University. A new bonus rule required players who had received more than $4,000 to stay on the major-league roster for two years, so Pittsburgh would be carrying three rookies with no professional experience. They could hardly drag down a team that had lost 112 games in 1952.

The Pirates sent the bonus babies to their minor-league camp for the last two weeks of spring training to get more at-bats. When the 1953 season opened, the trio sat for the first month. Then the O’Brien twins became the club’s usual double-play combination, with Eddie at short and Johnny at second. Janowicz didn’t make his debut until the end of May, when he pinch-ran.

He got his first start on June 6 against Cincinnati and grounded out in his first at-bat. He left the game in the fifth inning after the Redlegs’ Andy Seminick plowed into him on a play at the plate, but was back in the lineup the next afternoon.

Pittsburgh had just traded regular catcher Joe Garagiola in a 10-player deal that sent the club’s biggest star, Ralph Kiner, to the Cubs, so the job was wide open. Janowicz wasn’t ready. He started 32 games, striking out in one-fourth of his plate appearances while batting .252 with a .628 OPS and just six extra-base hits. Clearly his future was not behind the plate. In 35 total games, he was charged with eight errors and seven passed balls, allowed 11 wild pitches, and threw out only 4 of 18 base stealers.

After winter ball in Mexico, Janowicz switched to third base in 1954. He couldn’t field that position, either. And his bat disappeared; batting .100 and rarely playing, he acknowledged in June that he was considering pro football: “I love baseball better than football but apparently I’m not making the grade.”10 The Pirates gave him a chance to play regularly for three weeks in July, with little sign of improvement.

In mid-September Janowicz was hitting .151/.235/.192 in 84 plate appearances when he left the club to join the Redskins, but he wasn’t admitting defeat. He planned to return to baseball in the spring and go to the minors when he completed two years on the roster. Rickey said, “We have definitely not given up on this boy.”11

After three years away from football, Janowicz was slotted at defensive back and placekicker for a woeful Washington team. He suffered a shoulder separation in the Redskins’ fourth game — their fourth straight defeat — and was limited to kicking for much of the season. His 21-yard field goal gave the Skins their first victory on October 21, over Baltimore.

Janowicz turned his back on baseball when Washington signed him to a two-year contract in November. Redskins owner George Preston Marshall said he had doubled the player’s $6,000 salary with the Pirates. “I guess it’s no secret that I’m happier in football,” Janowicz said. “It’s been a rough season, but I’m feeling more at home with every game and I only hope I can do the team some good.”12

He appeared to have made the right decision. Converted to offensive left halfback in 1955, Janowicz scored the first touchdown in the opening game as the Redskins upset the defending champion Browns in Cleveland to begin a startling turnaround. After finishing 3-9 the previous year, Washington rose to second place in the NFL East with an 8-4 record, the best in a decade. Janowicz was the team’s leading rusher with 397 yards, a 4.3-yard average, and four touchdowns. He caught 11 passes for three more TDs. Although he hit only six of 20 field goal attempts, his 88 points were second in the league. At 25, he looked like a rising star.

After the season he married Marianne August, whom he had met when the Redskins visited Chicago. Their daughter Diana was born in June 1956. Two months later doctors told Marianne that the baby had cerebral palsy. Vic was in California preparing for a preseason game, so she kept the news from him.

The night after the game in Los Angeles, Janowicz attended a party at the home of teammate Gene Brito. He was riding back to the Redskins’ training headquarters at Occidental College in a car driven by a 21-year-old nursing student when she fell asleep at the wheel and crashed into a utility pole.13

Janowicz suffered severe brain trauma that finished his football career. Although the Redskins paid his hospital bills, owner Marshall released him on the grounds that the injury was not football-related. “Do you realize that we’ve lost a tremendous amount of money because of this boy’s absence?” Marshall said. Janowicz’s teammates and coaches voted to contribute $10 a week each to help support him and his family.14

The injury paralyzed his left side and caused memory lapses and confusion. Ohio State’s medical staff and athletic trainers took charge of his recovery as he struggled for four years to regain full mental and physical function. During that time Marianne suffered a miscarriage, and Vic was laid off from his job on a loading dock. He took several menial jobs to pay the bills, which included huge medical costs for his daughter’s treatment. Diana died when she was 8.

Vic and Marianne had a son, Victor II, and a daughter, Jacqueline. As his physical condition improved, he worked in public relations for a manufacturing company and as a broadcaster on Ohio State football games. In 1968 he was reported to be spearheading a movement to dump his former coach, Woody Hayes. “Not true,” Janowicz said, though he had used his radio show to criticize Hayes’s conservative offense, which was described as “three yards and a cloud of dust.”15

Janowicz was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1976. In 1992 a boosters organization, the Columbus Downtown Quarterback Club, named him Ohio State’s greatest athlete of the half-century. He battled prostate cancer for the last several years of his life and died on February 27, 1996, the day after his 66th birthday.

Acknowledgements

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Milton Gross, “What They’re Saying Over the Bat Racks,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1954: 12.

2 Les Biederman, “The Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, March 1, 1953: 4-1.

3 Ken Davis, Associated Press, “Galbreath Insists Janowicz Works for Any Money He Gets,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, January 14, 1951: 50.

4 “1950 Snow Bowl,” Ohio State University Monthly, https://library.osu.edu/blogs/osuvsmichigan/snow-bowl/, accessed July 2, 2018.

5 “Heisman Trophy to Janowicz,” Columbus Dispatch, December 6, 1950: 47.

6 Paul Hornung, “In the Press Box,” Columbus Dispatch, January 17, 1952: 13.

7 Quoted in Columbus Dispatch, November 13, 1951: 28.

8 Associated Press, “Janowicz Plays in Last Tilt,” Columbus Dispatch, August 16, 1952: 10.

9 Jack Hernon, “McCullough Traded; Bucs to Sign Janowicz,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 4, 1952: 22.

10 Associated Press, “Janowicz Threatens to Quit Baseball for Pro Football,” Washington Post and Times Herald, June 24, 1954: 26.

11 “Pirates Haven’t Given Up on Janowicz, Rickey Says,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1954: 15.

12 Shirley Povich, “Janowicz to Quit Bucs for Gridiron — Marshall,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1954: 9.

13 “Redskins Star Janowicz Hurt in Car Crash,” Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1956: 1.

14 Jack Walsh, “Coaches Also Join in Donations,” Washington Post and Times Herald, October 10, 1956: 55.

15 Bill Beck, “Lost Years for Janowicz,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 6, 1968: 3-C.

Full Name

Victor Felix Janowicz

Born

February 26, 1930 at Elyria, OH (USA)

Died

February 27, 1996 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.