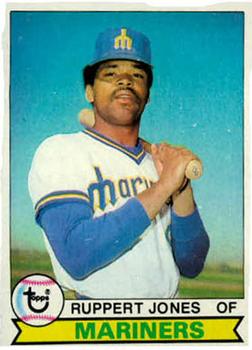

Ruppert Jones

If a movie of Ruppert Jones’s career were to be made, its title might be What Could Have Been. This gifted five-tool player was beset by injuries throughout his career. He could hit with power to all fields and run like a gazelle. Jones called homers “accidents,” maintaining that he was at the plate to make contact and get base hits. He hit 147 accidents in his career. He came to Seattle from Kansas City after being the very first pick in the 1976 expansion draft. Jones was the first Mariner to be an All-Star, in 1977 and made the team again, this time for the National League, for the San Diego Padres in 1982. As a Mariner playing in front of small crowds, Jones heard the constant chants of his name: “ROOP! ROOP! ROOP!”

If a movie of Ruppert Jones’s career were to be made, its title might be What Could Have Been. This gifted five-tool player was beset by injuries throughout his career. He could hit with power to all fields and run like a gazelle. Jones called homers “accidents,” maintaining that he was at the plate to make contact and get base hits. He hit 147 accidents in his career. He came to Seattle from Kansas City after being the very first pick in the 1976 expansion draft. Jones was the first Mariner to be an All-Star, in 1977 and made the team again, this time for the National League, for the San Diego Padres in 1982. As a Mariner playing in front of small crowds, Jones heard the constant chants of his name: “ROOP! ROOP! ROOP!”

Born Ruppert Sanderson Jones on March 12, 1955, in Dallas, Texas, Jones was about to become a teenager in Texas when his mother and stepfather decided to move to Berkeley, California. He didn’t want to leave. “In the ’60s, black folks had a better chance in California than they did in Texas,” he said. Still, it was hard for Jones to make friends at Berkeley High School. “I was a country boy living in the city, different than everyone else,” he said. “What acceptance I got, I earned on the playing field.”

In his senior year at Berkeley High, he batted .457 with seven home runs, was unanimously named to the All-Alameda County League and All-East Bay teams, and was an All-Northern California selection. In addition to his baseball skills, he was a unanimous choice for All-East Bay honors in football, as a defensive back, and basketball, as a guard. He helped lead Berkeley to two Northern California football titles and helped lead the basketball team to the league championship and second place in the Bay Area’s Tournament of Champions in his senior year, earning All-State honors in both sports. It was little wonder that he was voted the East Bay Athlete of the Year for 1972-73. He played in the same outfield at Berkeley High with future major leaguers Claudell Washington and Glenn Burke. Jones received scholarship offers to play football at Oregon State, Arizona State, and California, but focused on baseball because he was a better outfielder than wide receiver. He signed with the Kansas City Royals, who chose him in the third round of the June draft in 1973 and signed him for $22,000.

After being signed by scout Dick Hager, Jones reported to Billings of the Pioneer League, where he batted .301 with four homers and 31 RBIs in helping the Mustangs win the pennant, and was named to the league’s All-Star team. It was on to Waterloo of the Midwest League in 1974. On July 11, he was promoted by Kansas City to the San Jose Bees of the California League. When he left Waterloo, he was pasting the ball for a .353 batting average on 88 hits, and was second in the league with 13 homers and 43 RBIs. Jones was 41 points ahead of his nearest rival for the hitting title, in a ten-club circuit with only ten batters over the .300 mark. After joining the Bees he was blanked in his first four times at bat, but came back the next night and homered and doubled to drive in two runs to help San Jose beat Bakersfield, 9-8. Between the two teams he hit 21 homers and drove in 88 runs.

The next two years were spent in Triple-A playing for Omaha of the American Association. It did not come as easily as the previous two years for Jones. He hit .243 in 1975 with 13 homers and 54 RBIs. But 1976 saw Jones rebound to have a solid year. In 102 games he blasted 19 homers, drove in 73 runs, and hit .262 before being called up by the Royals late in the season. He struggled a little after the call-up, getting into 28 games but hitting just .216 with one homer. His first major-league hit, a single, came off future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry in his very first at-bat, on August 1, 1976, as the designated hitter against the Texas Rangers; he collected a run and an RBI on a 1-for-4 day. After just 51 at-bats, though, his time with the Royals was over. The Royals’ decision not to protect Jones was difficult, but they believed they needed to protect outfielder Willie Wilson and shortstop U.L. Washington, thereby leaving Jones exposed. He was made the first pick in the 1976 expansion draft by Seattle. Danny Kaye, the comic actor and part-owner of the Mariners, was summoned by Lee MacPhail to make the first selection, and Kaye called out the name of Ruppert Jones.

To say that Jones was a hit in Seattle in 1977, the Mariners’ first season, would be an understatement. He was so popular that he could have run for mayor. It started with the center-field fans, Roop’s Troops, and spread throughout the Kingdome. Jones could do no wrong with the fans as they cheered his every move. As much as his offense was expected and talked about, it was his defense that was drawing raves from fans and management. Each time Jones stepped to the plate the Kingdome crowd would ring out with chants of “Roop, Roop, Roop.” At the plate he did not disappoint in his rookie season, hitting .263 for the year even though his impatience showed at times. He played in all but two games and was second on the team in homers with 24. He also led the team in strikeouts with 120, but finished third on the team with 76 RBIs. Unfortunately, Jones experienced the ugliness of racism, being stopped four times while driving his Mercedes-Benz. Jones said troopers just couldn’t understand how a young black man could afford such a vehicle.

What happened after the season was the only thing that plagued Jones’s career: injuries. After the season he underwent the first of his many surgeries, having torn cartilage removed from his left knee.

The 1978 season was a step back for Jones, as he struggled to recover fully from the surgery. If that wasn’t bad enough, he had an emergency appendectomy in June and lost 15 pounds and missed a month of the season. He slipped across the board from 1977, hitting just .235 with six homers and 46 RBIs. Though his offensive production fell, Roop’s fielding did not suffer. He kept making remarkable catches. “In some ways,” he said, “it was a good year for me. I learned something about myself, my character. I didn’t give up; I didn’t let my slump bother my fielding.”

Jones spent some time that year as a sportscaster. He worked for a black radio station in Seattle, KYAC, which used Jones’s taped interviews with ballplayers for its sports show.

Jones rebounded to have his finest season in 1979, playing in every game and establishing career highs in runs (109), RBIs (78), hits (166), triples (9), and stolen bases (33). He attributed his success to a new offseason workout regimen.

The season was so good that Jones became the hot player talked about in almost every trade scenario. One scenario wasn’t fiction: He was traded to the New York Yankees on November 1, 1979, with pitcher Jim Lewis, for four players: outfielder Juan Beniquez, catcher Jerry Narron, and pitchers Jim Beattie and Rick Anderson. The Yankees needed a center fielder and loved Jones’s potential and his ability to chase down the ball in the outfield with the best of them. “I had a dream the week before I was traded,” Jones explained in the stadium pressroom. “I dreamed of myself in a Yankee uniform. I knew I was going to be traded. I thought I would go either to the Dodgers or the Yankees, but in my dreams I only saw myself as a Yankee.” Most scouts agreed that Roop was a top-flight player who would get better in a winning environment. In three years at Seattle, his steals went from 13 to 22 to 33. He hit the first inside-the-park homer at the Kingdome, which was like running one out in a phone booth.

As excited as Jones was to become a Yankee, his dreams soon became a nightmare. He started 1980 slowly, batting .222 through May 26 with only five homers before the first of two trips to the disabled list. During the May 26 game, he had a stomachache and later that night at a barbecue at the home of Willie Randolph he continued to complain about it. Later that evening he was rushed to emergency surgery at Pascack Valley Hospital in New Jersey, for removal of an adhesion that had caused an intestinal obstruction. The adhesion was believed to be the result of the previous year’s emergency appendectomy. Jones missed six weeks of action. Then, after coming back from surgery, he separated his shoulder on August 25, running head-first into the center-field wall at the Oakland Coliseum while attempting to catch a first-inning fly ball hit by the A’s Tony Armas. Jones missed the rest of the season, winding up with the lowest full-season average of his career at .223 and only nine homers.

Jones remembered standing in center field in Oakland that August evening with two runners on base in the first inning. With Tommy John pitching, Armas powered the ball toward left center, and Jones ran to make the catch.

The next thing Jones remembered, he was waking up in the hospital 24 hours later with a concussion and a separated shoulder. “People tell me what happened,” Jones said, “but there’s a whole night of my life I don’t remember. Initially, I was just grateful I was still alive. When I woke up feeling somewhat fine and alive, I was relieved.”

Jones said he was more depressed after his abdominal surgery to remove the blockage in his intestine than after his shoulder injury. “The nurses would speak to me,” said Jones, “and I’d just grumble and mumble. I always had a stern look on my face and they said they were scared of me.” After a few days of feeling sorry for himself, Jones, ordinarily cheerful, paid a visit to the pediatric ward. There, he saw children “screaming in pain” and others “bald from the chemotherapy.”

“That really woke me up,” Jones said. “Those kids had so much courage. They would never have the opportunity to do what I had done, so what was I complaining about?”

What was supposed to be the start of long career as a Yankee ended after just one year. On March 31, 1981, late in spring training, Jones was shipped out along with Tim Lollar, Chris Welsh, and Joe Lefebvre to the San Diego Padres for Jerry Mumphrey and John Pacella.

Looking to shake off 1980, Jones headed to San Diego in ’81 looking to get back to the form he had with the Mariners. He did not quite bounce back as he had hoped, hitting just .249 with four homers and 39 RBIs. But the following year showed a return to Jones’s early years in Seattle.

Jones made a commitment to really work on his health and train harder than ever before. He did a lot of physical conditioning and worked on his swing mechanics. Living in San Diego, he worked on baseball instead of just working out. Before, he was in Washington state and New Jersey, where it’s cold and rainy for much of the offseason. He hit about 450 balls a week off a batting tee.

The work paid off in 1982, as Jones became an All-Star for the second time in his career. After playing 32 games, he was hitting .328 with five homers and 19 RBIs. A week later he had pushed up his average to .357 with 25 RBIs, and was among the league leaders in several categories. Because of his red-hot start he became a hero of the left-field bleacherites at San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium. Ruppert brought out his old Roop’s Troops slogan and it was made into T-shirts for his crew. And while the Padres center fielder enjoyed the enthusiasm of his “Troops,” he wouldn’t let it go to his head. He didn’t believe in statistical goals, but instead kept one simple goal in mind: to be the best ballplayer he could be every day. “Dick Williams, manager of the Padres, said something to me that I’ve always believed,” said Jones. “He said to beat your opponent any way you can; get them with your glove or baserunning if you can’t get them with your bat. Coming from someone with his experience, especially from a winner, just reinforced it.”

In the All-Star Game, Jones batted in the third inning, pinch-hitting for Montreal hurler Steve Rogers, and stroked a triple off the wall in right-center, later scoring. He went on to hit .283 for the year with 12 homers, 18 stolen bases, and 61 RBIs. What hurt Jones, again, was another injury, two weeks after the All-Star break. He twisted his ankle, missed almost a month, and was never the same with the Padres after that. He played just one more year with San Diego, batting .233 with 12 homers and 49 RBIs in 1983.

Granted free agency on November 7, 1983, Jones found no takers, so he headed to camp with the Pittsburgh Pirates and hit .370 during spring training, but was released on the final cut. He found no takers except for Detroit Tigers general manager Bill Lajoie, who liked the thought of Jones hitting into the right-field seats and signed him on April 10, 1984. But first he was sent to Evansville, the Tigers’ Triple-A club, before getting a second chance. His chance came in early June, when he was called up. He hit a three-run homer in his second game back to beat Toronto 5-3. Jones hit five homers and batted .283 in his first 20 games back. He platooned with Larry Herndon for the remainder of year, ending the season with 12 homers, 37 RBIs, and a .284 average. Four of his home runs either won a game or put the Tigers in the lead for good. Jones hit two rooftop homers in a ten-day span. First he became the 13th player to hit one over the right-field roof at Tiger Stadium, off the third deck in right field, which prompted Tigers fans to dub him Rooftop Jones. He then hit one on top of the roof at Comiskey Park. By then Detroit fans had warmed up to Jones, chanting his name, “Roop, Roop.” “I’m enjoying this, mostly because of the adverse circumstances I went through,” Jones said. “It takes a lot of support to bring in a new player into a situation of this magnitude, when nobody else was willing to bring me into any situation, let alone a winning one. I’m not bitter about what I went through, however. All good things happen for a reason.”

The Tigers went on to win the World Series by beating the San Diego Padres, Jones’s former team. He saw limited action, getting three at-bats with no hits, but he did get a ring. At the end of the season, on November 8, he was granted free agency, and this time the California Angels signed him on January 30, 1985.

Jones rebounded in California to hit 21 homers and drive in 67 runs in 125 games. The Angels signed him once Fred Lynn left via free agency for Baltimore, and Angels manager Gene Mauch was thrilled. “Oh boy, has he helped us,” said Mauch. “We got him as an insurance policy, but he’s sure paid off.” Jones continued to hit the long ball in 1986, smacking 17 home runs and knocking in 49 runs, though he batted just .229. He was back in double figures with 10 steals. He continued to be a very good outfielder, moving from center field to spending most of his games in right field.

Jones played in just 85 games in 1987, batting .245 and hitting eight homers. After the season, he was released. He had played his last major-league game.

Jones signed a free agent contract on February 27, 1988, with the Milwaukee Brewers, who were looking for a left-handed pinch-hitter and occasional designated hitter. He was battling Jim Adduci for the final roster spot. He batted .361, in spring training but was unable to play in the field because of a shoulder injury. The Brewers released him before the season began. In May he was picked up by the Texas Rangers and assigned to their Triple-A farm club, the Oklahoma City 89ers. He got into 50 games there, batting .253 with 7 homers and 30 RBIs. He left halfway through the year to join the Hanshin Tigers of Japan’s Central League. There he played in 52 games with 8 homers, 27 RBIs, and a .254 average. He signed a minor-league contract with Texas in May 1989 for one more try to get back to the majors. It lasted 27 games at Oklahoma City before Jones called it a career after hitting just .200 with one homer in 80 at-bats. He was 34 years old and had been playing professionally for 17 years.

In his career, Jones batted .250 with 147 home runs, 579 RBIs, 643 runs, 215 doubles, 38 triples, and 143 stolen bases. Two of his biggest hits came against Hall of Famer Dennis Eckersley. On June 3, 1977, at the Kingdome in Seattle, Jones hit a home run to right field in the sixth inning to end Eckersley’s streak of 22? consecutive hitless innings over parts of three games, two outs short of Cy Young’s record. (Eckersley was with Cleveland at the time.) In the 1982 All-Star Game, he hit a triple off Eckersley, then with the Boston Red Sox. “What could have been” will be the legacy of one Ruppert Sanderson Jones.

In his 50s, Jones was selling insurance in the San Diego area and spending time with his family, playing golf, and reading fiction, especially Robert Ludlum and John Grisham. He learned to like sales. “I don’t have a college education,” he said, “so the satisfaction is making a success in something other than athletics.”

Sources

Publications

Baseball Register (1977-1988).

San Diego Padres yearbooks, 1982-84.

Seattle Mariners yearbooks, 1978-80.

Naiman. Joe, and David Porter. The San Diego Padres Encyclopedia.

Articles

Moore, Jim. “‘Roop!’ still echoes in Mariners lore.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 6, 2001.

Ruppert Jones clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

The Sporting News: January 19, 1976, p.44; August 21, 1976, p.9; October 2, 1976, p. 33; November 20, 1976, p.34; November 27, 1976, p.48; December 18, 1976, p. 49; April 2, 1977, p.11; December 31, 1977, p.62; January 28, 1978, p.59; June 30, 1979, p.43; February 9, 1980, p.36; July 11, 1981, p.36; May 31, 1982, p.17; June 7, 1982, p.36; June 28, 1982, p.22; July 12, 1982, p.28; July 26, 1982, p.26; September 20,1982, p.43; August 16, 1982, p.37; July 9, 1984, p.28; March 16, 1987, p.33; March 14, 1988, p.37; April 11, 1988, p.31, May 16, 1988, p.22, May 1, 1989, p.52.

Websites

http://minors.sabrwebs.com/cgi-bin/player

http://www.baseball-almanac.com

http://www.baseball-reference.com

http://www.1984tigers.com

http://www.paperofrecord.com

http://www.retrosheet.org

http://www.timesnewsweekly.com

Full Name

Ruppert Sanderson Jones

Born

March 12, 1955 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.