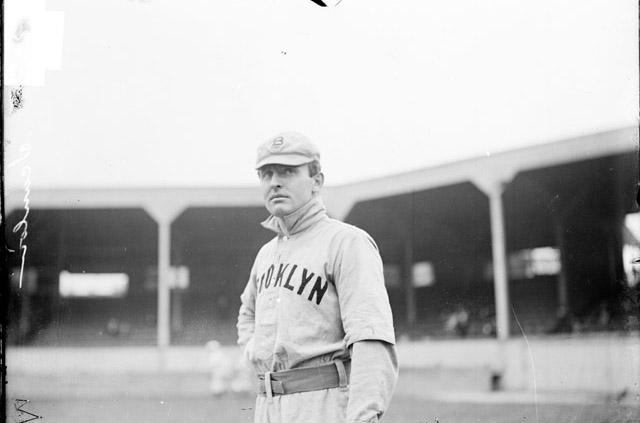

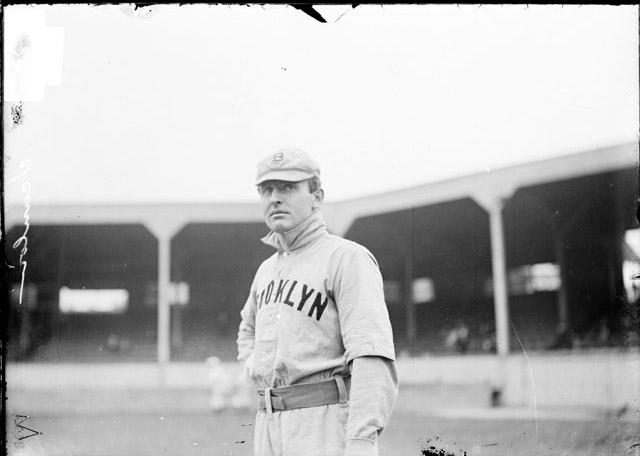

Doc Scanlan

During the winter of 1911-1912, Dr. William D. Scanlan was obliged to make a life-altering decision. For the past seven years, he had been a pitching mainstay for the woeful Brooklyn Superbas. But during that same period, Doc Scanlan had also completed his medical studies, satisfied New York state licensing and internship requirements, and begun establishing a private patient practice in Brooklyn’s tony Park Slope neighborhood. Then a trade to the Philadelphia Phillies required him to make a choice: baseball or medicine?

Only 30 and still in his hurling prime, Scanlan very much wanted to continue pitching, particularly for a competitive team for a change. But relocation to Philadelphia would have necessitated the uprooting of his young family and abandoning the medical practice that he was building. In the end, Scanlan chose medicine, remaining in Brooklyn and establishing a thriving hospital and office practice. Yet he managed some pitching, too, throwing weekend games for prominent area semipro ball clubs into his late 30s. By the time of his death in 1949, Doc Scanlan had enjoyed the best of life: the thrill of major league baseball, the fulfillment of medical practice, and the rewards of a happy family. The story of this semi-charmed life follows.

The Scanlan saga begins in Syracuse, New York, with prosperous merchant Dennis Scanlan (1851-1916) and his wife Bridget (née Ryan, 1858-1919), both natives of Ireland brought to America as toddlers. In time, the couple met, married, and started a family which ultimately included ten children.1 Oldest son John (born 1879) left school after completing the eighth grade and spent most of his working life as a city fireman. But his four younger brothers (Doc, Ray, Ambrose, and Frank Scanlan) all attended Syracuse High School and then went to college, as did four of the Scanlan sisters, highly unusual for the time. In the case of Frank and Ambrose, however, furthering their education seems merely to have provided cover for developing their athletic skills. Both were left-handed pitchers who aspired to be professionals.2 But the star ballplayer of the family was unmistakably Doc, or Billy as he was called early in his career.

Born March 7, 1881, William Dennis Scanlan was educated in local parochial and public schools through high school graduation. All the while, hometown Syracuse was a hotbed of sandlot, amateur, and professional baseball and had briefly been the home of major league clubs in the National League (1879) and American Association (1890). Like other athletically gifted youths, Billy gravitated toward the diamond and soon developed into a first-rate right-handed hurler, pitching for local amateur and church league clubs. Although not of imposing size – eventually 5-foot-8, 165 pounds – Scanlan started out as a power pitcher, relying on a high fastball as his out pitch.

A serious student but a restless one, he spent his first two collegiate years (1898-1900) downstate at Manhattan College. He then transferred to Fordham University for his junior year (1900-1901), before spending the summer pitching for the Ogdensburg club of the unclassified professional Northern New York League. There, Scanlan attracted attention in a July exhibition contest by throwing a one-hitter with 11 strikeouts. The 3-1 victory came against no less than the National League pennant-bound Pittsburgh Pirates.3 Thereafter, Billy returned home, earning his A.B. degree from Syracuse University in June 1902.4 At all three schools where he was an undergraduate, Scanlan pitched and occasionally played the outfield as well.

Following his college graduation, Scanlan returned to the Northern New York League, pitching for a club in Canandaigua. He entered Organized Baseball in July 1902, signing with the Ilion Typewriters of the Class B New York State League.5 He helped pitch Ilion to a third-place (59-47, .557) finish in NYS League final standings. Scanlan returned to Ilion for the 1903 season and remained there until claimed by the Pittsburgh Pirates, his 1901 exhibition game victim, in the September minor league player draft.6

Billy Scanlan made his major league debut on September 24, 1903, in a home game against the Giants. His opposite number was former Ilion pitching mate Red Ames. In a complete-game effort, Scanlan held the Giants to five hits but was undone by eight walks, a harbinger of the control problems that would plague him in future. A four-run Giants uprising in the ninth inning saddled the youngster with a misleading 7-2 defeat. After the game, press reviews decried the wildness of the rookie pitchers – Ames walked six batters himself – but were generally positive. “Scanlon was beaten but not disgraced,” observed the Pittsburg Press, establishing precedent for the career-long misspelling of the pitcher’s surname.7 “For he pitched magnificent ball, aside from his wildness, allowing the hard-hitting Giants but two hits in [the first] eight innings.” Both he and Ames, who struck out seven, “used their heads well, and many batters fanned the air.”8 Also favorably impressed was the Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, which dismissed Scanlan’s control problems as first-game nerves, only regretting that the Pirates had not secured him in time for him to be eligible to play in the upcoming World Series.9 While the Pirates were being upset in the first modern Fall Classic by the Boston Pilgrims of the upstart American League, Scanlan began preparation for his ultimate profession, enrolling in the Long Island College of Medicine.

After an offseason Pittsburgh-Ilion dustup over payment for Scanlan was resolved,10 he was back in Pirates livery for the 1904 season. But Scanlan pitched poorly, going 1-3 in four outings, while walking 20 in only 22 innings pitched. In late June, he drew his unconditional release.11 Back home in upstate New York, Billy spent the next six weeks playing for the Plattsburgh club in the unrecognized Hudson River League.12 By early August, however, he was back in the National League, signed by Brooklyn Superbas field manager/club co-owner Ned Hanlon.13 There, he regained form. In 13 appearances, he posted a 6-6 record with three shutouts for a lousy 56-97-1 (.366) Brooklyn team. Over 104 innings, Scanlan reduced his walks total to 40 while striking out a like number of enemy batsmen and registering an excellent 2.16 ERA.

Scanlan established himself as a bona fide major leaguer in 1905, ending his season with an ironman feat: complete-game doubleheader victories over the St. Louis Cardinals, 3-0 and 7-2. Working for a hapless Brooklyn club that otherwise went 34-92-2 (.270), he posted a winning 14-12 (.538) record, leading the staff in victories, ERA (2.92), and strikeouts (135), as well as walks (104), in 249 2/3 innings pitched.

During the offseason, simmering ill-will between Scanlan and Superbas management became public. It had been present since the year before, when Scanlan felt himself shortchanged in dealings with Hanlon,14 This time, both Scanlan and club president Charles Ebbets disputed each other’s representations regarding the pitcher’s salary.15 After a brief holdout, Scanlan agreed to terms for the 1906 season. But his resentment endured, and by late May he had commenced taking the first of the examinations needed for licensure by state medical authorities.16

Over the short term, however, the would-be physician concentrated on baseball. Pitching for another substandard 66-86-1 (.434) edition of the Superbas, Scanlan went 18-13 (.581), posting the staff’s only winning record. In addition to a career-best in wins, Scanlan also set personal top marks for complete games (28), innings pitched (288), and shutouts (6). On the negative side, his 127 walks issued was also a career high.

That winter, Scanlan resumed his medical school studies and intimated that he might not play ball in 1907.17 Eventually, he agreed to return to the Superbas, but would not attend spring training. Instead, he remained in New York so that he could graduate from medical school on May 1.18 Doc Scanlan made his season’s debut on May 24, notching a complete game victory over the Philadelphia Phillies, 6-3. But the year proved a difficult one for him, both on the field and off. The medico-pitcher was dogged by health problems that eventually required a mid-season layoff with recuperation time at home in Syracuse. Logging only 107 innings in 19 appearances, Scanlan posted a disappointing 6-8 record. Far worse was on the horizon.

After the season, young Dr. Scanlon began an internship at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn. But by early December, the new physician was himself a hospital patient. On the evening of December 5, 1907, he underwent an emergency appendectomy, high-risk surgery at the time. “Close Call from Death for Pitcher Dr. Billy Scanlan” was the headline of the Brooklyn Citizen’s account of the successful surgery.19 The patient recovered slowly and remained hospital-bound until mid-January. “For a time I thought myself I would never pull through, but I was fortunate in having the best of care, and I owe a great deal to Dr. Albers, surgeon of the hospital,” Scanlan said upon his discharge from care.20 Two months later, Scanlan was still recuperating, and it was “much to be doubted that he will undertake the arduous work of pitching this season.”21 In time, Dr. Scanlan recovered sufficiently to resume his hospital internship, but he did not throw a single pitch for the Brooklyn Superbas during the 1908 season.22

After sitting out the 1908 campaign, Billy Scanlan, now more often called Doc, contemplated a return to the Superbas. He had completed his internship at Kings County Hospital while recuperating, and in January 1909 he accepted the position of house surgeon at the hospital. But that winter Scanlan also announced that he would “accept the [contract] offer Ebbets made to him” for the coming baseball season.23 Still, Scanlan remained a handful for club management. He agreed to sign – provided Ebbets allowed him to attend to his hospital duties through February, and then vacation at home in Syracuse. Only thereafter was the doctor willing to report to spring training in Florida.24 Desperate for pitching, the club owner capitulated to Scanlan’s demands.

Upon his return, Doc was no longer the power pitcher he had been before his hospitalization. Now he frequently changed speeds and had added a spitball to his repertoire.25 Once the season commenced, Scanlan was used judiciously, making only 19 mound appearances. But as before, he was much better – 8-7 (.533), with a 2.93 ERA in 141 1/3 innings – than the 55-98 (.359) Brooklyn club for which he toiled. After his season’s work was done, he effected a change in his domestic situation. On November 15, 1910, Dr. William D. Scanlan married Utica school teacher Helen Tanner. Upon their return from a honeymoon in Florida, the newlyweds took up residence in Brooklyn, where Scanlan was beginning to establish a private medical practice.

Doc Scanlan struggled at times during the 1910 season but finished strong, winning five of his final six pitching decisions to finish the season with a 9-11 (.450) log and a 2.61 ERA in 217 1/3 innings. Per usual, these modest numbers were above the Brooklyn club norms: 64-90 (.416) with a 3.07 staff ERA. The following spring, Scanlan was a contract holdout, spending the spring in upstate New York coaching the Cornell University pitchers.26 Soon thereafter, it was reported that Scanlan might be traded.27 In the end, Doc remained Brooklyn property, but he and the club did not come to terms until after the regular season had started. Scanlan made a belated debut in 1911, notching a 2-1 win over the Cincinnati Reds on May 18 for his first victory. Five days later, he beat Pittsburgh, 4-3. Then, the “Scanlon jinx”28 descended.

Over almost the next three months, Scanlan went winless, dropping 10 straight decisions. A 10-inning, 6-5 victory over Chicago on August 24 finally snapped his losing skein, and raised his season record to 3-10. He followed that long-awaited victory with an inning of scoreless relief in a 4-2 Brooklyn loss to Boston on September 1. On that date, the Superbas had more than 30 games left on the schedule. But Doc Scanlan would not see action in any of them. Indeed, then unbeknownst to all concerned, his time as a major league pitcher had expired.

The event that finalized the end of Doc Scanlan’s days in Organized Baseball was his offseason trade to the Philadelphia Phillies. Brooklyn received young right-hander Eddie Stack in return.29 Although approaching age 31, Scanlan still wanted to pitch. But with family responsibilities that now included a newborn son and professional responsibilities to patients, he was unwilling to uproot himself from Brooklyn. In addition, Scanlan was again aggrieved by his treatment by club boss Ebbets – a dispute about withheld 1911 salary was the sore spot this time.30 Nor was he impressed by Philadelphia’s salary offer. Doc therefore refused to sign the contract tendered to him by the Phillies and remained home. His career as a major leaguer was over.

His dismal final season with Brooklyn dropped Scanlan’s career record below .500: 65-71, .478. But that was still markedly better than his non-competitive Superbas clubs. In 1,252 innings pitched, he posted a 3.00 ERA, striking out 584 but walking more, 608. His consistently good stuff was reflected in the stingy .234 batting average yielded to opposition hitters. All considered, Doc had been an above average Deadball Era pitcher.

In short order, Doc Scanlan reconciled his professional ambitions. While he set about establishing what quickly became a thriving medical practice in Park Slope, he gratified his pitching itch by hurling weekend baseball for the Ridgewoods, a top-notch semipro club in nearby Queens. Periodic rumors about his return to the majors were promptly spiked by the doctor. “I have not heard from the Philadelphia club,” Scanlan declared in July 1913. “I am perfectly satisfied with my practice and am doing nicely and am through with organized baseball. [Philadelphia manager Red] Dooin couldn’t offer me enough money to pitch for his club.”31 Thereafter, Doc continued to build his practice while pitching on weekends for various local semipro clubs. Meanwhile, he and Ebbets buried the hatchet. The Brooklyn club boss granted Scanlan the unconditional release required for removal of his name from Organized Baseball’s ineligible list.32

Ebbets’ gesture permitted Scanlan to make a one-game comeback of sorts. While back in his hometown visiting family in early July 1918, Doc Scanlan (by then 36 years old) was a surprise starter for the Syracuse Stars in an International League game against the Jersey City Skeeters. Notwithstanding age and a considerable midriff – one news account claimed that “the once great pitcher now tips the scales at close to 300 [pounds]”33 – he held the opposition scoreless before retiring after five innings.34 By then, however, Scanlan was fully engaged in his medical practice, which now included surgical privileges at four Brooklyn hospitals. He also served in the Brooklyn National Guard and had become the father of four sons.

During the 1930s, Doc balanced the demands of his medical practice with following the exploits of his offspring, all outstanding Brooklyn schoolboy athletes. In time, Billy, Bob, and Tom Scanlan followed their father into the medical profession, while John became a career military officer. Meanwhile, Doc retained his interest in the major league scene, his commentary on the fortunes of the Brooklyn ball club periodically appearing in local newsprint.35 Through it all, he kept a demanding 72-hour per week hospital/office work schedule.36

In March 1942, the death of wife Helen brought a long and happy marriage to an end. Some years later, Doc himself fell ill, afflicted with cancer.37 He spent his final months confined to bed at home, dying there on May 29, 1949. William Dennis “Doc” Scanlan was 68 and had lived an exceptionally eventful and productive life. Following a Requiem Mass said at St. Francis Xavier Church, Brooklyn, his remains were interred next to those of his wife at St. Joseph Cemetery in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In addition to his sons, the deceased was survived by his brother Frank and four of his sisters.

More than a century after Doc Scanlan made his major league debut, his memory was honored in his old hometown. In 2006, he was enshrined on the Syracuse Chiefs Baseball Wall of Fame. Four years thereafter, Scanlan was inducted into the Greater Syracuse Sports Hall of Fame. Fitting memorials both.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Warren Corbett and factchecked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information imparted above include the Doc Scanlan file with completed player questionnaire maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US and New York State Censuses and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 The Scanlan children, all of whom were relatively long lived, were Minna (Mary Ann, born 1878), John (1879), William (1881), Julia (1882), Gertrude (1883), Raymond (1886), Ambrose (1888), Frank (1890), Anna (1892), and Imelda (1901).

2 Frank, Ambrose, and catcher Ray Scanlan were teammates on the baseball team at Notre Dame, and all three later entered the professional ranks. Only Frank, a six-game pitcher for the 1909 Philadelphia Phillies, reached the majors. For more on the family, see Bill Lamb, “The Scanlan Brothers,” The Inside Game, Vol. XXI, No. 4 (November 2021).

3 “Northern New York League,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press, July 9, 1901: 2.

4 Online Syracuse University alumni directory, Class of 1902.

5 “The National Game,” Abbeville (South Carolina) Press & Banner, July 16, 1902: 3; “Condensed Dispatches,” Salina (Kansas) Union, July 26, 1902: 5; and elsewhere.

6 Dallas Morning News, September 23, 1903: 10, and Worcester Spy, September 22, 1903: 2.

7 “Youngsters Batted Hard,” Pittsburg Press, September 25, 1903: 18.

8 “Youngsters Batted Hard.”

9 See “Giants’ Twirler Won the Test,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, September 25, 1903: 9.

10 See “Players Eager for the Spring,” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, February 14, 1904: 19; “Locke Coming to See Scanlon,” Syracuse Post-Standard, January 11, 1904: 3.

11 “Pitcher William D. Scanlon Is Released by Pittsburg Club,” Pittsburg Post, June 23, 1904: 8; “Baseball Notes,” Pittsburg Press, June 23, 1904: 12.

12 See the Binghamton (New York) Press, August 4, 1904: 10.

13 “Scanlon Signs with Brooklyn,” Pittsburg Post, August 3, 1904: 6. See also, Burlington Free Press, August 6, 1904: 3.

14 For the 1905 salary dispute details, see “Brooklyn Fan the Real Scout,” Brooklyn Citizen, February 17, 1907: 5.

15 Compare “Scanlon Well Treated by Brooklyn Club; Salary Increased $600, Says Pres. Ebbets,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 7, 1906: 11, with “Pitcher Scanlon Refuses to Sign at Salary Offered by Brooklyn Club,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 5, 1906: 6.

16 Brooklyn Standard Union, May 27, 1906: 6.

17 “Pat Donovan a Past Master with the Dope,” Brooklyn Citizen, December 24, 1906: 5.

18 “Scanlon Sticks to Medicine,” Brooklyn Citizen, February 13, 1907: 5. See also, “Scanlon to Join the Superbas,” Brooklyn Times, May 13, 1907: 5, and “Brooklyn or Nothing for Pitcher Doc Scanlon,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 25, 1907: 24.

19 Brooklyn Citizen, December 9, 1907: 3.

20 “Scanlon Leaves for His Home; Will Sojourn in the South,” Brooklyn Standard Union, January 15, 1908: 4.

21 “Superbas and Reds Ready for Contest,” Brooklyn Times, March 24, 1908: 8.

22 By August, however, Scanlan was well enough to pitch a Sunday game for Gramercy, a Brooklyn semipro nine, as reported in the Brooklyn Standard Union, August 6, 1908: 6.

23 “‘Doc’ Scanlon Will Pitch for Brooklyn,” Newark Evening Star, December 9, 1908: 8.

24 “Scanlon Going South,” Brooklyn Times, February 17, 1909: 5.

25 Brooklyn Eagle, April 2, 1909: 2.

26 Brooklyn Eagle, March 12, 1911: 37.

27 “Scanlon May Be Traded,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 26, 1911: 18.

28 A term coined by Brooklyn Eagle sportswriter Thomas S. Rice during the 1911 season.

29 “Brooklyn Gets Eddie Stack in Trade for Doc Scanlon,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 15, 1911: 22; “Stack Traded for Scanlon,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 15, 1911: 12.

30 F.C. Richter, “Quaker Quips,” Sporting Life, February 3, 1912: 5. See also, “Baseball Dope of the Big Leagues,” Paterson (New Jersey) Evening News, January 26, 1912: 20. The Scanlan file at the GRC contains a letter dated February 20, 1911, in which Doc complains about Ebbets to National Commission chairman Garry Herrmann.

31 “Scanlan Makes Denial,” Brooklyn Times, July 231, 1913: 8.

32 “‘Doc’ Scanlan to Try a ‘Come-Back,’” Brooklyn Standard Union, February 27, 1914: 12. Ebbets had consummated the Scanlan-for-Stack trade by sending $1,500 to the Phillies in lieu of his recalcitrant hurler. He then placed Scanlan on Brooklyn’s ineligible list. While he remained on that list, even semipro team were leery of appearing on the same ball field as Scanlan.

33 “‘Doc’ Scanlan, Close to 300, Pitches Ball at Syracuse,” special to the Brooklyn Eagle, July 1, 1918: 20.

34 “‘Doc’ Scanlan, Close to 300.” See also, “Doc Scanlan Can Still Put Them Over,” Brooklyn Times, July 1, 1918: 8. Scanlan’s special guest receiver that afternoon was Dr. Charles W. Demong, his batterymate on the Syracuse University team of 1902.

35 See e.g., Frank Reil, “‘Doc’ Scanlan, Old-Time Dodger Pitcher Recalls Early Ebbets Days,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 4, 1934, 41; Bill McCullough, “Scanlan, Old-Timer, Ranks Mungo Best Dodger Pitcher,” Brooklyn Times, July 7, 1934: 9.

36 According to the 1940 US Census.

37 Posthumous player questionnaire for Doc Scanlan completed by his brother Frank.

Full Name

William Dennis Scanlan

Born

March 7, 1881 at Syracuse, NY (USA)

Died

May 29, 1949 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.