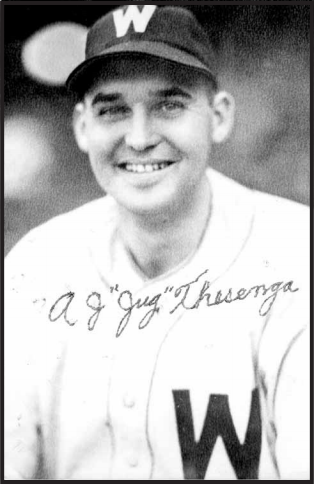

Jug Thesenga

Jug Thesenga was sick through the entire flight from Kansas to New York City. This boy from South Dakota was on his way to Yankee Stadium to start for the Washington Senators the next day. That was September 1, 1944, and the Senators were desperate for pitching during those World War II years. Scouts plucked Thesenga from the Wichita Cessna Bobcats airplane factory semipro team, which was playing in the semipro National Baseball Congress World Series at the time. Nicknamed “Jug” because of the expression at the time that curveballs resembled jug handles, Thesenga was on his way to the majors after a career that had included stops in towns like Vermillion, Sioux City, Waterloo, Tyler, Texarkana, Mount Pleasant, Enid, and Wichita.

The Senators gave Thesenga $2,500 to pitch for the remainder of the season.1 He pitched his entire major-league career for the Senators: all 12 innings that September of 1944. But his story is much larger and today it’s hard for us to imagine that Thesenga could make more money pitching at the semipro level than what the Senators were paying him. While labeled a replacement player during World War II, his greater accomplishments are verified by his inductions into both the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame and the National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame. There is even a monument dedicated to him at the NBC “Walk of Fame” in Wichita.

Arnold Joseph Thesenga was born on April 27, 1914, in Jefferson, South Dakota, although some census records list his birthdate as 1915. He was born to Diedrick or “Diddie” Thesenga, but the last name is also spelled “Theringer” in earlier records. Diedrick Thesenga is listed as a mailman in the 1900 census and as a barber in the 1930 census. Diedrick married Alice E. Ryan in 1910. Jug’s grandparents, George and Anna (Hachen), emigrated from Germany in 1883. (George Thesenga was listed as a railroad day laborer in the 1900 census.)

Arnold Thesenga graduated from the Southern State Normal School in 1934. He is mentioned in an article about the Southern football team.2 Southern became Southern State Teachers College in 1947, and then the University of South Dakota at Springfield in 1971. The school closed in 1984 and the land is now occupied by the Mike Durfee State Prison.3

Thesenga began making money from his pitching arm as early as his high-school years. He lived the life of a true itinerant ballplayer, bouncing from town to town. On one occasion he headed to Nebraska for $200 to pitch for a semipro team in Bassett against a team from Winner, South Dakota. Thesenga gave his uncle $200 to place a bet that he would win, and then walked away with $400 after his the victory.4

“I made as much pitching one game as my old man made cutting hair for a week. He didn’t understand that, but I helped support the family,” Thesenga told the Wichita Eagle in 1990.5 He did not consider baseball as a career, but as a way to make some quick cash. “I always said that if I could find a job that would pay $100 per week, I would quit.”6

Thesenga remembered seeing Babe Ruth play in 1928 or 1929. “It was an exhibition game in Sioux City, Iowa,” he said later. “I was just a kid. We all thought he was a real hero. Actually, I thought Lou Gehrig was a lot better ballplayer, but the records didn’t show it that way.”7

Thesenga was married to Josephine Johnson (born 1915 or 1916) on July 11, 1935, in Charles Mix County, South Dakota, by a Catholic priest.

The Sioux City, Iowa, Cowboys of the Class A Western League supposedly signed Thesenga in 1935. Thesenga’s daughter Delores said in a 2002 interview that his first start was against Satchel Paige.8 That would have been an exhibition game against the Bismarck, North Dakota, Churchills. Delores said her father pitched four scoreless innings but Paige got the win. This author could find no records to confirm this; however, Negro and barnstorming teams often filled in the schedule when teams went bankrupt.9 According to Thesenga, he finished that year with Connie Mack’s Athletics as a batting-practice pitcher without a contract. He went back to Sioux City, being told by Mack that “I needed more experience.”10 However, no records were found to confirm that Thesenga was in Sioux City or Philadelphia in 1935.

The records clearly show that in 1936 Thesenga did pitch for Sioux City, a club managed by future Hall of Famer Dave Bancroft. He was 5-7 with a solid 3.15 ERA in 97 innings pitched. In 1937 he was 14-12 with a 3.47 ERA in 187 innings for Sioux City, which was then a Detroit-affiliated team with several future major leaguers. The Western League itself, however, was floundering during the Depression. On July 6, 1937, the Rock Island team disbanded and the league itself folded after the season due to financial problems. The Cowboys joined the Class D Nebraska State League for 1938.

With the demise of the Western League, Thesenga was a free agent in 1938. He worked out in spring training with the Cowboys. Expectations were high; Thesenga was referred to as “a stellar hurler for the Western League club, over the prior two seasons.”11 Thesenga eventually did sign with Sioux City, and compiled a 9-7 record with a 4.36 ERA. Later in 1938 he was sent to the Waterloo Red Hawks of the Class B Three-I League (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa). In 1939 he posted a 4-6 record with a bloated 6.75 ERA in 72 innings pitched over 14 games for the Red Hawks, a Cincinnati Reds affiliate. Later in 1939 he was sent to the Durham Bulls team of the Class B Piedmont League, where he was 5-5.12

In 1940 Thesenga started with the Tyler Trojans of the Class B East Texas League, a St. Louis Browns affiliate. He was praised for having a near .500 record in three seasons despite being on “tail end clubs,” and manager Bobby Goff was said to have “had to dicker against several clubs of the higher classification to land Thesenga. …”13 Tyler won the East Texas League championship, going from worst to first during the course of the season. However, Thesenga was long gone by that time, having been released on May 11.14 Thesenga was next seen pitching for the Texarkana Liners, also of the East Texas League, which was his last minor-league stop.

Thesenga finished 1940 with the semipro Mount Pleasant (Texas) Cubs. In one outing the so-called “curveball artist” struck out 10 in a game against the Paris (Texas) Orphans.15 Oddly enough, Mount Pleasant loaned Thesenga to the Paris team for a future game “in order to make the game interesting.”16 He finished with a 15-4 record. Thesenga saved a game in the Denver Post semipro tournament and got his first win at the National Baseball Congress World Series.17 Thesenga recalled that he was the only non-native of Texas on the Mount Pleasant team and the manager had determined to only use Texas players in the national tournament. “However, we were getting beaten around pretty badly in the opener, so he decided to put me in and I shut them down.”18 This was just the beginning of Thesenga’s successful semipro career and he became a regular at the National Baseball Congress World Series, the annual double-elimination tournament held in Wichita since 1935.

The NBC World Series was the creation of Ray “Hap” Dumont and over the decades more than 700 major-leaguer have played in the tournament, including Satchel Paige, Johnny Pesky, Roger Clemens, and Barry Bonds.19 Dumont, a Wichita sporting-goods salesman, was an innovator ahead of his time. He was the first to use compressed air to clean off home plate, used machines to deliver balls to the umpires, tried glow-in-the-dark baseballs, used scoreboard timers to hold pitchers to 15 seconds between pitches, and also held early-morning games for those leaving the graveyard shift. He also hired women umpires, and even “miked up” umpires so the crowd could hear them announce lineup changes.20 That didn’t work so well, according to Bob Rives, as X-rated arguments with managers were not for the family-friendly crowd Dumont was trying to attract. Dumont also scrapped his idea of giving batters the option of running to first or third base on a batted ball.21

Dumont hatched his idea for the national semipro tournament while watching circus clowns play a Sunday baseball game against local firemen. The clowns couldn’t hold a circus on Sunday because of the Blue Laws, but they sure entertained the crowd at the game. Dumont persuaded the city to build a stadium to hold a national tournament. He then lured Satchel Paige with $1,000 to bring his integrated Bismarck team to the tournament, even though Dumont didn’t have the money upfront to pay him. Paige became the star attraction in the 1935 tournament as his North Dakota team won the NBC World Series, the crowds came, and Dumont had a legacy that continues.22 Whitey Herzog put it aptly: “I’d say a good word or more about Hap if only because he had more guts than a burglar or one of my run-sheep-run Redbird baserunners. To begin a national tournament when the country was starving, and the Midwest as dry as me after a doubleheader, took a lot more courage than you’d get out of a bottle of Budweiser.”23

Jug Thesenga is the winningest pitcher in the history of the NBC World Series. Besides Mount Pleasant, he pitched for three other teams, going 14-3 in nine different tournaments. “I just lasted longer than anybody else, I guess,” he noted humbly.24 In 1941 Thesenga pitched for the Enid (Oklahoma) Champlin Refiners. One of his wins was a one-hitter over a club from Vermont.25 Thesenga was named the best pitcher of 1941 with a 3-0 record as Enid won the tournament over the Waco Dons. The tournament winner would traditionally travel to Puerto Rico for an international tournament, but Enid declined because several players had winter wartime jobs that kept them on deferment from military service.26 Because of the war only 10 minor leagues were still in operation by 1944,27 so Thesenga was in the right place at the right time in having a steady job and a semipro baseball team to belong to. His legendary Kansas career was about to begin.

There were high expectations as Thesenga came to the Wichita Cessna Bobcats in 1942, a military-sponsored airplane factory team. Thesenga was leaving the Enid championship team with his manager Nick Urban, who had managed Enid for 10 years and guided them to three national semipro titles. Between 1942 and 1947 Thesenga pitched for (and managed in 1946-1947) the Bobcats and compiled a 9-3 record in the NBC tournament. Cessna never won the tournament, but did win the Kansas state semipro title in 1945.28

“I decided to stay in semipro ball and quit traveling so much. That’s how I ended up in Wichita, Kansas, working in the defense industry and managing a baseball team,” Thesenga said. “I was on a deferment as a tool-and-die worker,” Thesenga recalled.29 This job gave him a deferment from military service, a steady income in a defense industry job, and also a baseball team for which he would both pitch and manage. Thesenga was rocked for 10 hits in a losing effort in the NBC Kansas semipro title game in 1944 against the Fort Riley Centaurs.30 Former National League batting champion Pete Reiser, in Army service at FortRiley, went 4-for-4 against Thesenga, including the game-winning single in the bottom of the ninth. Thesenga recalled, “I can still remember looking up and seeing (Ray) Dumont chomping on his cigar and hoping we could hold off Fort Riley to force a second game.”31

In the 1944 NBC tournament, Thesenga beat the Camp Ellis, Illinois, team with a four-hit shutout.32 Life dramatically changed for Thesenga at that tournament, however. Major-league scouts were always in attendance at the NBC World Series, looking for a diamond-in-the-rough player. The war years had depleted all rosters of talent, so scouts took interest in what was happening in Wichita. Only the A’s and Yankees didn’t send scouts, yet few players were actually available. Many were already on military teams or under contract to other minor league clubs. “Only one player, the portly Arnold (Jug) Thesenga was hauled directly into the majors,” wrote Jack Copeland in The Sporting News.33 Thesenga remembered, “In 1944 I had won two games in the National Baseball Congress World Series against a good Army and Navy team. I won 15 games that year. Washington made me an offer — $2,500 to finish the season, which lasted six or seven more weeks.”34

Thesenga was scouted by Joe Cambria, the scout famous for finding talent in Cuba and signing more than 400 players.35 Cambria earlier that year had signed 15 Cuban ballplayers36 and got them six-month visas so they would be immune to draft regulations.37 Cambria not only raided Cuban talent but also the amateur leagues, which is how he found Thesenga. “In those war years you had to do a lot of cutting and pasting to make a ball club,” Ossie Bluege, Washington Senators manager, said years later.38

The Senators flew Thesenga to New York, where he made his major-league debut on September 1, 1944, at Yankee Stadium against Steve Roser. It is not hard to imagine why Thesenga was sick on the plane flight to New York, for this was the big stage for this South Dakota boy. The game was anything but a classic, however, and there was no magical Hollywood ending. Louis Effrat of the New York Times watched the sloppily played game and sniped, “Too ludicrous for words was the baseball exhibition between the Yankees and Senators at the Stadium yesterday. … Two-and-a-half hours of up-again-down-again diamond warfare in which the silliest things happened … all of which showed a ladies’ day crowd of 5,336 fans how this game of baseball should not be played.”39

Thesenga, described by Shirley Povich of the Washington Post as “the baldish, 30-year-old right-hander,” shut down the Yankees for five innings and the Senators enjoyed a 3-0 lead.40 But Thesenga’s famous curve was all over the place and he walked eight. The Yankees finally got to him in the sixth inning, scoring four runs on five hits, ending Thesenga’s debut. His final numbers were a no-decision of five innings pitched, five hits, two earned runs, eight walks, and one strikeout. Washington rallied to win the game with five runs in the eighth inning.

Interestingly, the hit that ended Thesenga’s only major-league start was by future Hall of Famer Paul Waner, then a 19-year veteran. The Brooklyn Dodgers had just released Waner days before and the Yankees had signed him at 10 o’clock that morning.41 The three-time National League batting champion (1927, 1934, and 1936) and former MVP (1927), who kept a job at age 42 because players were hard to find, wound up getting the final hit of his career, number 3,152, against Thesenga.

Thesenga faced the Yankees again on September 3, pitching 3⅓ innings and giving up three earned runs. On September 9 he pitched an inning of relief against the Phillies, giving up one earned run. He pitched a scoreless inning of mop-up relief in an 11-5 loss to the Red Sox on September 16, and then in a final performance in Cleveland surrendered one earned run in two more innings of mop-up relief. That concluded Jug Thesenga’s brief major-league career (0-0, 5.11 ERA, 12 1/3 innings pitched).

The 1944 season was disappointing for the Senators, who had been picked to win the pennant based on their turnaround season of 1943. Instead, Washington finished last with a 64-90 record in 1944. War departures and freak injuries took their toll in a lost season, all of which opened up the opportunity for Thesenga’s brief major-league career.

The Senators played a key role in deciding the American League pennant. Detroit and St. Louis were tied for first going into the last game of the season on October 1. The Senators played spoiler and knocked the Tigers out of first place, setting up the only all-St. Louis World Series, between the Browns and the Cardinals.

In 1945 Thesenga returned to his Cessna wartime job in Wichita and did not attend spring training with the Senators.42 His Cessna Bobcats career continued. He won his 13th NBC World Series game in the 1947 tournament, beating the Bellingham (Washington) Bells.43 Thesenga’s final NBC World Series win was in 1948 for the Vermillion (South Dakota) team.44 His name shows up again, pitching for the Wichita Roskam Realtors in the Kansas semipro state tournament in July 1950.45 When Thesenga retired from Cessna he began a real-estate career.

One of the five eight-foot statues at the NBC “Walk of Fame” at Lawrence-Dumont Stadium in Wichita is dedicated to Thesenga. The inscription reads, “Arnold Thesenga has more wins, 14, than any other pitcher in NBC history. Thesenga played in nine national tournaments in Wichita. The “Jug” was short for ‘jughandle,’ an archaic expression used to describe the degree of curve on a pitcher’s breaking ball.”46 Thesenga was inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982 and the NBC Hall of Fame in 1995.47

Thesenga remained in Wichita the rest of his life. Besides working for Cessna and then his real-estate career, from which he retired in 1988, Thesenga also owned a bar in downtown Wichita. He continued to passionately follow baseball, even watching separate games on two TVs in his living room. He and Josephine had four children, three of them boys, “but none of them gave a damn about baseball,” Thesenga later regretted. “I guess dragging them around the country while I was playing, they got sick of it. But I couldn’t have survived without baseball. I’d have played for nothing if I’d have had to.”48

In 1954 Thesenga was arrested along with three other men (including James F. Meikle, a McConnell Air Force Base private), on charges of burglary for operating a whiskey theft ring. Wholesale Liquor Inc. was robbed, and 36 cases of whiskey were found in Thesenga’s garage. Two of the other men carried out the actual robbery at the warehouse, where one of them worked as a substitute night watchman. They attempted to sell some of the liquor to an Air Force officer on the base, who then reported his suspicions to the sheriff. A sting operation was set up in the parking lot of a local night club, and the delivery was made by Meikle to waiting deputies. Upon interrogation of Meikle, the others, including Thesenga, were arrested. They were each released on $2,000 bail.49 No further information was found on the case.

Jug Thesenga died on December 3, 2002, and his wife, Josephine, died on November 21, 2009. Both are buried at White Chapel Memorial Gardens in Wichita, Kansas.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited, the author consulted the Baseball Hall of Fame file on Jug Thesenga, baseballreference.com, retrosheet.org, census.gov, and ancestry.com. The author also is thankful for research assistance from Robert Rives, Tom Dunkel, Carol Jennings, Andrew Wright, the National Baseball Congress, and the Berwick (Maine) Public Library.

Notes

1 Craig Allen Cleve, Hardball on the Homefront: Major League Replacement Players of World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2004), 172.

2 Daily Plainsman (Huron, South Dakota), September 14, 1933.

3 Austin Kaus, “South Dakota Small Town Colleges Gone, but Nostalgia Remains,” Prairie Business.Prairiebizmag.com/event/article/id/10071/, accessed March 21, 2014.

4 Bob Broeg, Baseball’s Barnum: Ray “Hap” Dumont, Founder of the National Baseball Congress (Wichita, Kansas: Center for Entrepreneurship, W. Frank Barton School of Business Administration, Wichita State University, 1989), 151.

5 Bob Lutz, “A Yearly Occurrence at the World Series: Thesenga Would Show Up in Town, Win a Few Games,” Wichita Eagle, July 29, 1990, 8G.

6 From the program of the 1995 National Baseball Congress World Series

7 Bob Curtright, “Replaying It With the Babe: Old-Time Ballplayers Remember When They Saw Ruth,” Wichita Eagle, April 16, 1992, 1C.

8 David Trombley, “Major Leagues’ South Dakota born players,” usfamily.net/web/trombleyd/SD%20Born.htm, accessed March 28, 2014.

9 W.C. Madden and Patrick J. Stewart, The Western League: A Baseball History 1885-1999 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2002), 195.

10 Cleve, 171.

11 Dan Desmond, “Pete Monahan Likes the Looks of His Sioux City State Loop Outfit,” Lincoln Evening Journal, May 4, 1938, 13.

12 Cortland (New York) Standard, September 16, 1939; 7.

13 Dallas Morning News, March 10, 1940.

14 Dallas Morning News, May 12, 1940.

15 Paris (Texas) News, July 19, 1940.

16 Paris (Texas) News, July 24, 1940.

17Dallas Morning News, August 10, 1940.

18 From the program of the 1995 National Baseball Congress World Series

19 Royse Parr, “Semipro Baseball’s Golden Era (1935-1941): A Tale of Two Cities,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 2006, 56.

20 “Ray Dumont Found Dead in NBC Wichita Office,” Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, July 4, 1971; 4F.

21 Cynthia Mines and Iris Davis, “Take Me Out to the Ballgame: Rich Baseball History Comes Full Circle with Vintage Team,” Wichita Times 4 no. 12 (2005), 4.

22 “History of the NBC,” nbcbaseball.com/nbchistory.html, accessed April 23, 2014; Mines and Davis, 3.

23 Broeg.

24 Lutz.

25 Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, August 18, 1941; 9.

26 Parr, 64.

27 Ibid.

28 Emporia (Kansas) Gazette, July 25, 1945.

29 Ibid.

30 Iola (Iowa) Register, July 27, 1944, 8.

31 From the program of the 1995 National Baseball Congress World Series

32 Sgt. Mickey McConnell, “Super hurling gives semi-pro meet fine show,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1944, 13.

33 Jack Copeland, “Prospects Sparkle at Wichita, but Scouts’ Pens Are Shackled,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1944, 13.

34 Cleve, 172.

35 Brian McKenna, “Joe Cambria,” The Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/4e7d25a0, accessed March 30, 2014.

36 “Fifteen More Cubans for Senators,” New York Times, March 18, 1944.

37 “Immunity to Draft for Latin Americans,” New York Times, April 16, 1944.

38 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout: Fifteen Managers Speak Their Minds (Chicago: Follett, 1977), 157.

39 Louis Effrat, “Senators’ 5 in 8th stop Yankees, 10-7,” New York Times, September 2, 1944, 15.

40 Shirley Povich, “Griffs Score Five Times in Big Round,” Washington Post, September 2, 1944, 6.

41 Ibid.

42 Washington Post, March 15, 1945, 12.

43 Winona (Minnesota) Republican Herald, August 26, 1947, 12.

44 Parr, 64.

45 Hutchinson (Kansas) News, July 9, 1950, 10.

46 Ibid.

47 “National Baseball Congress Hall of Fame,” . nbcbaseball.com/nbchof.html; “Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame Inductees Bios,” . wichitahof.com/Baseball_Inductees_Bios.htm.

48 Lutz, 8G.

49 “Ex-Washington hurler arraigned,” Salina (Kansas) Journal, July 25, 1954, 16.

Full Name

Arnold Joseph Thesenga

Born

April 27, 1914 at Jefferson, SD (USA)

Died

December 3, 2002 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.