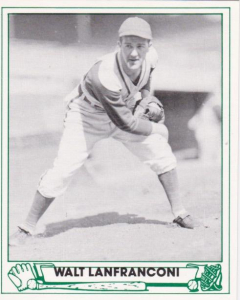

Walt Lanfranconi

Born in Barre, Vermont, of an immigrant father who worked in the granite industry. Died in Barre, Vermont, 70 years later. Hearing those bare facts, you might think Walt Lanfranconi’s story is that of the quintessential Vermonter, living his life out in obscurity in the town where he was born and raised.

Born in Barre, Vermont, of an immigrant father who worked in the granite industry. Died in Barre, Vermont, 70 years later. Hearing those bare facts, you might think Walt Lanfranconi’s story is that of the quintessential Vermonter, living his life out in obscurity in the town where he was born and raised.

Walt Lanfranconi answers to the foregoing description — but between his birth and death he spent time in Switzerland, England, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, Germany, Canada, Cuba and Argentina. And his long career in baseball, which included a quick season-ending stint with the 1941 Chicago Cubs and one full season with the Boston Braves in 1947, took him all over the United States, as well. The kid from Barre saw a lot of the world, and in the end decided there was no better place to settle down than Vermont.

Walter Oswald Lanfranconi was born in Barre on November 9, 1916. His father, Stefano, had been a stone cutter in Switzerland, not far from the town in northern Italy where Battista Polli (father of Lou Polli) had engaged in the same trade. Like the Pollis, Stefano and Gina Lanfranconi emigrated to Vermont so that Stephen could find work in Barre’s granite industry.

After five years of cutting stone in the Green Mountains, Stefano moved his family back to the Swiss Alps when Walter was 18 months old. Why he returned to Switzerland is not entirely clear — by some accounts he was homesick, but by others he inherited property on the Swiss-Italian border. Whatever the case, Stefano came back to Barre after two years in Switzerland. Walt, meanwhile, remained in the Alps with his mother, attending kindergarten and primary schools there. It was not until the future big leaguer was six that he and his mother returned to Vermont.

In the baseball hotbed that was Barre in the 1920s and ’30s, Walt took to America’s national pastime at the relatively late age of 13. He was small for an athlete (he grew to be only 5’7″ and 155 lbs.), but at Spaulding High School he became known as the “Boy Wonder” of the Granite River Valley, lettering in baseball, basketball and track.

While at Spaulding Walt’s pitching abilities caught the attention of Stuffy McInnis, the old Athletics and Red Sox first baseman then scouting for the Washington Senators. Walt received a letter from Clark Griffith, owner of the Senators, instructing him to report to Fenway Park the next time the Senators came to Boston. As the story goes, Washington manager Bucky Harris took a quick look at the diminutive Vermonter and sent him home, saying, “I don’t want any drugstore pitchers.”

After three years at Spaulding High School, Walt attended Montpelier Seminary for his senior year of 1937. Before the school year was over he caught on with the Burlington Cardinals of Vermont’s famous Northern League, where his teammates included future major leaguers Frank Hoerst and Lennie Merullo. Walt’s manager at Burlington was Ray Fisher, another Green Mountain Boy of Summer, but Fisher released him after only three games.

Walt got even. Pitching for the rival Montpelier Senators on the day he graduated from high school, Walt hurled a one-hit masterpiece against Fisher’s crew before a packed crowd that included several big-league scouts. One of them, former major leaguer and UVM athletic director Clyde Engle, signed Walt to a contract with the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Single-A International league.

Walt appeared in one game for Toronto in 1937, allowing ten runs in only four innings. Obviously he was not yet ready to pitch at the highest level in the minor leagues. He was sent to Smith Falls, Ontario, of the Canadian-American League where he more than held his own. He was 3-3 with a 3.00 ERA, striking out 41 batters and walking just ten in 51 innings.

In 1938 Walt was called back to Toronto where he toiled for the next four seasons. During spring training 1939 he enjoyed his greatest baseball thrill to that point, pitching in an exhibition contest against the Boston Red Sox. In the game’s early innings Boston’s heavy artillery bludgeoned the Toronto pitching staff, and soon it was Walt’s turn to face a star-studded lineup featuring Hall-of-Famers Jimmie Foxx, Joe Cronin, Bobby Doerr and a rookie named Ted Williams. Walt mowed them down for several innings, giving up just two singles, both to Doerr.

Walt’s third season in Toronto, 1940, proved to be the shortest of his professional career. In his fourth appearance he suffered a chipped elbow and could not throw without severe pain. The Maple Leafs sent him to Dr. George Bennett of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. The diagnosis: bone chips had grown onto the nerves in his elbow, and even with surgery his chances were 1-in-100 of ever pitching again. “I can’t pitch as it is,” Walt told Dr. Bennett, “so what have I got to lose?” The surgery was performed on June 3 and Walt was placed on the voluntarily retired list.

Overcoming the odds, Walt returned to the Maple Leafs in 1941 and was even named opening day starter by manager Tony Lazzeri, the former Yankee great. His selection irked teammate Vallie “Chief” Eaves, a Native American from Oklahoma who felt that he was the best pitcher on the Toronto staff. When Lazzeri announced that Walt would open the season, Eaves became incensed, picked up a pair of scissors and started towards Walt, saying, “It’s all your fault. I’m going to pitch today.” After Walt fended him off, Eaves went after Lazzeri and made various threats before the Toronto players chased him out of the clubhouse.

Walt won his first five starts in 1941: the first two were 5-0 shutouts, the third was a 3-1 win, the fourth another 5-0 shutout and the fifth a 2-1 decision in Jersey City before a crowd of 63,711, one of the largest in minor league history. Despite his auspicious start, Walt suddenly found himself relegated to the bullpen when Lazzeri was replaced as manager by Lena Blackburne. Best remembered as the man who discovered and marketed mud from the Delaware River to rub the gloss off new baseballs, Blackburne was known to be a bit eccentric. While managing the Chicago White Sox in 1929, for example, he engaged in a savage fistfight with one of his players, Art Shires.

The season turned upside down for Walt after Blackburne’s arrival. He lost 15 of his last 18 decisions and, not surprisingly, strongly disliked his new manager. Once Blackburne had Walt warm up in the bullpen for 15 minutes, then waved him in to pitch (or so Walt thought). Arriving at the mound, Blackburne told Walt to replace Lenny Merullo at shortstop!

On another occasion Blackburne called on Walt before he had a chance to throw a single warmup pitch in the bullpen. Entering the game with the bases loaded and no outs, he struck out the first batter and made the next two pop to the shortstop to end the game. When Walt got to the clubhouse, Blackburne told him, “That’s the luckiest relief pitching I’ve ever seen.”

At the end of the International League season Blackburne announced that he was returning to the Philadelphia Athletics as a coach the following season. Curiously, he asked Walt if he wanted to join him on the Athletics or be sold to the Chicago Cubs. Without hesitation Walt chose the latter, and he arrived in Chicago during the waning days of the 1941 season as the Cubs were sputtering to a sixth-place finish.

In his major league debut on September 12, 1941, Walt Lanfranconi started against the Cincinnati Reds. He suffered a 2-0 loss to Cincinnati ace Bucky Walters, but his fortunes that day may have been doomed from the start — Cubs manager Jimmie Wilson fielded an experimental lineup consisting entirely of rookies. Walt appeared in one more game with the Cubs that fall, pitching a single inning of relief.

The following year the Cubs held spring training at Catalina Island off the coast of California, but Walt wasn’t there long before he was sent down to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. His manager in Milwaukee was Charlie Grimm, the popular player-manager of the Cubs back in the ’20s and ’30s. Pitching both as a starter and in relief, the Vermonter became Grimm’s workhorse in 1942, finishing with a 15-13 record in a career-high 42 appearances. That season Walt even managed to save the second game of a doubleheader after pitching the Brewers to victory in the first game. With a strong season behind him, Walt looked forward to rejoining the Chicago Cubs in 1943. But with World War II raging in Europe, fate had something else in store for him.

Walt Lanfranconi spent the next three years on the front lines of the European Theater of Operations, earning two battle stars with the 12th Armored Division. Even after VE day on May 7, 1945, Walt stayed on with the occupation forces. Playing baseball for his company team, he broke his leg sliding into second base on July 28, 1945. That injury put an abrupt end to his European playing activities, although he continued to manage the company team.

After 45 months in military service, Walt arrived home in Barre in February 1946, just in time to attend training camp with the Milwaukee Brewers at Mineral Wells, Texas. Even though his leg still bothered him, Walt picked up where he left off nearly four years earlier by winning five of his first six decisions.

Then came a bad break that nearly ended Walt’s baseball career. While fielding grounders at third base during batting practice, he was hit by a line drive that cracked his right shin bone. After only a couple weeks of recuperation, Walt tried to return too soon and struggled the rest of the season, finishing with an 8-10 record. Now hampered by two leg injuries, Walt left for Barre at the end of the season thinking he was through with baseball.

When he arrived in Vermont he told his fiancee, Eda Dindo, about his decision, but she insisted that he give baseball another chance. Still Walt wasn’t convinced. It meant little to him when he learned that winter that Milwaukee had sold his contract to the Boston Braves, but Eda urged him to try at least one more season with a new ball club. Finally he agreed.

In mid-February 1947, six weeks after their wedding, Walt and his new bride took the Braves spring training train from Boston to Fort Lauderdale. The only other player on the train was a second-year pitcher named Warren Spahn, who at that point had just eight major league wins under his belt. Spahn, of course, went on to 355 additional victories to become the winningest southpaw in history. Walt and Warren became close friends and ended up rooming together on road trips.

Once in camp at Fort Lauderdale, Walt made an immediate impression by socking a batting practice home run against Big Mort Cooper. Veteran catcher Don Padgett, who caught Walt in his first spring outing against the Brooklyn Dodgers, declared that “it’s been a long time since [I’ve] seen a rookie with so much stuff this early. His fast ball took off and made a few of these Dodgers look foolish.” In the Boston Herald American, Gordon Campbell wrote that manager Billy Southworth “liked his work so far,” and Cooper was quoted as saying, “He’s got something. He has a lot of poise and I think he will help us.”

After Walt faced the St. Louis Browns in his second spring training stint, John Drohan of the Herald American wrote that “[although he was] a little wild at the start they couldn’t do a thing with his fast ball. What balls they hit were his curves, which Walt is now trying to sharpen.”

Following his third outing, word of his outstanding performance reached the Barre Times:

Boston sports writers were loud in their praise of the pitching performance given by Walter Lanfranconi of Barre in the [three] hitless innings he pitched against the Philadelphia Athletics on Monday.

Most of the city newspaper sports pages carried mention of great future prospects for the popular local big leaguer. Gene Mack, cartoonist and writer for the Boston Globe, featured a caricature history of Lanfranconi’s progress in baseball from his start upward with Toronto to his present hopes with the Boston Braves.

When asked about Walt’s chances of making the team, Southworth said, “I’ve had [pitching coaches] Johnny Cooney and Ernie White working with Walter on a change of pace that should just about enable him to do it.” Sure enough, when spring training broke up in early April, Walt was with the Braves as they barnstormed their way north. Any doubt that he would make the team was soon erased after his memorable debut in Boston.

Prior to leaving the Massachusetts capital for Milwaukee in 1953, the Braves played an annual three-game series against the Red Sox just prior to the opening of the regular season. The winner of this popular and usually well-attended series wound up with bragging rights, no matter which team did better during the regular season. And it was in the 1947 intercity series that Walt Lanfranconi became a household name in Boston.

On a cold, raw Sunday afternoon, the Sox and Braves battled for four hours to a 7-7 tie in 16 innings before some 30,884 “too thrilled to be cold” customers at Fenway Park. The game featured titanic homeruns by Ted Williams and Rudy York off future Hall-of-Famer Spahn, a rash of hits by $100,000 rookie Earl Torgeson, an unscheduled dog chasing in the seventh inning and a miraculous performance by a rookie pitcher. Relieving Spahn in the seventh, Lanfranconi held the Sox scoreless over the next six innings even though they loaded the bases with nobody out in both the 11th and 12th innings!

Comments about Walt’s heroics appeared in newspapers for the next week. In the Boston Globe, Bob Holbrook reported:

Walter Lanfranconi, who was in more hot water than a fish in Warm Springs, went in and pitched amazing baseball, retiring the Red Sox two innings in a row when the bases were choked and no one was out. He agreed that this was as harrowing an experience as he ever hopes to encounter. When he returned to the bench after retiring the Sox the entire team rose and greeted him with encouragement and praise. Lanfranconi [has] clinched a position with the Braves.

Arthur Sampson of the Boston Herald devoted a feature article to the fact that the late Dan Howley, talent scout for the Red Sox, first spotted Lanfranconi ten years earlier and was impressed with his work even then. Howley’s comments were as follows:

He doesn’t look like a pitcher in that he isn’t one of those tall, loose guys who almost stretch to the plate before they release the ball.

As a matter of fact, he’s short and a little jerky delivering the pill. He’s got a pretty good curve, however, and a sneaky fast ball. And what impresses me most is that he’s got a heart. He can get the ball where he wants to in a pinch.

He’s the sort of pitcher who makes the batter hit the pitch he wants him to hit. And such a pitcher is one who can constantly pitch himself out of trouble.

Sampson went on to comment that Howley’s words had particular application on Sunday: “[T]here was no denying that the guy on the rubber possessed all the competitive spark a pitcher needs in a crisis.”

The Braves opened the regular season at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on April 15, 1947, before a crowd of 25,623. On that historic day, dressed in a Dodger blue-and-white uniform with number 42 on the back, a Georgia-born black man named Jackie Robinson made his major league debut. Playing first base, a position he was not accustomed to, Robinson was 0-for-4 but the Dodgers triumphed, 5-3, primarily through the hitting of center fielder “Pistol Pete” Reiser and the erratic defensive play of the Braves’ Torgeson. Walt made his 1947 debut, coming in to pitch one inning of scoreless relief, allowing no hits and fanning two. He missed pitching to Robinson by one inning.

The season progressed with Walt pitching both long and short relief. Four times he was thrust into a starting role, and on the second of those occasions he was particularly successful. In the midst of a three-game losing streak, the Braves needed a starter for the second game of a July 4th doubleheader at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. After Johnny Sain, stalwart of the Boston mound corps, won the first game, 10-3, Walt came back to pitch a brilliant four-hitter in the nightcap, winning 7-1. It was his only complete game in the major leagues. According to Mike Gillooly of the Boston Evening American, Walt “had his own fielding to thank for stopping the damaging Phillies. On three occasions, he broke the backs of the Phils with lightning grabs of their smashes in a nifty exhibition of the correct way to win your own ball games.”

Some major leaguers hit the ball so hard it is nearly impossible to field. Walt learned that lesson one afternoon against the St. Louis Cardinals. His first time facing the dangerous Stan Musial, winner of seven NL batting crowns, Walt struck him out on one of his newly-developed changeups. Musial headed back to the Cards dugout, bat in hand, yelling, “You better not throw that pitch to me again.” Soon Stan The Man returned to the plate to face Walt a second time. After fooling Musial the first time, Walt thought another changeup was in order. Not fooled this time, Musial drilled it right between Walt’s legs and into center field. After rounding first base, Musial cupped his hands and yelled to Walt, “You’re lucky your center fielder didn’t have to field three balls.”

At 7:00 a.m. on Sunday, September 7, 1947, a roundtrip excursion train, “complete with diner and air-conditioned coaches,” pulled out of Depot Square in Barre. With 200 local baseball fans aboard, the train made its way on the Central Vermont and Boston & Maine railroads to Boston’s North Station. It was “Walt Lanfranconi Day,” and the 200 fans headed to Braves Field in time for pre-game ceremonies, joining another 300 who had driven from Barre.

Larry Gardner and Vermont Governor Ernest Gibson were on hand to present Walt with a brand-new, cherry red Oldsmobile convertible purchased for the occasion by hometown contributions. The Braves’ opponent that day was the Phillies, whose shortstop, Vermont native Ralph Lapointe, also participated in the pregame festivities. After the presentation, all of the Braves relievers climbed aboard and Walt circled the field while the famous Braves troubadours played the popular ditty “In My Merry Oldsmobile.”

The game that followed was anti-climactic. The Phillies shutout the Braves 2-0 as Blix Donnelly tossed a three-hitter. Walt did not pitch. It was an outstanding day nonetheless, and Walt sent the following letter to the Barre Times:

To you my friends of Barre and surrounding communities who, on September 7 at Braves Field, held a day in my honor, I wish to express my deepest appreciation.

This honor to me was more than can be expressed, for such occasions as these are held once only in a lifetime. To see such a large delegation present on “my” day was in itself a great honor indeed. Never had I imagined that such a day would ever be held for me.

I can indeed say this was without a doubt one of the finest events of my life, and one that will never be forgotten. To the person, or persons, whose idea it was to have this occasion, I wish to express my deepest thanks. Words of appreciation cannot be written. They would only be a small part of expressing the feelings which I have had since that day.

Last but not least, to each and every individual who made it possible for this day to be such a success, to all of you my friends, I can only say that this was one of the happiest days of my life.

Less than a month later the Braves ended their 1947 season. With a record of 86-68, Boston finished in third place, eight games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers and three behind second-place St. Louis. It was the Braves’ second consecutive first-division finish, the first time they had accomplished that feat since 1934. Clearly better times were just around the corner. As for Walt’s personal statistics, he saw action in 36 games and pitched 64 innings. His record was 4-4 and he recorded one save. His 2.95 ERA was the lowest to that point of his professional career.

The day after the season ended, Walt and Eda Lanfranconi drove home to Barre in their new convertible. Due to circumstances they could not have foreseen, that car would make 18 cross-country trips over the next few years.

Though he knew he was hardly the league’s best pitcher, Walt figured he performed well enough to deserve a raise in pay for the 1948 season. The Braves owners, Perini, Rugo and Maney (the “Three Steam Shovels” of heavy-construction fame), put forth several offers, each calling for more than the minimum salary of $5,000. Walt refused each offer. The owners responded by selling him and disgruntled shortstop Dick Culler to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.

The Boston media was unsympathetic to Walt’s plight. One scribe wrote:

Walt Lanfranconi figured that being a big leaguer called for a bank president’s pay…. That’s been the trouble with the Lanfranconis of the major leagues in this inflationary period. None of them looked at the other side of the picture: the six weeks away from snow and ice and cold at the close of winter; the three-hour working day; the travel about the country; the six-month working stint; or the hike in their speaking fees — sums for appearing at civic and sports events as “orators.”

That’s the reason Walt was sent down to the Pacific Coast League. That’s the reason Dick Culler, always a holdout, departed from Boston’s pleasant atmosphere. They placed too high a value on their services.

The tirade concluded with a comparison to another player with Vermont ties: “It could be that Lanfranconi will be back in a year or so — just as Tony Lupien earned another try at the big top after two great seasons on the coast. But we’ll bet when he does come back he’ll weigh the money question much more carefully.”

Alas, Walt never did return to the major leagues. While the Braves were winning a pennant in 1948, Walt spent the season as a reliever in the PCL. After a 2-5 start in 1949, Los Angeles released Walt in midseason and he joined the Dallas Eagles of the Texas League, resurrecting his career by posting a combined 38-27 record as a starter over the next two-and-one-half season. He ended his career by splitting the 1952 season with Birmingham of the Southern League and Beaumont of the Texas League.

Returning to Barre for good in 1952, Walt bought an Esso filling station on Washington Street and ran it until his retirement in 1978. Eda worked part-time in Dario Giannoni’s Jewelry Store and at Homer Fitts Company, a furniture store. The Lanfranconis raised two children, Stephen, born in 1948, and Carol Ann, born in 1954. Walt’s interests were typical Vermont: hunting, fishing and golf. He was a member of the Barre Country Club, the Mutuo Soccorso, the American Legion and St. Monica Church.

Walt was 70 when he died of a heart attack on August 18, 1986, seven years after his wife predeceased him.

Sources

A version of this biography originally appeared in Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993, edited by Tom Simon (New England Press, 2000).

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers.

Full Name

Walter Oswald Lanfranconi

Born

November 9, 1916 at Barre, VT (USA)

Died

August 17, 1986 at Barre, VT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.