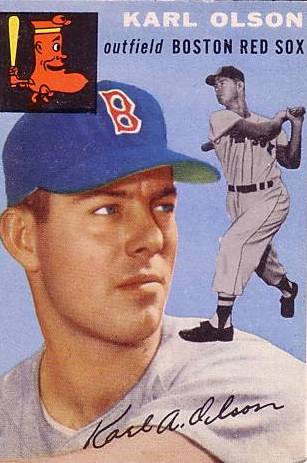

Karl Olson

Karl Olson was an outfielder who began to show a great deal of promise coming up through the ranks in the Red Sox farm system, until a stint in the military during the Korean War years seemed to derail his career. He nonetheless played parts of six seasons in the majors, largely in a backup role, but never caught fire the way many thought he might.

Karl Olson was an outfielder who began to show a great deal of promise coming up through the ranks in the Red Sox farm system, until a stint in the military during the Korean War years seemed to derail his career. He nonetheless played parts of six seasons in the majors, largely in a backup role, but never caught fire the way many thought he might.

Olson was a powerful right-handed hitter standing 6 feet 3½ inches tall and weighing 202 pounds. Many record books show him born in Kentfield, California, but he was actually born in the hospital in nearby Ross, he explained in an April 2007 interview. The family lived in Fairfax in Marin County, just north of San Francisco, and that is where he was raised. Both Karl’s parents were born in Sweden, coming to the United States in their late teens and meeting for the first time in America. Karl Arthur Olson was an only child, born on July 6, 1930. His parents were older at the time; Karl’s mother, Elsa, was 44 years old at the time of his birth.

His father was Karl Uno Olson, a carpenter by trade, who brought in about $50 a week. For about 10 years beginning when Karl was five years old, his father spent summers fishing commercially in Alaska. It was about a three-month journey – most of June to prepare the boat and travel north to Alaska, a month of fishing, and then a month bringing the boat back and getting it ready for the winter. He’d bring in between $3,000 and $6,000 for his labors, Karl recalled.

Elsa Olson had worked as a secretary in San Francisco before getting married. During Karl’s childhood, she was a homemaker. “She sure was,” Karl remembered. “Very much so. That was all she lived for, is practically my dad and I. Very much a homemaker. She had her days: Monday was wash day with the old washing machine and hanging the clothes off the line. Tuesday was shopping for the week. They had a time for everything. My dad’s sister lived next door to us, about four lots away. We were very close to her. She lost her husband early. She had two sons who were quite a bit older than I was. They were like my heroes.”

Olson’s first memories of baseball, though, come from his father hitting him fly balls in one of his aunt’s empty lots that separated the two houses. Even though his father was gone for the bulk of the summer months, “We still had the spring and the fall. I started out at an early age. He never did say how he learned about baseball, but he knew that I was always interested, even from grammar school. We would play baseball every afternoon on our dirt field at our grammar school that I went to. We had choose-up teams and everything. He knew I was very interested in that. From grammar school through high school, I didn’t care who pitched to me.”

“They never saw me play major league or high school. Not even high school.” Why was that? “That’s a good question. Another good question is the 17 years I spent at home, my dad never took my mom out to dinner once.” His father would hit balls to Karl and got him interested in baseball, and he never lacked for gloves or bats, but neither parent ever went to see a game, not even his first year in pro ball in nearby San Jose. “And high school was only a half-hour or so, but Dad’s big thing was hunting and fishing. I was raised on San Pablo Bay there, the inner bay out of San Francisco. We had a place there where we kept our boat. When duck season started, we never missed a weekend. Every Saturday and Sunday. I just loved it. I didn’t go as much for the fishing as I did for the duck hunting and I went with Dad because we were buddies. And Mom, I don’t know how she put up with it.”

Olson played in junior high, in American Legion ball, and at Tamalpais High School. He started playing varsity ball as a sophomore and credited his coach, Pop Wendering, for truly teaching him the game. “Up until pro ball,” he explained, “I was a third baseman or shortstop.” One of the other students at Tamalpais High was Joe DeMaestri, who played 11 years in the majors. Joe was two years ahead of Karl in school; DeMaestri’s father, Syl, was a bird-dog scout working with Charlie Wallgren, who lived in San Francisco and covered the area for the Boston Red Sox. Wallgren later signed Jim McDonald, Wally Westlake, Pumpsie Green, Jim Fregosi, and a number of other future major leaguers, working primarily for the Red Sox and, later, the Baltimore Orioles. Syl DeMaestri coached the Legion team that boasted both his son Joe and Karl Olson. Joe played shortstop and Karl played third base, and the two played together for a number of years. When Joe completed high school, Karl moved over to shortstop. Olson was a fast runner, and specialized in the 220-yard dash in high school. He was good at the broad jump and basketball, too.

Wallgren signed Joe DeMaestri for the Red Sox, and it was pretty much a foregone conclusion that he would sign Olson, too. Wallgren built an unusually close relationship with the DeMaestris and the Olsons. “He was very taken in with our family and everything,” Olson recalled. “The same with Joe and his family. He got to know us. He was a great guy. We visited him and his wife a lot in San Francisco, so we got to be very close. I was scouted by the Yankees and the Phillies but I never had the relationship with those scouts that we did with Wallgren.” It’s one thing for a scout to want to befriend the family of a prospect, but this was a real friendship resulting in both families traveling into the city to visit with Wallgren. “I think word got around that we were almost like family,” Karl recalled. “The same with the DeMaestris. The minute I knew that I was going to be a ballplayer, or wanted to be a ballplayer, the only team I had an interest in was the Red Sox. I didn’t even think about signing with somebody else.”

DeMaestri signed in 1946 (The Chicago White Sox drafted him out of the Red Sox farm system in 1950.). Olson graduated from high school in June 1948 and, while still 17 years old, signed a Triple-A contract with the Red Sox affiliate in Louisville. He was sent to San Jose in the California League in time to get into 70 games that year. It was Class C baseball, but – Karl said – good competition. He hit .297 in 276 at-bats, with two homers and 38 RBIs. He played outfield at San Jose and for his entire remaining baseball career. What brought about the change? “The Red Sox.” The parent club had a greater need in the outfield and a sense that it would be his best position. During the offseasons, he worked with his father at carpentry.

In the spring of 1949, Olson went to Florida to train with Louisville and was assigned to play in the Double-A Southern Association with Birmingham. “It was a little over my head,” he admitted. In 77 games, he hit six home runs and had 33 RBIs, but it was his batting average that suffered (.246). He was sent to Single-A Scranton and “I had a tough time there. Of course, it was a different atmosphere altogether. I went home after the season and I was pretty down on myself because I feel I should have done a lot better.” His average was a bit better with Scranton (.259) but he hit just one homer and drove in 35 runs. “I bounced back the next year. I got sent to Birmingham and that’s where I had one of my better years.”

That he did. In 1950, just 20 years old, in his second year with the Birmingham Barons, he suddenly broke out, batting .321 with 23 homers, 14 triples, and an even 100 RBIs. He played a full season, 545 at-bats in 147 games – career high points in all categories, as it turned out. Why had he improved so dramatically from one year to the next? The manager was the same both years – Pinky Higgins. “I don’t know what it was. Just everything fell into place. I didn’t care who pitched. I did have a tough time up until about the All-Star Game and then after that I really went good.” He was fortunate to escape serious injury late in mid-September; he had to leave the game on the 15th after he leaped to catch a ball up against the outfield fence and the ball caromed off the wall to “hit him square on the forehead.”1 His shoulder and leg were hurt, too, but X-rays proved negative.

Likely, he simply matured and came into his own. Olson had another explanation: “Maybe it’s because I met my present wife that winter.” He married Patricia Malty and they have remained happily married for more than 50 years. “She went to Marin Junior College there in Kentfield and then when I came home from the season after Scranton one of my real good buddies — he was going to Marin Junior College — he called up and (told) me that there was a couple of girls that were going to a dance and they were looking for a blind date. He said, ‘Do you want to go?’ and I said, ‘Sure.’ He picked me up as we went to the rooming house where they lived and I was fortunate that my present wife got in the back seat and because my buddy was driving, I got in the back seat and that was a blind date on Halloween night. That worked out wonderful. We had two summers where we were apart for three months but it still worked out.” The friend who introduced them was Karl’s best man at the wedding and still lives just a couple of miles away from the Olsons in the Lake Tahoe, Nevada, region where they reside. They are frequent golf companions.

After the 1950 season, Olson’s three-year deal with Louisville was up, and it was time to re-sign, though the Korean War was under way and there was concern that a number of players his age might get taken. Olson was offered another contract, but at a lower salary – despite the excellent year he’d had in Birmingham. “And I was a little upset with that, so I didn’t report. I stayed home. We finally got together. I don’t remember when it was but the season had started at Louisville. So I got back there — no spring training, no nothing. In those days, you know, we went to spring training to get in shape. Now the guys are in shape. But it worked out, and I got going.”

Pinky Higgins had become manager in Louisville, so Olson worked under him for the third year in succession in 1951. This was Triple-A now, but after the first 63 games, he was hitting a virtually identical .320 and he’d accumulated 31 RBIs. For the second year in a row, he’d beaten out Jimmy Piersall for an outfield position. Then the Red Sox beckoned. “Charlie Maxwell, Leo Kiely, myself, we got called up in July to go to the Red Sox. I was there somewhere around a month. Just long enough to get pension time in. Then I got my induction into the Army and had to go home.”

His first game in a Red Sox uniform was an exhibition game against the New York Giants at Fenway Park, and Olson hit an opposite-field home run into the bullpen in right field. He appeared in five games for Boston, debuting on the last day of June, 1951. Olson accumulated 10 at-bats, with one hit — a single — and of course he remembers it well. “Yeah, it was against the Yankees in Yankee Stadium. Actually what it was, I got the bunt sign and I bunted the ball past the pitcher [Bob Kuzava]. To Jerry Coleman. That was my first hit. The next game was against Lopat and of course he got me out four times. That was it.” Olson’s bunt advanced Billy Goodman to third base, and he scored a moment later on Buddy Rosar’s sacrifice fly. Olson was 1-for-4 in his first game, playing right field. The next day, he was 0-for-3 against Lopat. With Ted Williams in left, Dom DiMaggio in center, and Clyde Vollmer in right, and the Red Sox taking first place right after the All-Star break, Olson never got much playing time.

He came in as a late-inning defensive replacement for Ted Williams in the second game of a doubleheader on July 15, a game the Red Sox had pretty much in hand, and he filled in for Ted a week later when Williams was removed for a pinch-runner. This all occurred while Vollmer was in the midst of a nearly unprecedented hot streak. Then Olson got his induction notice and left.

Actually, Olson left a little before receiving the notice. His mother let him know it was coming, and he packed up and left for home. “I went home flying west and my induction notice was going east, so we passed. That didn’t set too well with Mr. [Red Sox general manager Joe] Cronin. He thought I should stay until my induction notice got there. The problem was he got rid of Dropo for me and that didn’t set well because he used up an option there and then he had to get Dropo back to take my place. We got home and we had about 10 days so we decided to get married and — 10 days later — I was in the service after a four-day honeymoon.” (Walt Dropo had been Rookie of the Year in 1950, but on June 25, 1951, he had been optioned to San Diego when Olson was called up.)

Olson served in the 78th Infantry, stationed at Ford Ord (Salinas, California), for 11 or 12 months. Like many ballplayers, he was placed on a service team, and his club included Del Crandall, Jim McDonald, and a few others. He appeared in 90 games for Fort Ord, but when the team advanced to an all-tournament playoff in Wichita (Olson hit .420 for Fort Ord), he sprained his ankle and was unable to take part. With about 11 months remaining in his tour of duty, he was sent over to Japan as staging for Korea. His coach at Ford Ord, though, had paved the way for him, sending papers ahead of him. “I was all lined up with the pack and the M-1 and everything to take off but they called me out and I went to Camp Drake then and spent nine months as a mailman there.” Olson sorted mail for the troops coming to and going from Korea; Camp Drake was a base fairly close to Tokyo. He played a lot of baseball there – he said he played in 70 games. He never saw combat in Korea, and he was sent home about a month before his time was up. Red Sox teammate Leo Kiely saw service time, too, and played on the same team in Japan as Olson.

There was quite a reception for Olson the day he returned to the Red Sox shortly after the 1953 All-Star break. After missing almost exactly two years; he and Patricia drove back across country to report for duty at Fenway Park. “It took us a week to get there or so, but the day I walked in was the day that Ted Williams walked in. We came into the clubhouse the same day.” On July 30, both Williams and Olson took batting practice at Fenway.

Olson had played ball during his two years in the army; Williams had not played once during his stretch of combat in Marine aviation. Karl was ready sooner, and played his first game on August 4, doubling to center field at Fenway, driving in the tying run in the game – playing left field in place of Capt. Williams. Asked if he felt glad to be back, Olson answered, “Does it feel good to have someone slip you a million bucks? Baseball is living, brother. I feel like I’m back home again.” He added, “There were times that I thought I’d never get back. Two years seemed like a long, long time.”2 Olson said he considered himself the luckiest guy in the Army because of how often he played baseball and, consequently, never got out of shape. At the time he was taken into the Army, Olson had been, Hy Hurwitz wrote in The Sporting News, “the hottest outfield prospect in the Red Sox organization. Yes, even more highly regarded than Jim Piersall.”

He would never fulfill that promise, and had a hard time playing major-league ball after two years of less competitive play. He was not really in the best condition, some 15 to 20 pounds over optimal playing weight. On August 23, though, he had a big hit in Washington – a ninth-inning double that won the game for the Red Sox. Ted Williams had left the game. Olson was hitting .050 at the time, but drove a double and drove in Jimmy Piersall with the go-ahead run against Washington. Just six days later, he featured in a game in another way. He hit into a triple play.

It was August 29, at Comiskey Park, and the White Sox led 5-1 in the top of the ninth. Boston had the bases loaded and nobody out, with Olson at the plate. Starter Connie Johnson threw two straight balls to Olson, and Virgil Trucks was summoned from the bullpen. He got a called strike, and then Olson hit a ball to Ferris Fain at first. He caught the sinking liner, stepped on the bag, and threw to second for the third out. Game over.

Several days later, Olson hit his first major-league home run (one of only six hit by the erstwhile slugger), off Steve Gromek in Detroit, a two-run homer in the seventh that provided the first two Red Sox runs in a 5-4 loss. Olson’s average in the 57 at-bats he put together after returning from the service was a disappointing .123. “Yeah, but I hit the ball pretty good,” he remembered. “It was one of those things where, you know, you’re in a slump but you hit the ball pretty good.”

And the Red Sox were cautiously content to have him back in 1954. He was what was termed a “roster-free participant” because of his time in the service. “If there was like 25 on the roster, I was 26.” The Red Sox hired Glenn Wright as a special hitting coach to work with Olson during spring training.

Ted Williams broke his collarbone on the first day of spring camp in 1954 and so Karl saw a lot of playing time early on, though Hy Hurwitz wrote in the March 24 issue of The Sporting News that Olson “hasn’t been living up to promises.” By the time the spring season was over, though, Olson was hitting .300 and had worked in all three outfield positions. Olson acknowledged that he had lost his batting eye a bit in Japan, because he wasn’t facing first-rate pitching.

During the season, he got into 101 games, hitting .260 in 227 times at bat with 20 RBIs; manager Lou Boudreau had Billy Goodman share some left-field playing time with Olson. The Red Sox had acquired Jackie Jensen during the offseason, and he became a fixture in the outfield. Olson played often in a backup role, but he hit just one home run, an August 19 three-run homer off Camilo Pascual in Washington. The day before, he had the game-winning hit in the 11th inning. Harry Agganis walked, Jensen singled him to third base, and Olson singled for what proved the winning run in a 9-8 win. Olson was on a hot streak, but it didn’t last.

“The manager (in 1951 when he first came up, Steve O’Neill), he liked me, and I liked him. After that year, he was gone and Boudreau came in. We didn’t see eye to eye, but that’s one of those things. He was a Piersall boy. Piersall was a good player. I had about a 10- or 11-game hitting streak but he took me out of the lineup and put me in as a pinch-hitter. I guess … I wasn’t his type of player. Made some dumb mistakes, I guess. There was one incident in Chicago there, where I made three errors on one ball. Jim Rivera hit a ball right through the pitcher, over the pitcher’s mound. Truman Clevenger was the pitcher at the time. We ended up good friends because he lived out in Southern California here. It got out to me and it went through my legs. It was kind of a wet evening and the grass was wet so I went back to get it and it slipped out of my hand and it went backwards, and that happened twice. So you can imagine the look I got from Mr. Boudreau when I finally got back into the dugout. I got three errors.” The play occurred on June 25, and Olson was only officially charged with two errors, but Boudreau was likely in a bad mood after the 6-4 loss during which the Red Sox committed five errors in all.

Olson was good friends with Jensen. They roomed together for a couple of years, but they didn’t always travel together. Jensen disliked travel by air, and his “roomie” remembered what was likely Jensen’s last flight: “He flew one time. We played a night game in New York and we flew back to Boston which is not a long flight — but, boy, did we hit a storm! It was terrible. We had lightning and everything on our wings. Blinding. And Jackie was sitting behind me and by the time we landed and would get off the plane, his fingers were so sunk into the back of my chair that they could hardly release them. I think that’s the only time that anybody can remember that he ever flew. It was very unfortunate.” From what he remembered, other players actually had to help Jensen pry his fingers off the seat. “That was scary. Oh God, we didn’t know if we were going to make it or not.”

Early in 1954, Olson hit into another triple play. On April 24, at Griffith Stadium, he was up in the third inning with runners on first and second. He tried to bunt to advance the runners but popped up to Washington pitcher Mickey McDermott instead. McDermott threw the ball to the shortstop, who doubled off Tommy Brewer at second base, then fired to first to nip Billy Goodman. Olson tripled and scored in the same game, but the headlines were for Mel Parnell, whose arm was fractured by a pitch from McDermott. Brewer had been running for Parnell.

The Red Sox were hoping that “all the service rust had rubbed off” (a Hy Hurwitz phrase) and that Olson could contribute in 1955, but he saw much less action. He slammed into the concrete outfield wall at Sarasota’s Payne Park and suffered a mild concussion as well as abrasions to his left hand. He was back the next day, but with an outfield of Williams, Piersall, and Jensen, there just wasn’t much work to be had – and Olson got less of it than fellow reserve outfielders Gene Stephens and Faye Throneberry. Olson saw action in only 26 games, batting .250 in 48 at-bats. He drove in just one run all year long. After the season, Boston packaged Olson with pitchers Dick Brodowski, Tex Clevenger, and Al Curtis and outfielder Neil Chrisley in a November trade to Washington for infielder Mickey Vernon, pitchers Bob Porterfield and Johnny Schmitz, and outfielder Tommy Umphlett. The Senators projected Olson as their starting center fielder for 1956.

Karl worked as a milkman or dairy farmer in Oakland during the winter. Just as he was ready to return, he was hospitalized with pneumonia in February and it set him back at first. “I was going into spring training and I was still pretty weak and everything, so I had a pretty bad spring training until the last day. We faced Robin Roberts of the Phillies and I hit a home run, and then from then on I had a good streak for about a month. I was hitting in the .300’s or close to it toward the end. Playing center field all the time. Opening Day against the Yankees and Don Larsen, I hit two home runs, and went 3-for-5, [actually 3-for-4] but of course Mickey Mantle hit two and we lost the game. That was a big time in my career, to start for a team and to hit the two home runs.” In the one day, playing in front of President Eisenhower, Olson equaled his home run output for the Red Sox. Just the month before, he had blamed Fenway’s left-field Wall for his shortcomings in Boston; he said the Red Sox tried to make him a pull hitter to take advantage of the Wall and messed up his mechanics.

“I got hurt against Detroit. Instead of trying to slide — Red Wilson was the catcher — and he got the ball quite a bit in front of the plate. I figured I couldn’t slide because he had me blocked so I just tried to jump over. … He caught me with the glove, so I went head over heels and hurt my shoulder. I was incapacitated there for about a week or so. But I heard about it the next day at the meeting, too, from Charlie Dressen. He said, ‘Some guys don’t know how to slide.’ So I ended up. … It was kind of a struggle the second half of the season and Whitey Herzog and I split center field. … Jim Lemon was here in right field and he had a good season.” Olson hit .246 in 313 at-bats, with four home runs and 22 RBIs.

Olson began 1957 with Washington, but on the last day of April found himself a Detroit Tiger. With the Senators, he had accumulated 12 at-bats, with two hits. Oddly, on his way from Washington to Detroit, he was back with the Red Sox for a matter of an hour or two – something he first learned in 2007. On April 30, John McHale was appointed general manager of the Tigers. The Red Sox had purchased Olson back from the Senators earlier in the day for around the $10,000 waiver price, and McHale’s first move was to buy Olson from the Red Sox, sending them first baseman Jack Phillips, whom the Sox assigned to the San Francisco Seals.

Olson appeared in eight games for the Tigers, with two hits (and one RBI) in 14 at-bats, but after Detroit signed Steve Boros, Karl was sent to the minor leagues. “I went to Charleston first, and then Birmingham was in a pennant race or something and so they sent me down there to finish up the year. Johnny Pesky was the manager. That was it.” Though he was signed by Culiacan in the Mexican League in November, this was effectively the end of his career. “Ever since I got out of the service, things weren’t the same. I really struggled and it was getting to me. My big-league contact was sold to Charleston in the fall of ’57 and I just didn’t relish the thought of going back without the family. I just thought: It’s a struggle, I’m not having fun, I’d better get a job.”

Karl and Patricia had two children at the time. A third arrived later. They had moved to the Lake Tahoe area and Karl and his brother-in-law purchased two hamburger restaurants. The area was more of a seasonal destination at the time, and it was hard work – seven days a week and long hours. During the winters, they closed down the Hamburger Heaven restaurants and Karl did carpentry. Being just a few days short of the five years’ major-league service time he needed for a pension, he had withdrawn all his pension money, but then a letter arrived informing him that he was being credited the two years he’d been in military service. He raised the money to repay into the pension fund. “I didn’t have the money myself because we bought the restaurants, and they didn’t accept hamburgers, so I had to beg, borrow, and steal to get the money back in. But it worked out. It’s been a blessing.”

Five years in the hamburger business hadn’t brought the Olsons the same degree of success as McDonald’s, but when a contractor friend learned they were selling out, he invited Karl to come in as a partner in his contracting business. They worked together for about four years, and then “he decided he wanted to give up the contracting but because he was quite a bit older and through him I was able to get my contracting license. I ended up contracting for 25 years.”

In 1965, the Olsons moved from the Tahoe region a few miles away to Gardnerville in Nevada’s Carson Valley. They had three sons – Cary, Terry, and Jerry. All three boys played baseball, but two of them just “played at it.” Terry showed some promise and was signed to a minor-league contract by Washington as an outfielder – but in the end, it just wasn’t him. Patricia Olson worked as a homemaker, though while Karl had been overseas in the service, she had worked for Pepsi-Cola in Salinas for a while, for $5 or $6 a day.

Late in life Karl did not spend much time following sports, though he watched the Red Sox and the Giants occasionally. He sold off his construction company and moved back to the Lake Tahoe region, where he enjoyed retirement immensely. Karl Olson died of a stroke on Christmas Day, 2010, in Reno, Nevada. He was preceded in death by his son Terry, and was survived by Patricia, his wife of 59 years; and sons Cary and Jerry and three grandchildren.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited within this biography, the author consulted the subject’s player file and questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

An oral history interview with Karl Olson was done by Bill Nowlin on April 25, 2007 and is the source of otherwise-unattributed quotations.

Notes

Full Name

Karl Arthur Olson

Born

July 6, 1930 at Ross, CA (USA)

Died

December 25, 2010 at Reno, NV (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.