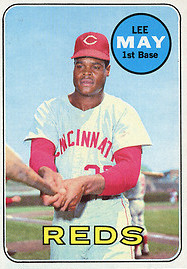

Lee May

One of the most feared hitters of his generation, Lee May is one of only 11 major leaguers to have 100-RBI seasons for three different teams. He also had 11 consecutive seasons (1968-1978) of at least 20 home runs and 80 RBIs. In an 18-year major-league career, the “Big Bopper of Birmingham” played for the Cincinnati Reds, Houston Astros, Baltimore Orioles, and Kansas City Royals. A three-time All-Star (1969, 1971, and 1972), he appeared in the postseason three times, including the 1970 World Series for the Reds and the 1979 Series for the Orioles. (The third was a Division Series in 1981 when he was with the Royals.)

May was a solid first baseman defensively (.994 career fielding percentage), but also struck out often (100 or more in ten seasons). What he was really known for, however, was his power. He slammed 354 home runs and drove in 1,244 runs the major leagues. He freely admitted, “I deliberately try to hit a home run every time up. That is what they pay me for.”1 Still, despite his power numbers, he lacks some recognition and, as sportswriter Jim Murray once wrote, “played in the undeserved obscurity of a bullpen catcher.”2

Lee Andrew May was born on March 23, 1943, in Birmingham, Alabama. His father, Tommy, who played semipro ball around Alabama, made mattresses and springs. His mother, Mildred, plucked and washed chickens in a poultry house. Young Lee held various jobs growing up in Birmingham, including delivering newspapers and office cleaning. Five years later, on May 17, 1948, the Mays welcomed another son into the family, Carlos, who himself had a ten-year career with the Chicago White Sox, New York Yankees, and California Angels. Lee and Carlos’s parents divorced, and Mildred and the two boys moved in with their grandmother.

Lee was a three-sport athlete (football, basketball, and baseball) at Parker High School in Birmingham. He was a forward for four years on Parker’s championship basketball team and a fullback on the football team, which won county and city titles. He was tall and hefty (6-feet-2 and 190 pounds), and as a youngster kept a birth certificate in his back pocket to prove that he wasn’t older than his teammates in little league.3

“They called me the Big Bopper,” he said in an interview with the author in 2011. “That was fine with me. I always wanted to be a home-run hitter when I was growing up. My favorite player was Harmon Killebrew. … I wanted to be just like Killebrew and hit a lot of homers. …”

May had scholarship offers from many colleges, including a football scholarship from the University of Nebraska. Baseball scouts showed interest in his talent, too, particularly his power. In the end, the Cincinnati Reds and scout Jimmy Bragan won him over. On his decision not to play with the Cornhuskers, May said, “Well, the Reds offered me money and I felt I had a better chance in baseball. Plus, I felt I’d have a longer career in baseball … and it was safer.”4

May’s grandmother also helped talk him into signing with the Reds, even after he signed a grant-in-aid at Nebraska. She argued that Cincinnati was close to home and their Double-A affiliate in Macon, Georgia, was not far from Birmingham. Bragan also sold the Reds to May’s grandmother when he said that he could make money right away and could attend college during the offseason. He received a $12,000 bonus from the Reds.

The Reds sent May to Tampa in the Class D Florida State League, where his manager was Johnny Vander Meer, of double-no-hitter fame. Vander Meer converted May from an outfielder to a first-baseman. “I threw side-arm too much for an outfielder and my throw would move too much from the target,” May said.5 Initially, he wasn’t on the roster, so he’d practice with the team and watch the game from the stands. “I didn’t feel like part of the club,” May said.6 Finally, he was placed on the roster and responded with a .260 average, no home runs, and nine RBIs in 26 games.

May played for Tampa again in 1962 and hit.260 in 89 games. He also played in the Florida Instructional League, and spent a semester studying at Miles College in Fairfield, Alabama. In addition, he played winter ball in Venezuela and Puerto Rico. “I actually planned on going to college (in the offseason), but I was always busy playing winter ball and it just got squeezed out. They paid you better in Puerto Rico and Venezuela than your own club paid you. … I made $350 a month in my first year in the minors and $1,500 a month in Venezuela that same winter.”7

May played winter ball for most of his first six years in baseball. He led the Puerto Rican league with 11 home runs in 1967-68. In 1969-70 he played in an outfield with Roberto Clemente and fellow Red Jose Cardenal, May called Clemente was an inspiration for him, saying, “I would try to apply some of Roberto’s ideas to my game.”

Besides gaining invaluable experience playing in the winter leagues, May needed the extra money to help support his family. In January 1962 he had married his high-school sweetheart, Terrye Perdue. Their first child, a daughter, Yelandra, was born that same year.

May moved up through the Reds’ farm system year by year, improving at each level. His manager at Rocky Mount in the Carolina League and Macon in the Southern League was John “Red” Davis, who corrected a flaw in his batting stance, allowing him to harness his power. “I was uppercutting the ball, and Red had me go into a semicrouch,” May said. The result was 18 home runs at Rocky Mount in 1963, 25 at Macon in 1964, and 34 at Triple-A San Diego in 1965.8 Don Heffner, who managed the Reds in the first half of the 1966 season, helped May improve his defense at first base while Lee was in the Florida Instructional League. “Every day he had me come out and for about an hour of doing nothing but fielding the balls he’d hit at me,” May said.9

At San Diego in 1965, May hit.321 with 34 homers and was named the Pacific Coast League MVP. May said his manager there, Dave Bristol, “did a great job teaching the fundamentals of the game.”10

May was a late-season call-up by the Reds, and made his major-league debut at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field on September 1, grounding out as a pinch-hitter. He played in five games, going 0-4 as a pinch-hitter. In spring training in 1966 he lost a battle with Tony Perez to be the Reds’ first baseman. On May 11 he was was optioned to Triple-A Buffalo. He hit .316 with 16 home runs, and was called up at the end of the International League season. Inserted into the regular lineup, he had two home runs and 10 RBIs. He got his first major-league hit on September 11, a double off the Phillies’ Chris Short, and his first home run on September 24, off the Mets’ Bob Shaw.

As the 1967 season began, May filled in at first base and in the outfield. Lee was initially used as a utility player, covering first base and the outfield. Then first sacker Deron Johnson was benched because of injuries and inconsistent play, and May got the job. In 127 games, he batted .265 with 12 home runs and was named The Sporting News Rookie of the Year.

May maintained a hot bat for a club on the rise, a team that would ultimately become the Big Red Machine. In 1968 May hit .290 and led the team in home runs (22). In 1969, the first year of divisional play, Cincinnati improved to 89-73 and a fourth-place finish in the National League West. May batted .278 and finished third in the league in home runs (38), and fourth in RBIs (110, a career best). In 1969 he made the first of his three appearances in the All-Star Game. The others were in 1971 and 1972. (In 1969 and ’72, Lee’s brother Carlos was on the American League squad.)

The 1970 Reds, led by rookie manager Sparky Anderson, won 102 games and finished first in the National League West, 14½ games ahead of the Los Angeles Dodgers. May’s batting average dipped to .253, but he slammed 34 homers and drove in 94 runs. (May hit the last home run ever at Crosley Field, in its final game on June 24, 1970.) In the National League Championship Series, May was 2-for-12 with two RBIs as the Reds swept the Pittsburgh Pirates. In the World Series May hit.389 (7-for-18) with two doubles, two home runs and eight RBIs, but the Reds were vanquished by the Baltimore Orioles in five games. May’s achievements were appreciated by teammate Johnny Bench, who said, “… (A) lot of people never realized how important he was to us when we won the pennant in ’70. …We were stumbling around late in the year because we were all tired but Lee was hitting home runs almost every day. And when we died in the Series, he was a one-man gang. …” 11 May’s eight RBIs in a five-game World Series tied a 1910 record held by the Philadelphia Athletics’ Danny Murphy

May had a career-high 39 home runs in 1971, but the Reds slipped to fourth place. And after the season he was traded with infielder Tommy Helms and utilityman Jimmy Stewart to the Houston Astros for Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Morgan, pitcher Jack Billingham, outfielder Ed Armbrister, infielder Denis Menke, and outfielder César Gerónimo to the Reds. May and Morgan were the central pieces of the deal. The Reds wanted more speed in Morgan, who had stolen 40 bases in 1971, while the Astros wanted a true slugger in their lineup like May. He called the trade a surprise to him, “because I had such good year in ’71 and had been named the MVP of the Reds.”12

May spent three seasons with the Astros and supplied the power they were looking for: 29 home runs in 1972, 28 in ’73, and 24 in ’75. On June 21, 1973, he became the second player in Astros’ history (after Jim Wynn) to hit three home runs in a game. On December 3, 1974, he was traded with outfielder Jay Schlueter to the Orioles for top prospect Rob Andrews, a second baseman, and Enos Cabell, an infielder-outfielder. May was a perfect fit for Orioles’ offensively minded manager, Earl Weaver, who was famous for his philosophy of “waiting for the three-run homer.” Weaver said of May, “He’s a guy who likes to hit the ball as hard as he can every time he goes up there … and when he’s doing it, he can be destructive.”13

The Big Bopper’s Orioles career started just as Weaver liked it. He hit a home run in his first official at-bat, a three-run shot on Opening Day off Joe Coleman of the Detroit Tigers in the first inning of a 10-0 win for Baltimore at Tiger Stadium. May had a good first season with Baltimore, hitting 20 homers and driving in 99 runs. The team finished in second place in the American League East, 4½ games behind the Boston Red Sox.

The Orioles finished in second place again in 1976 and ’77, and fourth in 1978, before winning the pennant in 1979. By then, May was sharing the slugging spotlight with future Hall of Famer Eddie Murray, as they shared time at first base and as the designated hitter. Despite healthy power numbers for each season (27 homers and 99 RBIs in 1977, and 25 homers and 80 RBIs in 1978), May’s playing time began to decline. As age and injuries caught up with him, 1979 was the last season in which he would play in at least 100 games. He had only two pinch-hitting appearances in the World Series as the Orioles fell to the Pirates in seven games.

May played in only 78 games for the Orioles in 1980 (.243, seven home runs), and his six-year career with Baltimore ended when he became a free agent after the season. He signed with the Kansas City Royals and played in only 26 games in 1981 as a designated hitter, pinch-hitter, and backup first baseman. On June 8 May got the 2,000 hit of his career, off the New York Yankees’ Dave Righetti. In 1982 he played in 42 games. The Royals released him after the season and he retired as a player, with 2,031 hits. He became the Royals’ hitting coach and was part of Kansas City’s 1985 world championship team. For several seasons, he was on sort of a shuttle between his former teams, coaching first base for the Reds in 1988 and 1989, returning to the Royals for 1992 through 1994, and coaching with the Orioles in 1995 and ’96. Finally, he returned to coach first for one more time in 2002, this time with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

May was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame in 1998 and the Reds Hall of Fame in 2006. In 2009 he was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

Carlos May had a ten-season career with the Chicago White Sox, New York Yankees, and California Angels. He hit only 90 home runs, but he and Lee May are sixth all-time in home runs by two brothers (444). Carlos in 2012 was the minor-league hitting coordinator of the Seattle Mariners.

As for Lee, he said in 2011: “I now do PR with the Reds and have eight grandchildren who keep me and my wife pretty busy.”14

Postscript

Lee May died on July 29, 2017.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Lee and Terrye May for their time and generosity. Besides sources noted in the endnotes, other sources included the Lee May file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, baseball-reference.com, and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Arnold Hano, “Lee May, the Man Behind the Astros’ Surge,” Sport, August 1972, 70.

2 Jim Murray, “Lee May Does His Job,” Fredericksburg (Virginia) Free Lance-Star, May 30, 1972.

3 The Sporting News, November 18, 1967.

4 Author’s Interview with Lee May, August 17, 2011.

5 Cy Kritzer, “Most Dangerous in the Clutch? Bisons’ Lee May Likely Choice,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1966.

6 Hano, “Lee May.”

7 Mark Ribowsky, “May Gives Orioles Edge In AL East,” Black Sports, August 1975, 50.

8 Kritzer, “Most Dangerous in the Clutch.”

9 Ritter Collett, “There’s ‘Mo’ On The Way: See Exciting Future for Reds’ Lee May,” Baseball Digest, December 1968, 92.

10 Author interview with May.

11 Ribowsky, Black Sports, August 1975, 49.

12 Author’s interview with Lee May, August 17, 2011.

13 Jim Henneman, “May’s HR Speak ‘Oriole Talk,’ ” The Sporting News, August 9, 1975.

14 Author’s interview with Lee May, August 17, 2011.

Full Name

Lee Andrew May

Born

March 23, 1943 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

July 29, 2017 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.