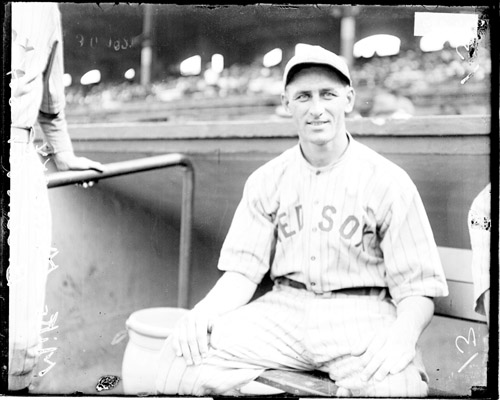

Mike Menosky

Perhaps there is something quintessentially American about the son of Slovakian immigrants, a ballplayer nicknamed “Leaping Mike” Menosky, who started his baseball career with a team named the Pittsburg Filipinos and who became the man the Boston Red Sox played in left field the first couple of years after Babe Ruth was sold to the Yankees.

Perhaps there is something quintessentially American about the son of Slovakian immigrants, a ballplayer nicknamed “Leaping Mike” Menosky, who started his baseball career with a team named the Pittsburg Filipinos and who became the man the Boston Red Sox played in left field the first couple of years after Babe Ruth was sold to the Yankees.

Joseph and Elizabeth Menosky both came to the United States from what today is Slovakia, Joseph arriving in 1882 and Elizabeth six years later. They had at least eight children – listed in the census by the names Joe, Mike, Maggie, Charley, Mary, Lizzie, Emily, and Paul. Eighteen years after he came to America as a 19-year-old, Joseph was working as a day laborer in 1900 in the small but growing coal town of Glen Campbell, Pennsylvania. The town is 15-20 miles away from the home of legendary groundhog Punxsutawney Phil.

Joseph Menosky had ambition, and success, becoming the agent of a brewing company by 1910 and ten years later appears to have owned a retail grocery and family store. It was a close-knit family. Even as late as 1920, every one of the children still lived in the household and three of them are listed as working in as retail grocers and merchants, as manager and clerks.

Mike had himself been a laborer in a coal mine in 1910, born in Glen Campbell on October 16, 1894, and age 15 at the time of the census. By 1920, he was a major-league ballplayer taking over for the aforementioned Babe Ruth.

Menosky attended college and played baseball at the Indiana State Normal School, now known as Indiana University of Pennsylvania. At the time, it was essentially high school for him, since he progressed from ten years of elementary school to “college” and never went to high school.1 He first started playing professional baseball in 1913, when he was 18. He played for two teams, both of them only briefly: eight games at third base with the Allentown club in the Tri-State League (batting .167 with four hits in 24 at-bats) and an unknown number of games with the Pittsburg Filipinos, the nascent Federal League team named for its manager Deacon Phillippe, six-time 20-game winner who had helped lead the Pittsburg Pirates to the National League pennant in 1901, 1902, and 1903. The Filipinos’ first season only lasted 26 games, essentially a month. Playing a full season in 1914 Federal League, the team renamed itself the Pittsburg Rebels (after new manager Rebel Oakes). Menosky moved to the outfield – where he played the rest of his career – and he hit for a .264 average in the 68 games in which he appeared. His team finished seventh. Only one player in the league was younger, yet even early in the season Manager Oakes saw something in Mike. He was a 5-foot-10, 163-pound left-handed hitter and, Sporting Life reported, “Oakes believes that he has one of the national game’s coming stars in Mike Menosky. He is a college youth, being just 19 years of age at the present time. He has all that should make a great player. A fast runner, being able to do a hundred yards in a trifle over 10 seconds, youth, build, a good throwing arm and brains…Menosky is showing improvement every day. He is a left-handed sticker and all his smashes are on the line. One thing which stands out above all in Menosky’s work is the fact that he is there with the sand. There is nothing that resembles a drop of yellowness in his entire make-up and next year he should be one of the best outfielders in the league.”2 Menosky was a student at the Indiana (Pennsylvania) Normal School and he resumed his studies after the season.

Mike only played in 17 games for Pittsburg in 1915 and only had 21 at-bats. For most of the year, he played in New Haven for a team called the White Wings, in the independent Colonial League. In 77 games, he hit for a .258 average. He signed with Pittsburg again for 1916, but the Federal League folded. Instead, Menosky’s contract was purchased in February by the Minneapolis Millers. He was initially farmed out to the Duluth White Sox of the Northern League, where he appeared in 26 games and was leading the league with 58 total bases. He was recalled to Minneapolis on June 10. Menosky played in the American Association, hitting .264 with 11 home runs. Later in the year, he first appeared in the American League, getting into 11 games with the Washington Senators. His average was .162.

Menosky excelled during spring training in Augusta and made the Senators in 1917, even though the team was well aware he was of draft age (under 25 at the time) and could be taken into the service. The world war was underway and the military needed men; on May 31, he registered for the draft. Elmer Smith started in left field for Washington but less than two weeks into the season was replaced by Menosky. His speed counted for a lot, both afield and on the basepaths, and shared headlines more than once with 23-game winner Walter Johnson, though his average was .258 and his production middle of the pack for the fifth-place Senators – though he’d distinctly improved at the plate as the season progressed.

He got the call to military service in early December and wrote from his home in Flint, “I sure am ready.”3 He was inducted into the United States Army and served proudly in the infantry, in France. In July 1918, Baseball magazine ran a photograph of Menosky in his Army uniform and a letter he had written to editor F. C. Lane, which read in part:

Dear Mr. Lane: I believe it is every man’s duty, with American blood in his veins, to do his bit in this great world war. I am one of those men anyway and that accounts for the fact that I am here. I must say that playing baseball is considerable of a snap compared to soldiering. But I have forgotten the past or at least pushed it to one side temporarily and am really getting to like my new job. I have found that my previous experience as a professional baseball player has been of great service to me. In the first place a ballplayer is in good physical trim to start with. Then he is familiar with discipline and knows the advantage of team play which discipline encourages….I believe I had it in me to become a successful player and was making progress when the call came. Of course I would like to see what I could do in the big leagues after I had really got into my stride. But it is idle to speculate about the future in so uncertain a game as war.

Sincerely, M. W. MENOSKY. Late of the Washington Club.

Menosky saw combat action in France and lost considerable weight, but with the end of the war was able to plan to return to the United States in time to take part in the 1919 baseball season.4 He was discharged from the Army on April 21, and without any spring training appeared in the Opening Day game just two days later. He played a key role, scoring the only run of the game as a pinch-runner in the bottom of the 13th inning as Washington beat the Athletics, 1-0. He appeared in 116 games and hit for a .287 average, with six home runs. He had clearly not lost a thing despite missing the full 1918 season. At some point in his career, he earned the nickname “Leaping Mike” because of his fearless willingness to crash into and climb outfield walls in the pursuit of the ball.

Right at the end of the year, Washington traded Menosky to the Boston Red Sox. The Sox got left-handed pitcher Harry Harper, infielder Eddie Foster, and Menosky for the outfield. Braggo Roth, an outfielder, and Maurice “Red” Shannon, infielder, were traded to Washington. The Red Sox had sold their left fielder to the New York Yankees. They need a man to take Babe Ruth’s place, and there was some enthusiasm for their new man. The Boston Globe ran a photograph of Menosky under the headline “MIKE MENOSKY, NEW ACE IN THE RED SOX ATTACK”.5 Menosky was indeed involved in a good number of Red Sox wins, and had a good year – his best – hitting .297 with career-high marks in RBIs (64) and runs scored (80). The Red Sox had finished sixth in 1919; they moved up a notch to fifth place in 1920. Babe Ruth’s stats, however, were nearly off the charts.

In 1921, Menosky had another good year, with an even .300 average, 77 runs scored, and 45 RBIs, and 1922 was a solid season, too: .283, 61 runs scored, 32 runs batted in. Mike only appeared in 84 games in 1923, with Ira Flagstead, Joe Harris, and Dick Reichle handling the lion’s share of the outfield duties. He hit just .229, but committed 10 errors in just the 49 games he played in the field for a .920 fielding percentage. One of those errors he was glad to accept, however. A ball hit at him in the eighth inning of the September 7 game in Philadelphia was initially ruled a base hit by the official scorer. Players consulted with the scorer and the ruling was changed to an error; Boston pitcher Howard Ehmke finished the game without giving up a hit. Menosky served as captain of the Red Sox for one day, the final day of the season.

In late December, Boston released him to the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League. There was no one on the Vernon roster the Red Sox asked for in return, but the deal gave them the right to claim a Vernon player at some time in the future.6 Menosky had played in 810 major-league games and hit for a .278 average, with a .364 on-base percentage.

He had a very productive year for Vernon in 1924, hitting .328 with 15 homers in 154 games. On February 18, 1925, his contract was sold to the Rochester club in the International League. He hit .297 over the course of 108 ballgames.

On January 28, 1926, he was traded to Columbus (American Association) and hit an even .250 in 64 games. The following year, he played in Class B baseball for the Spartanburg Spartans of the South Atlantic League, hitting .267. And he married Ethel Barbara Steade in September.7 His final year in organized baseball was with the Binghamton Triplets in 1929. He hit for a .281 average in 473 at-bats.

In his life after baseball, Menosky worked in Detroit as a probation officer, a position from which he retired.8 There’s more to the story, though. Working in the corrections system was stressful, his wife explained in her letter to researcher R. W. Lindsay: “After he quit baseball, he had a wonderful life in the courts. He investigated all the cases coming before the judges, [essentially recommending whether to] put them on probation, fine them, send them to the workhouse – it was really a very trying job. When he retired he was happy to be able to rest. He also had sandlot teams of young boys in the [American] Legion.” His wife explained that he was just short of his 85th birthday at the time she was writing, and that Mike had suffered a nervous breakdown about ten years earlier and was on some days not himself, so it was she who was writing, but that he was very appreciative of the interest.

SABR researcher Al Kermisch wrote in the Baseball Research Journal how Menosky’s baseball background helped decide one case. Robert Melson, 21, had been charged with malicious destruction of property (breaking the window in a Detroit terminal caboose) by throwing a rock. The distance in question was 250 feet, and when Judge O.Z. Ide, who’d once played first base for Kalamazoo College, heard that outfielder Menosky couldn’t throw a rock that far, he dismissed the case.9

Menosky died at the age of 88 in a Detroit hospital on April 11, 1983.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Menosky’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Brian Morrison for additional information.

Notes

1 Mike Menosky player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

2 Sporting Life, June 6, 1914. The August 22 issue of the publication re-stated the same prediction regarding Menosky’s future.

3 Washington Post, December 11, 1917

4 Washington Post, January 30, 1919

5 Boston Globe, April 13, 1920

6 Boston Globe, December 21, 1923

7 An interesting note she wrote to R. W. Lindsay, and which is in Menosky’s Hall of Fame file, explains that her family name was originally Steed, but her mother changed it. She herself may have re-sequenced her own first and last name, since she says in the letter she was Barbara Ethel Steade.

8 The Sporting News, May 2, 1983

9 Al Kermisch, “Mike Menosky, former major league player, called upon to settle court case,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 31, 2002.

Full Name

Michael William Menosky

Born

October 16, 1894 at Glen Campbell, PA (USA)

Died

April 11, 1983 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.