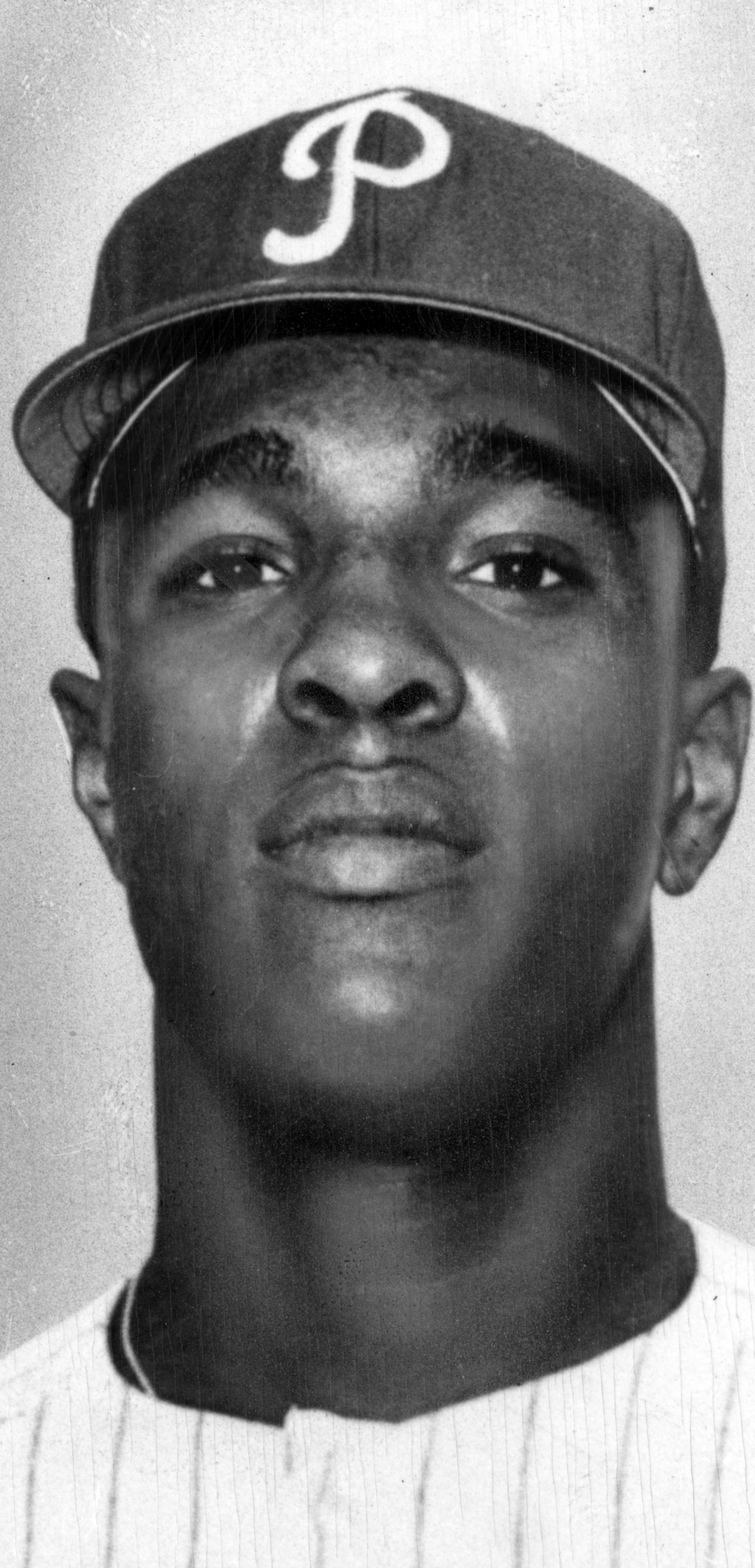

Alex Johnson

In an era when baseball players, collectively and individually, began to clash with management as never before, it is likely that no one clashed more than Alex Johnson. Though he was blessed with much-coveted talent, teams that employed him tired of him fairly quickly. The winner of a batting title, his emotional disability was at the center of one of the landmark cases in the early days of the players’ union.

In an era when baseball players, collectively and individually, began to clash with management as never before, it is likely that no one clashed more than Alex Johnson. Though he was blessed with much-coveted talent, teams that employed him tired of him fairly quickly. The winner of a batting title, his emotional disability was at the center of one of the landmark cases in the early days of the players’ union.

Alexander Johnson was born December 7, 1942, in Helena, Arkansas, and moved to Detroit as a small boy. Alex grew up with his parents, two brothers, and two sisters. His father, Arthur Johnson, Sr., worked in an auto plant, and later started his own truck repair and leasing company, doing a lot of work for the city’s public-school system. Ron Johnson, five years younger than Alex, was an All-American football halfback for Michigan and an All-Pro for the New York Giants.

Alex played football and baseball on the Detroit sandlots, along with future major leaguers Bill Freehan, Dennis Ribant and Willie Horton. At Northwestern High School, Alex was an offensive lineman, and earned a football scholarship to Michigan State University. A prep teammate of Horton’s, Johnson starred in baseball as well, and chose that sport because, as he put it, “I figured I could do better quicker in baseball.” Tony Lucadello, a scout for the Phillies, signed him in the fall of 1961.

Johnson sped through the minor leagues, starring in three venues along the way. He began his apprenticeship in 1962 playing for Miami in the Class D Florida State League, hitting .313 to win the league batting title and leading the circuit with 19 outfield assists. The next year he starred for Magic Valley (Twins Falls, Idaho) of the Class A Pioneer League. He was voted the league’s MVP by hitting 35 home runs with 128 RBIs (both league-leading totals) to go along with a .329 batting average. In 1964 Johnson was hitting .316 with 21 home runs for Triple-A Little Rock when Philadelphia recalled him in late July. He was just 21.

By this time Johnson had developed a reputation for his defensive struggles (in spring training the Phillies’ players had kidded him by calling him “Iron Hands”) and it is likely his defense kept him from getting promoted earlier. The first-place Phillies, who had been vulnerable to left-handed pitching, platooned Johnson with Wes Covington in left field. Nicknamed Bull for his powerful physique, Johnson hit close to .400 for his first six weeks, before cooling off to .303 as Philadelphia ultimately folded in late September.

Johnson was modest about his early success: “I’ve been lucky. I’ve been hitting mostly against left-handers and you don’t see many of those in the minors.” About his problems in the outfield, Alex allowed, “I see a fly ball coming and I hear all those people yelling, and I get a little tense. When you get tense … it’s easy to drop a fly ball.”

After the season Johnson played ball in Puerto Rico, which he later claimed caused him to wear down late in the 1965 season. He platooned again with Covington, and lost his .300 batting average over the last weekend of the season, settling for .294. As Johnson continued to hit, he began to play against an occasional right-hander, so that he ended up garnering 262 at-bats in 97 games. His defense improved enough that manager Gene Mauch played him in center field nine times. However, Mauch had also grown increasingly frustrated by Johnson’s perceived lack of effort and poor attitude.

In October 1965 the Phillies dealt Johnson, pitcher Art Mahaffey, and catcher Pat Corrales to the St. Louis Cardinals for first baseman Bill White, shortstop Dick Groat, and catcher Bob Uecker. Since White and Groat were both regular players for a team only a year removed from a World Series title, and since both Mahaffey and Corrales were marginal players, this swap was an indication of how highly regarded Alex Johnson was. The Cardinals compared this deal to the one they made in 1964 that had landed Lou Brock, envisioning Johnson on the verge of stardom. He had certainly impressed the Redbirds in 1965, hitting .424 against them. Manager Red Schoendienst vowed to play him every day. General manager Bob Howsam was all praise: “He has all the pluses to be an outstanding hitter. He can run, throw, and hit for both power and average. He is also powerfully built. He has a bright future ahead of him.”

To make room for Johnson, Schoendienst moved Brock to right field and installed Johnson as the team’s new cleanup hitter. Unfortunately for the Cardinals, Johnson did not live up to these lofty expectations. He began the season with 16 hits, only three for extra bases, in 86 at-bats. In May Johnson was demoted to the team’s Tulsa farm club in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, where he remained for the rest of the season.

At Tulsa, manager Charlie Metro said, he “just put Alex in the starting lineup and told him he would stay there.” Johnson hit .355 with 14 home runs in 80 games. Chief Bender, the Cardinals’ farm director, was impressed: “(Johnson has) real good baserunning instincts and terrific speed. He’s a pretty good fielder now, too. In fact he did a pretty good job in center field at Tulsa,” Bender said. Johnson appeared to be back on track.

Back in St. Louis, Johnson began 1967 in a platoon with newly acquired Roger Maris in right field. He started the season in a slump again — 3-for-29, a .103 clip — and by the end of the season (.223 with one home run in 175 at-bats) was playing little. He did not get off the bench in the 1967 World Series, in which the Cardinals defeated the Boston Red Sox. Not only was Johnson’s production inadequate, but he had once again worn out his welcome.

Dick Sisler, the Cardinals’ batting coach, was at the end of his rope: “He easily could have become a great Cardinal player, but he showed no interest, even at clubhouse meetings. He doesn’t seem to want to improve. He has tremendous speed, but he is not a good baserunner. We tried everything to bring out his potential. I was disappointed in not being able to get through to him.” Johnson would ignore teammates who motioned to him to shift his position in the outfield. He did not run out groundballs. He supposedly walked out during the clubhouse meeting to divide World Series shares. Late in the season he had a brief tussle with Bobby Tolan, a young teammate.

In January 1968 the Cardinals decided they had had enough and dealt Johnson to the Cincinnati Reds for part-time outfielder Dick Simpson, just two years after Johnson had landed former All-Stars Bill White and Dick Groat. Schoendienst was ready to move on: “Alex just might put everything together one of these days and become quite a ballplayer.” Johnson was happy for the change, saying of the Cardinals: “We disagreed on the way I should hit.” When asked how the team wanted him to change, Johnson admitted, “You’ll have to ask them. I didn’t pay any attention to what they told me.”

Johnson flourished with the Reds and manager Dave Bristol. Though he still did not smile or talk much, he hit .312 (fourth in the league), though with little power (two home runs) or plate discipline (26 walks spread over 634 plate appearances). The Sporting News named him its Comeback Player of the Year. Bristol had only glowing reports about his new left fielder: “All I can say is that I’ve found him to be one of the most cooperative players on the club. When I’m talking in a clubhouse meeting, there’s Alex looking me straight in the eyes. On the field, you never see him sitting down.”

Most baseball people figured that Alex just needed to be left alone. If you told him to hit a certain way, or field a certain way, he might ignore you or even do the reverse. If you said nothing, he might just figure it out himself. If his attitude was criticized, he retreated further. Bristol left him alone. When asked by a writer how Bristol differed from his previous managers, Johnson responded, “Basically, all those blankety-blanks are the same.” Or words to that effect.

Gene Mauch, one of the “blankety-blanks,” was always convinced of Johnson’s abilities: “There’s nothing Johnson cannot do in a baseball uniform that isn’t major league. If a manager can find a way to do it, he’s got a great player.” Also, “I told Alex one day that he should be making $40,000. And you know what he told me? He said, ‘Skip, I don’t need that much money.’ ”

Johnson was a fearsome-looking hitter. He was a big man (6 feet, 205 pounds) who looked larger than he was because he was muscular, stood right over the plate, and glared out at the pitcher. His bat speed was legendary. While hitting against a pitching machine, Johnson often stood 20 or 30 feet in front of the plate and hit line drives as his teammates watched in awe. Mauch believed he was the fastest right-handed hitter in baseball from home to first. In the field, he was a speedy outfielder with a powerful throwing arm.

In 1969 Johnson finally began to hit with the power long predicted for him, blasting 17 home runs while hitting .315. His teammates were not only impressed with his strength, but also with his incredibly calm demeanor no matter how he was hitting. Pete Rose commented, “You can almost bet Alex will never have ulcers. Nothing ever worries him. If he goes hitless a couple of times, he just changes bats and keeps swinging.” In fact, he was known to change bats constantly, wielding a club as large as 43 ounces.

On November 25, 1969, the Reds dealt Johnson, infielder Chico Ruiz, and pitcher Mel Queen to the California Angels for pitchers Jim McGlothlin, Pedro Borbon. and Vern Geishert. General manager Howsam was reluctant to give up Johnson but felt that his team had a surplus of hitting, especially right-handed hitting, and needed help on the mound. In the event, McGlothlin won 14 games, rookies Bernie Carbo and Hal McRae split Johnson’s old job in left field, and the Reds won 102 games.

The Angels were delighted to acquire Johnson, as the 1969 team had finished dead last in the league in runs. Lefty Phillips, the Angels’ manager, beamed, “We have taken the first step in the right direction to strengthen our hitting, and I believe we made a fine deal.” General manager Dick Walsh was “elated to get a hitter of Johnson’s caliber.” They would both change their tune soon enough.

In 1970 Johnson was all the Angels could have hoped for offensively, as he hit .329 to win the American League batting championship. He captured the title by getting two hits on the last day of the season to pass Red Sox star Carl Yastrzemski, .3289 to .3286. Johnson was removed from the game right after he got the hit that put him in front – an event that caused some controversy, especially in Boston. Nonetheless, his 202 hits were a franchise record until Darin Erstad topped it in 2000, and his batting title remains unique in team history.

Unfortunately, hitting heroics were not the whole story for Johnson in 1970, as he was fined several times for failing to run out groundballs and for lazy play in the outfield. In September Phillips commented, “It’s as if he doesn’t consider it a hit unless the ball reaches the outfield. It’s as if he has zones marked off in his mind, and unless the ball goes into one of these zones, he’s just not going to run hard to first base.”

As if that weren’t enough, Johnson also repeatedly screamed obscenities at teammates and media members who tried to speak with him. Writers, having long given up dealing with Johnson, sent a letter to Walsh asking that the slugger be kept away from them so that they could interview his teammates. Johnson’s wife reportedly apologized to the other players’ wives for the way Johnson was treating their husbands.

When asked to compare Johnson with Richie Allen, the controversial NL star of the time, Phillips scoffed: “Once you get Richie Allen on the field, your problems are over. When Johnson gets to the field, your problems are just beginning.” Phillips tried to discipline him further, but Walsh, who liked Johnson’s bat and feared exacerbating the team’s anti-black reputation, failed to back him up.

Perhaps the most frustrating thing with Johnson was that he seemed utterly unaffected by disciplinary actions. The players had a “kangaroo court,” which held mock trials to fine a player for offenses like not wearing a hat properly or being late for batting practice. Johnson, not wanting to be bothered with such nonsense, simply wrote a check for $500 and asked that it be applied to future abuses. One Angel player commented that “Alex wouldn’t be good for us if he was hitting .400.” Nevertheless, Phillips believed that Johnson had begun to lighten up in the final weeks of the season and hoped the batting title, and its accompanying acclaim, would help Johnson see that the world was not all aligned against him.

The 1970 Angels finished 86-76, an improvement of 15 wins from the year before. After the season the Angels made several big trades and landed outfielder Tony Conigliaro, who had driven in 116 runs for the Red Sox; Ken Berry, a fine defensive center fielder; and Jim Maloney, one of the premier pitchers in the National League over the previous several years. The national media were predicting big things for the 1971 team.

Team harmony began unraveling in spring training. In a March 20 exhibition game, Johnson spent a hot day in left field by moving with the shadow of a light tower rather than assuming his proper defensive position. When he failed to run out a groundball in the first inning the next day, Phillips removed him from the game. Since it was only an exhibition game, the Angels hoped it was an isolated incident. Johnson was also unconcerned, reasoning, “I don’t really like to play in the spring-training games. … I go down the batting cage because that’s the only way I can get the type of batting practice that I want.”

Johnson began the season hitting well, and was named the team’s player of the month for April. This proved an illusion. Over the next several weeks, he was fined every few days, a total of 29 times by late June, and was benched five separate times. Phillips later said that he could have fined Johnson every day, but he began to look the other way to avoid confrontations. Phillips told the press: “He did things differently last year. He gave about 65 percent. Now it’s down to about 40 percent.”

Johnson was completely unconnected with the rest of the team; he sat alone on the bench, neither shaking hands with nor speaking to his teammates. Outfielder Billy Cowan claimed: “We’ve had meetings, we’ve pleaded with him. We’ve asked if it’s anything we’ve done. He doesn’t say anything.” The contradiction with his nature outside of the ballpark was bizarre. As team owner Gene Autry said, “Off the field, you can not find a nicer guy. He doesn’t drink, smoke, or carouse at night. It just seems that when he gets into uniform he is a different guy entirely.”

In a game in Chicago, Johnson allowed a blooper to fall in front of him in left field. When asked about it later, Alex said, “The average guy in the league couldn’t have had it. Me, I could have – if the circumstances had been right. I have nothing to defend myself against.” When asked repeatedly to offer any sort of excuse for his attitude, he demurred, once saying, “I would have to cut some people. I don’t want to do that. Baseball is a team game.”

Johnson was benched on May 15 for failing to hustle, and again on May 21. Two days later, he jogged after a fly ball that landed in front of him, and then did not run out a groundball. Exasperated, Phillips finally called a clubhouse meeting without Johnson and told the team that Johnson would never play for the Angels again as long as Phillips was manager. The players applauded. Veteran pitcher Eddie Fisher told the press: “I won’t make excuses or protect him any more. … The whole thing just leaves you disgusted.”

In the meantime, general manager Walsh talked to Johnson, defended him to reporters, and asked Phillips to put him back in the lineup. Johnson was reinstated on May 26. Jim Fregosi later commented: “Lefty gained one player and lost the other 24 on that day.” After playing well over the next week, on June 4 Johnson failed to run out a groundball and was benched for four more days.

The handling of Johnson severely undermined the morale of the team. During one heated exchange, Ken Berry charged after Johnson in the clubhouse. In another, Clyde Wright raised a stool at him and had to be held back by his teammates. Johnson let it be known he was willing to fight anyone who wanted a piece of him.

After another benching a few weeks later, Johnson blamed the team for his attitude: “The club needs mental discipline and that involves a lot of things, but that’s all I am going to tell you about it.” When asked specifically about his pregame nonchalance, he defended himself: “Sometimes I take fielding practice instead of standing around the batting cage waiting to hit. Sometimes I have other things to do before the game, like working on my glove.” Responding to the charge that he didn’t hustle: “A person is supposed to run out groundballs. If I don’t, I just don’t.”

Chico Ruiz, a popular utility infielder for the Angels, had been great friends with Johnson while they were teammates in Cincinnati, and Ruiz was the godfather to Johnson’s daughter. At some point during the previous 12 months, Johnson had begun to torment and abuse Ruiz, screaming vile profanities at him whenever they crossed paths. Ruiz and his teammates claimed complete ignorance as to what had caused the rift. Oddly, Dick Walsh thought Ruiz was good for Johnson: “If Ruiz were not there for him to kick around, I don’t know what he’d do.”

On June 13 Johnson accused Ruiz of pulling a gun on him in the clubhouse during a game. (Both players had been used as pinch-hitters and removed from the contest.) According to Johnson, Ruiz had a gun in his locker and waved it threateningly. Ruiz denied the story and said he did not even own a gun. Nonetheless, a teammate was heard to comment, “If Chico did anything wrong, it was that he didn’t pull the trigger.” The next day, Walsh held a press conference to let everyone know that there was no evidence of a gun. The national media, already decidedly anti-Johnson, ridiculed him further.

In a rare interview, Johnson was blunt: “Hell, yes, I’m bitter. I’ve been bitter ever since I learned I was black. The society into which I was born and in which I grew up and in which I play ball today is antiblack.” Johnson blamed all of his problems on the insensitivity of his teammates, the “hypocrisy ” of Walsh and Phillips, and Ruiz, who was the “cause of the dissension. … I never knew a man to be so determined in a negative way.” When pressed to elaborate, he went no further. Johnson also claimed that he ran out groundballs the way he had his whole career. This may have been true.

Johnson also acknowledged the effect he had on his team: “The pitchers don’t pitch well when I’m in there. … When I’m playing, the spirit is down.” On the other hand, he had “justifiable reasons for not being in the spirit of playing properly. There was an indifference on the whole team in working together. I felt the game of baseball wasn’t being played properly – so my taste wasn’t there.”

When Johnson did not run out another groundball on June 24, Phillips benched him again. Finally, perhaps even mercifully, on the following day the Angels suspended Johnson indefinitely without pay for “failure to give his best efforts to the winning of games.” Most of his teammates thought that the suspension was long overdue. Jim Fregosi claimed: “He was given every opportunity.” Fred Koenig, a coach, was more direct: “I like Alex personally, but I despise him professionally.”

Remarkably, no one connected with the team seemed to consider that Johnson might need help. Conigliaro came the closest, saying, “He’s so hurt inside, it’s terrifying.” Dick Young, writing in the New York Daily News in late June, felt that Johnson was emotionally imbalanced, although Young stopped short of suggesting that he ought to be treated. In a fairly sympathetic column, Young was puzzled that Johnson could be “the most jovial, pleasant man you would care to meet” one day, and the next day “explode into plain nastiness. These are not moods, not in the accepted sense of normality. He is two people.” Nonetheless, Young’s advice was merely that Johnson right his own ship.

The Major League Baseball Players Association, led by Marvin Miller, filed a grievance on Johnson’s behalf, seeking to overturn the suspension and the fines. Miller suggested that Johnson was emotionally disabled, and ought to have been treated like someone who broke his leg. When Johnson’s 30-day suspension (the maximum length the Angels could dole out) was up, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn placed him on the restricted list, effectively suspending him for as long as Kuhn wanted.

The grievance was heard by Lewis Gill, an impartial arbitrator hired by the union and the commissioner’s office. Gill found for Johnson, determining that he should have been placed on the disabled list rather than being suspended. Two psychiatrists examined Johnson, one each selected by the union and the Angels, and they agreed that Johnson had been emotionally disabled, and therefore not able to give his best efforts. They were both of the opinion that, with treatment, he would be able to resume his career. (Oddly, although Gill found that Johnson was owed back salary by the Angels, he ruled that Johnson would still have to pay all of his fines, totaling $3,750.)

During his testimony at the hearing, Walsh admitted for the first time that Ruiz did wave a gun at Johnson back in June, feebly noting that it was not loaded. The general manager claimed that he withheld the information in the best interests of the team, and of Ruiz, who was not an American citizen and therefore could have had problems with immigration officials. Walsh’s deceit, which included calling up Johnson’s pregnant wife to tell her that her husband had become delusional, allowed the national media to ridicule his disturbed player for three months. Walsh also admitted in the hearing that he had told several Angels players that the players’ union requested that they testify. This, too, was a lie.

Marvin Miller later wrote extensively of these events in his memoir A Whole Different Ballgame. Miller interviewed Johnson at length during his suspension, and believed that Johnson was obviously emotionally disabled. In Miller’s view, Johnson had justifiable grievances (including racism) and was incapable of dealing with those grievances effectively. Miller did not hide his disdain for Dick Walsh. An enlightened baseball establishment, in Miller’s view, would have dealt with Johnson much more humanely. Miller said he believed this case was a watershed for the union, as it showed the black players that their issues would be dealt with just as a white player’s would be.

In early October 1971, Johnson was traded to the Cleveland Indians with catcher Jerry Moses for pitcher Alan Foster and outfielders Vada Pinson and Frank Baker. Gabe Paul, the Indians’ general manager, acknowledged, “Every trade is a gamble and we know the risks involved in this one. But if we can win on it, we can win big.”

On February 9, 1972, Chico Ruiz was killed in an automobile accident near San Diego. Alex Johnson was one of the few ballplayers to attend his funeral.

Johnson started off well for the Indians, but slumped dramatically in the second half to hit just .239 as the team’s left fielder. Graig Nettles, Cleveland’s third baseman, was not happy with his teammate: “He tried the first half of the year, but it seemed halfway through the year he just quit. Toward the end of the year, he bunted about eight times in a row, no matter what the situation. It looked like he didn’t have any pride in himself. … Everyone was just kind of disgusted at the whole thing.”

In March 1973 Johnson was traded again, this time to the Texas Rangers for pitchers Vince Colbert and Rich Hinton. Whitey Herzog, his new manager, was practical about the deal: “I don’t promise anything with Johnson but what we want him to do is come in here and hit. If he does that, we figure we got a good deal. … If he doesn’t come in and shape up in a hurry, we’ll release him.”

Herzog later wrote that he liked and admired Johnson. He acknowledged that Johnson was a terrible outfielder, but the AL had adopted the designated hitter rule, allowing Johnson to DH in 116 of his career-high 158 games. He rebounded with a .287 average and 179 hits, a new franchise record for the team that had started in Washington in 1961.

In 1974, under manager Billy Martin, Johnson was the regular left fielder for much of the year, and hit .291, though with his typical mediocre power (just four home runs) and plate discipline (just 28 walks). By early August he was mainly sitting on the bench, and on September 9 he was sent on waivers to the New York Yankees. Martin was candid when asked about Johnson: “I like him personally and I like him as a player. We never had a cross word. But I do make one demand of my players and that’s to run out all groundballs.”

The Yankees were in first place at the time and were looking for another bat as they tried to hold off the Orioles and Red Sox. In Johnson’s first game, on September 10 in Boston, he hit a home run off Diego Segui in the 12th inning to beat the Red Sox and extend the Yankees’ lead to two games. In the end, Johnson was just 6-for-28 for the Yankees, mainly as a pinch-hitter, as New York finished two games behind the Orioles.

The next season Johnson was back in New York, but was only a part-time player – 119 at-bats, mainly as a pinch-hitter or designated hitter – and hit just .261 with one home run. Late in the season the Yankees hired Billy Martin to be their manager, and soon thereafter placed Johnson on waivers. When asked about his relationship with Martin, Johnson was typically evasive: “You’ll have to ask him. He was the one who waived me. I didn’t waive him.”

In the offseason, Johnson signed with his hometown Tigers, a move that everyone hoped would finally motivate the rapidly aging 33-year-old. Detroit general manager Jim Campbell, overseeing the worst team in baseball, felt his team had nothing to lose: “We’re banking on the fact Alex is now playing in his hometown. That was something I noticed about him anytime he came here to play – he’d always bear down.” Johnson played in 125 games for the 1976 Tigers, 90 of them in left field, and hit a fairly hollow .268. The Tigers were an old team that was about to undergo a dramatic youth movement. Johnson was let go at the end of the season.

Johnson played a season for the Mexico City Reds of the Mexican League, hitting .321 in 54 games, before leaving baseball behind. By 1978 he was back in Detroit running his ailing father’s truck repair and leasing company. When his father died in 1985, Alex took over the company.

Alex married Julia Augusta on February 2, 1962, when he was still in the minor leagues. They adopted Jennifer in 1969 and had Alex Jr. in 1972. Alex and Julia divorced after his career in baseball ended.

Dick Allen, a teammate of Johnson’s in Philadelphia when they were both breaking into the major leagues, and another player given the reputation of being surly and uncommunicative, wrote of Johnson in his 1989 autobiography, Crash: “Why don’t you hear his name today? I’ll tell you why. Because he called everyone dickhead. To Alex Johnson, baseball was a whole world of dickheads. Teammates, managers, general managers, owners. … Alex would say, ‘How ya doin’ dickhead?’ Just like that. The front office types would take it personally. But then again, maybe Alex hit a nerve.”

In 1998 Sports Illustrated sent Jeff Pearlman to check on Johnson and see how he was doing. Alex was still angry about his baseball career, and how his managers and teams had treated him. He was glad it was all behind him. “Do I enjoy my life? I enjoy not being on an airplane. I enjoy not having to face everything I did. I just want to help people with their vehicles. It’s a nice normal life – the thing I’ve always wanted.”

Postscript

Alex Johnson, 72, died on February 28, 2015, in Detroit due to complications from cancer, according to the Detroit News.

A version of this biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

In preparing this article, I relied largely on Johnson’s large clipping file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Many of the clippings are unattributed. Most of them are from The Sporting News throughout Johnson’s career. Most of the quotes from Johnson in this article are from those articles. In addition to the clipping file, I used the following sources:

Allen, Dick, and Tim Whitaker. Crash (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1989).

Fimrite, Ron. “For Failure To Give His Best,” Sports Illustrated, July 5, 1971.

Hano, Arnold. “The Lonely War of Alex Johnson.” Sport, October, 1970.

Hano, Arnold. “Alex Johnson: Unloved Bat King,” in Ray Robinson, ed., Baseball Stars of 1971 (New York: Pyramid Books, 1971).

Lawson, Earl, “A.J. Of The Reds,” Sport, September 1968.

Miller, Marvin, A Whole Different Ballgame (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1990).

Pearlman, Jeff, “Catching Up With … Alex Johnson,” Sports Illustrated, March 10, 1998.

Schaap, Dick, “The Brothers Johnson,” Sport, March 1973.

Full Name

Alexander Johnson

Born

December 7, 1942 at Helena, AR (USA)

Died

February 28, 2015 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.