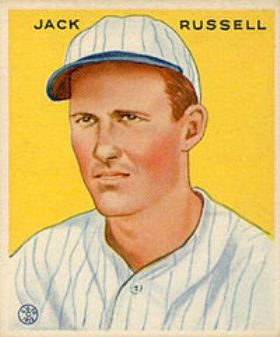

Jack Russell

From 1955 through 2003, Clearwater’s Jack Russell Stadium served as the spring-training home of the Philadelphia Phillies. (After he died in 1990, it became Jack Russell Memorial Stadium.) One would surmise that Russell, a right-hander who pitched in 557 games over the course of 15 seasons in the major leagues, must have been quite a star for the Phillies.

From 1955 through 2003, Clearwater’s Jack Russell Stadium served as the spring-training home of the Philadelphia Phillies. (After he died in 1990, it became Jack Russell Memorial Stadium.) One would surmise that Russell, a right-hander who pitched in 557 games over the course of 15 seasons in the major leagues, must have been quite a star for the Phillies.

One would be wrong. In fact, he appeared in only 17 games involving the Phillies – all pitching against them. When he did face the Phillies, he impressed: He was 3-1 with a 0.57 ERA, one win each in the final three seasons of his career, 1938, 1939, and 1940. From his 1926 debut with the Boston Red Sox through 1937, Russell pitched exclusively in the American League.

With a lifetime record of 85-141 and a career earned-run average of 4.46, Russell was never in great demand – witness that three times he was signed by a team as a free agent, decades before free agency was the norm and could typically be achieved only by being unconditionally released by a ballclub.

Russell began his career with the Red Sox and never had a winning record. He was 41-94 (4.58) with Boston, but worked six full seasons for the team, never working in fewer than 32 games. He led the league in losses in 1930, with a 9-20 record. This was a Red Sox team that couldn’t afford to be too picky as to pitchers. They were perennial losers, and the team’s winning percentage over those years wasn’t far from Russell’s own. His overall wins percentage with Boston was .303. The team’s, during his first six seasons, was .357.

Russell worked for six teams in all. Rarely did he have a winning record. He did twice make it to the World Series, however, something many players can never put on their résumé.

Jack Erwin Russell was born in Paris, Texas. His grandfather Tom was a truck farmer, and at the time of the 1910 census Jack’s parents lived with Tom and Annie Russell on the farm. Their son Will lived with them, too, along with his wife, Maud (Proctor). Will – given name Thomas William Russell – worked as a postman in the city of Paris, the county seat of Lamar County in the northeastern part of the state. He eventually became postmaster, the position he still held at the time of his death in 1946.

Will and Maud married on January 4, 1905, and Jack came along quickly, on October 24. They lived in Paris and Jack attended high school there. An early influence was White Sox pitcher Dickey Kerr, who coached the Paris High School team during the offseasons when Russell was a student. Kerr told him, “You’ll never have power enough to be a good enough hitter to hold down a berth as a fly-chaser, but with your height and long arms you may be able to make a pretty fair fast ball pitcher.”1 Russell worked at pitching and for his last two years in high school pitched for the Paris team on Saturdays when the team was at home. Russell was 6-feet-1 and is listed at 178 pounds (by mid-career – as late as 1930, he had weighed just 153 pounds.)2 Other pitchers who had influenced him (they had all pitched for Paris at one time or another) were Sam Gray, Wilcy Moore, and Mule Watson.

Russell attended Paris Junior College for two years. After he graduated, he played full time. Professionally, Paris was his first home as well – at age 19, he played in the East Texas League for the Paris Bearcats in 1925. He’s shown with a 7-11 record, working a hefty 189 innings.

On August 2 the Boston Globe reported his purchase from Paris, to report to Boston on September 1. The Dallas Morning News reported the price paid as $2,000.3 The Red Sox scout was Steve O’Rourke. “I heard one day that a big league scout was looking me over. Of course, I had a bad attack of buck fever and could not do anything right,” Russell said later. “We were playing Greenville and I lost 9 to 8, nineteen hits being made off me – and they were real hits – not scratches. Naturally, I figured that no big league club would care for me after such a terrible exhibition and I was the most surprised boy in all Texas the next day when I learned that Boston had bought me for $2,000.”4 It appears that O’Rourke had been tipped off by the Rev. Fr. Healy, a personal friend of Red Sox owner Bob Quinn.5

Russell joined the Red Sox for spring training in New Orleans in February 1926. It was a rainy spring training and at one point the hopeful prospect bemoaned the situation: “All winter I’ve been looking forward to the opportunity of showing my stuff to big league owners and along comes the rain to hold me back.”6 Russell made the team, and made his major-league debut for manager Lee Fohl on May 5 against the visiting Washington Senators. The Red Sox were losing 10-0 when he came in to work the eighth and ninth innings; he gave up five hits and one run, while Washington’s Stan Coveleski spun a four-hit shutout.

Russell’s first decision came in his first start, on June 9. It was a 6-4 loss, to the Browns in St. Louis. He was taken out during the fifth, having given up the first four runs. He never did record a win in 1926, finishing 0-5 on the season, but he did pitch at least one excellent game – working eight innings but losing 2-0 against the Senators on August 31. He was, once again, opposed by Coveleski throwing another shutout.

Come 1927, Russell lost his first four decisions. He was 0-9 in the major leagues until mid-June, more than 13 months after his debut. Finally, at Fenway Park on June 16, manager Bill Carrigan called him into a game after seven innings. The Indians were winning 9-7. Russell pitched a scoreless eighth, then happily saw his teammates score four runs in the bottom of the eighth. In the top of the ninth, he put two men on and got only one out so Carrigan called in Red Ruffing to relieve. One of the runs scored, but the 11-10 margin held up and Russell got credit for the win.

In his July 18 start, Russell gave up five runs in five innings, but the Red Sox scored 14, so he got a another “W.” His other two wins (against nine losses in 1927) were a 5-2 complete-game win over the Yankees and a 3-0 shutout of the White Sox, both in September. The Red Sox, as they had in 1926, finished in last place. They did again in 1928, though Russell won 11 games, second on the staff. He ended the season with a 1-0 complete-game win. But he lost 14. Russell also contributed a career-high five RBIs, a total he matched three other years, but never surpassed. On August 17 he drove in the winning run of his own game with a two-out single to left field in the bottom of the 11th for a complete-game 4-3 win over the White Sox. He wasn’t much of a hitter, however, a lifetime .167 batter.

Russell lost 18 games in 1929, winning only six, despite an ERA under 4.00 (3.92). The problem was typically run support. He lost his last four decisions, during which the Red Sox scored a total of only six runs. On September 10 he managed to lose both games of a doubleheader against the Browns, giving up four runs and being pulled after one inning in the first game, a 6-1 loss, and then working the complete second game, but losing 1-0.

The 1930 season was notable for two particular things in Russell’s career – he led the league in losses. With a 9-20 record, he was that rare 20-game loser (his ERA had risen to 5.45). He tied for the honor with teammate Milt Gaston (13-20), another right-hander. And Russell hit, on August 3, the one and only home run of his career. There was no one on at the time, so he got only one RBI out of it; it was one of the four runs he drove in during his 35 games and 229 2/3 innings pitched. The homer was hit off Washington’s Bobby Burke and was the final run of the game in a 7-1 win over the Senators at Griffith Stadium.

By 1930 Russell was half-owner of a grocery store in Paris. And he married “Gainesville society girl” Florence Elizabeth Dial on November 24 in Gainesville.7 Russell still had another year and a half to play for the Red Sox.

In 1931 it was more of the same. Russell’s ERA was over 5 (5.16) and he lost 18 more games, though this time he won 10. The Red Sox finished in sixth place, the highest they’d finished since 1921. Remaining injury-free, Russell pitched the most innings of his career – 232.

It was in 1932 that Russell first moved on to another team, and he was traded twice. He began the season with the Red Sox, and was off to a poor start (1-7, with a 6.81 ERA) when he was traded to the Cleveland Indians on June 10 for pitcher Pete Jablonowski (who later changed his name to Pete Appleton). The Boston Globe allowed that Russell had more or less stalled out in Boston and “for the past two or three years he appeared to be going backward.”8 What did Cleveland see in Jack Russell? The Plain Dealer said, “Russell has been regarded one of the several Red Sox hurlers who might be a consistent winner with a stronger club.”9 He lost his first two decisions with the Indians, but then righted his ship and was 5-7 for them by season’s end, with a 4.70 ERA during his 18 appearances for the Tribe.

Cleveland really wanted Washington first baseman Harley Boss, and in December found a way to get him. On December 15, the Indians traded Russell, first baseman Bruce Connatser, and cash to the Senators. Joe Cronin’s Washington team was happy to secure Russell. Though Cronin admitted that Russell was just a “fair pitcher,” he did note that Russell had been particularly successful against the Senators, winning four games from them in 1932 alone – “as far as the Washington club is concerned, he looked like Grove out there on the hill. A change of scenery may do him a lot of good.”10 Over the years, he’d won 16 games against the Senators, which was impressive since he had only 30 wins against all the other clubs combined.

It proved to be a good trade for Russell and the Senators. In 1933 he pitched to a 2.69 ERA and was 12-6. He worked almost exclusively as a reliever (starting only three times in 50 appearances), with only one of the 12 wins coming in a game he started. He also had a leagueleading 13 saves. And Washington won the American League pennant, finishing seven games ahead of the second-place Yankees.

In the 1933 World Series against the New York Giants, Russell pitched five innings of scoreless relief in the 4-2 Game One loss charged to Lefty Stewart. He secured the final two outs of Game Four, coming in to close the door in the top of the 11th inning after starting pitcher Monte Weaver had already allowed the Giants to edge ahead, 2-1. In Game Five, with the Giants already holding a three-games-to-one edge in the Series, it was 3-3 after six innings. Russell had struck out the last two batters in the top of the sixth, stranding an inherited runner on second base. All three Senators runs had come on a three-run homer by center fielder Fred Schulte in the bottom of the sixth.

Russell then worked a scoreless seventh, eighth, and ninth. But with two outs in the top of the 10th, Mel Ott hit a solo home run to center field, giving the Giants the lead. The Senators put two on in the bottom of the 10th, but couldn’t put one across the plate and Russell bore the loss as the Series came to an end.

The home run wasn’t without controversy. It had glanced off Fred Schulte’s glove as both he and the ball fell into the “low temporary stand that had been constructed in front of the regular pavilion”11 in center field, landing in the laps of some dismayed Senators fans. The ball was in fact initially ruled a double by the umpire closest to the play, second-base umpire Cy Pfirman. Umpires Moriarty and Moran conferred with Pfirman and overruled his call, declaring it a home run.

Leading the league in appearances in 1934, with 54, Russell was also named to the American League All-Star squad, in just the second All-Star Game ever played. He was not called upon to pitch.

Russell’s 1934 season was not a particularly good one. His ERA dipped to 4.17 and his record was 5-10. The team had plunged from first place to seventh place. And though the Senators nudged up a notch to a sixth-place finish, 1935 saw a further slide for Russell, to 5.71 (4-9). He was again kept busy, working in 43 games. He would have worked more but for a broken hand that sidelined him for 2½ weeks in July.

In the offseason Russell played some golf in Florida and on February 1 led the field in the Florida State baseball players’ tournament, with a first-round 74. Wes Ferrell ultimately claimed the lead and Russell finished fifth.12 It was Ferrell first and Russell second in the 1940 tournament. Finally, years later, in the 1950 tournament, Russell won the whole thing, though he had to play an extra nine holes – “extra innings” – to beat Ferrell.13 It was the first of several wins. Russell later became president of the Florida State Golf Association. In 1961 he won the American Seniors Championship.14

In 1936 Russell was a holdout in spring training, not wishing to take the cut Senators owner Clark Griffith felt was dictated by his decline, but in the end Russell capitulated.15

In his first 18 appearances of the 1936 season, he was running a 6.34 ERA (and was 3-2). Former manager Joe Cronin was now working for Tom Yawkey and the Red Sox and on June 13, the Sox traded pitcher Joe Cascarella to obtain Russell, bringing him back to Boston and reuniting him with Cronin. Russell had been used intermittently as a starter and reliever, starting nine games for Washington in 1934, seven games in 1935, and already five games in 1936. Cronin felt that by having Russell work exclusively in relief, he would pitch more successfully and, no less importantly, spare Cronin’s four principal starters from occasionally being asked to relieve. “I’ll never forget him in that ’33 season,” Cronin crowed, “He was positively marvelous as a relief pitcher. We’d have never won the pennant without him.”16

Russell later said that the main reason the Senators had been able to hold on and stave off the Yankees at the end of the 1933 season was a brawl that had broken out between the two teams earlier in the year. “We didn’t think we belonged up there with the Yanks, but when they started slugging in that free-for-all our awe of the Yankees left us.” For the rest of the season, “We pinned their ears back … and knocked them out of the race.”17

Russell was 0-3 (5.63) for the Red Sox. Nothing special. Well into spring training in 1937, he was released, on March 20. On April 4 he was signed as a free agent by the Detroit Tigers. He did not have a good year. He was 2-5, with an earned-run average of 7.59 and a WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) of 2.058. The Tigers released him in October.

In 1938 Russell trained on Catalina Island with the Chicago Cubs, and was not officially signed until shortly before the season began, on April 5. He had a good year (6-1), working in 42 games and with a 3.34 ERA. He also saw his second trip to the World Series, facing seven New York Yankees batters in 1? innings spread between Game One and Game Three. None of them scored, but the Yankees swept the Cubs.

In 1939 Russell had a similar regular-season ERA (3.67) with a 4-3 record. After the season, the Cubs let him go. He was picked up by the St. Louis Cardinals, signed in April, but he didn’t make it through the season. He worked in 26 games and had a very good 2.50 ERA (he was 2-3). A month after his last appearance, he was given his release on September 9.

Russell played some semipro ball, pitching for the Worcester (Massachusetts) All-Stars during the early summer in 1942. He found his way briefly back to the pros, signing in early July to play in the Piedmont League for the Portsmouth Cubs. He worked in 18 games (3-2) with a 1.85 ERA. That was his last-known time pitching in Organized Baseball.

Shirley Povich of the Washington Post wrote that Russell had been able to “overstay his time in the big leagues because he was a nice guy. … There were no superlatives to hang on him; he simply fit the label of an all around good guy, the kind a fellow likes to give a break.”18 Povich said that Russell had pitched with a dead arm since sometime in 1935. At the time Povich’s appreciation ran, Russell was “proprietor of Clearwater’s most prosperous filling station.”

Jack Russell Oil Co., Inc. was the base, but he later became distributor for the Pure Oil Company.

Russell was also active in civic affairs, serving as a city commissioner in Clearwater from 1951 through 1955. It was during that period that he inspired the construction of the ballpark in Clearwater. “One afternoon in July of 1954, when things were kind of quiet during a City Commission meeting,” he told the St. Petersburg Times, “I told the mayor (Herb Brown) that I had something to show them. I pulled out a big brown envelope, the blueprints for a baseball stadium that I had asked for from a construction friend of mine in Nashville who built stadiums. I told the Nashville guy that I had no money for the plans or the project, but if he would gamble with me and come up with the plans, maybe I could sell the idea to the City Commission.”19

The Commission went for it. Even so, Russell had not planned to attend the opening day festivities when the park opened the following year, but his wife urged him to go. It was then that he learned the stadium had been named after him.20

Russell died after a long illness on November 3, 1990, at Morton Plant Hospital in Clearwater. He left his wife and their son, Jack Jr.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Russell’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Hartford Courant, January 5, 1930.

2 Dallas Morning News, February 8, 1931.

3 Dallas Morning News, August 3, 1925.

4 Hartford Courant, January 5, 1930.

5 Unidentified news clipping found in Russell’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 Boston Globe, March 6, 1926.

7 Hartford Courant, November 25, 1930.

8 Boston Globe, June 11, 1932.

9 Plain Dealer (Cleveland), June 11, 1932.

10 Washington Post, December 16, 1932.

11 New York Times, October 8, 1933.

12 New York Times, February 2, 1926; Chicago Tribune, February 4, 1936.

13 Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1950.

14 Washington Post, January 22, 1961.

15 Washington Post, March 2, 1936.

16 Boston Globe, June 15, 1936.

17 Washington Post, March 13, 1942.

18 Washington Post, March 13, 1942.

19 St. Petersburg Times, November 4, 1990.

20 Ibid.

Full Name

Jack Erwin Russell

Born

October 24, 1905 at Paris, TX (USA)

Died

November 3, 1990 at Clearwater, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.