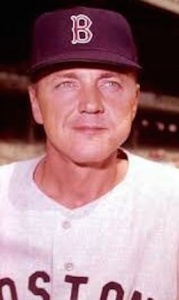

Len Okrie

Like a lot of young players who first came to professional baseball in the very early 1940s, catcher Len Okrie may have wondered if he’d ever truly have the opportunity to play, given the Second World War.

Like a lot of young players who first came to professional baseball in the very early 1940s, catcher Len Okrie may have wondered if he’d ever truly have the opportunity to play, given the Second World War.

He came from a baseball family. His father, Frank Okrie, was a left-handed pitcher who appeared in 21 games (one start) for the Tigers in 1920, with a 1-2 record and 5.27 ERA. He pitched in the minors from 1919 through 1923. Frank worked in Detroit as a motor assembler in one of the city’s automobile factories, and in a tire factory.

Frank’s parents came from “Poland Germany” and spoke German. Frank and his wife, Marie, raised four children – Dorothy, Frank Jr., Leonard, and Robert. Len was born in Detroit on July 16, 1923. All three boys played professional baseball in the 1940s, and all benefited from the time their father spent with them hitting them fungos and generally playing ball with them in the alley behind their house.1 Len considered himself “American-Polish.”2

Frank Jr. played shortstop from 1942 through 1949, with the three “war years” of 1943-45 out of baseball. He was in the White Sox system in 1942, then with the Boston Braves in 1946. He never got higher than Class C. He hit .269 for his time in organized ball.

Younger brother Bob Okrie was an outfielder, had a 4-F classification in the draft, and signed with the Chicago White Sox on March 7, 1944. He played through 1949 as well, from 1945 on in the St. Louis Browns system. He rose as high as Double-A in his final season, and had a career batting average of .293, but he died of leukemia in April 1950. Frank Jr. was stricken with polio.

Len also started in the White Sox system. He no longer recalls who signed him, but believes it was the same scout who signed both of his brothers.3 Len attended Goodale Elementary School in Detroit and graduated from Edwin Denby High School in 1941. He’d played sandlot ball and American Legion ball, and was a fan of Mickey Cochrane. There was nothing in life he ever wanted to do other than catch.4 “Catching is more fun,” he said. “You handle the ball more than anyone else and you can see more of the game than anybody else.”5 After agreeing to terms with the White Sox following graduation, he was sent to the Batesville Pilots in the Northeast Arkansas League but was released without appearing in a league game. Later in 1941 he signed a 1942 contract with Waterloo.

In 1942 he hit .194 in 31 games for Class-C Superior, Wisconsin, and .251 in 58 games in Class D for Lockport, New York. Then came the war. The three seasons of 1943 through 1945 saw Okrie in the United States Navy. There was some baseball during the war. In 1944, Okrie was Red Sox pitcher Charlie Wagner’s battery mate for a game between “District Headquarters” and “Marine Base” in San Diego. Okrie was on the Headquarters team. He spent most of the war working as a radioman, stationed on Adak in Alaska, where his unit bore Japanese bombardment on more than one occasion. There was heavy snow there as well, and the men in the unit needed ropes at times to make their way from the Quonset huts to the station.6

On a Lockport contract, he returned in 1946, though he spent most of the season with Statesville, North Carolina, in the Chicago Cubs system. He hit .248 in 77 games — not at all bad for a catcher. Most of 1947 was with Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he ultimately made his home. He hit .314 in 79 games in the Class-B Tri-State League. He played 24 games in Class A for Des Moines but hit. 208. At the end of the season, the Des Moines Register summed up his work: “Defensively, he is major league timber, but he will have to prove his worth as a batter.”7 He was on a Nashville contract, but was not protected, and in November 1947, it was reported that the Washington Senators had drafted Len Okrie from Nashville. In Fayetteville, he’d been scouted by Senators scout Mike Martin.8 He “came from the Chicago Cubs’ farm by draft.”9

Al Evans had hit .241 for the Senators in 1947; he was by no means a fixture on the ball club. Okrie made the Senators team out of spring training, but saw no action. A month into the season his contract was sold to Charlotte on May 18. He got his break in June when Washington catcher Al Evans had to have a minor mouth operation and backup catcher Jake Early suffered an injury to his right thumb from a foul tip. It wasn’t a fracture, but Okrie was called up to be ready if needed.

He was first called on to be a pinch-runner in the ninth inning of the June 16 game against the Browns, but was left stranded at third base in a 6-5 loss. His second appearance was in the second game of the July 5 doubleheader against the Athletics. Down 11-3, he was brought in to spell Al Evans and collected his first base hit, a single, in one of his two at-bats.

He collected hits in each of the next four games, too, and drove in his first run (his only RBI of the year) in a loss on August 2. He appeared in 19 games, often as a late-inning replacement, or a starter who was himself replaced; he only played in four complete games. He hit .238 in 43 plate appearances with just the one run batted in and one run scored. Defensively, he committed just one error in 54 chances. He might have hit better but apparently had been laboring with a stiff neck that required extended treatment over the winter months.

Okrie stood out in spring training 1949. Shirley Povich of the Washington Post wrote that Jake Early and Al Evans “have had a tight monopoly on the catching job with the Nats for most of ten years” but were “being crowded by Rookie Len Okrie in this year’s training camp.”10

Okrie had a sore throwing arm later in training. As it worked out, he spent much of the year in Buffalo, playing in 40 games, batting .214. He did not play in the majors. He was, however, rated by Buffalo manager Paul Richards as “the best defensive catcher in the International League.”11

In 1950 he played in 17 Senators games, all but two of them in August and September, batting .222. He drove in two. He handled 40 chances without an error.

In early February 1951, Washington let it be known they hoped to acquire Cuban catcher Mike Guerra, in part because they had recently signed three Cuban pitchers. As for Okrie, “He is generally recognized by the Nats’ bosses as the finest of all the catchers until he gets a bat in his hands. And then he is the weakest.”12 Senators skipper Bucky Harris said in late March, “If Okrie can hit .250 for us, I’ll stop worrying about my catching.”13 The Senators used him in five regular-season games (he hit .125, and also managed to commit three errors in 20 chances). On May 7 he was traded to Boston (along with $25,000) for Guerra.

The Sox used him to replace recently-injured Bob Scherbarth at Louisville. He played in 55 games in 1951 and hit .188.

When he wasn’t playing, Okrie worked with pitchers, learning things he could use as a manager and coach in later days. He threw a lot of b.p. over the years, fortunate in that he never once suffered a sore arm.

In 1952, Okrie played for three teams. He played for the Red Sox in the second game of the season, coming in defensively in the bottom of the ninth when the Senators were at bat. With two outs in the top of the 11th, a runner on second and the score still tied, 3-3, Okrie struck out. He set up behind the plate in the bottom of the 11th catching Ellis Kinder, who allowed a double and two walks, while retiring two, but saw the game lost when Floyd Baker hit a bases-loaded single to center. It was his last appearance in a major-league game, in large part because Sammy White was unexpectedly establishing himself as a big-league catcher. Okrie knew he was a good catcher but he was never nearly as good with the bat against major-league pitching. On May 11, Okrie was sent to Louisville. He hit .154 in 14 games, and on July 2 was acquired on option by the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres. There he hit .176 in 40 games.

Okrie played 1953 for Albany in the Class-A Eastern League, working in 91 games. In 1954 be began a managerial career, working in the Red Sox system. His first assignment was Bluefield, West Virginia, in the Appalachian League. He put himself into 22 games and hit .319, and helped the Blue-Grays win the league pennant and the playoffs. In 1955, Bluefield slipped to sixth place. He led the 1956 Lafayette (Indiana) Red Sox, another Class-D team, in the Midwest League, to a second-place finish. It was Greensboro in 1957 and Raleigh in 1958 and then two years for Corning in the New York-Penn League in 1959 and 1960. His father Frank Okrie died in October 1959.

Okrie was brought back to the major leagues in 1961, serving as Boston’s bullpen coach for two years. When new leftfielder Carl Yastrzemski struggled with the bat in April 1961, and was pressing so much that he was benched for a few days, Okrie spent considerable time with Yaz throwing to him so he could get extra batting practice. “He was my boy,” Okrie said in his 2015 interview. He was selected by Paul Richards to serve as batting practice catcher for the American League team in the All-Star Game.

Incoming 1963 manager Johnny Pesky elected to change most of the coaching staff and Okrie managed Waterloo in the Midwest League, now a Class-A circuit. In 1965 and 1966, with Billy Herman taking over as manager from Pesky, Okrie was brought back as the bullpen coach for the Red Sox, continuing to work with Red Sox players in any way he could. In August 1965 he suffered a broken jaw when struck by a Jim Gosger liner during batting practice; he had to have his jaw wired together.

With manager Dick Williams in for ’67, Okrie was out.

The Detroit Tigers hired him starting in February 1967 and he managed in their minor-league system for three seasons – first in Statesville and then for ’68 and ’69 in Lakeland. His last year in the big leagues was in 1970, bullpen coach for one year with the Detroit Tigers. Then it was back to the minor leagues for the Tigers for four more seasons – two in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, one in Anderson, South Carolina, and lastly for the Clinton (Iowa) Pilots in 1974. Okrie naturally had to play the players he was assigned; his teams never had a winning record after finishing 63-62 for Corning in 1959.

Okrie had done offseason work at a service station in the early years, but in later years and up to the time of retirement from baseball he worked as a clothing salesman at a men’s clothing store owned by a friend. He recalls he was a pretty good salesman. In the latter part of 1974 he became a deputy with the Cumberland County, North Carolina, Sheriff’s Department. He worked at the desk, taking calls and dealing with the public, a responsibility he enjoyed. He retired in 1986 as a sergeant. He and his wife traveled the country for a while and then when a Wal-Mart was built in Hope Mills in 1993, he worked for them as a greeter, retiring in 2005. For someone who enjoyed people as much as he says he did, it was another enjoyable position. During his time as a greeter, he received the Sam M. Walton Hero Award in 2000. Len lost his wife, Ileane (Russell) Okrie, in 2012.

As of October 2015, he was still living in Fayetteville, where he continued to receive weekly mail requests and letters for autographs from baseball enthusiasts – even one from a young baseball fan in Japan. He enjoyed memories of a life in baseball.

Okrie died on April 12, 2018, at the age of 94.

Last revised: November 4, 2023 (zp)

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Okrie’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Judy Horne.

Notes

1 Author interview with Len Okrie on October 26, 2015.

2 Len Okrie player questionnaire on file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Rod Nelson, chair of SABR’s Scouts Committee, says, “the smart money says that it was Pete Melito who signed Okrie for the White Sox in 1942.” Email from Rod Nelson, September 19, 2015.

4 Shirley Povich, “Nats Like Kid Catcher Named Okrie,” Washington Post, March 3, 1948: 19, and Okrie player questionnaire.

5 Shirley Povich.

6 Ibid., and October 26, 2015 interview.

7 Sec Taylor, “Quick Rise for Okrie,” Des Moines Register, undated late 1947 clipping in Okrie’s player file at the Hall of Fame.

8 Ibid.

9 Associated Press, “Nats Want Hitting Power,” Richmond Times Dispatch, March 3, 1948: 22.

10 Shirley Povich, “Okrie Crowds Early, Evans for Regular Catching Job,” Washington Post, March 10, 1949: 7. It was Povich who reported Okrie’s neck treatment.

11 “Robinson Gets Raise from Nats,” Washington Post, January 15, 1950: C16.

12 Shirley Povich, “Okrie Losing Out in Nats’ Catcher Fight,” Washington Post, March 8, 1951: C15.

13 Shirley Povich, “This Morning With Shirley Povich,” Washington Post, March 28, 1951: 15.

Full Name

Leonard Joseph Okrie

Born

July 16, 1923 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.