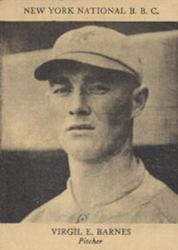

Virgil Barnes

On October 10, 1924, Virgil “Zeke” Barnes stood on the mound in Griffith Stadium, poised within tantalizing reach of a rare and coveted prize, just four outs shy of a Game 7 World Series win. Palpably close, but it was not to be. His moment of reckoning came with an improbable, aberrant bounce of the ball, a routine grounder gone awry, taking with it any hope of glory as it flew over third baseman Freddie Lindstrom’s head.

On October 10, 1924, Virgil “Zeke” Barnes stood on the mound in Griffith Stadium, poised within tantalizing reach of a rare and coveted prize, just four outs shy of a Game 7 World Series win. Palpably close, but it was not to be. His moment of reckoning came with an improbable, aberrant bounce of the ball, a routine grounder gone awry, taking with it any hope of glory as it flew over third baseman Freddie Lindstrom’s head.

John McGraw had selected Zeke Barnes that autumn day to carry the pitching burden for the New York Giants as the team faced the Washington Senators in its last-chance attempt to nail down a third world’s championship in four years. The honor of the starting assignment, combined with the game’s transfixing nature and instant stature as a classic, arguably made this contest the high noon of Zeke Barnes’ major league career. It would not, however, be the only time in his life that hard luck sided with a strong foe and Barnes’ story extends well beyond a single game.

Barnes first joined the New York Giants in the fall of 1919, and was added to the team’s roster on a full-time basis in 1922. At 6’0” and 165 pounds, he had “a good build for a pitcher, slender, tall and wiry.”1 His major league career—built largely on his curveball—lasted seven full seasons, all in New York except for a brief stint with the Boston Braves during his final year. Initially used as a reliever, the right-handed Barnes moved to the Giants’ starting rotation at the beginning of the 1924 season, and remained a starter for the balance of his 205-game career. At its conclusion, his record stood at 61-59, with an ERA of 3.66 in 1,094 innings pitched.

“An Atmosphere of Baseball”

Born on March 5, 1897 to Luther and Sarah “Sade” Barnes, Virgil Jennings Barnes2 was the third eldest of the seven Barnes children—four sons and three daughters—who would survive into adulthood. At the time of his birth, the Barnes family lived near the tiny northeastern Kansas town of Ontario (no longer extant). A few years later, they moved several miles south to the somewhat larger Jackson County community of Circleville, population 225, where Luther plied a variety of trades, including vegetable farmer, plasterer, railroad laborer and general laborer.

Luther Barnes raised his sons in “an atmosphere of baseball,”3 as Zeke would later characterize his upbringing. Luther had been an amateur pitcher in his youth, and his passion for the game shaped the early dreams and daily lives of his sons. All four of the Barnes boys—Jesse (“Jess”), Zeke, Charles, and Clark—would eventually receive tryouts with major league teams, and two, Jess and Zeke, would have major league careers.

Baseball was the dominant theme in the raising of the Barnes boys, but there were other influences as well. Music bonded the entire family. Zeke was a skilled cornet player, and during his teenage years, he played in Circleville’s cornet band. His mother’s artistic inclinations left a life-long imprint on Zeke. Sade was an amateur artist and her son would follow suit, eagerly sharing her interest in the creative arts, especially painting. Sade’s appreciation of the classics may also have been a factor in the selection of his name; one article published during Zeke’s career suggested that the Roman poet had been the inspiration for naming him Virgil.4

Barnes was a good student—his eighth grade marks were all in the high eighties and low nineties. He attended high school, but the four-year curriculum was a fairly recent introduction in Circleville at the time, and it is not known whether he graduated. Regardless of his graduation status, he must have been in a position to consider teaching as a career. In the summer of 1914, at the age of 17, he took the teaching certificate exam. Whether as the result of the 1914 exam or a later one, Barnes is believed to have earned a teaching certificate at some point.

If teaching was ever under serious consideration, it did not match the allure of baseball as a prospective occupation. Zeke played on Circleville’s town team and showed an affinity for the mound from the outset. By 1914, Barnes was not only a regular for Circleville; he was in demand by other town teams seeking to bolster their chances for success in county tournaments.

In 1915, when he was 18, Zeke got his first professional opportunity, probably with an assist from his older brother Jess. That summer, Jess excelled with the Davenport Blue Sox of the Class B Three-I League and earned a mid-season promotion to the Boston Braves. About the same time that Jess signed with the Braves, Zeke appeared on the Blue Sox roster. He finished out the season in Davenport, but with a lackluster record of 0-4 in seven games and an ERA of 4.88. That fall, he returned home to sharpen his skills.

The Circleville team was regarded as one of the best in the area in 1916, and it was a frequent entrant in featured matchups and tournaments where the best teams, often from rival counties, squared off to compete for cash prizes. Zeke, already known in northeast Kansas as one of the “famous Barnes brothers,” was Circleville’s marquee hurler.

By the late spring of 1917, however, the carefree afternoons of Zeke’s late teens gave way to more serious considerations. The country was at war, and Barnes had a decision to make. Zeke did not face immediate conscription, but he had a strong patriotic bent, and Jackson County’s National Guard Company was aggressively recruiting to reach full strength before the unit was federalized into active Army service. On June 2, 1917, Barnes responded, as had many others, to the recruitment plea and enlisted in Jackson County’s Company B of the Second Kansas Infantry.

The commitment he had made would soon change his life, but it did not immediately curtail his baseball activities. In fact, the next several weeks became an intriguing chapter in Barnes’ career. During this time, Barnes pitched for two multiracial teams—the widely-known and highly-regarded World’s All Nations team, and a lesser-known local copy, the Evans All Nations team, based in Horton, Kansas, about 25 miles northeast of Circleville.

When J.L. Wilkinson—who later founded the Kansas City Monarchs—and John Gaul organized the World’s All Nations team in 1912, the core concept was to take to the road with a team of players representing a variety of races and nationalities, and to earn a profit by successfully blending the popularity of baseball with the lure of the exotic. By 1917, when Barnes joined the team, the club’s winning ways and outstanding baseball credentials were firmly established. That summer, Barnes’ teammates included two future members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, both of whom hailed from Cuba—pitcher/shortstop José Méndez, the “Black Diamond,” and outfielder Cristóbal Torriente, the “Cuban Strongman.” The All Nations also featured John Donaldson, billed as the “Greatest Colored Pitcher in the World.”

Barnes’ first known appearance in an All Nations battery occurred in Kansas City on May 26, 1917. In that game, the All Nations defeated the St. Louis Giants by a score of 5-1. Shortly after the Kansas City outing, Barnes returned to northeast Kansas, where he pitched at least twice for the Evans’ All Nations nine, first in a contest against an Atchison, Kansas team and then against a team from Topeka. By late June 1917, Barnes re-emerged in the lineup of Wilkinson’s All Nations team as it barnstormed through Nebraska and eastern Wyoming. The newspaper trail of the team’s stops is still rather spotty, but Barnes is in news accounts of All Nations games in the Nebraska towns of Greenwood, Omaha, Beaver City, Cambridge, and Palisade, as well as Casper, Wyoming. It was in Casper that Barnes’ All Nations summer apparently came to an end. Wilkinson later told of the disruptive news that the team received in Casper, when several of its members, including Barnes, received orders to respond to a military summons.5 Some would have been called by their local draft examination boards following the national lottery drawing on July 20. In Zeke’s case, however, his order would have been to report to his National Guard unit in Jackson County to prepare for the unit’s activation. On July 9, President Wilson had announced that all Guard units would be drafted into federal service on August 5, 1917.

When the mustering-in process in Jackson County was completed in mid-August 1917, Private Virgil Barnes was counted in the roll of men comprising Company B of the Second Kansas Infantry.6 Upon mobilization, Company B reported to Camp Doniphan, a temporary Army training camp in Oklahoma. There the men from Jackson County became part of the 137th Infantry Regiment in the Army’s 35th Division.

Barnes’ talent as a cornet player landed him the job of bugler. It was a role he enjoyed, using the instrument to signal activities “important in the routine of Army life.” After training for six months in Oklahoma, the 35th Division embarked on its long journey to France, arriving in May 1918. During the division’s initial weeks in France, the troops engaged in additional training under the tutelage of the British. The division’s first combat zone assignments were in relatively quiet sectors, but sometime during those early months in France, Barnes had a close call. News made it back to Circleville that an artillery shell had exploded near Barnes, covering him with stones and dirt, but not injuring him.

The biggest trial for the 35th Division occurred in late September 1918, when it was one of the first to go “over the top” in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive—a battle that has since been characterized as the deadliest in U.S. military history.7 Barnes later talked briefly about his war experience, but in a way that understated the horrific conditions that he must have faced while on the line at Meuse-Argonne. Bugling, though part of the daily routine stateside, was not much used after the troops crossed the Atlantic. The title of Barnes’ grade did not change in France, but his duties did—he became primarily a communications runner, tasked with delivering messages from one command post to another, often over long distances. As he described it:

I carried messages, it seemed to me all over the country of France. I walked miles and miles and wore out shoe leather and kicked up more dust than a flivver8 crossing a stubble corn field. And this wasn’t merely unpleasant duty. It was, at times, decidedly dangerous….when I was very close to the front…in some well constructed dugout, I didn’t feel too happy when the Commanding Officer would say, ‘Here, take this dispatch over there.’ Walking is a healthy exercise, generally, but machine guns, to say nothing of stray shells don’t add particularly to its benefits.9

When he said he wore out shoe leather, he meant it literally. Tattered boots contributed to frostbite on his feet, which in turn created circulation problems that stayed with him the rest of his life.

On the third day of the Meuse-Argonne battle, September 28, the 137th Regiment advanced into an area known as Montrebeau Wood against a barrage of stiff German resistance. Not only did the Germans deliver heavy machine gun and artillery fire, they also, as one historian put it, “drenched the place” with gas.10 Barnes was one of those exposed, and he was hospitalized as a result.

When Barnes later talked about being gassed, he said he had been told that his case was not severe, but he also said that it had “made an impression on my memory which is likely to last.”11 The incident qualified Barnes for the wound chevron, a decoration awarded to soldiers injured in battle. World War I soldiers who earned a wound chevron were later entitled to exchange it for its current equivalent, the Purple Heart.12

The war ended shortly after Barnes’ injury, but his division remained in France until April 1919. In early May, the men in Company B returned to Kansas and were honored, as were the other soldiers returning that day, with a grand show of patriotic thanks in “the greatest military parade in Topeka history.”

Zeke, now 22 and eager to pursue his professional baseball career, wasted no time in returning to the diamond. Aided by a recommendation from his brother Jess, Barnes signed in early June with the Kansas City Blues of the Class AA American Association. John Ganzel, the Blues’ manager, set an optimistic tone when Barnes joined the team, calling Zeke’s fastball a “beaut,” but the move apparently was an overreach. Barnes’ chance with the team was over after only two innings in two game appearances. Barnes rebounded quickly, and by the end of June he was on the roster of the Sioux City Indians of the Class A Western League. He stayed with the Indians for the remainder of their season and compiled a 6-6 record in 26 games.

Jess, who was on his way to pitching a league-leading 25 wins for the New York Giants in 1919, had been talking up Zeke to his skipper, John McGraw. In late September, McGraw brought Zeke up for a look and, in the second game of a doubleheader in Boston on September 25, let him sip from his first cup of coffee. Barnes did not fare very well in that initial outing. In two relief innings, he allowed six hits that resulted in four runs. It may not have seemed a promising beginning, but John McGraw saw enough potential to bring him into the fold. On November 20, 1919, George Andreas, the president of the Sioux City club, announced that he had sold the rights to Barnes to the New York Giants for $3,000.

Barnes joined the Giants at their training camp in Texas in the spring of 1920, but was then optioned out to the Rochester, New York club of the Class AA International League. He became the Hustlers’ front-line hurler—the 303 innings he pitched was surpassed by only one other pitcher in the league, Jack Ogden of Baltimore. Barnes was among the league leaders in strikeouts, with 142,13 but on balance, it was a tough season. The team was not even close to being competitive, finishing with 45 wins and 106 losses. Barnes’ final record with the Hustlers was 12 wins, a league-leading 23 losses, and an ERA of 4.28.

Off the field, Rochester was more than just a temporary stop in a ballplayer’s odyssey, for it was here, in July 1920, that Barnes married his 23-year-old Kansas sweetheart. The petite and attractive Della Barnes (her maiden name was also Barnes) came from a large Jackson County family, the seventh of 10 children. Zeke and Della had postponed marriage until Zeke felt he had established a financial footing strong enough to support a wife. A major league career was hardly a foregone conclusion in 1920, but the timing of their marriage signaled optimism.

With the stint in Rochester thankfully over, Barnes rejoined the Giants toward the end of the 1920 season. He made his first start at the Polo Grounds on October 2, part of a Giants lineup largely populated with rookies. It was a meaningless game which the Giants lost, 4-2, to the Brooklyn Robins before a crowd of only 400. Zeke pitched seven innings, allowed nine hits and three runs, and took the loss.

During his early exposure to the major league game, Barnes found that he needed to make some adjustments. A crucial one, especially in light of McGraw’s attachment to the curveball, was adapting his curve to the aerodynamic properties of the “clean new balls” used in major league games. The curveball was a pitch Barnes thought he had mastered, but at first he was “helpless” in his attempts to make fresh balls bend in the same way as the worn, scuffed balls he was accustomed to using in lower levels of play. Barnes credited Slim Sallee, the veteran left-hander, with helping him regain command of his curve.14 Sallee also helped correct a pitching mechanics problem that had kept Zeke from powering his pitches with full force. The mentoring sessions with Sallee, whom Barnes called a “wise old pitcher,” likely occurred in the fall of 1920 and the spring of 1921, the only period when both players were with the Giants.

Barnes trained with the Giants again in the spring of 1921, and stayed with the team into early May before McGraw decided that he needed more minor league work. On May 13, the club announced that he had been released to the Milwaukee Brewers of the Class AA American Association. As a Brewer, Barnes pitched 259 innings in 36 games, had an ERA of 4.24, and a record of 17-15. He mounted an especially strong finish to the season, raising his stock in the process. In the space of a few days, Zeke pitched consecutive one-hitters. The first occurred in a game against the Blues in Kansas City on September 16, and the second, in a game against the Mud Hens in Toledo on September 20. The Brewers won both games by an identical score of 4-0. In an interview published in September 1926, Barnes pointed to his one-hitter against the Blues as “the best game I ever pitched.”15

“Ripe for the Big Tent”

In late January 1922, Zeke signed a contract to play with the New York Giants during the upcoming season. When he reported for spring training in 1922, the word was out that McGraw viewed him as being “ripe for the big tent,” and from the start he was treated as a regular. McGraw was ready to bring Zeke on board, but the manager’s plans for defense of the Giants’ world championship title did not include placing a rookie in the starting rotation. Except for two starts in mid-August, Barnes acclimated to major league life on a light diet of work from the bullpen, mostly in short relief. He finished the year with 51⅔ innings in 22 game appearances, an ERA of 3.48 and a record of 1-0. Perhaps he had not made the mark he would have liked in his debut season, but Barnes still had a steady spot on a championship team that was about to reassert its claim on the title.

As events unfolded, 1922 would be the only full season that Jess and Zeke Barnes would spend together on the Giants roster. Over the course of the season, the brothers appeared in the same game on nine occasions. Of those, Jess was the starter in six games and Zeke, in one. Jess was credited with one win and four losses and, by today’s accounting, Zeke earned a save. Their last joint appearance for the Giants was the most noteworthy. On September 24, both brothers pitched in relief of starter Rosy Ryan in a game at the Polo Grounds against the St. Louis Cardinals. Although the Barnes brothers were only two of four relief pitchers used in the game, they made history by each giving up “screaming homers” to Rogers Hornsby, who thus became the first major league batter to hit home runs off of a pair of brothers in the same game.16

The Giants’ successful defense of their title in 1922 would deliver to John McGraw his third and final major league championship. For the second straight year, the World Series was an all-New York affair in which the Giants prevailed over the Yankees. Zeke saw no action in the 1922 Series, but he was grateful when the team decided to give him what was, in essence, a full share of the winning spoils. His check for $4,545.70 was only one penny less than the amount received by the 18 Giants who received a full share.

Zeke’s eventful October did not end with his first World Series paycheck. Approximately two weeks after the Series ended, on October 21, Della delivered the couple’s first child, a son whom they named James.

Preparations for the 1923 season began with a showdown of sorts. Efforts by Milwaukee attorney Ray Cannon to organize a players’ union prompted an edict from the Giants’ management: any player who had not signed his contract would not be admitted to the team’s spring training camp and would be cut from the team’s roster. Zeke and Jess were among the holdouts, but they both decided to report to Marlin, Texas, the location of the Giants’ advance camp for pitchers and catchers. The Giants’ Hugh Jennings delivered the “veiled ultimatum” once again—either sign, or leave and be cut from the team. There was no hint of an opening for negotiation, and both brothers relented, as did the other holdouts, to keep their jobs.

Barnes soon encountered a personal hurdle. On the eighth day of the regular season and before he had entered his first game of the year, Zeke underwent surgery for appendicitis. When he had nearly recovered from the appendectomy, Barnes met with a second medical setback in late May or early June—this time, a tonsillectomy. Shortly after Zeke’s second operation, the Giants made a decision that affected the Barnes family. While the team was on the road in Chicago, the Giants’ management traded his brother Jess to the Boston Braves.

When Zeke returned to action on July 13, 1923, his role was much the same as it had been in 1922. All but two of his 22 appearances during the year were made in relief, usually after the cause had already been lost. His record was 2-3, with an earned run average of 3.91. The Giants, however, enjoyed another successful season in 1923, as the team captured its third consecutive National League flag.

For the third time in as many years, the World Series was a New York exclusive, but this time there was a different outcome. The Yankees prevailed, four games to two, by exploiting ineffective Giant pitching, especially during the latter half of the Series. Trouble among the Giant starters spelled opportunity for Barnes in Games 4 and 5, but in both cases, he entered the game with a several-run deficit. His team would not win either game, but he made the most of his chances. In the ninth inning of Game 4, he retired the side in order with 13 pitches. In Game 5, Barnes made a longer relief appearance: in 3⅔ innings, he allowed four hits, no runs, and no walks. In the bottom of the fifth, with two outs and two runners on base, he struck out Babe Ruth to end the inning.

The Series recaps did not toss many accolades in the direction of the Giant pitching staff, but a few took note of Barnes’ performance. The New York Times observed that Barnes had “…showed again that he can stand up with Arthur Nehf as the best of the Giant twirlers.”17 Heywood Broun, a New York sports columnist, went further, criticizing McGraw for not starting Barnes. In a post-Series column, Broun stated: “If McGraw had the daring and the imagination which distinguishes genius from mediocrity, he would have risked starting a game with young Virgil Barnes, who proved effective in the few innings he pitched.”18

With the opening of the 1924 season, Zeke’s role changed. No longer fated to be a fixture in the bullpen, Barnes was pegged as a starter from the outset. The decision to assign Barnes to the starting rotation was soon validated—in his first six starts, he compiled a 4-1 record. He would finish the season at 16-10, with an ERA of 3.06. Along with Jack Bentley, Barnes was the team’s co-leader in wins for the season, and he led all Giant pitchers in the number of innings pitched, with 229⅓. It would be Zeke’s best major league year.

In late June 1924, Zeke and his brother Jess registered a first in the major leagues. When they both started for their respective teams in New York on June 26—Zeke for the Giants and Jess for the Boston Braves—they became the first pair of brothers to face each other as starters in a major league game.19 Neither of them pitched well that day. Zeke was relieved in the first inning, and Jess, who took the loss, was relieved in the fourth. They met again only a few days later, on June 29, and gave a better account of themselves. Jess went the distance in leading the Braves to a 4-1 win. Zeke took the loss, but was replaced by a pinch hitter in the seventh, not driven from the game as he had been in their first match-up. Both brothers earned bragging rights in Boston later in 1924 by managing a Barnes sweep of a doubleheader, with Jess pitching Boston to a 5-4 win in the first game, and Zeke pitching the Giants to a 10-2 win in the second.

The Barneses’ sibling rivalry in 1924 was just a small sidebar in a Giants season where the big story line was the team’s bid for a fourth consecutive National League pennant. As the pennant race progressed, Zeke’s strongest showing occurred during the seven-week period between July 4 and August 21. Within this span, he registered seven wins in his 10 starts. His wins included a 7-0 shutout of the Cubs and, in what the New York Times thought was one of his better games, a 3-1 victory over the Pirates that showcased a curveball with “perfect behavior,” complete with “spin, a whirl and a dip.”20

He also won a game with his bat during this stretch, a rarity almost unheard of for Barnes. Zeke was a notoriously poor batter, hitting only .108 in his major league career. All of his hits were singles, and for years, he held the major league record for the number of at-bats registered without an extra base hit.21 However, his bat was productive in a 6-4 contest against the Cardinals in late July 1924, when his single to right field scored the winning run. It was one of only nine RBIs credited to Barnes in his entire major league career.

The Giants entered the final week of the 1924 season tied with the Brooklyn Robins for the lead, and 1.5 games ahead of the Pirates. To finish out, they faced a crucial three-game series with the Pirates, followed by a series with the Phillies. They won four of the five games, including a decisive sweep of the Pirates that eliminated Pittsburgh from the chase. Barnes made his final contribution to the pennant cause by pitching “a beautiful game” against the Pirates in the second game of the series, picking up his third win of the month in the Giants’ 4-2 victory. Three days later, on September 27, in the Giants’ next-to-last game of the season, the team clinched the pennant.

Although it was not publicly known until a few days later, a bombshell also detonated on September 27. During the pre-game warm-ups that day, reserve Giant outfielder Jimmy O’Connell, at the behest of coach Cozy Dolan, approached Heinie Sand, the Phillies’ shortstop, to offer him a $500 bribe if Sand would “not bear down” on the Giants during the game. Sand flatly refused and reported the incident to his manager, Art Fletcher, who in turn took it to National League President John Heydler and to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Landis completed his investigation quickly and acted decisively by banishing both O’Connell and Dolan from Organized Baseball. His action did not, however, erase the cynicism and doubts that had been created in the public mind.

Not only had the Giants’ public stock taken a dive, their Series opponent, the Washington Senators (often called the Nationals or Nats), was an improbable Cinderella team led by Walter Johnson, perhaps the most beloved sports figure of the time. With national sentiment building in support of the Nats, the Giants clearly would wear the black hats in the 1924 Series. They would come to be regarded, at least in a Sporting News headline, as “the most unpopular team ever” to play in the World Series.22

Just how unpopular became evident when the Series venue moved to New York and the team was abandoned by many of its own fans. Postseason play had opened in Washington, with the teams splitting the first two games by identical 4-3 scores. The next three games were played at the Polo Grounds, and New York sportswriter Joe Vila marveled at what he saw: crowds of 50,000 spectators, and “practically all of them pulling against the New York players!”23

Zeke joined the battle for the first time in Game 4, when McGraw chose him as his starter. Barnes had pitched more innings than any other Giant pitcher in 1924, and he was the team’s co-leader in wins, with 16. He received some recognition in the Series previews, with perhaps one of the most notable coming from Rogers Hornsby. In a column with his thoughts about the Series, Hornsby described Zeke as “exceptionally cool, [with] a good curve, and slow ball,” and credited him with having “pitched the best ball of all McGraw’s hurlers this year.”24 Yet, some sportswriters regarded Barnes as being something of a gamble because of his perceived inconsistency, and in this case, an “experiment” that could be made because the Giants had gained a 2-1 edge in the Series.

Game 4 did not go well for Barnes. His undoing started in the third inning, when he gave up singles to Earl McNeely and Bucky Harris and then a home run to Goose Goslin, leaving the score 3-1. His fate, and the team’s, was sealed in the fifth, when he allowed two more runs, one of which scored on a wild pitch. As in the third, McNeely, Harris, and Goslin were the primary villains. Barnes left the game after the fifth inning, and the Giants went on to lose the game, 7-4. The Series then was tied at two games each. Two games later, it was tied at three each.

The Series through Game 6 was all prelude, a path that needed to be traveled to reach the pièce de résistance. In the game that came next, the whiff of scandal was all but forgotten, at least for a day. This was a game destined for the ages, a game that would be heralded from that point forward as one of the “unquestioned classics of postseason play,”25 filled as it was with managerial maneuvers, tense moments, acts of fate, and a hero’s just desserts.

Zeke Barnes was the Giants’ starter in Game 7 and he was ready with his best stuff. He retired the first 10 batters he faced, and 18 of the first 19. Through 7⅓ innings, Barnes and his “sharp breaking curves” left the Senators “virtually helpless”; during that span, he “pitched brilliant ball” and was a “master pitcher” who allowed only three hits, one of which produced a run. It came in the fourth inning when Bucky Harris, the Nats’ 27-year-old manager and second baseman, lofted a long fly ball that “just did drop over the wall” into the temporary bleachers in left field. The score remained 1-0 until the sixth inning, when Barnes’ teammates delivered three runs for him. Given the quality of his pitching performance, it seemed possible that a 3-1 lead might be enough. It seemed possible, but only until the eighth inning.

The eighth started well enough with a foul pop out to the catcher, but then Barnes’ control faltered, and he pitched himself into a jam. He gave up a double, then a single, then a walk. With the bases loaded, the second out of the inning was recorded with a fly ball to left field, thankfully too short for the Nats to score a run. Next up was Bucky Harris. When Barnes saw the ball leaving Harris’ bat, his instinctive reaction must have been one of relief, for it looked to be a common, everyday grounder to the third baseman—an easy out to end a tough inning. Instead of obeying expectations, though, the ball took a wildly unexpected bounce off a pebble, stone, or clump of dirt, and sailed over rookie Freddie Lindstrom’s head into left field. It was scored a hit, and it tied the game at 3-3. Sportswriter Frederick Lieb called it “the luckiest break which ever came…to what looked to be a beaten world’s series team.”26 The Washington crowd—average fans blended together with an over-representation of dignitaries, up to and including President and Mrs. Coolidge—rose and erupted as one. Barnes, on the other hand, had been hit with the proverbial punch to the gut. In less than a heartbeat, the game, for him, was finished. He was relieved by Art Nehf, who retired the side with no further damage.

Walter Johnson, with two Series losses weighing on his mind and an arm short on rest, made an entrance in the ninth inning, amping up an atmosphere that was already supercharged. Both teams had their chances to break the tie, but it was not until the bottom of the twelfth inning that one of them did. With one out and two runners on base (courtesy, in part, of Giant errors committed by catcher Hank Gowdy and shortstop Travis Jackson), centerfielder Earl McNeely came to the plate and hit what appeared to be a routine grounder to Lindstrom. Remarkably, as Lindstrom advanced to field the ball, thinking double play all the way,27 it bounded beyond his reach with another erratic bounce. This time, the putative out turned itself into a double that scored an unearned run, winning the game and the Series for the Nats. The same improbable event had repeated itself within the space of a few innings. Sportswriter Grantland Rice summed it up this way: “The hit that tied it up and the hit that won were almost identical, perfect duplicates, as each reared itself from the lowly sod as if lifted by a watchful and guiding fate that had decided in advance that Washington must win.”28

In the aftermath, some kind words were written about Barnes’ pitching. In the opinion of one sportswriter, “Virgil proved that while all the great pitchers may come from his State they do not all come to Washington….Until [the eighth inning] he furnished the most brilliant bit of pitching seen in the series.”29 According to another article, Barnes earned the respect of the Washington players, who viewed him as the most impressive of the Giant pitchers and the one having the best curveball.30 And many years later, Grover Hartley, who was a reserve catcher with the Giants in 1924, said in an interview that Bucky Harris told him that “he was glad Barnes did not pitch more often in the series.”31

After the game, Barnes was in no mood for sympathy. He didn’t return to New York with his teammates, and went instead to Baltimore to catch the first train to Kansas. Zeke had another reason for heading straight home. Della had not been with him during the pennant chase and the Series, but had gone to Holton to await the birth of their second child. He had not received a telegram that had been sent nearly three weeks earlier to advise him that they had a new daughter, born on September 21. When he arrived home to find Della with their baby in her arms, he fainted straightaway, a brief surrender to the weight of recent events—the sustained stress, the anger, the fatigue, and probably the ill effects of too much bootleg alcohol on the trip home.

According to the story passed down within the Barnes family, there was speculation at the time that someone in the Giant organization might have intercepted the birth announcement telegram and deliberately chose not to deliver it to Zeke, one act in a broader effort to isolate the Giant players and shield them from distractions that would lessen their focus on the task at hand. Regardless of the reason for the missed communication, the delay in his learning about the birth created a problem. Because she had not heard from him, Della proceeded with naming their daughter, which became grounds for a row upon Zeke’s return. “Doris Fay” was not a name he took to, so their weeks-old daughter got a new one, Juanita June.

Zeke spent more than three additional seasons with the Giants, holding his position on the team’s pitching staff until June 1928. The Giants’ string of pennant victories ended in 1924, although the team contended at various stages in both 1925 and 1927. During his remaining tenure in New York, Barnes had a decent but not exceptional 40 wins against 38 losses in 90 starts. Two of the last three seasons with the Giants were winning ones. In 1925, Barnes went 15-11 and again led the team in wins; in 1927, he compiled a 14-11 record. The intervening 1926 season was a struggle. An injury suffered during a game against St. Louis cost Zeke five weeks of the 1926 season, even longer taking into account the time required to regain his form. Then, late in the season, he entered a prolonged slump and lost seven consecutive decisions.

The rivalry on the mound between Zeke and his brother Jess continued into 1927, which was Jess’ last season in the majors. Altogether, the Barnes brothers were on the opposite side of the same box score in 10 major league games.32 On five of those occasions, both of the brothers started for their respective teams. Of the 10 joint appearances, Zeke won three and lost four, while Jess won five and lost three.

During the later years in his career, Zeke appeared in anecdotal newspaper items that had something of a personal dimension. Two of these were small stories that revealed a playful nature. His skill at rubber-band shooting was good enough, for example, to knock the ashes from a cigarette being smoked by a startled teammate. There also was the unfortunate episode when his pet baby alligator, which he was prepping for a race, escaped from his custody and ended up in McGraw’s Pullman berth while the team was traveling north from spring training camp.

But the most famous, by far, of the published anecdotes about Barnes arose out of an incident that occurred in June 1925 during a road trip to Pittsburgh. The telling of the story had variations as to the details, but the gist of it is as follows. Zeke had been out carousing and missed curfew, probably (almost certainly) not for the first time. To get back into his room at the team hotel, he decided not to use the main lobby entrance but attempted to scale a fire escape instead. There was a mishap of some sort, and he sprained his ankle. The next day when he reported to the ballpark, he explained away the injury by saying that he had slipped in the bathtub. McGraw was suspicious—some accounts reported that Zeke’s room did not even have a bathtub—and challenged him about it. Zeke then admitted that yes, he had been attempting to sneak in after curfew. McGraw fined him $100, suspended him for violation of team rules, and sent him back to New York. The episode was widely reported, which in turn resulted in an unexpected bonus for Barnes. Upon his return to New York, a company that manufactured non-skid bath mats offered him $500 if he would provide a testimonial to be used in advertising their product. The sprained ankle story was a tale with staying power—references to it in print were made years later.

Zeke’s last decent season was 1927, with a 14-11 record. Perhaps his best major league game occurred on July 10, 1927, when he was “magnificent from the word go” in pitching a 5-0 one-hitter against the St. Louis Cardinals, the reigning world championship team. There would be a few more winning moments, but not many. By the beginning of the 1928 season, Barnes had definitely entered the difficult wind-down phase of his career. McGraw, who had sent out the first feelers of a trade in the spring of 1927, began to seriously look for trade options by early summer 1928. On June 15, 1928, the Giants dealt Barnes to the Boston Braves, along with Bill Clarkson, Ben Cantwell and Al Spohrer.

In his final major league season, Barnes’ ERA ballooned to 5.45 as he won only five games. Zeke had, as his family would come to say, “lost his arm.” During much of his last major league year, he pitched in pain. Ten years later, Barnes gave an indication as to the source of the problem. When Dizzy Dean was sidelined in the spring of 1938 with a widely publicized diagnosis of deltoid muscle inflammation that “probably result[ed] from subdeltoid bursitis,”33 Zeke said in an interview:

I suffered the same injury…and I had to retire. I never heard of a pitcher able to throw his best after suffering bursitis. Dizzy is now in the first stages of the ailment. Possibly he will return after a rest and begin throwing more balls underhanded and some curves. But his fast one is gone…he’ll probably have to quit the game—as I did.34

The final chapter in Barnes’ professional career carried something of a sad note. His last major league game was a relief appearance for the Boston Braves against the Cubs on September 15, 1928. The following December, the Braves announced that they were sending him to the Milwaukee Brewers of the Class AA American Association. After an unsuccessful attempt at a holdout to sweeten his contract, Barnes reported to the Brewers’ training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas. His stay with the team was a brief one, however. The Brewers had the option, through the end of April 1929, of returning Barnes to the Braves, and Zeke gave them reason to exercise it.

On April 6, Brewers’ manager Jack Lelivelt announced that he was returning Barnes to the Boston club because he participated in a “drunken brawl” at a dance hall while the team was in Knoxville, Tennessee, an altercation that resulted in Barnes being “badly beaten.” Zeke claimed that he was only trying to stop a fight involving a friend. Regardless of the underlying circumstances, Lelivelt meant to have “law and order” on his team, and the decision stood. In retrospect, the incident was an indication of the problematic role that alcohol had assumed in Zeke’s life, one that would continue to dog him in the years to come.

By the end of April 1929, Barnes had been shuffled to the roster of the Baltimore Orioles of the Class AA International League. He would pitch just 22 innings in eight games for the Orioles. His only win for the team—and the last win of his pro career—occurred on May 8, 1929, in a game against the Bisons in Buffalo. Zeke pitched a complete game and allowed six hits in the 6-1 win. In an odd twist, his brother Jess, who also was nearing the end of his playing days, appeared as a reliever for Buffalo in the game.

A short time later, Organized Baseball closed the book on Zeke Barnes. On June 12, 1929, his release from the Orioles became the last transaction to be recorded in his professional career.

A Thirty-Year Expanse

Barnes could not have known it at the time, but what lay ahead was a thirty-year expanse without a niche to replace baseball. There would be trials aplenty, and they would start almost immediately.

Had it been only his decision to make, Zeke’s inclination might have led him back to New York City at the end of his career. Della’s take was different, though. She came from a large, close-knit family, and the East Coast was simply too far distant to maintain family ties. So Zeke, Della and their two children settled full-time on the 80-acre homestead two miles southwest of Holton that they had purchased in 1928. The plan was to establish a farming operation and, indeed, Zeke’s occupation was described as “farm overseer” in the 1930 federal census.

The timing could hardly have been worse, coinciding as it did with the onset of the Great Depression. Moreover, there was an early encounter with devastating loss. Only three days into the new decade—on January 3, 1930—a fire took hold in the flue of Zeke and Della’s “large and well built” house. The Holton Fire Department responded to the emergency, but the water level in the home’s cistern was low, and the fire-retarding chemicals that were applied were inadequate for the task. In the end, some pieces of furniture and small incidentals were saved, but the entire structure was lost along with most of the family’s personal possessions.

The fire was an early omen of the changing tides about to engulf the family. Whatever wealth Barnes had accumulated during his major league years was quickly swept away by the Depression’s plummeting farm prices, shrinking land values, and bank failures. Signs of the worsening financial crisis for Zeke and Della appeared in 1932. First, they sold an 80-acre parcel of land northwest of Circleville that they had acquired early in 1930. Then, in August 1932, the Barnes homestead was placed on the block in a sheriff’s auction, the opening round of a multiyear bout to hold on to the 80 acres just southwest of Holton. The auction in 1932 was not the final and decisive blow, however. Zeke and Della were able to reacquire title to their property (although heavily mortgaged, to be sure), and there was a period of time when they likely benefited from a state law that imposed a moratorium on farm foreclosures. Clearly, though, the years of prosperity were behind them.

Even during a time of deepening financial turmoil, baseball had its place, and there were attempts to use it to generate income. In the late summer and early fall of 1930, the four brothers—Jess, Zeke, Charles and Clark—organized the Barnes Brothers All Stars team to play in a series of exhibition games. Charlie was the team’s manager and shortstop. The other three brothers shared the pitching duties and filled in where needed the rest of the time, with Zeke known to have played centerfield. The exhibition matches came to an abrupt end in Horton on October 12, 1930, when Clark collided violently with a teammate as they converged on a fly ball in the outfield. His teammate was not seriously injured, but Clark suffered major fractures to his leg and was hospitalized for several days.

Zeke’s last foray as a player came in 1932, when both he and Jess joined the Topeka Jayhawks, a semipro team managed by “Speed” Martin, formerly of the Cubs. The Jayhawks initially fared well, but their fortunes turned in early July. The team reneged on a commitment to play the Junction City, Kansas semipro team as part of that community’s Fourth of July celebration, failing to even notify Junction City of the change in plans. The Jayhawks opted instead to travel to Amarillo, Texas, where a local radio station had offered to sponsor their entry into a seven-team tournament beginning July 2. The goal in Texas was to finish strong and leverage Amarillo prize money into a trip to Denver to participate in the prestigious Denver Post tournament, slated to start in mid-July. Optimistic about their chances, the Jayhawks entered the Denver tournament but had to withdraw when the team was eliminated in Amarillo with a tourney record of 1-3. The team did not have the funds to continue, and returned home to Kansas instead.

Not a great deal is known about the next several years in Barnes’ life, but conditions in the Great Plains during the Depression were harsh. However, Barnes’ love of art and painting emerged with more emphasis during this time, and it would become a recurrent theme during the remainder of his life. Painting had been a longstanding avocation, inspired since childhood by the artistic interests and temperament of his mother Sade. He appears to have been largely self-taught, although he received some training and mentorship from Harry Gibson, a Baltimore sculptor whom he had known for a number of years. Zeke would eventually become most known for portraiture, but in the mid-1930s, Barnes painted murals in the Holton public school system. For a time, he also helped teach art in the schools.

In 1937, new crises led to major changes. On March 1, 1937, Zeke and Della’s homestead was again on the block at a sheriff’s auction held on the east steps of the Jackson County Courthouse. This time, the couple would not gain a reprieve as they had done five years earlier. Later in 1937, Zeke’s ongoing struggle with alcohol led to a brush with the law. Following an arrest on July 11, he pleaded guilty the next day to charges of being drunk in a public place and driving while intoxicated. He was fined $25 and sentenced to 30 days in the county jail.

What was unusual about the incident was the manner in which Barnes did his time. During most of his jail stay, he was occupied with the task of painting three murals in the Jackson County Courthouse. The timing suggests that the work may have been planned before his arrest, but dates of the news articles reporting progress on the murals indicate that most, and perhaps all, of the work was done while he was serving his sentence.

The murals were painted on the walls of the courtroom. One was placed behind the judge’s bench and depicted Lady Justice with her balance scales, a rendering that was, according to the Holton Recorder, “exceptionally well done.” The second was a seascape with angry, crashing waves, and the third, a landscape featuring a stream and pasture set against a background of darkening storm clouds. Lady Justice is now gone, remodeled out of sight. Both the seascape and the landscape remain visible as of 2008, although the space is no longer part of the courtroom proper.

In late 1937 or early 1938, Zeke and the family moved to Wichita, Kansas, ready for a fresh start in new surroundings. Della and Zeke ran a boarding house during their early years in Wichita, but what apparently prompted the move was the fact that Barnes landed a WPA-funded job working for the City of Wichita’s recreation department as its baseball program director. In April 1938, the recreation department inaugurated, under Barnes’ direction, a seven-week “baseball school” for junior high and high school boys. Zeke’s focus then shifted to promoting and organizing the summer’s youth league activities, including the American Legion junior league program and a city circuit that carried his name.

The baseball director post was not a long-term position for Barnes, and when it was over, it marked the end of any regular mention of him in the sports pages. There was the occasional exception, however, and a notable one occurred in the summer of 1944.

On June 25, 1944, nearly twenty years after their paths had crossed in that fateful Game 7, Zeke Barnes pitched, albeit briefly, opposite Walter Johnson at Lawrence Stadium in downtown Wichita. The event was the sixth annual showdown between the Knights of Columbus Shamrocks and the Midian Shrine Camels. In 1944, the game also served as a venue for selling war bonds. Johnson was a celebrity spokesman for the federal government in its war bond drive, and his appearance in Wichita had been arranged by Congressman Ed Rees for that purpose. The promotion involved opening the game with the two former major leaguers. The 56-year-old Johnson pitched an inning for each team, and the 47-year-old Barnes pitched an inning for the Camels. Johnson had the better outing, allowing only one run. Zeke, his arm long gone, was wild; he walked three, hit a batter, and left before the inning was over. Surely no one had expected much from the two Kansas veteran pitchers that sweltering afternoon. Still, with old memories stirred in a hotly competitive spirit, at some level it must have rankled just a bit to see his old rival steal the limelight once again.

During the 1940s and early 1950s, Barnes held a number of jobs, but none of them translated into a new career or even stable employment. He worked at several of the aircraft plants in the city—Beech, Culver, and Boeing—and he also tried his hand as a salesman. In late 1947 or early 1948, he opened a portrait studio on Douglas Avenue, but this, too, appears to have been short-lived. Early in 1948, the Associated Press reported an intriguing story that Ray “Hap” Dumont, the Wichita-based founder of the National Baseball Congress, had “made a deal” with Barnes to paint portraits of the baseball queens to be selected at each of the 24 district tournaments in Kansas that summer. It is not known, however, whether the project was actually implemented.

Throughout these years, Zeke continued to battle alcoholism. Not only was the illness a likely contributor to his employment difficulties, it severely strained his marriage and took a toll on the family. Finally, in 1948 or 1949, he and Della separated. The breach was serious enough to last three or four years, but it was not irrevocable. The couple reconciled in the early 1950s and remained together until his death. Barnes’ general health began to deteriorate during this time, and he suffered at least one major heart attack that limited his activities and took him out of the workforce for good.

He still dabbled in portrait painting, sometimes on a commission basis, sometimes as a hobby, and it clearly was a pleasurable diversion for him. One summer in the late 1940s or early 1950s, Zeke tagged along on a work trip with his son Jim and one of his nephews, both of whom had decided to join a wheat harvest crew. Because of Zeke’s health issues, the boys were concerned about leaving him alone in the motel room while they were out working. One day, when the crew was based in one of the larger cities in western Kansas, the boys went to check on him and found the room empty. Worried, they asked the motel clerk where he was. Zeke had left word that he had gone to the larger, fancier downtown hotel. They found him there, dressed in a new, nicely tailored suit, sitting in the lobby, engaged in his own enterprise of drawing quick portrait sketches of travelers arriving from the nearby train depot. He had done quite well at it, earning enough to upgrade his accommodations and to offer the boys a share of the spoils if they wanted to cut their harvest work short.

After Zeke and Della reconciled, they moved to a small house on the northwest outskirts of Wichita. Their home was not in a highly urbanized area, so Barnes decided to take on a new endeavor based on another longstanding interest. From his youth, Zeke had been an outdoorsman and especially loved hunting. So he, along with his son Jim, established a small kennel—which he named Zeke’s Hytail Kennel—for breeding and raising registered English Pointer dogs. The kennel was operational by 1955 and it became a satisfying pastime for Zeke during his final years.

In the early summer of 1958, the four Barnes brothers met at Zeke’s Wichita home for what proved to be their final reunion. Already the summer had brought sorrow. Jess had recently suffered a heart attack and just days after his release from the hospital, he and his wife Rebecca lost their El Dorado, Kansas, home to a massive tornado. But the summer’s worst blow for the Barnes family came on July 24, when Zeke himself was struck by a heart attack and died shortly after his admission to the Veterans Hospital in Wichita. He was 61 years old at the time of his death.

Barnes was returned to northeast Kansas for a memorial service and burial at the Holton Cemetery. A patriot to the end, he was laid to rest in military fashion, with the graveside portion of the service conducted by members of Holton’s American Legion Post 44. Five of the six pallbearers were comrades in arms from Company B who had gone to war with Zeke forty years earlier.

Some Barnes family members were a bit taken aback by the large crowd that gathered to mourn Zeke’s passing, not quite sure what had drawn so many strangers to the rites of farewell for a man who had not been part of the Holton community for two decades. But some life stories have the power to give pause and invite remembrance, regardless of the years that pass. And so it was with Zeke Barnes, the man who had lived bold and large in his prime, the small-town lad who had taken his game to New York and staked out his spot. So it was, too, with Zeke Barnes and his sadder tale, the man who had struggled to find his way when the world turned small again, stripped to the basics by economic hardship and clouded at times by a dependency he could not quite conquer. In the final years, Zeke capped his story with a certain sense of coming-to-terms, of righting the ship with Della and surrounding himself with the quiet pleasures found in his art, his dogs, and the bond of family. Through it all, he held title to those privileged places of his past, places that once traveled, are owned by the mind forever.

Notes About Sources

Major League Statistics. Unless otherwise noted, Major League Baseball is the source of major league pitching and hitting statistics. (See “Internet” section below for web site addresses.) Retrosheet.org was used for information about schedules, individual games, transactions, and team standings within the respective seasons. Baseballlibrary.com also was consulted for information related to team standings.

Minor League Statistics. Primary sources include the SABR Minor Leagues Database, The Sporting News, and Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. A partial record of Barnes’ minor league career was also reported by Baseball Magazine in an article published in September 1926. (See “One of the Four Brothers” citation in the “Articles” section below.)

Game Accounts. Newspaper articles were relied on for information about specific games. The New York Times was the primary source for accounts of New York Giants games and pennant races, although The Sporting News and other newspaper accounts were used as well. Retrosheet.org was consulted for information regarding starting pitchers and pitching outcomes, and for World Series game accounts. Information from Retrosheet.org, The Sporting News, and the New York Times was used to compile a database of Barnes’ pitching appearances by date, type of appearance (start/relief), opposing team, and outcome. The database was used to track his intra-season performances and intervals between game appearances.

Family History and Anecdotal Information. Special thanks are owed to Melany Barnes, Jan Achelpohl, Steve Achelpohl, Diana Kauffman, Vernon Barnes, Gary Barnes, Ilah Rose Askren, and Ruth Barnes Bemiller for the information they generously supplied about the history of the Barnes family. Much of the family history and anecdotal information was provided by them.

All Nations Team. Pete Gorton (head of the John Donaldson Network), Phil Dixon (baseball historian and author), and Kevin Anderson (archivist at the Casper College Western History Center), were especially helpful in efforts to establish Barnes’ involvement with J.L. Wilkinson’s World’s All Nations team.

Sources

Books

Alexander, Charles C. John McGraw. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995 (originally published in 1988).

Browning, Reed. Baseball’s Greatest Season, 1924. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Bruce, Janet. The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985.

Burk, Robert F. Much More Than a Game: Players, Owners, and American Baseball since 1921. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Chadwick, Bruce. When the Game Was Black and White: The Illustrated History of the Negro Leagues. New York: Abbeville Press, 1992.

Dittmar, Joseph J. “Teams Play Nine-Inning Game in 51 Minutes.” Baseball Records Registry: The Best and Worst Single-Day Performances and the Stories Behind Them, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co, 1997, 151-154.

Dixon, Phil with Patrick J. Hannigan. The Negro Baseball Leagues, 1867-1955: A Photographic History. Mattituck, NY: Amereon House, 1992.

Durso, Joseph. The Days of Mr. McGraw. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1969.

Ferrell, Robert H. America’s Deadliest Battle: Meuse-Argonne, 1918. Modern War Studies. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

———. Collapse at Meuse-Argonne: The Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2004.

Fowles, Brian Dexter. A Guard in Peace and War: The History of the Kansas National Guard, 1854-1987. Manhattan, KS: Sunflower University Press, 1989.

Graham, Frank. McGraw of the Giants: An Informal Biography. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1944.

———. New York Giants: An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 2002 (originally published in 1952).

Haterius, Carl E. Reminiscences of the 137th U.S. Infantry. Topeka, KS: Crane & Company, 1919.

Holway, John. Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. Westport, CT: Meckler Books, 1988.

———. The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History. Fern Park, FL: Hastings House Publishers, 2001.

Hoyt, Charles B. and Charles B. Lyon. Heroes of the Argonne: An Authentic History of the Thirty-fifth Division. Kansas City, MO: Franklin Hudson, 1919.

Hynd, Noel. The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract: The Classic – Completely Revised. New York: Free Press, 2001.

James, Bill and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff, ed. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball: The Official Record of Minor League Baseball –Third Edition. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 2007.

Lengel, Edward G. To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. New York: H. Holt, 2008.

McGraw, John. My Thirty Years in Baseball. New York: Arno Press, 1974 (originally published in 1923).

Metcalfe, Henry. A Game for All Races. New York: Metro Books, 2000.

Oxendine, Joseph B. American Indian Sports Heritage. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Podoll, Brian A. The Minor League Milwaukee Brewers, 1859-1952. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2003.

Ribowsky, Mark. A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884 to 1955. Secaucus, NJ.: Carol Pub. Group, 1995.

Sanford, Jay, and Mark Rucker. The Denver Post Tournament: A Chronicle of America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball Event. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2003.

Schlossberg, Dan. Baseball Gold: Mining Nuggets from Our National Pastime. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007.

Schott, Tom, and Nick Peters. The Giants Encyclopedia—Second Edition. Champaign, IL: Sports Publishing, 2003.

Sugar, Bert Randolph. Baseball’s 50 Greatest Games. New York: Exeter Books, 1986.

Thorn, John. Baseball’s 10 Greatest Games. New York: Four Winds Press, 1981.

Wallace, Joseph E. World Series: An Opinionated Chronicle: 100 Years. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 2003.

Wichita City Directory. Kansas City, MO: R.L. Polk and Company, 1939-43, 1947-49, 1952, 1957.

Young, William H. and Nathan B. Young, Jr. Your Kansas City and Mine. Kansas City, MO: Midwest Afro-American Genealogy Interest Coalition, 1997 (original published in 1950).

Articles

Allen, Lee. “Barnes Brothers Squared Off Ten Times in Major Careers.” The Sporting News, July 27, 1967.

Applebee, Charles A. “Jess Barnes Points to Days in Davenport as Happiest of His Career.” Davenport Democrat and Leader, October 23, 1925, 29-30.

“The Big League Barnes Boys.” The Literary Digest, June 27, 1925. (Based on an article by Cullen Cain that appeared in The Country Gentlemen. Also see “Scribbled by ScribeS,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1922.)

Bradley, Hugh. “That’s My Roomie.” Baseball Magazine, October 1937, 501. (Note: This article erroneously identifies Jess Barnes, rather than Virgil, as the one involved in the sprained ankle incident.)

Galbraith, Dan. “Ball-playing brothers return to northeast Kansas.” Holton Recorder, June 8, 1995.

Lewis, Allen. “This Was the Fastest Major League Game Ever.” Baseball Digest, August 1978.

Lieb, Frederick G. “When Brothers Win Fame on the Baseball Diamond.” Baseball Magazine, February 1923, 397-398.

Lightner, P.A. “Virgil Barnes, Former Giant, Portrait Artist.” The Sporting News, March 10, 1948.

“One of the Four Brothers (Comprising an Interview with Virgil Barnes).” Baseball Magazine, September 1926, 449-450.

“Members of the World’s Champion Giants stage an amateur concert in Texas…” (photo and caption). Baseball Magazine, May 1923, 535.

Snider, Dick. “Capitalizing on Sports.” Topeka Daily Capital, August 1, 1958.

“There Were Giants in the Earth in Those Days.” Holton Recorder, April 19, 1976, 1.

“The Talk of the Town: Profit.” The New Yorker, October 31, 1925.

Ward, John J. “A Unique Pitching Family: How the Four Barnes Brothers, Led by Jesse and Virgil, Aspire To Be Major League Pitchers.” Baseball Magazine, September 1924, 457 et al.

Newspapers

Alton Evening Telegraph (IL): March 26, October 22, 1924.

Amarillo Globe (TX): July 1, July 4, July 8, July 11, 1932.

Atchison Daily Globe (KS): June 4, 1917; September 4, 1949.

The Bee (Danville, VA): April 22, 1929.

Big Spring Daily Herald (TX): November 11, 1947.

Boston Daily Globe: October 26, 1921; April 5, 1922; March 10, October 11, 1924.

Bridgeport Telegram (CT): October 11, 1924; March 23, 1927.

Casper Daily Tribune (WY): July 18, July 23, July 25, July 27, July 28, July 30, 1917.

Charleston Gazette (WV): June 17, 1925.

Chicago Daily Tribune: April 25, 1923.

Daily Northwestern (Oshkosh, WI): February 21, March 7, March 11, March 13, 1929.

Decatur Evening Herald (Decatur, IL): March 23, 1927.

Denver Post: July 3, July 8, July 14, 1932.

Downs News and Times (KS): July 6, July 13, July 20, August 3, 1916.

Duluth News Tribune: September 21, 1921.

Eau Claire Leader (WI): August 26, 1922.

Evening State Journal and Lincoln Daily News (NE): November 22, 1919.

Farmers’ Vindicator (Valley Falls, KS): October 21, October 28, 1921.

Frankfort Daily Index (KS): October 16, 1916.

Glen Elder Sentinel (KS): July 6, July 27, 1916.

Goodland Republic (KS): July 21, 1916.

Hartford Courant: March 12, 1924; March 9, 1926.

Holton Recorder (KS): August 30, October 4, October 11, October 18, 1917; September 26, October 31, December 26, 1918; May 1, May 15, 1919; September 29, 1921; January 9, 1930; July 15, August 5, 1937; July 31, 1958.

Holton Signal (KS): July 2, September 3, 1914; June 24, September 23, October 14, 1915; July 20, 1916; August 9, August 30, September 6, October 25, 1917; January 9, 1930.

Horton Headlight-Commercial (KS): July 29, September 7, October 5, 1916; May 24, June 14, June 21, August 9, August 16, August 30, 1917; August 22, August 29, September 2, September 30, October 13, 1930.

Indiana Evening Gazette (PA): January 19, 1948.

Indianapolis Star: May 20, September 17, September 21, 1921.

Iowa City Press-Citizen: October 17, 1924.

Jackson County World (Circleville, KS): various dates, 1900-09.

Junction City Union (KS): July 1, July 2, July 5, 1932.

Kansas City Post: May 27, 1917.

Kansas City Star: June 8, 1919; September 17, 1921; August 5, 1926; April 7, 1929.

Kansas City Times: June 25, 1919; September 17, 1921; July 26, 1958.

Kingsport Times (TN): June 10, 1924.

Le Grand Reporter (IA): January 31, 1936.

Lima Daily News (OH): July 12, 1936; March 10, 1939; August 12, 1937.

Lincoln Daily Star (NE): June 29, July 14, 1917.

Logansport Press (IN): May 6, 1938.

Marysville (KS) Advocate-Democrat: September 24, 1914.

Morning Oregonian: November 21, 1919; June 26, 1921.

Nebraska State Journal: March 11, 1925.

Netawaka Chief (KS): June 29, July 6, September 7, 1916.

New York Times: numerous, 1919-28.

Norton Daily Telegram (KS): July 18, July 29, 1916.

Oshkosh Daily Northwestern: May 13, 1938.

Portsmouth Daily Times (OH): May 20, 1921.

Seneca Courier-Democrat (KS): September 3, 1914; June 8, July 20, August 10, 1916.

Seneca Tribune (KS): August 17, August 31, 1916.

Simpson News (KS): July 27, 1916.

Soldier Clipper (KS): August 19, 1914.

The Sporting News: May 20, October 7, December 9, 1920; February 24, 1921; March 23, March 30, May 11, 1922; May 3, June 7, August 16, 1923; April 3, May 15, October 16, 1924; June 25, 1925; June 17, 1926; March 22, 1928; March 14, 1929; April 11, 1929; July 23, 1936; March 10, 1948; July 22, 1967.

Syracuse Herald (NY): April 17, April 28, May 9, 1929.

Topeka Daily Capital (KS): June 10, June 13, September 10, 1917; May 9, 1919; October 24, 1921; October 21, 1922; October 3, 1924; December 13, 1928; March 14, 1929.

Topeka State Journal (KS): September 10, 1917.

Valley Center Index (KS): July 31, 1958.

Warren Tribune (PA): June 16, 1928.

Washington Post: numerous, 1919-28.

Weekly Kansas Chief (Troy, KS): September 28, 1916.

Wichita Beacon (KS): May 20, May 24, May 25, May 27, June 3, 1938; June 26, 1944; July 27, 1958.

Wichita Eagle (KS): March 27, April 2, April 3, April 5, May 10, May 12, September 11, September 12, 1938; June 26, 1944.

Internet

Baseball Almanac.

http://www.baseball-almanac.com/

Baseball Library.

http://www.baseballlibrary.com/

Baseball Reference.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/

Jaffe, Chris. “The 10 greatest Game Sevens in World Series history.” The Hardball Times, January 21, 2008.

http://www.hardballtimes.com/main/article/the-ten-greatest-game-sevens-in-world-series-history/

“John Wesley Donaldson,” home page of The Donaldson Network, directed by Peter Gorton, at:

http://johndonaldson.bravehost.com/

“Kansas Casualties in the World War, 1917-1919.” Compiled under Supervision of the Adjutant General of Kansas, Topeka, KS, 1921. Online transcription at:

http://skyways.lib.ks.us/genweb/archives/statewide/military/wwI/casualty/index.html

Kuenster, John. “Most dramatic Game 7: World Series finishes,” Baseball Digest, October 2004, at:

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FCI/is_10_63/ai_n6189423

“Letters Home from the War.” Online transcription of letters written by Lloyd Maywood Staley at:

http://www.u.arizona.edu/~rstaley/wwlettr1.htm

Major League Baseball—Giants History.

http://pressbox.mlb.com/pressbox/downloads/y2006/sfg/history.pdf

Major League Baseball—Historical Player Stats.

http://mlb.mlb.com/stats/historical/player_stats.jsp

Major League Baseball—Historical Team Stats.

http://mlb.mlb.com/stats/historical/team_stats.jsp?c_id=mlb

“The Personal Diary of William J. ‘Bill’ Schira in World War I.” Transcription online at:

http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/memoir/Schira/Schira.htm

RetroSheet, Inc.

Shin, Don. “This Week in Giants Baseball History, Sept. 19-25,” SFHardball.com.

http://sfgiants.scout.com/2/440922.html

Singer, Tom. “Stage set for coming attractions,” July 11, 2007, mlb.com.

http://www.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20070708&content_id=2075104&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb

SI Vault: Baseball’s Best Game 7s.

http://vault.sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/gallery/featured/GAL1000170/14/14/index.htm

SABR Minor Leagues Database

http://www.minors.sabrwebs.com/cgi-bin/index.php

Government Documents and Records

Certificate of Death—Virgil J. Barnes. State of Kansas, 1958.

Enlistment Record – Virgil J. Barnes. On file in the Kansas Adjutant General archives, Kansas State Historical Society.

“History of the 137th Infantry: Regimental History Series.” Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Project of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Kansas, Sponsored by the Adjutant General of Kansas, Topeka, KS, 1942.

Honorable Discharge from the United States Army – Virgil J. Barnes. On file in the Kansas Adjutant General archives, Kansas State Historical Society.

Initial Muster Rolls – Kansas National Guard 1917. Initial Draft Roll of Company B of the Second Kansas Infantry, Army of the United States, from the 5th day of August, 1917 to the 14th day of August, 1917. Records of the Kansas Adjutant General, on file at the Kansas State Historical Society.

Jackson County (KS) Superintendent of Public Instruction. Scholastic Census Records for District 16, 1911-1913. On file at the Kansas State Historical Society.

Kansas State Census, 1905.

Land transaction records on file at the Jackson County Register of Deeds, Holton, Kansas.

Record of Prisoner Board-Book 2, Sheriff’s Office, Jackson County, Kansas.

United States Bureau of the Census. United States Census: 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930.

Interviews, Family Recollections, Genealogical Materials

Achelpohl, Jan (granddaughter of Virgil Barnes). Telephone interviews, April 2007 and subsequent dates.

Achelpohl, Steve (grandson of Virgil Barnes). E-mail communication and telephone interview, Spring 2007.

Askren, Ilah Rose (grandniece of Luther Barnes). Interview, June 2007.

Barnes, Melany (granddaughter of Virgil Barnes). Interview and e-mail communications, various dates, 2007, 2008.

Barnes, Vernon (grandnephew of Luther Barnes). “Descendants of Luther C. Barnes,” and other genealogical materials. E-mail communications, various dates, 2007, 2008.

Kauffman, Diana (niece of Virgil Barnes). E-mail communications, April 2007 and subsequent dates.

Merli, Bette R. (grandniece of Sade Barnes). Collection of genealogical materials and clippings compiled circa 1985-1986; on file with the Jackson County (KS) Historical Society.

Other

Contract Cards—Virgil J. Barnes, Jesse Barnes, Charles Barnes, and Clark Barnes. National Baseball Hall of Fame, Giamatti Research Center.

Gorton, Pete. “1917 Games [of the All Nations team],” internal working document, and subsequent e-mail communications.

Player file—Virgil J. Barnes. National Baseball Hall of Fame, Giamatti Research Center.

Notes

1 “One of the Four Brothers (Comprising an Interview with Virgil Barnes),” Baseball Magazine, September 1926, 450.

2 Many contemporary articles used Barnes’ given name of Virgil, but “Zeke” appeared frequently as well. Because he apparently preferred to be called by his nickname (see “Braves Again Bow to the Giants, 8-4,” New York Times, April 24, 1925, 13), “Zeke” is used throughout this biography. The origin of his nickname is not known.

3 “One of the Four Brothers,” 450.

4 Ibid.

5 William H. Young and Nathan B. Young, Jr., Your Kansas City and Mine, “The Story of the Kansas City Monarchs,” Midwest Afro-American Genealogy Interest Coalition (reprint of 1952 publication), Kansas City, MO, 1997, 69. Also, “Sporting Comment,” Kansas City Star, August 5, 1926, 18.

6 Adjutant General of the State of Kansas, Initial Draft Roll of Company B of the Second Kansas Infantry, Army of the United States, from the 5th day of August, 1917 to the 14th day of August, 1917, Initial Muster Rolls – Kansas National Guard, 1917, on file at the Kansas State Historical Society.

7 Robert H. Ferrell, America’s Deadliest Battle: Meuse-Argonne, 1918, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2007. In 47 days of fighting at Meuse-Argonne, over 1.2 million Americans took part, and 26,000 lost their lives. Nearly 100,000 were injured.

8 Slang referring to a small, cheap, old automobile.

9 “One of the Four Brothers,” 449.

10 Robert Ferrell, Collapse at Meuse-Argonne, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004, 85.

11 “One of the Four Brothers,” 449.

12 It is not known for certain whether Barnes exchanged his wound chevron for a Purple Heart. However, the military headstone which marks his grave includes the abbreviation “PH,” thought to be a designation for Purple Heart recipients.

13 The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball lists Baltimore’s Jack Ogden as the International League’s 1920 strikeout leader, with 137. The “1920 Pitching Records of the International League” which appears in the December 9, 1920 issue of The Sporting News reports Ogden with 137 strikeouts, but also reports that Barnes had 142. The 1926 recap of Barnes’ career which appears in Baseball Magazine’s “One of the Four Brothers” also credits him with 142 strikeouts in 1920. Finally, Baseball Reference cites Barnes as the league leader in both losses and strikeouts. See: http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Rochester_Hustlers.

14 “One of the Four Brothers,” 450.

15 “One of the Four Brothers,” 449.

16 Dan Schlossberg, Baseball Gold: Mining Nuggets from Our National Pastime, Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007, 264.

17 “Yanks Rout Giants in Fifth Game, 8-1,” New York Times, October 15, 1923, 1.

18 Heywood Broun, “It Seems to Me,” Boston Daily Globe, October 19, 1923, 18.

19 Lee Allen, “Barnes Brothers Squared Off Ten Times in Major Careers,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1967, 7. Also see: Tom Singer, “Stage set for coming attractions,” July 11, 2007, mlb.com, http://www.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20070708&content_id=2075104&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb (note: the Barnes brothers faced each for the first time on June 26, 1924, rather than May 3,1927, as indicated in a table in this posting).

20 “Barnes’s Pitching Stops Pirates, 3-1,” New York Times, August 2, 1924, Sports Section, 6.

21 Don Shin, “This Week in Giants Baseball History, Sept. 19-25,” SFHardball.com, http://sfgiants.scout.com/2/440922.html. Barnes’ record of 371 at bats without an extra base hit was broken on September 20, 1993 by Jim Deshaies.

22 Joe Vila, “Giants Have Little Standing With Fans,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1924, 1.

23 Ibid.

24 Rogers Hornsby, “Barnes is Star of McGraw Hurlers, Who Excel Only in Quantity, Hornsby Asserts,” Topeka Daily Capital, October 3, 1924, 10.

25 Joseph Wallace, World Series-100 Years: An Opinionated Chronicle, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003, 59.

26 Frederick G. Lieb, “Washington’s Victory on Par With Great Red Sox-Giant Tussle at Boston in 1912,” Bridgeport Telegram, October 11, 1924, 3.

27 John Kuenster, “Most dramatic Game 7: World Series finishes,” Baseball Digest, October 2004, as reproduced at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FCI/is_10_63/ai_n6189423.

28 Grantland Rice, “Senators Win World Championship, 4-3,” Boston Daily Globe, October 11, 1924, 5A.

29 “The Johnson of Old Too Much for Giants,” New York Times, October 11, 1924, Sports, 9.

30 “Barnes Best Say Nats,” Iowa City Press-Citizen, October 17, 1924, 11.

31 Bill Snypp, “Snypp’s Sports Snacks,” Lima News, March 10, 1939, 18.

32 Allen, “Barnes Brothers Squared Off Ten Times in Major Careers.”

33 “Dizzy Dean Lost to Cubs Four Weeks With Sore Arm,” AP, Logansport Press (IN), May 6, 1938, 6.

34 “Virgil Barnes Predicts ‘Dizzy’ Dean on Way Out,” United Press, Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, May 13, 1938, 19. Note: After the 1938 season, Dizzy Dean won only nine more games in his major league career.

Full Name

Virgil Jennings Barnes

Born

March 5, 1897 at Ontario, KS (USA)

Died

July 24, 1958 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.