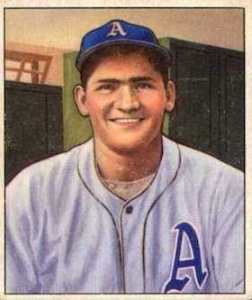

Alex Kellner

In 1949 left-handed hurler Alexander Raymond Kellner joined his namesake, Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander, among others with a 20-win campaign in his freshman season. The next year Kellner joined a smaller community, losing 20 games in his sophomore year. Through 2015, only 15 pitchers (11 from the 19th century) have won 20 games as a rookie, only to lose 20 the next year. Kellner is the last to do so. In 1951 this unlucky southpaw became the third pitcher to lead the American League in losses two consecutive years.

In 1949 left-handed hurler Alexander Raymond Kellner joined his namesake, Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander, among others with a 20-win campaign in his freshman season. The next year Kellner joined a smaller community, losing 20 games in his sophomore year. Through 2015, only 15 pitchers (11 from the 19th century) have won 20 games as a rookie, only to lose 20 the next year. Kellner is the last to do so. In 1951 this unlucky southpaw became the third pitcher to lead the American League in losses two consecutive years.

These attributes imply a hapless and incompetent career. Instead, they spoke to the woeful Philadelphia (later Kansas City) Athletics in the 1940s and 1950s. Throughout much of Kellner’s 12-year career he was often the mound mainstay for the inept franchise. The club’s Opening Day starter in 1955, Kellner made history by throwing the first American League pitch in Kansas City, Missouri.

Alex Kellner was born on August 26, 1924, the second of three sons (four children) of John Justus and Julietta (Garcia) Kellner, in Tucson, Arizona. A veteran of World War I, John carved a long career as a cattle rancher and newspaper stenographer. He had once possessed an earlier aptitude: In the 1920s John pitched in the Copper State League1 and tossed a no-hitter in Tucson’s Randolph Park (later Hi Corbett Field), the very field on which Alex began his professional career in 1941. John’s passion for baseball was evidenced by the names he gave his second and third sons, honoring “Old Pete” and Walter Johnson, respectively. He started instructing 4-year-old Alex, later training him by throwing tennis balls through a drain pipe.

The tutelage took for Alex (as it did for younger brother Walt, who followed Alex into the major leagues; their older brother, John Jr., found success in high school football). The siblings attended Tucson’s Amphitheatre High School where Alex gained acclaim for firing four no-hitters. In 1941, Cincinnati Reds scout Mickey Shader signed the 16-year-old. A former minor league player and manager, Shader served as president of the Class C Tucson Cowboys in the Arizona-Texas League. He assigned Kellner to the Cowboys and, in his professional debut before a hometown crowd of 2,500, the youngster prevailed in a 7-6 win. “I had a fair season,” Kellner later recalled. “14 and 5, but was wild.”2

After graduation from high school in 1942 Kellner was ticketed for Ogden, Utah in the Pioneer League but illness delayed his report. When fully recovered, he was sent instead to the Muskogee (Oklahoma) Reds in the Western Association. By far the club’s youngest player, the 17-year-old placed among the team leaders with 11 wins despite continued wildness (a constant throughout Kellner’s career). When the season ended Kellner returned home elated over a promotion to Class-A Birmingham in 1943. Five years and a franchise switch elapsed before Kellner made his next professional appearance.

On April 1, 1943, Kellner enlisted in the US Navy. He served in the South Pacific on the USS Callaghan until December 1944. Seven months later it became the fleet’s last destroyer sunk in World War II; a kamikaze attack off Okinawa that killed or wounded 120. Kellner’s service was not devoid of baseball, playing for military base teams in San Diego, California, and Norfolk, Virginia. Discharged on May 4, 1946, Kellner, citing exhaustion, refused to report to the Reds’ minor leagues. Despite farm director Frank Lane’s protestations, general manager Warren Giles released the lefty. Kellner returned to Tucson and pitched in semi-pro leagues.

He resurfaced in the Philadelphia Athletics’ organization in 1947, signed by scout Tink Turner. A former pitcher who made one major league appearance in 1915, Turner was the owner of the Athletics’ Portland affiliate in the 1920s-1930s. It is unclear where Turner discovered Kellner (in 1949 he also signed Walt Kellner). One theory is that they crossed paths during Kellner’s military service. (Turner signed pitcher Fred Heimach after discovering him in France during World War I.) Kellner was assigned to Birmingham – Philadelphia’s newly affiliated Southern Association club – where he placed among the team leaders with 11 wins. An unimpressive 4.96 ERA was countered by a strong strikeout yield that earned the hard-throwing lefthander an invitation to the A’s training camp in West Palm Beach, Florida, the following spring.

In 1947 the Athletics finished 78-76 for their first winning season in 14 years. The Athletics achieved this relative success despite only one southpaw on the staff: Lou Brissie, who made just one appearance. Owner-manager Connie Mack, looking to provide more balance, took an instant liking to Kellner. Originally slated for another minor league season, Kellner was placed instead on the parent team’s roster.

Kellner made his major league debut on April 29, 1948, against the Boston Red Sox. Entering with a 4-0 deficit in the second inning Kellner sandwiched a strikeout of pitcher Earl Johnson around two pop-fly outs. Kellner’s capable debut (3 runs surrendered in six innings) garnered a second (though much shorter) stint against the Cleveland Indians five days later. A logjam surfaced when the Athletics purchased veteran righty Nels Potter from the St. Louis Browns on May 15. Kellner was optioned to the Class-A Savannah Indians in the South Atlantic League. Seemingly a demotion from prior Class-AA play, Kellner’s placement was precipitated by the rash of injuries suffered by the Indians’ staff. Connie Mack ensured that the youngster would not suffer lesser pay as a result of the assignment. Kellner, in turn, had nothing but praise for the organization: “I learned more about pitching in my brief stay [in Philadelphia] than in all my previous years in baseball.”3

On May 21 Kellner made his Savannah debut with an 8-2 win over the Columbus Cardinals (an eighth-inning line drive off his ankle the only barrier to a complete game). Six weeks later he tossed the league’s only 1948 no-hitter, a 10-strikeout performance against the Macon Peaches in which only three batters hit the ball out of the infield. This 1-0 win was one of six straight victories that prompted a recall to Philadelphia. A promising return against the Washington Senators on August 10 (two innings of no-hit relief) yielded to a 15.43 ERA over his next nine appearances, including his first major-league start in which Kellner did not survive the first inning. A more encouraging appearance against the New York Yankees on September 30 lowered Kellner’s ERA to a season-ending 7.83.

Despite these challenges Mack remained a fervent supporter of the southpaw. When veteran hurler Phil Marchildon and righty Bill McCahan struggled out of the gate in 1949, the timeworn skipper turned to Kellner. The youngster got his second career start on April 26 in Yankee Stadium. After the Bronx Bombers touched him for three runs in the second, Kellner settled down to surrender just one hit over the next five innings. The Athletics battled back to take a 4-3 lead when, in the eighth, Kellner yielded a two-run homer to suffer a loss in his first major league decision. His first win came five days later in a less effective outing against the Senators. A brutal start in Chicago on May 8 relegated Kellner to the bullpen where he garnered three wins in four days (May 14-17). He returned to the rotation to collect two complete game victories. A six-game streak beginning June 8 hoisted Kellner to 12-3 and earned him an All-Star berth (he did not make an appearance in the July 12 slugfest).

Kellner suffered six losses in eight decisions before closing out the campaign 4-1 in his final six appearances. A complete-game victory over the Senators on October 1 accounted for Kellner’s 20th win – the first Athletics’ hurler since Hall of Famer Lefty Grove in 1933 to reach the 20-win plateau. Kellner garnered consideration in Most Valuable Player and Rookie of the Year award voting (he was runner-up to Roy Sievers in the latter) while placing among the American League leaders in wins,4 innings pitched (245) and complete games (19).5 Kellner credited his success to improved control achieved by continued usage: “Sitting around kills me … Resting makes me strong, and getting strong makes me wild. I have to be more relaxed to have control.”6

Philadelphia finished the 1949 season 81-73. This relative success was attained largely on the back on the club’s young hurlers, a staff that attracted considerable attention on the trade circuit. The Athletics’ confidence was bolstered by the October 28 signing of University of Arizona’s hard-throwing hurler – and Kellner’s brother – Walt. Meanwhile, Kellner was feted with the celebrity status accorded a 20-game winner, serving as the guest of honor at the January 24, 1950, Phoenix Press Box Association banquet. He also earned a sizeable raise from the Athletics before embarking on a fishing trip to Mexico.

In February 1950 the brothers drove from Tucson to Philadelphia to accompany the team on its trek to Florida. Kellner scoffed at the notion of a sophomore jinx, boldly predicting another 20-win season while expressing confidence in his brother’s professional debut. These resolute assurances proved infectious when a club official projected pennant aspirations for the coming season. As events developed, not a one of these forecasts proved true: Walt struggled mightily with the Lincoln (Nebraska) A’s, placing among the Western League (Class-A) leaders with 14 losses. Kellner and the Athletics in general fared little better.

Kellner’s challenges began in spring training, including a March 30 roughing-up at the hands of the A’s Class-AAA affiliate. Management’s concerns about the lefty’s readiness were manifested by Kellner’s season debut from the bullpen. His first start came on April 22, a 15-inning complete-game win over the Red Sox. Three weeks later an extra-inning complete-game loss to the Cleveland Indians lowered Kellner’s record to 2-2 despite a strong 3.14 ERA. This was his season’s high-water mark as Kellner went 6-18, 6.02 over his next 31 appearances (25 starts). He surrendered career highs of 253 hits, 28 homers, and a league-leading 137 earned runs. In his last appearance Kellner tied Chicago Cubs righty Bob Rush for most major league losses while becoming the only sophomore pitcher since 1920 to lose 20 games following a 20-win rookie season.

Kellner had plenty of company as the Athletics suffered a miserable 1950 campaign. The young, highly-lauded staff disintegrated to a major-league worst 5.49 ERA. The club’s offense was nearly as bad – second fewest runs scored in the American League – as Connie Mack, in his last season as manager, suffered a 102-loss campaign. In January 1951, newly-appointed skipper Jimmy Dykes admitted, “No club could look as bad as we did last season.” Citing Kellner among his talented corps, Dykes added, “We had a good club and have a nucleus of a good one now.”7

Despite the 20-loss campaign, interest in Kellner remained high. In December the Yankees declined an offer of the lefty when the Athletics’ asking price was deemed too steep. Determined to reverse his fortunes, Kellner captured the club’s first complete game in 1951 Grapefruit League play. A slight setback – a pulled thigh muscle sustained during first base coverage drills – did not derail his spring as Kellner opened with a four-hit, complete-game victory against the Red Sox in Fenway Park on April 20.8 “No club looks too good when it runs into the kind of pitching we got from Kellner,”9 chirped Dykes.

But much like the preceding season, Kellner started a May slide that yielded similarly dire results: 4-12, 5.73 in 21 appearances (17 starts) beginning May 18. The tumble was halted on August 29 by Kellner’s first career shutout, a five-hitter against the Indians in Cleveland Stadium. A strong close – 3-1, 3.05 in five starts including a heartbreaking loss to the Yankees on September 3 – spared further grief. He finished the season tied for the league lead in both losses (14) and wild pitches (9). Despite the season’s challenges, Kellner still placed among the club leaders for the feeble Athletics. His accomplishments were acknowledged by an invitation to tour the south with a barnstorming American League All-Star squad that fall, returning to his Tucson home in November.

Kellner began the 1952 season in his typically strong fashion. Through June 8, excluding two miserable starts against the Indians, he possessed a 1.89 ERA over nine starts – a mark deserving more than his 5-3 record.10 Kellner twirled two shutouts against the Browns and missed two more after ninth-inning tallies by the Chicago White Sox (May 3) and Detroit Tigers (June 3). An effective right-handed batsman,11 on June 8 Kellner helped his cause with three hits and three RBIs, including his first major league homer against Cleveland reliever Mickey Harris, in an 11-3 romp over future Hall of Famer Bob Feller.

In June, in equally typical fashion, Kellner began struggling. A yield of 32 runs over five starts yielded four losses and drove his ERA above five. Kellner righted himself to win seven of 10 to finish 12-14, 4.36 in 34 appearances (one in relief). Despite surrendering a major-league high 112 earned runs, Kellner once again placed among his team’s leaders in a variety of categories.

Though the Athletics finished 79-75, they were one of the hottest teams in July and August. In December, anticipating the emergence of Kellner’s brother among the ranks of the league’s youngest staff, general manager Art Ehlers predicted a pennant run: “In Bobby Shantz, Harry Byrd and Alex Kellner … we have three of the best … three top-flighters.”12 As Kellner busied himself during the offseason digging a cistern and building an addition to his Tucson home, the Phoenix Press Box Association nominated him as the state’s professional athlete of the year.

But when spring arrived Kellner appeared anything but top-flight. In a March 9, 1953, exhibition against the Pittsburgh Pirates in Havana, Cuba, the late-signing lefty surrendered six runs in the first inning of a 9-7 loss, while a 9.00 ERA into April caused the Athletics to begin shopping Kellner. It thus came as a surprise when he received the April 14 opening day nod over Shantz, the reigning American League MVP, in New York. Dykes explained that he wanted a southpaw but was reluctant to subject the high-strung Shantz to the nerve-wracking rigors of an opening assignment in Yankee Stadium. The maneuver proved providential when Kellner’s five-hit shutout handed the Bronx Bombers their first inaugural loss in six years (it was also the Athletics’ first opening day win in five years). The opening day blanking was the Yankees’ first since 1936. Five days later Kellner bested this effort with a two-hit shutout of the Bombers in Philadelphia.13 Interestingly, outfielder Gene Woodling, a player often benched against southpaws, delivered the two hits.

On April 24, Kellner’s scoreless string continued another 3 2/3 innings until the Red Sox reached him in the fourth. The 7-2 win in Fenway Park was followed by an agonizing 2-1 loss to the Indians on April 29. The Phoenix PBA named him Arizona athlete of the month as Kellner concluded April at 3-1, 1.03. The lefty surrendered just two walks in four starts. Crediting veteran Ray Murray, who received the bulk of catching duties for the only time in his six-year career, Kellner yielded only 51 walks for the season – his lowest while pitching over 133 innings.14

The general manager’s pennant hopes proved laughable in light of the team’s 95-loss season. Despite solid pitching Kellner fared little better: 11-12. Lack of run support cost him dearly as Kellner suffered seven losses and one no decision despite an even more impressive 3.44 ERA. In July teammates and scribes were outraged when Kellner was bypassed for an All-Star selection, Yankee manager Casey Stengel selecting two of his own instead. Kellner’s only struggles surfaced in August following time lost to shoulder bursitis. His season was completely shut down after August 26 when he sustained a fractured finger. Despite the early exit Kellner placed among the league leaders in complete games (14) and – on a lesser note – led the circuit with 10 wild pitches.

Much as they would throughout the remainder of his career, injuries and illness spelled much of Kellner’s 1954 season. A strong Grapefruit League campaign launched Kellner’s commonplace strong start, including an April 20 shutout against the Senators in which he came within four outs of a no-hitter. Eleven days later Kellner registered another solid performance: a 10-inning complete game victory over the Baltimore Orioles in which he did not surrender an earned run.

But a stomach ailment on April 25 forced the lefty to an early shower against the Yankees. Two months later Kellner missed a start after contracting pleurisy; shortly after he pulled his back in a win over the Red Sox. But the most significant occurrence came against the Senators on May 29 when Kellner suffered a strained elbow ligament. He chose to adjust his delivery and pitch through the pain, a decision that cost him dearly. By September he developed an ailing shoulder that disturbed his ability to sleep. Meanwhile his performance suffered greatly: Until shut down on August 28, Kellner struggled at 1-9, 9.80.

Despite the physical challenges the lefty remained the ace of the franchise. When the team moved to Kansas City in 1955 Kellner, exhibiting restored health in spring training, was granted the honor of pitching the home opener. A crowd of 150,000 lined the downtown streets for a pregame parade before former President Harry Truman threw out the first ceremonial pitch. Kellner held the Tigers in check for the first three innings in leading the relocated club to their historic first win. Kellner’s reward: the discovery that his car had been towed from a no-parking zone.

Two weeks later Kellner earned Kansas City’s first shutout with an April 24 win over the White Sox. A bout of flu caused him to miss his next start, while back spasms caused Kellner’s early exit against the Orioles on May 11. Six days later he rebounded with a shutout over the Senators and tossed a one-hit whitewash against the Orioles on June 26. But not all went swimmingly. Prior to the one-hitter Kellner suffered five straight losses. He yielded a 475-foot blast to Mickey Mantle in Yankee Stadium on June 21, followed a month later by the first mammoth drive to clear the center field fence in KC’s Municipal Stadium (the latter shot by pinch-hitter Bob Cerv was the first of two consecutive pinch-hit homers, a league first). Back spasms caused another early exit on July 26 in a 3-1 win over the Senators. Kellner won five of his last six decisions to finish 11-8, 4.20.

In October the White Sox pursued Kellner in a proposed six-player swap that never happened. The following spring, evidencing no lingering back problems, Kellner’s produced a successful exhibition campaign. He earned his last opening day assignment, a 2-1 win over the Tigers on April 17, 1956, wherein the only run surrendered was an inside-the-park homer by the opposing pitcher. Kellner suffered a tendon pull in his left elbow that limited him to just one appearance in May. Resulting arm stiffness limited him to one appearance after August 21. Held under 100 innings for the first time since his debut campaign, Kellner finished 7-4, 4.32. Despite the injuries Kellner attracted interest from the Red Sox but nothing came of this.

Kellner twirled a 2.04 ERA in his first five appearances of 1957 but could not muster a win. The Athletics’ anemic offense – last in the majors in runs scored – proved an insurmountable challenge. On May 16 he came to the plate against Yankees’ righthander Bob Turley after two consecutive walks (the equivalent of an Athletics’ rally) and popped up a sacrifice bunt, earning Kellner the dubious distinction of hitting into the majors’ first triple play of the season. Herculean efforts were required to capture a victory. He finished 6-5, 4.27, five of the wins secured when Kellner surrendered less than three runs.

Entering 1958 Kellner was one of only three Athletics remaining from the 1954 Philadelphia squad.15 But a miserable start, combined with the team’s desire to promote youngster Bud Daley from Class-AAA Buffalo, resulted in Kellner’s sale to the franchise that originally signed him 17 years earlier, the Cincinnati Reds.16 Evidenced by future Hall of Famer Yogi Berra’s quotes four years earlier, the lefty would not be missed: “If Alex Kellner would like to move to the National League, I would give him a basket of fruit or something. That guy’s left-handed motion gives me the heeby-jeebies.”1718

In three of his final four appearances with Kansas City Kellner showed signs of turning his season around: 2.51 ERA over 14 1/3 innings. The premature sale accrued to the Reds’ benefit. As veteran righty Brooks Lawrence struggled in the second half of 1958 the club turned increasingly to Kellner. Excluding two difficult August outings against the Pittsburgh Pirates, Kellner finished strong over the final three months (7-2, 1.37 in 14 appearances). It thus came as a surprise when, five days after the season, Kellner was sent to the St. Louis Cardinals in a six-player deal. Injury may explain the sudden departure. The 34-year-old was used sparingly over the last six weeks of the season and general manager Gabe Paul “felt Kellner ha[d] seen his best days.”19

A leg injury in the Cardinals’ spring camp delayed Kellner’s Grapefruit League debut until March 21, 1959. But this appearance — three innings of one-hit relief — propelled Kellner to his usual early success. On April 30 he dueled with future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn, surrendering a fourth-inning homer to Hank Aaron in a 1-0 loss to the Milwaukee Braves. Two weeks later Kellner’s 2.49 ERA attracted trade queries from the San Francisco Giants. In another start against the Braves June 10 he earned his second win of the season. It turned out to be his last. Beset by elbow pain, Kellner made a start in Milwaukee on June 23 and did not survive the first inning. He was assigned to the disabled list and never returned.

In the offseason the Cardinals unsuccessfully shopped Kellner. He was released in January. Throughout 1960 Kellner tried to garner interest from other teams. That winter he submitted his retirement papers. Following a brilliant rookie campaign, Kellner finished a 12-year career 101-112, 4.41 (April-May: 3.58) in 321 career appearances.

In 1949 Kellner was asked if he had any children. “Gosh,” he replied. “You embarrass me … I am not married … I want to get myself settled in baseball, earning a good salary, before ever giving any consideration to double harness.”20 But Kellner never married. He returned to Tucson and found employment in construction until arthritis and other health concerns forced his retirement in the mid-1970s. He ballooned to 284 pounds and was bound to a cane to walk.

Before the crippling disease, Kellner was an ardent fisherman and hunter. He and his brother shared the unique hobby of capturing mountain lions and bears for zoos and circuses. Kellner also kept a steady pulse on baseball and in his later years showed a preference for watching collegiate play over major league ball. Interviewed by Norman Macht for the author’s trilogy of Connie Mack, Kellner proudly displayed his golden anniversary 1950 Athletics’ uniform. In 1990 he earned induction into the Puma County [Arizona] Sports Hall of Fame. Six years later, on May 3, 1996, Kellner passed away in Tucson. He was 71 years old. Kellner died in his sleep on the property he’d bought many years earlier with his signing bonus.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR members Rod Nelson, Chair of the SABR Scouts Committee, and Norman Macht.

Sources

Ancestry.com

tucsoncitizen.com/morgue/2006/06/21/16588-corky-kellner-was-one-of-city-s-all-time-best/

pcshf.org/bios/kellneralex.php

destroyerhistory.org/fletcherclass/usscallaghan/

baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/kellner_alex.htm

baseball-reference.com/blog/archives/9814

tucson.com/news/blogs/morgue-tales/tucson-notable-major-league-pitcher-alex-kellner/article_b87c9848-1f5c-11e5-83b5-5f6cb5986190.html

books.google.com/books?id=PIjeCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA186&lpg=PA186&dq=alex+kellner+baseball&source=bl&ots=S239sl7ALd&sig=YElmmBO3mOEJjfSBCRK1wx_-U7A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CEYQ6AEwCDgUahUKEwjinsLO1uDGAhXOG5IKHV2xBwU#v=onepage&q=alex%20kellner%20baseball&f=false

Notes

1 Another source indicates he played in the Arizona-Texas League.

2 “Cactus Kellner Proves Thorn for Hitters,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1949: 4.

3 “A’s Route-Going Hurlers Setting Endurance Pace for Other Major Staffs,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1958, 10.

4 Kellner had a perfect 7-0 record against the lowly St. Louis Browns.

5 On a lesser note, Kellner also placed in yield of 18 homers, 129 walks, 243 hits and seven wild pitches.

6 “Cactus Kellner Proves Thorn for Hitters.”

7 “Rickey Describes ‘Luck’ as By-Product of Planning,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1951, 15.

8 The victory marked the Athletics’ first win in Fenway in two years.

9 “Kellner Kayoes Red Sox, But Dykes Still Picks ‘Em,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1951, 19.

10 Often lacking run support, half of Kellner’s 12 wins in 1952 were by a one-run margin; in 10 of his 14 losses the Athletics scored fewer than four runs.

11 In his career Kellner was used twice as a pinch-hitter. He was particularly effective against left-handers: .268-3-11 in 157 ABs. Through 2015, Kellner’s eight-game hitting streak (9/8/49-5/11/50) remains one of the longest for a pitcher.

12 “Art Ehlers’ Christmas Forecast – Flag in ’53,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1952, 19.

13 On May 31 Kellner failed in his attempt to become the first since Walter Johnson in 1908 to twirl three consecutive shutouts against the Yankees.

14 A surprising low number considering Kellner was experimenting with a knuckleball. There was also evidence of his venturing with a spitball.

15 Kellner was the only athlete to play for every Athletics manager through 1958.

16 Reds’ then-coach Jimmy Dykes, Kellner’s manager in Philadelphia from 1951-1953, likely influenced this acquisition.

17 “Toughest Hitter? Toughest Pitcher?” The Sporting News, December 8, 1954, 4.

18 Joe DiMaggio had similar problems with Kellner: .150-1-6 in 49 plate appearances.

19 “Redlegs ‘Gambling’ on Ennis’ Return to Old Slugging Form,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1958, 12.

20 “Cactus Kellner Proves Thorn for Hitters.”

Full Name

Alexander Raymond Kellner

Born

August 26, 1924 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

Died

May 3, 1996 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.