Bones Ely

Fred “Bones” Ely did not become an everyday starter in the major leagues until he was 30 years old, but then he spent nearly a decade as one of the game’s top defensive shortstops. He gained lasting fame, however, for losing his job with the Pittsburgh Pirates to one of the greatest players in baseball history.

Fred “Bones” Ely did not become an everyday starter in the major leagues until he was 30 years old, but then he spent nearly a decade as one of the game’s top defensive shortstops. He gained lasting fame, however, for losing his job with the Pittsburgh Pirates to one of the greatest players in baseball history.

The circumstances of Ely’s replacement as the Pirates’ shortstop by Honus Wagner in 1901 were controversial. During the war between the National League and the American League at the turn of the 20th century, Ely was accused of being a spy for the upstart AL and encouraging other players to jump to the Junior Circuit. The Pirates released Ely when they found out about his subterfuge and moved Wagner from right field to shortstop. Pittsburgh fans booed him at first1 but were quickly won over when Wagner proved to be even better at the position than the popular veteran.

Years earlier, Ely had been a versatile two-way player, a pitcher and outfielder who always seemed to find himself at the edge of trouble — if not in the center of it. He played on several integrated teams in the minor leagues, but may have played an indirect role in the International League’s setting of the color line in 1887. Ely was also an early investor in the Pacific Coast League as it fought to establish itself in Organized Baseball. He bounced around with 15 teams in a 19-season professional career, never staying in one place for long, but leaving a memorable impression everywhere he went.

William Frederick Ely was born June 7, 1863, in North Girard, Pennsylvania, on the shores of Lake Erie near the Ohio border. A month later, on the other side of the state, the Battle of Gettysburg would captivate the attention of a divided nation. Fred’s well-to-do family was mostly insulated from the Civil War; his father, Benjamin, a druggist, was a native of Otsego County, New York, and a graduate of the Medical College of Castleton, Vermont.2 His mother, Elizabeth (Caryl) Ely, who could trace her ancestors back to the Mayflower3, raised Fred and his seven siblings and sent the boys to school at Girard Academy, where they learned to play baseball on the sandlots.

By the age of 13, Fred was good enough to play for the Keystone Club, a local all-star team of Girard’s best amateur and industrial players. The Keystones, “an amateur club of professional abilities,” also included future major leaguers Jack Allen and Ed Cushman, both of whom were several years older than Ely.4 As Fred grew to his adult height of 6-feet-1 — with a listed weight of 155 pounds, his stick-figure likeness naturally led to the moniker of “Bones” — he continued to develop his skills for amateur teams around western Pennsylvania.

In 1884, while pitching for a team from nearby Meadville, Ely caught the eye of “Orator” Jim O’Rourke, manager of the National League’s Buffalo Bisons.5 Ely was signed by the Bisons and given a chance to start just two weeks after his 21st birthday. His major-league (and professional) debut on June 19 against the last-place Detroit Wolverines was a disaster. He allowed 15 runs on 17 hits in five innings before he was mercifully relieved in an 18-2 loss.6 It was his only appearance for the Bisons.

Ely spent the next year building a reputation as a strikeout pitcher in stints with Youngstown (Ohio) of the Interstate League and Binghamton of the New York State League.7 He picked up the nickname “Corkscrew” because of “a peculiar curve he threw,”8 but he had little control over the pitch, which might have been an early variation of the knuckleball. When he returned to the majors with the Louisville Colonels in 1886, he struggled again, going 0-4 with a 5.32 ERA in six appearances. Manager Jim Hart saw potential but encouraged him to try another position.9

In 1887, Ely moved back to Binghamton and hooked on as a pitcher and outfielder with the Crickets of the International League, an integrated minor league that featured some of the best African-American players of their day, including future Hall of Famer Frank Grant, Moses Fleetwood Walker, and George Stovey. At Binghamton, Ely was teammates with the veteran black infielder John “Bud” Fowler and pitcher William Renfro. Fowler had been playing professional baseball since the mid-1870s, before Jim Crow laws had taken full effect around the country. But racial enmity and resentment among the white players in the International League and elsewhere had been growing for years, and this brief, tolerant era of integration would soon come crashing to a halt.10

Ely started the season slowly; after allowing 27 runs in his first three starts as a pitcher, he became the team’s regular left fielder as Binghamton sank into ninth place. Fowler, meanwhile, was hitting .350 and playing superbly at second base. In June, the frustration and racial tension boiled over when Crickets outfielder Buck West refused to take the field with his dark-skinned teammates.11 West rallied the other white players on the team and circulated a petition demanding the release of Fowler and Renfro; Ely was among the signers.12 Binghamton team directors fined the players $50 apiece, but acquiesced to their demands. Fowler was released on June 30 and Renfro soon afterward. Ely replaced Fowler as the team’s starting second baseman until the season ended.13

Two weeks later, on July 14, the International League formally banned its teams from signing any more African-Americans.14 That same day, Cap Anson of the Chicago White Stockings refused to take the field for an exhibition game against Newark and its black pitcher, George Stovey. While Stovey, Fleet Walker and other black players already in the league were allowed to continue playing, they could see the writing on the wall.

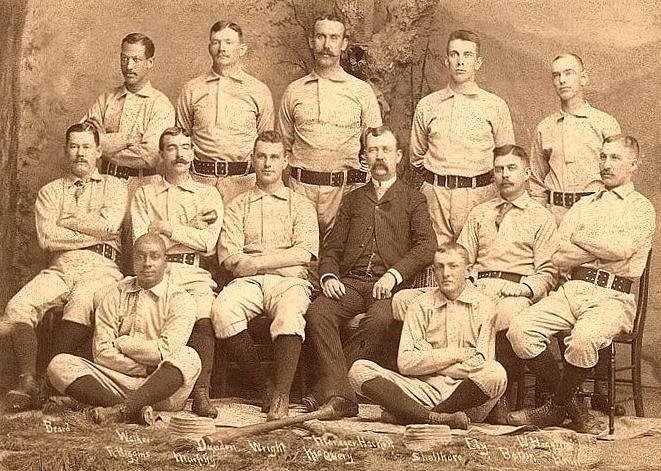

1888 Syracuse Stars. Moses Fleetwood Walker is at the top left, Robert Higgins at bottom left. Bones Ely is top row, second from right.

In 1888, the IL dropped from 12 teams to eight and Ely moved to the Syracuse Stars, where he was teammates with two more black players, Walker and pitcher Robert Higgins.15 Ely, despite his participation in the Binghamton uprising, seemed to have no apparent issues playing with Walker and Higgins, who contributed mightily to Syracuse’s winning season. Walker hit a home run in the Stars’ pennant-clinching victory over Albany, and the championship team was greeted by 25,000 fans and “a royal reception” at the Globe Hotel upon its return home.16 Ely had a strong year, hitting .284 with 22 doubles, 11 triples, and 47 stolen bases in 112 games, mostly in left field.

But the 17-game winner Higgins, fed up with the racism he had experienced in baseball, quit the team and returned to his barber shop in Memphis. Late in the 1889 season, Walker — the league’s last remaining black player — was released by the Stars, cementing the official rule of segregation enacted two years earlier.17 No African-American would play in the International League again until Jackie Robinson made his debut with the Montreal Royals in 1946.

Ely stayed with the Stars through 1890, and at age 27, he logged his first significant time as a shortstop that year. Syracuse had been invited to join the American Association, a struggling major-league circuit that rivaled the National League, but the team disbanded after a seventh-place finish. Ely hit .262 in 119 games.

In the offseason, Ely reportedly signed18 with the Louisville Colonels, but when the regular season began he was playing with the St. Paul Apostles of the minor-league Western Association. Facing severe financial difficulties, the Saints relocated to Duluth in June and then folded, without enough money even to pay their players’ salaries.

Ely got in touch with Jack Chapman, his former manager at Syracuse who was now at the helm of the Colonels. What happened next almost got Ely kicked out of baseball, according to an unnamed Sporting Life correspondent:

One of the most ungrateful wretches in the base ball business is Ely. … When the Western Association went under, Ely wired Chapman, the Louisville manager who had been his personal friend for years, to send him $50 to pay his board, which was done. Later Ely arranged to play in Louisville, Chapman providing a place for him when in reality he didn’t need his services. He was sent $100 in advance. After he had received the money, instead of going to Louisville to do something to earn it, he ‘double-crossed’ his old friend and went to the Brooklyn [National] League Club. Chapman, who had guaranteed the money advanced to Ely, is just that much out. He went security for the money because he believed Ely an honest and honorable man.19

Ely played out the rest of the season with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms (later called the Dodgers), hitting just .153 in 31 games, but the damage to his reputation was done. The American Association wouldn’t let him return until he paid back the money he owed to Chapman, but the league itself folded after 1891. Still, it took Ely nearly two seasons before he made it back to the majors. After inexplicably leading the Southern League with 19 home runs in 1893 — including a three-homer game on July 5 against New Orleans — Ely signed with the St. Louis Browns of the National League.

At 30 years old, Ely finally got his first chance to play regularly in the major leagues. Ely was installed at shortstop in place of Jack Glasscock, a veteran known as the “King of Shortstops” who had been traded away by the Browns in June. Taking advantage of a rule change that moved the pitching mound back from 50 feet to the modern distance of 60 feet, 6 inches, Ely blossomed as a hitter and made the most of his opportunity.

With his newfound power stroke, Ely led the Browns in home runs with 12 in 1894, more than doubling the total of his teammate, Roger Connor, one of baseball’s early career home run champions. He hit .306 with 12 triples and 23 stolen bases and, although he led the league in errors with 79, he turned heads with his energetic play at shortstop.

Nearly 100 years before tall shortstops like Cal Ripken Jr. and Alex Rodriguez would “redefine” the position, Bones Ely was already proving it was possible to be a 6-footer who could fill that key defensive role. According to Baseball-Reference.com, no shortstop in the 19th century was taller than Ely’s listed height of 6-feet-1.20

In 1894, Ely married 23-year-old Anna Stow, from his hometown of Girard, Pennsylvania. After the death of a relative left Fred with “a snug little fortune,”21 the Elys lived comfortably in Conneaut, Ohio, across the state line from Girard, without the need to depend solely on his baseball income. He bought an interest in a hardware store in Girard and later invested in Conneaut’s daily newspaper. He also had a “finely equipped gymnasium” built near his home to stay in shape during the offseason.22

Soon after their marriage, Anna fell sick with typhoid fever and Fred left the Browns in August to care for her when her health was at its worst. It took her several years to fully recover. In the meantime, Fred himself became afflicted with rheumatism, which caused him to miss the final two weeks of the 1895 season. He told Sporting Life that he would have sat down earlier, but “was afraid of being blacklisted.”23 This comment stemmed from a confrontation he had with the Browns’ mercurial owner, Chris Von der Ahe.

After Ely made a crucial eighth-inning error in a loss to the Cincinnati Reds in June, Von der Ahe ordered manager Al Buckenberger to fine him $25 on the spot. Buckenberger ignored the order. “I refused to fine the greatest ball player in the business for making a blunder which anyone is liable to make,” he said.24 The insubordination cost Buckenberger his job. When the manager told Ely what had happened, the infuriated shortstop “said things which gave the German [Von der Ahe] to understand that he wouldn’t play ball in St. Louis again unless he was forced to.” The National League considered suspending Ely for his “use of contemptuous and disrespectful language,”25 but Von der Ahe worked out a trade to the Pittsburgh Pirates instead.

Ely joined a Pirates team, under manager Connie Mack, that was old and underachieving, but it was here where he found his niche. Future Hall of Famer Jake Beckley, the Pirates’ only star, was traded away in midseason as the team stumbled to a sixth-place finish. Ely hit .285 and played 128 games at shortstop, where he was frequently singled out in the newspapers for his heady play. Mack was fired near the end of the 1896 season.. After a single season under player-manager Patsy Donovan, the Pirates hired Bill Watkins, Ely’s old boss from St. Paul and St. Louis. Watkins immediately named Ely the team captain.

Perhaps the added responsibility weighed on Ely’s performance, as he slumped to a .212 average in 1898. He even resorted to batting left-handed late in the season. But he led National League shortstops in fielding percentage (.943) and ranked second with a career-high 527 assists. Sporting Life praised his play: “Captain Fred’s fielding ability and strategy are well known, and with a few more base hits, his time as a first-class League man is not over for years to come.”26

Ely rebounded in 1899 to hit .278 and drive in 72 runs for the Pirates. On June 27 he experienced one of the greatest moments of his career when he hit a game-tying, inside-the-park home run with two outs in the ninth against the defending league champion Boston Beaneaters. “Pandemonium reigned supreme”27 at Exposition Park and, after the Pirates won the game in the 10th, Ely was celebrated by a Pittsburgh newspaper with a poem in his honor:

Aye, from the jaws of dire defeat a victory was snatched

And poor old Boston sneaked away, undone and overmatched.

Ah, boys, that was a record. Other feats may shine, but none

Past or present, figures in the class with Ely’s great home run.28

That was the high point of Ely’s Pirates career, for in the offseason the team was shaken up and the mediocrity of the 1890s gave way to the National League’s first dynasty of the 1900s. As the NL prepared to contract to an eight-team league, Louisville Colonels owner Barney Dreyfuss engineered a deal in which he took over the Pirates and sent all of Louisville’s best players to Pittsburgh. Fred Clarke took over as manager and he brought with him Honus Wagner, Deacon Phillippe, Tommy Leach, and Rube Waddell.

The Pirates remained in the pennant race all year long in 1900 and finished 4½ games behind Brooklyn. Ely played 130 games at age 37, but his .244 average made him by far the weakest bat in the lineup. His defense remained strong, however, as he ranked second in assists and fourth in fielding percentage among NL shortstops.

By 1901, the upstart American League was challenging the NL’s monopoly as a major league — and the AL enlisted Ely to help recruit more players. Third baseman Jimmy Williams, Ely’s best friend on the team, had already jumped from the Pirates to the Baltimore Orioles and Dreyfuss quickly became suspicious that others were planning to follow. In July, Ely, who had been beset by nagging injuries for years, begged out of the lineup because of a sore finger. Clarke, who was aware of Dreyfuss’s suspicions, ordered Ely to play, threatening to kick him off the team if he disobeyed. Ely refused. Two days later, Dreyfuss gave him an unconditional release and his National League career came to an end.

This incident set in motion Honus Wagner’s move from the outfield to shortstop, where he would become arguably the greatest player baseball has ever seen at the position. The 27-year-old Wagner, in his fifth year in the majors, was reluctant to make the switch. As Clarke later told the story, Wagner declared that Ely “was a popular idol and the man who took his place would have a rough time of it.”29 Wagner did get hassled by Pittsburgh fans at first, but he quickly won them over as the Pirates cruised to their first of three consecutive NL pennants.

Ely was quickly picked up by his old manager Connie Mack, now in the American League with the Philadelphia A’s, for the remainder of the season. He wrapped up his major-league career in 1902 with the Washington Senators, playing more than 100 games at shortstop for the ninth straight year. Only a handful of other shortstops have ever played as many games (1,182) after age 30 as Ely, and none of them got his start as late as he did.30 In 14 major-league seasons, with eight different clubs, Ely batted .258 with just over 1,300 hits.

In 1903, Ely joined the Portland Browns of the Pacific Coast League, an independent league that had broken away from the established Pacific Northwest/National League. The PCL would soon become the dominant source of baseball on the West Coast for decades to come. Ely was named manager of the Portland club in September, just months after the other team in town, the Portland Green Gages of the PNL, left for Salt Lake City.31 With stability on the horizon, Ely convinced his brother Benjamin to help him purchase a controlling interest in the Browns. They paid a reported $20,000 to buy the team.32

Team ownership didn’t suit either of the Ely brothers, who couldn’t agree on the direction of the team. Ben reportedly “froze out”33 his brother on business decisions and Fred resigned as manager in May, with Portland in last place at 11-32. Daniel Dugdale of Seattle, a Pacific Northwest League veteran who had once vowed to crush the PCL, was hired to replace him, but he didn’t last long under Ben Ely’s stewardship, either.34 At the end of the season, the Elys sold the club outright for $9,000 to William McCredie and his nephew Walter, who would revitalize the club and lead Portland to five PCL pennants between 1906 and 1914.

Ely’s baseball days were over, but he stuck around Portland for several years, occasionally participating in exhibition games or coaching amateur teams before embarking on a career as a traveling telephone salesman based out of Omaha, Nebraska.35 By 1914 he had moved back to the Pacific Northwest, where he and his brother Ben owned a hotel in Centralia, Washington.36

In 1920, Fred and Anna moved to Berkeley, California, where they would spend the rest of their lives. Fred managed several businesses and Anna worked as a stenographer and office assistant.37 He had been a voracious reader in his spare time as a ballplayer,38 and in retirement he also enjoyed hunting and fishing. He lived long enough to see Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Montreal Royals and then the Brooklyn Dodgers; Ely was one of just a handful of players alive who had played professional baseball during the previous era of integration.39

In his final years, Fred suffered from dementia and he died at the Napa State Hospital on January 10, 1952, at the age of 88. His wife died just two months later, on March 18, a day after her 81st birthday. They were both cremated.40

Author’s note

This biography is dedicated to the feline Bones Ely, another veteran who made the most of an opportunity to make good later in life. All the pets in our household get named after Deadball Era ballplayers, but I knew very little about the real Ely when we adopted this 7-year-old, 6-pound “bag of bones” and chose Bones as her namesake.

Photo credits: Bones Ely and 1888 Syracuse Stars, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Additional Sources

Burgos Jr., Adrian, Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007).

Laing, Jeffrey, Bud Fowler: Baseball’s First Black Professional. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2013).

Lieb, Frederick G., The Pittsburgh Pirates. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948).

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams. (New York: Gramercy Books, 1970).

Zang, David W. Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart: The Life of Baseball’s First Black Major Leaguer. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

Notes

1 Arthur D. Hittner, Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s ‘Flying Dutchman’ (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1997), 93-96; Cincinnati Enquirer, July 27, 1901.

2 1850-80 U.S. Censuses, accessed online at Ancestry.com. Benjamin Whitman, ed. Nelson’s Biographical Dictionary and Historical Reference Book of Erie County, Pennsylvania (Erie, PA: S.B. Nelson, 1896), accessed online at Archive.org.

3 History of Otsego County, New York (Philadelphia: Everts & Fariss, 1878), 362.

4 John Miller, A Twentieth Century History of Erie County, Pennsylvania. (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1909), 852-853.

5 Chicago Inter Ocean, June 20, 1884. Ely, pitching for Meadville in an exhibition game against the visiting Bisons weeks earlier, had reportedly struck out 12 Buffalo hitters in an eye-opening performance.

6 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 20, 1884.

7 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 16, 1885; Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 8, 1885; August 10, 1885; August 16, 1885; September 19, 1885; October 2, 1885.

8 Sporting Life, December 19, 1896.

9 Louisville Courier-Journal, June 25, 1886.

10 For a more comprehensive discussion of integration in the International League, read Jerry Malloy, “Out at Home: Baseball Draws the Color Line, 1887,” The National Pastime, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Cooperstown, NY: SABR, Fall 1982), 14-28.

11 Brian McKenna, “Bud Fowler,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/200e2bbd. Accessed online May 24, 2016.

12 Gregory Bond, “Race, Manliness, and the Color Line in American Sports, 1876-1916,” Ph.D. dissertation (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2008), 288-90.

13 Although Bond’s paper cited above claims that Ely had “the most to gain” by signing the petition because Fowler played “his best position,” Ely had rarely played the infield during his professional career to this point. Box scores from the Sporting Life newspapers of 1887 show that Ely did not appear regularly at second base until after Fowler was released. In August, the Binghamton team folded due to financial difficulties.

14 Malloy, “Out at Home,” 24-25.

15 Higgins had been the subject of unwanted national attention in 1887, when his white Syracuse teammates were accused of intentionally making errors behind him in a game against Toronto. Two players had also refused to appear in a team portrait with him.

16 Sporting Life, October 3, 1888.

17 John R. Husman, “Moses Fleetwood Walker,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9fc5f867. Accessed online on May 29, 2016.

18 Sporting Life, January 10, 1891.

19 Sporting Life, October 13, 1891.

21 Atlanta Constitution, March 26, 1893.

22 Sporting Life, November 11, 1899.

23 Sporting Life, September 28, 1895.

24 The Sporting News, January 11, 1896.

25 Sporting Life, December 28, 1895.

26 Sporting Life, October 1, 1898.

27 Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, June 28, 1899.

28 Oregon Daily Journal, January 30, 1904.

29 Winfield (Kansas) Free Press, September 16, 1911.

30 Entering the 2016 season, Ely ranks 20th all-time in most games played at shortstop after age 30. See http://bbref.com/pi/shareit/HrS9O.

31 Dennis Snelling, The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2011), 20-24.

32 San Francisco Call, January 25, 1904; The Oregonian, January 25, 1904.

33 The Oregonian, December 31, 1911.

34 Snelling, 27-28.

35 The Oregonian, March 29, 1908; 1910 US Census, accessed online at Ancestry.com.

36 United States Tobacco Journal, September 26, 1914.

37 1920-40 US Censuses, accessed online at Ancestry.com.

38 Sporting Life, May 31, 1902.

39 Malloy, “Out at Home,” 14.

40 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology: The Post-Baseball Lives and Deaths of More Than 7,600 Major League Players and Others (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2003), 120.

Full Name

William Frederick Ely

Born

June 7, 1863 at North Girard, PA (USA)

Died

January 10, 1952 at Imola, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.