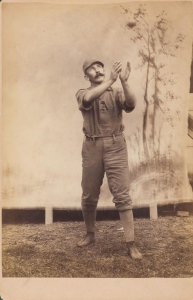

Fred Mann

On July 8, 1777, thirty-four delegates gathered at the Windsor Tavern and adopted the first Constitution of the Free and Independent State of Vermont. Fittingly, less than a century later the first Green Mountain Boy of Summer learned to play baseball in that same town. Though Fred Mann was born on April 1, 1858, in the Northeast Kingdom village of Sutton, his family moved to Windsor during the 1860s.

On July 8, 1777, thirty-four delegates gathered at the Windsor Tavern and adopted the first Constitution of the Free and Independent State of Vermont. Fittingly, less than a century later the first Green Mountain Boy of Summer learned to play baseball in that same town. Though Fred Mann was born on April 1, 1858, in the Northeast Kingdom village of Sutton, his family moved to Windsor during the 1860s.

The Manns lived on Ascutney Street, just down the street from Windsor State Prison. Fred and his sister, Hattie, attended Windsor High School, where Fred had a perfect attendance record his junior and senior years. He was one of 13 students who graduated in 1876, and at the graduation ceremony he opened the program with an oration entitled “The Children’s Crusade.” A few weeks later Fred marched with the volunteer firemen in the annual Fourth of July parade, which took on special importance as a celebration of the nation’s Centennial. And of course he was a member of the “Windsor boys” baseball team that was to play a game as part of that celebration, but it was one of many events washed out by heavy rains.

Windsor calls itself the “Birthplace of Vermont,” but it may also be the birthplace of Vermont baseball fever. The sport was so popular in town that by July 1875 the editors of The Vermont Journal chided their readership that it may have become too important in the life of the community:

The “national game” of base ball will soon give way to the more useful and practical science of rifle shooting, and the liability to broken bones and blackened eyes is nothing in the latter compared to that of the former. Besides, in case of a public emergency so vital to the country’s welfare as the unpleasantness of 1860, the value of an organization of off-hand rifle shooters could scarcely be estimated….

But the readership failed to take heed. In the summer of 1876 The Journal reported several matches in Windsor. Examples:

The Jones and Lamson mill boys have challenged the town boys to a game of Baseball, to be played on the grounds back of the depot on Saturday, the 22nd at 3:30 o’clock.

On Thursday, 21st, there will be a game of Base Ball, for a prize, given by the [Fair] Association, between the Base Ball Club of Windsor and the Alpha Juniors of Springfield on the Fair Grounds.

The Shoe Shop hands challenged the clerks in the stores in the village to play a game of ball, Wednesday evening which resulted in a victory to the club — after four innings — by a score of 40 to 9. A large crowd collected on the Commons to witness the game. The uniform was unique in the extreme.

A game of baseball was played, on Saturday between the “Livelys,” Capt. Wm. Pollard and the “Slowlys,” Capt. E.S. Cole — the “Livelys” winning by a score of 14 to 8.

Those games were not pick-up events, nor part of any organized league, but rather arranged affairs with captains and commercial or civic sponsors. That was the world of amateur baseball in which Fred Mann learned his trade.

Mann’s exact path from Windsor to the roster of the National League’s Worcester Ruby Legs in 1882 is not entirely known. The Boston Globe mentions him playing in 1880 for the Westfield Firemen and the following year for the Hammond “nine” of the Worcester Shop League. Presumedly Mann hoped to land a position on a traveling professional club. In The Ball Clubs, Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella wrote that in those days semi-pro teams “derived much of their revenue from exhibition games with National League teams and it was not unusual for a League nine to visit a small city, sign up one or more of the best players of the local organization and take them away.”

Mann’s first break came on July 28, 1880, when the touring Washington Nationals came to Springfield, Massachusetts. The Nationals had already played exhibitions in Springfield against Cleveland and Chicago earlier that week, and now they were scheduled to play Cincinnati. On the day before the game, however, Washington’s right fielder became ill. Because the team toured with only one player per position, a local substitute was needed. In the summer of 1880, the best amateur player in the Springfield area was 22-year-old Fred Mann of the Westfield Firemen. Batting ninth in the order, Mann failed to hit safely; the New York Clipper blamed Washington’s one-run loss on the “amateur who played right field.” Though his big break didn’t have a storybook ending, it wasn’t the last opportunity he received to reach the majors.

Just 40 miles to the east, Worcester, the second-largest city in Massachusetts, was fielding its first major league team. Powered by rookie center field sensation Harry Stovey, the league’s leading home run hitter, the Worcester Ruby Legs were en route to a surprising fifth-place finish in the National League, with a 40-43 record. That initial success proved short-lived, however. In 1881, plagued by team dissension, accusations of game-throwing and general rowdiness, the Ruby Legs fell to last place.

Going into the 1882 season, new manager Freeman Brown, vowing to field a team of men with good character, purged that gang of rowdies of all but six players. Among the new recruits was Fred Mann, the star of the Worcester Shop League the previous summer. During Worcester’s exhibition season Mann played third base, securing a place on the team by smashing two doubles and a triple among four hits in an 18-12 rout of Harvard College on April 22.

Once the National League season began, however, the 24-year-old rookie struggled. In 19 games, 18 of them at third base, Mann batted .234 with five doubles. Though he was by no measure the team’s worst hitter, his fielding percentage was .703, dismal even for a third baseman in an era when players didn’t wear gloves. His teammates fared no better; for the season, the Ruby Legs’ winning percentage of .214 was the worst in the majors since 1876. After a 14-game losing streak and a 9-32 start, Freeman Brown was fired and several of his players released. One of them was Fred Mann.

With the upstart American Association challenging the National League’s monopoly on the professional game, 1882 was a fine time to be a professional baseball player looking for a job. Only two weeks passed between Mann’s release by Worcester and his first appearance for the A.A.’s Philadelphia Athletics on June 24, 1882. His new employers were typical of the owners in the rough-and-tumble American Association: one ran a saloon and bookmaking operation while another was a minstrel show producer and performer. Snobbish N.L. adherents dubbed the A.A. “The Beer and Whiskey League” because there was beer or liquor money behind all six of its founding teams, but the new league gave fans what they wanted: affordable ticket prices, Sunday baseball where allowed and a carnival atmosphere at the ballparks. In their first year, all six Association teams made money, drawing a higher combined attendance than the National League’s eight teams.

The Athletics had as much success on the field in 1882 as at the box office, finishing second to the Cincinnati Red Stockings. At third base, Fred Mann established himself as one of the team’s heaviest hitters. Batting third in the order, he finished second on the Athletics in slugging average and led the team in triples despite playing in only 29 of Philadelphia’s 74 games. But fielding remained a problem; game accounts from 1882 are strewn with comments like “Mann muffed an easy one” or “Mann’s error contributed to the loss.”

To expand the Association to eight teams in 1883, A.A. owners created new teams in New York City and Columbus, Ohio, stocking them predominantly with players from existing franchises. One of the founders of the Association, “Hustling” Horace Phillips had intended to operate the Philadelphia franchise in 1882 before he was maneuvered out of it. Given the opportunity of starting the Columbus Buckeyes in 1883, he sought revenge on the Philadelphia owners by selecting Fred Mann in the expansion draft.

Over the next four seasons Mann blossomed into a solid major leaguer. Recognizing that third base failed to take full advantage of Mann’s footspeed, Phillips moved him to center field. Before long he was winning accolades even for his defense. The New York Clipper reported Mann “playing brilliantly in the field,” while Sporting Life credited him for “making difficult catches in the outfield.” As for offense, the Clipper called him “one of the hardest hitters in the country.” Usually batting clean-up, Mann had perhaps his greatest season in 1884, leading the Buckeyes in slugging average, triples and home runs. He remained one of the club’s top hitters after 1885 when Columbus merged with the Pittsburgh Alleghenys to form one of the Association’s best teams.

In 1887 the Pittsburgh team jumped to the National League and became the Pirates, but for some reason did not take Fred Mann with them. Before spring training the Vermonter signed with the A.A.’s Cleveland Blues, a team of castoffs and untested amateurs hastily thrown together to fill the void in the Association left by the departing Pittsburgh franchise. Predictably, the Blues quickly dropped to last place, but at least Mann provided occasional heroics. In a losing effort against the New York Metropolitans on May 16, for example, he slugged a grand slam, though the term had not yet been invented; the Clipper reported that “Mann made a home run in the ninth inning when three men were on the bases.”

On July 22 Fred Mann, though leading the Blues with a .309 average, was unaccountably released. No matter: as an established player now, the center fielder signed the same day for a second tour of duty with the Athletics. Mann’s acquisition allowed his former Worcester teammate, Harry Stovey, to move from center field to his preferred position at first base. Mann also did his part to improve the Athletics by batting .275 down the stretch, but Philadelphia still failed to catch Charlie Comiskey’s St. Louis Browns, en route to their third consecutive world championship.

That offseason the Browns entered into a pair of transactions that shocked the baseball world. First they sold star center fielder Curt Welch to the Athletics for $3,000; then they traded their outstanding shortstop, Bill Gleason, to Philadelphia for shortstop Chippy McGarr, catcher Jocko Milligan and Fred Mann. On the face of it, the trade must have come as a pleasant surprise to Mann. Everyone expected him to be a starting outfielder on the strongest club in the Association, as demonstrated by the inclusion of four different poses of Mann in a Browns uniform in the Old Judge baseball card series. During the 1888 preseason he did nothing to disrupt those expectations, playing right field, batting second, and collecting more than his share of hits.

So it must have been a great surprise for Mann to read the following item in the “late news” section of the April 25 edition of Sporting Life:

Fred Mann, recently signed by President Von der Ahe to cover either right or center field, will be released either today or Monday. Young Lyons is showing up in such good shape fielding, batting and running the bases that he will be kept in right field and McCarthy will play center. No fault was found with Mann’s work, but President Von der Ahe is a convert to young blood.

As it turned out, Mann was indeed released. Harry Lyons batted a meagher .194 in his only full season with St. Louis, but Tommy McCarthy went on to become a Hall of Famer and the Browns won their fourth consecutive American Association pennant.

After his release by St. Louis, Fred Mann signed a minor league contract with Charleston, South Carolina, of the Southern League. When the league folded in late-summer, he was recruited to become captain of the Tri-State League’s Columbus Senators, returning to the city where he had established himself as a solid major leaguer five years earlier. In 1889 Mann signed with Hartford of the newly-formed Atlantic Association, but at 31 his skills were beginning to fade. Playing first base, he batted only .235. He was credited with 40 stolen bases in 81 games, but that inflated figure is accounted for by the practice of awarding stolen bases not only for clean steals but also for extra bases taken through daring baserunning. Mann was nearing the end, and the 1890 season, in which he batted only .169 in 22 games, was the last for both him and the Atlantic League.

Settling down at 24 Wilbraham Avenue in Springfield, the city where he played his first game against major league competition a decade earlier, Mann spent his last 20 years as a hotel proprietor and bartender. His life was cut short by prostate cancer on April 6, 1916, and he is buried in Springfield’s Oak Grove Cemetery. Of the places where Mann worked, both the Feeding Hills House and the Brightside Inn no longer exist, but the Gilmore House where Mann once tended bar still stands — that and his indelible record in Total Baseball as the first of the Green Mountain Boys of Summer.

Sources

A version of this biography originally appeared in Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993, edited by Tom Simon (New England Press, 2000).

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers.

Full Name

Fred J. Mann

Born

April 1, 1858 at Sutton, VT (USA)

Died

April 16, 1916 at Springfield, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.