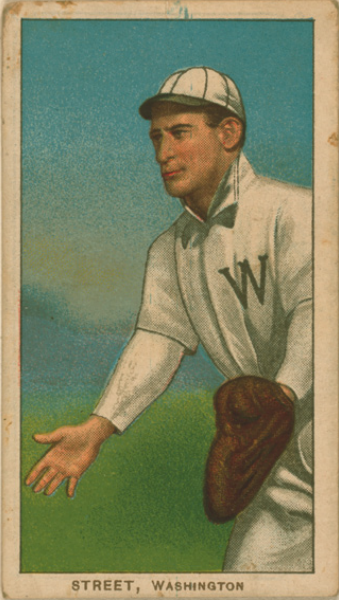

Gabby Street

Gabby Street may not have been much of a batsman in his career. His high mark for batting average was .238 in 1905, a season he split between Cincinnati and the Boston Beaneaters. Perhaps he was aided by only 105 at-bats, the second lowest total of his career. There may have been a slight decrease in that .238 average had he made more trips to the plate. His strength as a big-league catcher was how he handled his position, worked the pitching staff. During his time in Washington, Street was a favorite backstop of Walter Johnson. “You don’t see Gabby’s kind of a catcher anymore. He never hit much, but what a receiver he was—big fellow, a perfect target, great arm, slow afoot, but spry as a cat on his feet behind the plate, always talking, always hustling, full of pep and fight,” said Johnson. “Gabby was always jabberin’, and he never let a pitcher take his mind off the game. When we got in a tight spot, Gabby was right out there to talk it over with me. He never let me forget a batter’s weakness.”[fn]Alan Gould, Associated Press, “Gabby Street, Ace of the Cards,” September 20, 1931.[/fn]

As a catcher, Street honed his ability to take charge. It was his capability as a leader that served him well in World War I, and as a pennant-winning manager for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1930 and 1931. Gabby led the Cards to their second world championship in 1931. He was proclaimed a “Miracle Man” for delivering a title to the Mound City. “Miracle Man? Who? Me? Hell no! I’m just an old ballplayer with a bunch of fighting cocks on my roster that woulda won the pennant with Butch the Batboy directing them. Forget the ‘Miracle Man’ stuff, woncha?” said the self-deprecating Street.[fn]The Sporting News, October 2, 1930, 5.[/fn]

But what was it that makes fans remember Gabby Street? Ironically, it was for something outside the lines of a baseball diamond. No, it was not his appearance on the Simpsons episode “Homer at the Bat,” which aired on February 20, 1992. D’oh! Gabby had passed away 41 years earlier and he was appearing in pop culture.

No sir, Gabby Street was perhaps known for catching a ball dropped from atop the Washington Monument on August 21, 1908. Senators fans Preston Gibson and John Biddle had made a wager of $500 on whether the feat could be done. After all, the ball would travel 555 feet, and at a high rate of speed. Gabby was never one to be deterred from a challenge and set his place at the foot of the monument. Gibson and Biddle climbed to the top with a basket full of baseballs, and constructed a wooden chute so the ball would slide to arc away and clear the wide base of the enormous structure. The first 10 baseballs caromed off the base of the monument, so the chute was discarded and the pair of fans took turns throwing the ball from their perch. Gabby, dressed in street clothes, with arms outstretched over his head as if to corral a pop fly, made the successful catch on the 15th attempt. It was calculated that the baseball had picked up 300 pounds of force by the time it landed in Street’s mitt, which almost hit the ground from the impact. “I didn’t see the ball until it was halfway down,” said Gabby. “It was slanting in the wind and I knew it would be a hard catch.”[fn]Unidentified clipping from Street’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.[/fn]

As for Gabby, he went on his way to work. He caught Walter Johnson that day as the Nats defeated the Detroit Tigers, 3-1.

Charles Evard Street was born on September 30, 1882, in Huntsville, Alabama, one of seven children of Williams and Sis Street. “I played ball on the grammar and high-school teams there, and then at South Kentucky College at Hopkinsville,” Street said. “In 1900, a small Class-D league was formed, the ‘KIT’ League, the right name of which was the Kentucky, Illinois, and Tennessee League (also known as the KITTY League). I was offered $60 a month to catch for the Hopkinsville team (1903), and accepted. That was big money.”[fn]Ibid. The Street parents’ occupation is unknown.[/fn]

Street was sold the next season to Terre Haute (Indiana) of the Class-B Central League. His contract was then purchased by the Cincinnati Reds, and Street made his major-league debut on September 13, 1904. He appeared in 11 games, backing up starting catcher Admiral Schlej. The Reds had called up another catcher in 1904, Branch Rickey from Dallas of the Class-C Texas League. But when Rickey refused to play baseball on Sundays he was returned to Dallas, thus clearing the way for Street to join the team.

In 1905 Street began the season with Cincinnati but was “loaned to the Boston Beaneaters” on June 5. Both of Boston’s catchers had been injured in the June 3 game and so the National Commission facilitated a loan of Street to the Beaneaters.[fn]Chicago Tribune, June 6, 1905.[/fn] He hadn’t gotten off to a good start for Boston, committing four errors in the June 7 game against the Cubs, two of them on throws which effectively cost Boston the game.[fn]Boston Globe, June 8, 1905. Street’s four errors in 18 chances in his three games with Boston saddled him with a .778 fielding percentage in the short stay, from which he also returned with a broken finger.[/fn] The very next day he himself was hurt, his index finger hit by a pitch that broke it, but with no other catcher available he had it bandaged and continued.[fn]Boston Globe, June 10, 1905.[/fn] The 1905 Boston team was one of special note, as four different starters totaled 20 or more losses on the year. The feat was repeated again in 1906. By the time Boston passed through Cincinnati, Street had been returned to the Reds, on June 15.[fn]Washington Post, June 16, 1905.[/fn]

Back with the Queen City, remaining in the role of a backup catcher, Street caught in 31 games in all for the Reds. His contract was again purchased, this time by San Francisco of the Class-A Pacific Coast League in February 1906. He spent the next two seasons in the City by the Bay, although on April 18, 1906, he almost got dumped into the Bay. “I was living in the Golden Gate Hotel, patronized largely by baseball players and members of the theatrical profession and during the wee hours of April 18 of that year, I was thrown from my bed,” said Street. “Out in San Francisco they still refer to the Act of God which tossed me from my bed as ‘The Fire,’ but the force that removed me from my mattress to the floor was an earthquake. Aroused, I rubbed my eyes, looked out the window and saw buildings crumbling, and having heard whispers of quakes, I headed for the street. If I live to be a hundred I shall always remember that scene. As we hit the street, en masse, the rear of the hotel collapsed and the water tank on the roof, halved by the second shock, washed everyone of us. I walked through showers of brick and mortar to the Golden Gate Park where I spent the night.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

Street was ready to jump the Seals and head to an “outlaw” league and play in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Although his exit from San Francisco was delayed, he eventually made it to the Keystone State, playing in 102 games for the Millionaires club of the Independent Tri-State League. However, he returned to the Seals for the 1907 season, appearing in 159 games and registering a .231 batting average in 523 at-bats. It was the most playing time Street had received since Terre Haute.

Persistence paid off for Street, and his contract was sold to the Washington Senators. Of the 504 games Street played in the major leagues, 429 were over the next four years (1908-11) with Washington. His calling card was his defense, as he led the league in putouts and double plays in both 1908 and 1909. In 1910 he was atop his peers with a fielding percentage of .978. In today’s vernacular Street’s batting average would be characterized as worthy of the “Mendoza Line,” as his average with the Senators was a meek .210. Catchers of the day were never expected to hit that well, and in any event Washington was not fielding a championship team in those years, finishing no better than seventh place in the American League and no closer than 22½ games back of the pennant winner.

Importantly, Walter Johnson favored Street, acknowledging him as a first-rate catcher. “He always kept the pitcher in good spirits with his continual chatter of sense and nonsense,” said the Big Train. “ ‘Ease up on this fellow, Walter, he has a wife and two kids,’ he would call jokingly when some batter was hugging the plate and getting a toehold for a crack at one of my fast ones. ‘This fellow hasn’t had a hit off you since you joined the league,’ might be his next remark and so on throughout the game.”[fn]Henry W. Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 55.[/fn]

On April 14, 1911, Cleveland pitcher Addie Joss died at 31 of tubercular meningitis. Joss, who was one of the great pitchers of the Deadball Era, or any era for that matter, was also well-respected and well-liked by his peers. His Cleveland teammates began to canvass other American League players to play in a game to raise funds for Joss’s widow, Lillian, and her two children. The game was played on July 24, 1911, at Cleveland’s League Park. It was an unofficial “All-Star Game” that predated Arch Ward’s concept by 22 years. It was also one of the greatest collections of baseball talent as the Cleveland Naps took on the American League stars. The Naps were led by Joe Jackson, Napoleon Lajoie, and Jack Graney. The All-Stars were rightly named; they included Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Sam Crawford, Frank Baker, Eddie Collins, Hal Chase, and Walter Johnson. Street volunteered to participate. “As far as I am concerned, that outfit can stand as the all-star team of all time, outside of the backstop of course,” He said. “I didn’t need to be good with that bunch. Cy Young started on the mound for Cleveland as I recall it and he was still pretty good for an old fellow, but these fellows just blasted him.”[fn]Gould.[/fn] Attendance for the game was reported to be 15,270, and $12,914 was raised for Lillian Joss.[fn]Baseball-almanac.com.[/fn]

On February 17, 1912, Street was dealt to the New York Highlanders (now the Yankees) for utility players John Knight and Rip Williams. But Street was suffering from inflammatory rheumatism, and his playing time was limited to 29 games. He was sold to Providence of the Double-A International League. From 1913 to 1917, Street played in the Class-A Southern Association with both Chattanooga and Nashville.

Gabby Street became known as Sergeant Street when he enlisted in the Army in March 1918. As Street put it, he was going off to fight in the “real” World Series.

“I was sent to Fort Slocum, N.Y., and everybody interested in baseball thought it was great that I should be on hand to catch the army team. I finally convinced my lieutenant that I joined the army to fight, pointing out that I could have continued playing baseball for a salary. I was one of the first 50,000 to get over and took part in three major engagements: Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel and the Argonne. That St. Louis regiment, the 138th, was as fine as an outfit as I ever saw, and I was proud to be attached to it,” said Sergeant Street.[fn]The Sporting News, October 2, 1930, 5.[/fn]

Street was assigned to the 1st Gas Regiment, Chemical Warfare Division. He and his men joined the 138th in the Battle of the Argonne. Street’s men held down a smoke screen for the 138th Infantry on September 26, 1918. A machine-gun bullet from a German airplane punctured his right leg on October 2, 1918. He was awarded the Purple Heart, and his fighting days were at an end.

Street returned to Nashville after his discharge, but at the age of 36 his playing days were coming to an end. Street’s goal was to return to the major leagues as a coach or manager. And he paid his dues, serving as a player-manager for the next nine seasons for six teams in three leagues. While managing Joplin (Missouri) of the Class-C Western Association in 1922-23, he met Lucinda Rona Chandler of Joplin. They were wed in 1923 and had two children, Charles Jr. and Sally.

The St. Louis Cardinals were building a juggernaut under the direction of general manager Branch Rickey. The Redbirds topped the Yankees in 1926, winning the franchise’s first world championship in 1926, but were swept by New York in 1928. Sandwiched between the two pennant-winning seasons was a second-place finish by 1½ games to Pittsburgh. Gabby Street was added to new St. Louis manager Billy Southworth’s coaching staff in 1929, but the Cardinals fell on hard times, finishing in fourth place, 20 games back. Southworth was replaced by Bill McKechnie just after midseason. St. Louis owner Sam Breadon had a penchant for making changes, especially managers. For the 1930 season, he replaced McKechnie with Street. Street was Breadon’s sixth new manager to start a season in six years. Breadon said he had hired Street “because I believe he is just the man to give us a winner. He knows baseball through and through, is smart, a hustler, and the game is his main interest in life. The players like him and respect him. He was glad to get the job. It was unanimous.”[fn]Gould.[/fn]

The team Street took the reins of was by no means a rebuilding project. Jim Bottomley, Frankie Frisch, George Watkins, Jimmie Wilson, and Chick Hafey anchored a formidable lineup in which each starter hit over .300 and the team scored 1,004 runs. The pitching staff was led by Jesse Haines, Bill Hallahan, and spitball hurler Burleigh Grimes. Street did not have the burden of developing players as he had in the minor leagues. Indeed it was a smart manager who recognized the talent on his club and did not tinker with it too much. “The difference is I don’t have to show these fellows how to play ball,” said Street. “Most of them have had long experience. They do the work and make my job easy for me.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

On July 31 the Cardinals were tied with Pittsburgh for fourth place, 11 games behind front-runner Brooklyn. But St. Louis went on an incredible streak in the final two months of the season, going 23-9 in August and posting a 21-4 record in September, clinching their third pennant with two games to play. On the last day, a young hurler named Dizzy Dean toed the rubber in his first major-league start. The brash youngster came as advertised, beating the Pirates 3-1 on a three-hitter. Street could add “miracle worker” to his other monikers, Gabby and Ol Sarge.

The Cardinals were matched up with the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. Frisch came down with a case of lumbago. He played, but his back was covered in bandages and plaster. He hit .208 for the Series. Only one Cardinal batted over .300 for the Series, shortstop Charlie Gelbert, who hit .353 while playing on a sore leg that was heavily wrapped each game. Lefty Grove and George Earnshaw each won two games as the A’s took the Series in six games.

Frustration overcame Street as he dealt with Dean and his antics during spring training in 1931. Dean would often be late or just miss workouts and meetings altogether. “Let some of the other clucks work out for the staff. Nobody can beat me”[fn]John Heidenry, The Gashouse Gang (New York: Public Affairs, 2007), 51.[/fn] was a line Dean often fed to Street. The veteran players and Street had a respectful relationship and although Street might talk tough, he was extremely wellliked. There was no denying Dean’s ability, but he drove Street and later Frankie Frisch crazy with his clowning around. Dean was eventually sent down to Houston of the Texas League, where he spent the bulk of the 1931 season. Prophetically, Street remarked, “I think he’s going to be a great one. But I’m afraid we’ll never know from one minute to the next what he’s going to do or say.”[fn]Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 199.[/fn]

The 1931 season would prove that no miracle was needed. The Cards held a slim lead over the rest of the pack on May 30, then built on it and coasted to their second straight pennant with a record of 101- 53. The 48-year-old Street put on the catching gear for one last time on September 20, 1931, starting a game against the Brooklyn Dodgers and playing long enough to get one at-bat. That wrapped up a career in which he batted .208 in 504 major-league games, hit two home runs, and drove in 105 runs. A relatively new face in the Cardinal lineup was center fielder Pepper Martin. In his first full season with the Cards, Martin hit .300 and drove in 75 runs. Except for Mike Gonzalez and Frisch, the rest of the team were products of Rickey’s farm system. Their opponent in the World Series was again the Athletics. Before the Series, Connie Mack said of the Cardinals, “I don’t worry about their big hitters—Frisch, Bottomley, Hafey—but they’ve got a young man named Martin who bothers me. He’s the kind of aggressive, unpredictable who could be the hero or the goat.”[fn]Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years—1915-1931 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 616.[/fn]

Pepper Martin certainly was no goat, batting .500 with four doubles, one homer, five RBIs, and five stolen bases. Grimes and Hallahan each won two games. Grimes won the all-important Game Seven, 4-2, while Hallahan had what today would be recorded as a save. St. Louis scored two runs in the first inning, one on a wild pitch by Earnshaw, and one on an error by first baseman Jimmie Foxx. George Watkins hit a two-run homer in the third inning off Earnshaw to make the score 4-0, and the lead held up. The Cardinals had their second world championship. “I’ve seen a lot of great ballclubs in my day, but for pitching, hitting, spirit, and all-around balance, I would back my 1931 Cardinal team against any of them,” Street said.[fn]Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), 144.[/fn] Frisch agreed with his skipper: “There’s no question in my mind that the best club that I ever played with was the happily efficient Cardinal team of 1931.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

It may have been surprising that the Cardinals dropped to sixth place in 1932 with a 72-82-2 record. It did not get much better in 1933. Street was not around to see the end of the latter season, resigning on July 23 with a 46-45 record. Gabby’s undoing began in spring training, when the sportswriters began to write about his “board of strategy.” In essence, Street allowed some of the veteran players to assist him in the decisions he made on the field. The result was a cooperative team and two pennants. When the Cards started losing, Street’s way naturally began to take a hit in the press. Suddenly Street felt he was not getting the credit he deserved for the two pennants.

In a spring-training meeting in 1933, Street blew up at his team, telling them that he and he alone would be making every decision in the dugout. “Gabby didn’t like those stories about the Cardinal ‘board of strategy’ on the ballclub,” said Frisch. “There wasn’t going to be any board of strategy from there on. He’d crack the whip, he’d make all the decisions, he’d take all the responsibility, and maybe after the next pennant the Old Sergeant would get just a little bit of credit as manager of this club.

“Spoken or not, the sentiment was: ‘We’ll let him manage the ballclub, we’ll let him crack the whip, and we’ll let him get all the credit, and we’ll just keep our damned mouths shut.’ It hurt me to see the absolute divorce between manager and squad. I got him alone one day and asked him why in the world he had lost his temper and popped off like that to a club that thought so much of him. ‘Frank,’ he said, ‘I just got so damned sick of that junk in the newspaper that I couldn’t stand it any longer.’”[fn]Ibid. 163-164.[/fn]

Street returned to the minor leagues, managing the Mission (San Francisco) Reds of the Pacific Coast League (1934-35) and the St. Paul Pioneers of the American Association (1936-1937). He returned to St. Louis to manage the Browns in 1938. He was fired with 10 games left in the season and a record of 53-90. The Browns finished in seventh place, 44 games behind the New York Yankees. Street’s career record managing in the big leagues was 365-332, a winning percentage of .524.

Street, an avid golfer and quail hunter, did not stay away from baseball for long. With a nickname like Gabby, he was a natural for a color commentator on radio broadcasts. He started his second career in 1940, providing his unique insight to Browns games, and was eventually paired with a young Harry Caray to broadcast Cardinals games from 1945 to 1950.

Charles Evard Street died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 67 on February 6, 1951, in Joplin, Missouri. In 1966 he was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. His former broadcast partner Caray served as the host. “Gabby could talk because he lived through so much,” Caray said. “To be able to have this man as my friend was the greatest thing that could happen to me.”[fn]Street player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.[/fn]

And just how did Street get his nickname? “Down south, if you see a black boy, and want him, and don’t know his name, you yell ‘Hey Gabby.’ It works in St. Louis too. And if you don’t believe me, try it. To me, all black boys have been ‘Gabby’ and I got my nickname from the use of that word, and not, as is commonly believed, because I am a chatterbox.”[fn]The Sporting News, October 2, 1930, 5.[/fn]

This biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode ‘Homer At the Bat’ ” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Full Name

Charles Evard Street

Born

September 30, 1882 at Huntsville, AL (USA)

Died

February 6, 1951 at Joplin, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.