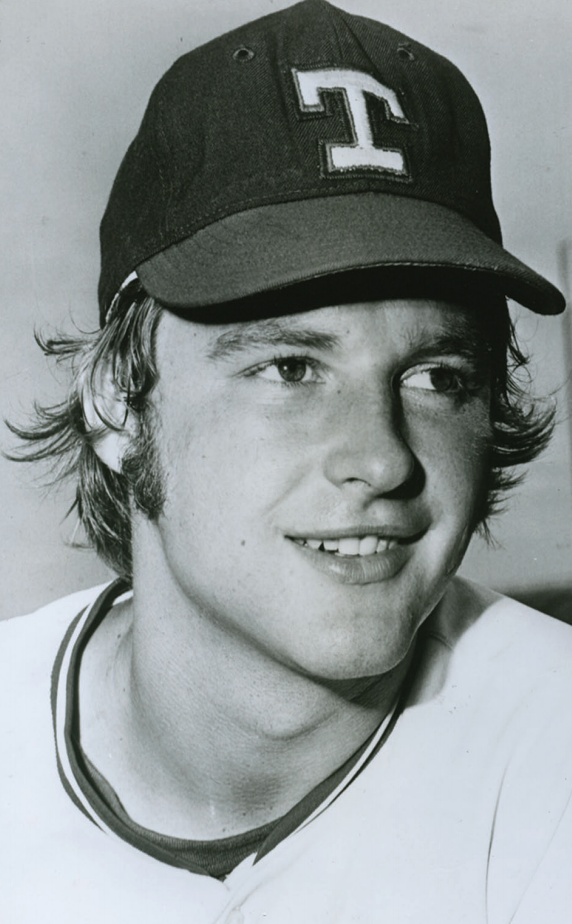

Rich Hand

Rich Hand showed a lot of promise early in his career, but he damaged his own prospects with bitterness every time he felt slighted, and that, along with arm injuries, caused his pitching career to be over by the time he was 26.

Rich Hand showed a lot of promise early in his career, but he damaged his own prospects with bitterness every time he felt slighted, and that, along with arm injuries, caused his pitching career to be over by the time he was 26.

Richard Allen Hand was born on July 10, 1948, in Bellevue, Washington. He was the third of four sons of Betty (née Morse) and Leo Hand, a plumber. Always athletic, Hand dreamed of a career as a professional basketball player, although he also played baseball at Lincoln High School in Seattle. He was good enough at baseball to be selected by the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 38th round of the 1966 amateur draft, but didn’t sign. “I wasn’t physically prepared to play professional baseball,” he later said.1

He chose instead to go to the University of Puget Sound, which offered him a scholarship for both baseball and basketball. While there he realized that baseball was the sport that would give him better opportunities. In the summers of 1967 and 1968 Hand went to Alaska to pitch for the semipro Alaska Goldpanners, winning state championships both seasons. In 1967 they finished tied for fourth at the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas. Back in college, the New York Mets drafted him in the fifth round of the secondary draft in 1968, but again he didn’t sign. “They insulted my intelligence with their offer,” he said.2

Things got even better in 1969. Hand threw a no-hitter against Western Washington and a one-hitter against Washington State, and was named an All-American. In his three seasons in college, he was 21-6 with 216 strikeouts in 215 innings. In June he was drafted first overall in the secondary draft by the Cleveland Indians.

Drafted on June 6, 1969, Hand was quickly signed by Indians scout Loyd Christopher for a bonus of $17,000. “Christopher didn’t offer me the world – but he offered me a chance and that’s what I wanted most.”3 After signing the contract on June 14, Hand was assigned to the Triple-A Portland Beavers, and made his professional debut on June 15, giving up two runs in 1⅔ innings in relief. It took until July 15 before he got his first win, giving up one run in eight innings to beat Spokane. He then got going, winning four more in a row. He finished the season 7-4 with a 3.60 ERA.

In November of that year Hand married Stephanie French, but it didn’t work out and they divorced in early 1972. Also that winter he continued his studies by correspondence, continuing through the spring and summer of 1970 when he gained enough credits to complete his political-science degree.

Hand’s performance at Triple A in 1969 got him a spring training invitation for 1970, but he was a longshot, listed as one of eight pitchers for three open spots in the Indians’ rotation. He believed in himself though: “I believe I have as good a chance as anyone to make this team. I’ve made every team I’ve tried out for.”4

Talking about Hand and fellow pitcher Ed Farmer, manager Alvin Dark said “Each will have to make it as a starter or go back to the minors. Both have got to pitch regularly in order to develop as they should.”5 Hand was almost immediately slowed by a sore back, hurt while swinging a bat, but he soon showed his athleticism by running three miles in 21 minutes, just the second pitcher in camp to do that during the spring.

Just before camp broke, Dark announced the biggest surprise of spring training, naming Hand the third starter. “I’ve seen all I need to see. The kid has done everything we could possibly ask him to do and I’m convinced he can help us as a starter or a long reliever. Any experience he needs, he can get up here with us.”6

Hand made his major-league debut on April 9, 1970, against Baltimore, taking the loss as he gave up six runs in 3⅓ innings. Switched back and forth between the rotation and bullpen, he made 25 starts and 10 relief appearances during the season. He got his first save on May 3, but had to wait until June 7 for his first win. On July 16 he got his first shutout, throwing a four-hitter to beat the Kansas City Royals, 6-0, while allowing just one runner to reach second base. On August 28 he one-hit the California Angels, with the only hit a home run to the second batter of the game, Roger Repoz.

Hand completed the 1970 season with a 6-13 record but a 3.83 ERA, leading him to be considered a good prospect for the future. Indians ace Sam McDowell, talking about the team’s prospects for the coming season, said, “Rich Hand will be our third starter and I know he’s going to be a lot better. Remember, he was just a rookie last summer.”7

The following spring, Hand set lofty goals for himself, saying that in 1971 his goal was “either 20 victories, 20 saves, or a combination of victories and saves equaling 20, depending upon how I’m used.”8 Hand failed at reaching that goal, not just in 1971, but for the rest of his career.

He was slowed in spring training by a muscle strain in his forearm, which put him on the disabled list to start the season. Once he came off he struggled, and with a 1-4 record and 4.65 ERA he was sent to Triple A in early July to get more consistent work in.

That worked out well for Hand as on August 19 he threw a no-hitter against the Tulsa Oilers. He had three walks (all to the same batter) and one error behind him, but noted that he had several instances where fielders made good plays. “This is a big thrill for me, but I had a lot of help. Naturally, I’d have preferred this in the American League,” Hand said. He also said he was aware all the way of the no-hitter: “The guys on the bench were extra quiet and I tried to get them to talk it up a bit.”9

Tulsa manager Warren Spahn said, “He pitched a good game, and it looks to me as if he’s a little too good for this classification,” while Wichita manager Ken Aspromonte said, “This is the happiest moment in my four years of managing.” His pitching coach, Clay Bryant, said, “He’s an intelligent boy. He knows what he has to do and has done it by himself. He deserves the credit.”10

Hand got a dig in at his major-league manager, saying he had been disappointed when Dark sent him to the minors. “I came here determined to prove Dark wrong, but he’s gone now,” referring to Dark’s firing at the end of July.11 Hand still had to wait until the end of the Wichita season – where he had gone 8-2 with a 1.88 ERA – before being recalled to Cleveland. “They just left me there to rot,” he later said. By the time he was recalled, “I had thrown so much that I was really physically depleted. I didn’t do too well, and that made me mad.”12

Hand pitched in five games (four starts) in September, but an ERA of 8.10 brought his season record to 2-6, 5.79. He was disappointed and so were the Indians, who traded him to the Texas Rangers in December. Going to Texas with Hand were Roy Foster, Mike Paul, and Ken Suarez, while in return the Indians got Gary Jones, Terry Lee, Denny Riddleberger, and Del Unser. The trade was characterized as primarily Foster for Unser, although the Rangers said they had held out until Hand was included in the deal.13

“I was real surprised about being traded and, at first, had some mixed emotions about it,” Hand said. “But now I feel it’s the greatest thing that ever happened in my baseball career.” He looked forward to playing for Rangers manager Ted Williams, feeling that Williams must have confidence in him to trade for him. “I feel I’ve had the confidence in myself and my ability, but other people haven’t had that confidence, or at least enough to give me every start and leave me alone when I get in there.”14

Early in his career Hand was a fastball pitcher, but with his arm problems in 1971 he had to change. “After I had my arm trouble, I knew I couldn’t overpower people. I had to work on my control, on just getting the ball over, in order to get people out. So I came up with better control than I had ever had and even after my arm came back, I still had it.”15 He later claimed that the changeup was his most effective pitch, and it helped his fastball too. “With the changeup, the hitter has something else to worry about,” he said.16

After an average spring in 1972, Hand was disappointed once more to be sent to the Rangers’ Triple-A team, the Denver Bears. “Nothing in baseball ever has surprised me more,” he said. “Bitter? yes, I think that’s a fair appraisal. I didn’t have a great spring, I know that, but then who did on our staff?”17

He got two starts in Denver (1-1, 3.46) before being recalled at the beginning of May when Don Stanhouse went on the disabled list. Apart from two relief appearances in late May, Hand spent the whole season in the rotation. He pitched well, ending with a 3.32 ERA, although his 10-14 record showed more about the terrible team he was on, which he led in wins. In fact, the Rangers did not score a single run in support of him during the first 23⅓ innings Hand was on the mound. Talking about that run support toward the end of the season, Williams said, “Look at Hand. He could be a 15-game winner right now with no effort at all.”18

Although respectful of Williams, Hand was not intimidated by him. When Williams once told him, “I hate pitchers,” Hand replied, “‘Ted, I’ve heard that all year, and I’ve never met a manager I liked.’ He thought that was hilarious.”19

Hand admitted that he had trouble when he first came back up to the major leagues. “When I returned, I went out there pitching scared. I was worried about doing good and staying up here.” But he changed his attitude, and that’s when success returned. “I just said to hell with it. … I just started pitching … reaching back, letting it fly and putting things out of my mind, like going back to Denver.”20

During 1972, things changed for Hand personally, too. His first marriage ended at the start of the year, and in September he married Terrie Molnar, a schoolteacher he had met while in Cleveland. Several of his teammates and their wives attended, including Mike Paul, with whom he’d been traded from Cleveland, as best man. Over the next few years the couple had a son and a daughter together.

The 1973 season started slowly for Hand; he was 2-3 with a 5.40 ERA on May 20. On that day he was traded to the California Angels, along with first baseman Mike Epstein and catcher Rick Stelmaszek, for first baseman Jim Spencer and pitcher Lloyd Allen. Once again Hand was upset with being traded. “I couldn’t have been happier where I was. It’s not the greatest team right now, but it’s headed in the right direction. I wanted to grow with this team and I hate to leave Arlington. That’s a fine place to live.”21

Used by the Angels mostly as a long reliever, Hand pitched decently, although he spent more time on the disabled list with arm problems. He returned, though, and in four starts at the end of the season he was 2-1 with a 2.77 ERA. On September 26 Hand started and had a 4-3 lead after seven innings. Going out for the eighth, he pitched to one batter, Jeff Burroughs, who homered to tie the game. That ended up being Hand’s final batter faced in the major leagues.

His performance in September led to the thought that he might make the rotation in 1974, but once again, at the end of spring training Hand was sent to Triple-A Salt Lake City. He considered not reporting, but did, and struggled through the season with Salt Lake, also spending the last couple of months on option to Pawtucket in the Boston Red Sox farm system.

After a forgettable season, in October Hand was sent to the St. Louis Cardinals organization as the player to be named later, completing a September deal which had brought Orlando Pena to the Angels.

As 1975 arrived, Hand decided he had had enough of baseball. His arm hurt and he was tired of the minor leagues. He decided not to report to the Cardinals, and although there were teams interested in him – Oakland reportedly offered him a contract – he chose instead to retire from baseball. “I probably exited the game too soon, but I had a lot of pain. … I still had some years left.”22

Home, now, was Arlington, Texas, which Hand had called a fine place to live when he was traded from the Rangers to the Angels in 1973. As of 2018 Hand had made the Dallas-Fort Worth area his home since he retired from playing.

Hand had begun working in business while still playing baseball, and now his efforts expanded. He became involved in real estate, owning construction companies, and partnering in real-estate ventures around North Texas, and as a managing director in an asset-management company.

His marriage to Terrie had ended, and in 1987 he married Susan Hardin. Over the next decade the couple had four daughters, all of whom were athletically successful. With Hand involved as a parent and coach, the children performed on select basketball teams, won various championships across the country, and all went to college on basketball scholarships. His daughter Whitney was a star player at Oklahoma and was drafted by the WNBA, but decided not to go pro because of several knee injuries. She married Oklahoma quarterback Landry Jones, who went on to play in the NFL with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

As of 2018 Hand remained involved with baseball. He has been a board member of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association for many years, and appeared several times a year at Rangers functions on behalf of the team.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Steve West in completing this article.

Notes

1 Russell Schneider, “Dark Counts on Right Hand for No. 3 Hill Job,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1970: 23.

2 Ibid. Players who had previously been drafted but not signed were not eligible for the regular phase of future drafts. Instead they were included in a secondary phase, which took place after the regular draft. This system lasted through 1986, when all players were consolidated into a single draft.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Russell Schneider, “Indians Turn ‘Camp Cheerful’ Into “Iwo Jima’ for Pitchers,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1970: 20.

6 Russell Schneider, “Dark Counts.”

7 Russell Schneider, “Mound Award Excites and Delights Sudden Sam,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1970: 58.

8 Russell Schneider, “Brown Trying Sims’ System on Dark,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1971: 37.

9 John Ferguson, “AA’s Second No-Hitter: Hand Chokes Off Tulsa,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1971: 35.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Randy Galloway, “Young Hurler Hand Rated Rangers’ Prize Catch,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1971: 38.

13 Merle Heryford, “Rangers Size Up Foster as Home-Run Threat,” The Sporting News, December 18, 1971: 47.

14 Randy Galloway, “Young Hurler Hand.”

15 Ibid.

16 Randy Galloway, “Ranger Rich Gets His Men with Tight-Hand Policy,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1972: 18.

17 Ibid.

18 Merle Heryford, “Rangers Lasso Wins with Castoff Hurlers,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1972: 21.

19 Dan Raley, “Where Are They Now: Rich Hand, Former Lincoln High, UPS Standout,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, seattlepi.com/sports/baseball/article/Where-Are-They-Now-Rich-Hand-fomer-Lincoln-1247298.php#photo-677682, retrieved January 31, 2018.

20 Randy Galloway, “Ranger Rich.”

21 Randy Galloway, “Epstein Knapsack Full of Kind Feelings,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1973: 20.

22 Dan Raley, “Where Are They Now.”

Full Name

Richard Allen Hand

Born

July 10, 1948 at Bellevue, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.