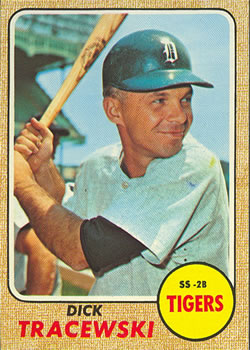

Dick Tracewski

Richard Joseph “Trixie” Tracewski was an average-hitting, good-fielding shortstop whose career in baseball spanned both the National and American Leagues, four World Series rings, and a Detroit Tigers record span as both a base and bench coach. Also known as “Dick Tracy” by many fans in Los Angeles during his four years with the Dodgers (1962–1965), he played shortstop, second base, and third base in his eight years as a player, retiring with a fielding percentage of .961. In a career distinguished by professionalism and respect from virtually everyone he encountered from umpires to managers, Tracewski was a witness to and participant in baseball history.

Richard Joseph “Trixie” Tracewski was an average-hitting, good-fielding shortstop whose career in baseball spanned both the National and American Leagues, four World Series rings, and a Detroit Tigers record span as both a base and bench coach. Also known as “Dick Tracy” by many fans in Los Angeles during his four years with the Dodgers (1962–1965), he played shortstop, second base, and third base in his eight years as a player, retiring with a fielding percentage of .961. In a career distinguished by professionalism and respect from virtually everyone he encountered from umpires to managers, Tracewski was a witness to and participant in baseball history.

Tracewski was not only multitalented as a player, but after being promoted from the minors to his first coaching position with the Tigers in 1972, took on a range of coaching roles under multiple managers and general managers. Beloved and remembered by fans in Detroit for his ever-steady presence at both the first- and third-base coaching boxes, he found his career extended and expanded under Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson, who invited him to remain with the team in 1980 and gave him additional responsibilities. This included mentoring a new generation of ballplayers such as Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker, as well as two brief stints as Detroit manager in 1979 and 1989, the latter occurring when Anderson took a leave of absence.

A member of two Dodgers championship teams, 1963 (his rookie year) and 1965, as well as part of the Tigers’ 1968 World Series winner, Tracewski played or worked for three of baseball’s leading minds in Walter Alston, Billy Martin, and Anderson. Although perhaps better known for his coaching career, as a rookie he scored the eventual winning run in the opener of the Dodgers-Yankees World Series. Tigers manager Mayo Smith also credited him for helping to turn around the 1968 season with a game winning three-run home run against Cleveland June 23 that spurred a winning streak.

Tracewski was born February 3, 1935, in Eynon, Pennsylvania, a small town in the northeastern part of the state, as the youngest of four children. He was always an excellent athlete and baseball player, in some ways following in the footsteps of his older brother, a minor leaguer in the Philadelphia Athletics system who also played professional football. Tracewski’s parents were Polish immigrants who instilled in him a work ethic that was reflected in his baseball career—his father having arrived in the United States at age 16 and then returning to Europe at 18 to fight for his newly adopted country in World War I.

Tracewski established himself a rising star during his teen years and in high school, playing for Archibald High and leading teams in the highly popular and competitive sandlot games that took place on Sundays, as well as with American Legion teams. He attracted the attention of major league scouts, including Ray Welsh of the Pittsburgh Pirates, who advised Tracewski, then a high school sophomore, to focus on shortstop. As he approached age 17 and awaited signing offers from the many scouts he had come to know, Tracewski was surprised to find that no offers were forthcoming. This was particularly true of the Cleveland Indians, who had previously indicated a serious interest in the young infielder.

As Tracewski related in a 2007 interview, this was when fortune smiled upon him. Brooklyn Dodgers scout Phil Weinnert got lost on the way back from Binghamton, New York, to his Philadelphia home. He came across a local baseball game in Jessup, Pennsylvania, which featured the Peckville VFW team and wound up watching the entire game. As was frequently the case, Tracewski stood out, and after the game Weinnert approached him to ask when he might see another game. After several failed efforts, Weinnert returned personally and invited Tracewski to come (with his father) to Brooklyn for a workout. He thus found himself, at 17, at Ebbets Field, spending four days hitting and fielding with Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, and Gil Hodges.

Shortly thereafter, the Dodgers signed him as an amateur free agent in 1953 and he launched what was to be a long career, along with a signing bonus of several hundred dollars. He was quickly sent to Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Florida, where he began a six-year career in the minors which saw him crisscross the country, playing at every level in the team’s farm system. Tracewski also performed two years’ military service during this period, posted with other baseball players at Fort McPherson, Georgia, outside Atlanta. It was during this period where he had his greatest regret as a pro ballplayer. Given the option to develop skills as a switch-hitter, he chose not to. When he finally arrived in the major leagues he realized what a mistake this was as “I had to face pitchers like Bob Gibson and Juan Marichal who were so nasty against right-handers.”

Tracewski was called up to the Dodgers from their AAA Omaha farm team in 1962, beginning his 42-year big- league career with a debut as a pinch-runner in the final game of the first-ever series at the new Dodger Stadium. Although he was never to experience a losing season as a player, Tracewski still remembers that first year painfully, as the Dodgers lost a two-game lead at the end of the season courtesy of three straight defeats to St. Louis. This was followed by a playoff loss to the San Francisco Giants in only the fourth-ever such series in major league history. That Dodgers team grew stronger from the experience, however, and behind the pitching of Tracewski’s friend, Sandy Koufax, would win the first of two World Series with Trixie as a utility infielder.

It was in the 1963 World Series that Tracewski would experience what he considers his greatest moment as a professional baseball player. In his first-ever postseason at bat, Tracewski singled off future Hall of Famer Whitey Ford and scored what proved to be the winning run on a John Roseboro home run. With Koufax pitching a 2–1 victory, the Dodgers proceeded to sweep the Yankees. Although many still remember him for a key diving stop in Game 4 of the Series, Tracewski still remembers that first World Series hit with fondness and emotion. He was also on the field during the notorious moment in the August 22, 1965, game when Roseboro was struck in the head with a bat swung by Juan Marichal, a strong memory for him even today. It was as a Dodger that Tracewski was nicknamed Trixie, a sobriquet that sticks to this day. During summer pool parties hosted by reliever Ron Perranoski, Tracewski could frequently be found performing back flips, front flips and other tricks and was thus dubbed Trixie by his teammates.

Tracewski played in three of Koufax’s four no-hitters (going 3 for 7 at the plate) and also was part of the 1965 world champion team before being traded to the Tigers for pitcher Phil Regan on December 15, 1965. This proved to be the start of a new phase of his career—one which initially frustrated him, as his playing time was already dwindling and he could see the end approaching. Tracewski even went so far as to approach Tigers General Manager Jim Campbell shortly after arriving in Detroit with a request to be traded. He argued that since he’d arrived it was clear his playing time would be limited and asked that Campbell move him where he’d have a chance to extend his career. After considering the request briefly, Campbell refused, asking Tracewski to be patient. Although he indeed became more of a spot player for the team, Tracewski quickly established himself as an important part of the Tigers with his fielding skills, ability to cover multiple positions, work ethic, and knack for clutch hitting. During 1968 he played in 90 games for the Tigers, hitting four home runs, including the three-run shot against Cleveland in the nightcap of a June 23 doubleheader, the opening salvo in a 4–1 Detroit win that Mayo Smith credited with spurring on the team in its pennant run.

It was shortly after the 1969 season that Campbell offered Tracewski a coaching position with the Tigers, which Trixie enthusiastically accepted as a golden opportunity to extend his professional career. He quickly established himself as an excellent coach and mentor to young athletes, leading second-year Tigers manager Billy Martin to promote him from the minors and make him first-base coach. Success followed Tracewski to his new coaching position, as the 1972 team won the American League East. Martin, however, would only last another season, canned after famously ordering his pitchers to throw spitballs. It was during Martin’s tenure that Tracewski, generally known as among the nicest men in the game, experienced his only ejection, an incident Martin found highly amusing. The ejection aside, Tracewski established a strong rapport with umpires throughout the major leagues, a relationship of mutual respect and even friendship. This was perhaps strengthened by the fact that Hall of Fame umpire Nestor Chylak was a longtime neighbor of his in Peckville, Pennsylvania.

Tracewski’s baseball knowledge and teaching abilities would play a significant role in the Tigers’ restructuring efforts, which began with the hiring of Ralph Houk for the 1974 season. Although the next few years saw many losses, they also witnessed the signing of a new generation of Detroit heroes, a group that began to pay dividends in 1978 when the team finished 86–76. In one year alone, the team added Alan Trammell, Lou Whitaker, Jack Morris, and Dan Petry—all instrumental parts of the Tigers’ future success. Tracewski remains particularly proud of his work with Trammell, the shortstop he worked with closely as a young ballplayer and watched grow into one of the game’s best. Even more than a decade after Trammell’s retirement as a player, Tracewski believed strongly that Trammell should be in the Hall of Fame. Tracewski expressed his frustration at the lack of recognition for his student, stating, “There is no justice in baseball” when Ozzie Smith—a great player in his own right whose career paralleled Trammell’s—receives more than 300 votes for the Hall while Trammell collected barely 70.

He was named manager for two games in 1979—winning both—pending the arrival of Sparky Anderson, the man Tracewski worked with for virtually the rest of his career. He continued as base coach and mentor for the Tigers, a perennial AL power for much of the 1980s. He also served as bench coach and right-hand man to Anderson, whom he considers among the greatest managers of all time. Tracewski credits Anderson for reinforcing the importance of always giving 100 percent—from spring training to the final out—and also cites his ability to understand and communicate with modern-day players. Working closely, Anderson established plans for every aspect of the game and every player, communicating on a daily basis with those like David Wells, who thrived under such a method—and never with others who were best left alone. Although Anderson was known by some as Captain Hook, Tracewski points out that he only lived up to that moniker when he had a strong bullpen.

Tracewski managed the Tigers again for three weeks during 1989 while Anderson recovered from exhaustion. This was a bittersweet time as he watched his close friend approach the end of his managing career—and the Tigers go from league power to a team that lost more than 100 games. He retired after the 1995 season. He returned to northeastern Pennsylvania, having moved his family there after being traded to the Tigers from the Dodgers three decades earlier.

During a career spanning several decades of baseball history, Tracewski played in virtually every major league ballpark and watched the game change in myriad ways. When Tracewski entered the majors he received a base salary of $7,200, an amount he quickly doubled through a then-record payout of $14,500 to members of the world champion Dodgers. As he recalls it, the manager’s authority was unquestioned during that period and players used spring training to get fit for the regular season. Players during his coaching years were more independent and generally arrived fit for spring games. They also enjoyed considerably more job security and were able to focus almost entirely on baseball. Like most of his counterparts, Tracewski always worked during the off-season; the added job security, he asserted, became one of the biggest changes he witnessed in the game. A close second would be the fact that players are now bigger, stronger, and faster. As Tracewski posited, those who reminisce about the good old days perhaps do not realize how much the game has changed. Among other things, Tracewski also believes modern equipment has degraded, noting in particular the low quality of wood used in bats which now shatter with a frequency unheard of during his playing days.

Indicative of the strong friendships and relationships he had in the game, as well as his unique perspective, Tracewski cited the top five players he saw:

- Sandy Koufax—Tracewski’s friend to this day and roommate with the Dodgers who performed “feats which will never be duplicated.”

- Maury Wills—a man who changed the game, bringing back the days of Ty Cobb with his 100 steals a season.

- Al Kaline—the best all-around field player he’d ever seen and a precursor to today’s five-tool player.

- Dick McAuliffe—his Tigers teammate and a three-time All-Star at second base during the 1960s.

- Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker—the shortstop-second base combination that epitomized Tigers teams of the 1980s.

Tracewski considers himself lucky in many ways to have played or worked for some of the greatest baseball minds around. This includes the late Walter Alston who managed him with the Dodgers and was a close second to Sparky Anderson, as the manager Tracewski respected most. He fondly remembers breaking in as a coach under Billy Martin, whose innovations and fire led the younger Tracewski to believe Martin had invented the game. Tracewski also feels blessed to have worked with Ralph Houk on the successful rebuilding project that GM Jim Campbell oversaw with the mid-1970s Tigers.

In retirement, Tracewski has participated regularly in Tigers fantasy camps, gone to spring training, and maintained contact with current and former Tigers like Alan Trammell. Since retiring from baseball in 1995, Tracewski has continued to be active, playing golf with his friend Sandy Koufax, and at least one trip a year to Detroit. He recently had the opportunity to tour old Tiger Stadium, marveling at the shape of the grass field as his grandson ran the bases on what he considers one of the great ballparks in which to play or watch a game. Tracewski also had one last trip to Vero Beach planned, as the Dodgers prepare to close down Dodgertown and move to Arizona after the 2008 exhibition season, as Tracewski longed for another chance to walk the fields and basepaths where his remarkable four-decade pro career began.

Sources

“No. 43—Dick Tracewski—Eynon.” The Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pa.), November 15, 2004.

McAuliffe, Josh, “Son of immigrant coal miner finds himself on the field with Jackie Robinson,” March 11, 2007.

McAuliffe, Josh, “Lion in Winter: A League of His Own, Richard ‘Dick’ Tracewski” March 11, 2007.

http://www.baseball-reference.com (Dick Tracewski entry)

http://www.wikipedia.com (Dick Tracewski entry)

Levine, Peter M. Richard Tracewski telephone interview, June 1, 2007.

Full Name

Richard Joseph Tracewski

Born

February 3, 1935 at Eynon, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.